The Domesday Book

The Domesday Book was commissioned in December of 1085 by William the Conqueror. The first draft was complete by August, 1086 and held records for 13,418 towns and villages of England. The Domesday survey covered all of England as it existed in 1086, including parts of Cumbria and Wales, but excluding present day Northumbria.

Major cities, like London itself and Winchester, were excluded.

This book is an extensive record of landholders, tenants, and serfs. The acreages of farmland, woodland, and meadow; fish, plows on the land, any buildings, castles, churches, salthouses or mills were recorded. It wasn't a census. It was intended to be a complete survey of taxable assets.

During the final years of the reign of William the Conqueror, he was running out of money. The greatest threat to his reign came from the North--King Canute IV of Denmark and King Olaf III of Norway both threatened to invade England, and were bought off by paying huge bribes, called Danegeld. William paid; it was the price of keeping peace in his realm while he unified England.

The king sent out his royal commissioners to complete this survey. They were thorough . One observer wrote:

"There was no single hide nor yard of land, nor indeed one ox nor one cow nor one pig which was left out."

The grand and comprehensive scale of this survey, and the irrevocable record it produced, led people to compare it to Doomsday, as in the Bible, when a person's deeds are written in the Book of Life and put before God for the Final Judgement. This name was given to the survey in the late 12th century, and at that time in England, "Doomsday" was spelled "Domesday". I have seen in print references to this book as "The Doomsday Book", but the English convention is to spell it "The Domesday Book".

From "The Ely Inquest", a 1086 publication:

"...they (the Royal Commissioners) inquired what the manor was called; who held it at the time of King Edward; who holds it now; how many hides there are; how many ploughs in demesne (or, held by the lord of the manor), and how many belonging to the men; how many villagers; how many cottagers; how many slaves; how many freemen; how many sokemen (farmers who had tenure and paid a fixed rent of either labor, money or goods annually to the lord of the manor); how much woodland; how much meadow; how much pasture; how many mills; how many fisheries; how much had been added to or taken away from the estate; what it used to be worth altogether, and what it was worth now;how much each freeman and sokeman has.

All this to be recorded thrice, namely, as it was in the time of Kind Edward, as it was when King William gave it, and as it is now. And it was also to be noted whether more could be taken than is now taken (in taxes)."

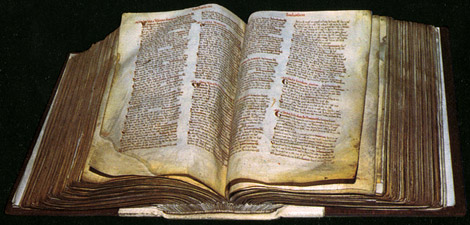

This mass of data was written in Latin. It was compiled in Latin--it was sorted into counties, landholders, and manors.

The main volume, the Great Domesday, is written on sheep-skin parchment using black and red ink. It was compiled by a sole scribe. William the Conqueror died before the scribe could complete the compilation, so the uncompiled remainder is the Little Domesday. The three counties in the uncompiled Little Domesday are Essex, Norfolk, and Suffolk, and the Little Domesday book is 475 pages. The Great Domesday, covering all the rest of medieval England, is 413 pages, so we can see how much detail was left out in compiling.

It's a fascinating piece of history, so rich in detail. It gives us a wonderfully specific picture of life in medieval England.

This book was used in courts of law for a century after its creation to determine a person's status--whether free or serf. It was the consulted authority to determine the landholdings of the aristocracy for many, many years.

And now it's a sparkling gem in the crown of recorded history.