Women's Roles in Early Modern England

In English Society: 1580-1680, Keith Wrightson questions the use of gentry-centered sources traditionally relied upon in the reconstruction of early modern English history, suggesting that middle class diaries, court records, and other evidence left by the poor and “middling sort” of people provide a broader and more inclusive picture of the times. This picture includes a view of gender relations as less authoritarian and patriarchal than one might assume based on the reading of conduct books suggesting that a wife was “wholly to depend upon [her husband], both in judgment and in will.” Instead, Wrightson’s study of middle class diaries indicates the existence of regular household quarrels, which generally ended not with the assertion of absolute masculine authority, but with the gradual development of understanding between husband and wife. However, friendly spousal relations do not by any means disprove a trend of widespread misogyny during the period. Barry Reay’s Popular Cultures in England: 1550-1750 and Carol Z. Wiener’s study of “Sex Roles and Crime in Late Elizabethan Hertfordshire” assert that traditional gender roles were to a large extent upheld in early modern England, assisted by a common conception of man as naturally dominant and superior and by the common practice of shaming rituals, which both Eamon Duffy and Mark Kishlansky link to the rise of English Protestantism.

Although Wrightson’s analysis of early modern gender relations emphasizes the companionate nature of spousal interactions, which he insists “often overshadow[ed] theoretical adherence to the doctrine of male authority and public female subordination,” it is difficult to disregard that doctrine as entirely insignificant, when the seemingly unanimous opinion of contemporary conduct books held that that “The whole duty of the wife is referred to two heads. The first is, to acknowledge her inferiority: the next, to carry her selfe as inferior,” a staggeringly misogynistic statement in the eyes of a modern reader. Additionally, this conception of female submissiveness and male dominance, or even abuse, seems consistent with early modern sexual vocabulary as described by Reay, which frequently described courtship as siege and intercourse as conquest, or any number of similarly violent terms, such as “banging,” “beating,” “piercing,” or “punching.”

Even if affectionate partnerships were the norm within private homes, with both wife beating and wifely scolding subject to public sanction, it seems rather telling of a public climate of general misogyny that mere scolding from a woman was considered a serious crime, similar to a violent outburst from a man. The early modern world even had forms of corporal punishment specifically designed to silence scolding women, including the cucking or ducking stool and the branks or scold’s bridle. The former was a stool onto which a woman could be strapped in place for a public shaming and possibly submerged in cold water, while the latter, in perhaps the most graphic gesture of silencing, was a bridle which included a metal spike intended to depress the tongue of a “common shrew.” According to Eamon Duffy, cucking stools became more prominent in southwestern towns in the late sixteenth century, perhaps as a result of the diminished status of women after the Reformation did away with the veneration of female saints like the Virgin Mary and the locally popular St. Sidwell. This is a view consistent with Christopher Haigh’s observation that Protestantism was not popular among women, who constituted less than one fifth of Marian martyrs, and with Mark Kishlansky’s suggestion that the rise of Puritanism enhanced the success and popularity of shaming rituals.

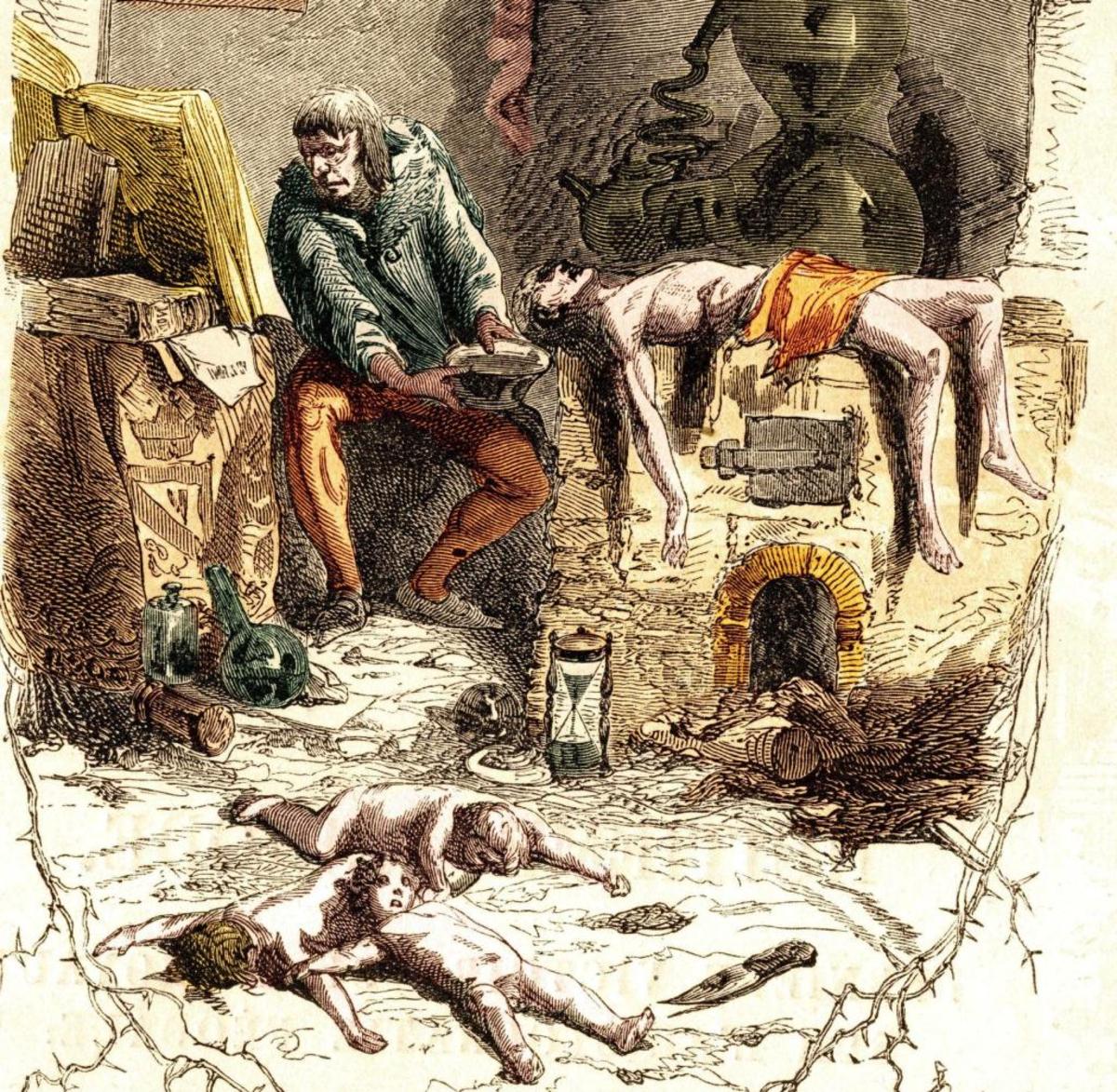

Although one shaming ritual, known as charivari, eventually evolved into a punishment for wife-beaters in the 1800s, its victims originally largely consisted of cuckolds and dominant or adulterous women, placed in the same category as physically abusive spouses for flouting the authority of their husbands. Better known as skimmington or riding the stag depending on the location, charivari was a ritual that involved parading its victims (or effigies of victims) before a crowd on a pole or backwards on a horse to the tune of cacophonous music played on pans, bells, and horns, which may be taken to symbolize cuckoldry. Occasionally, these rituals went further than humiliation, ending in violent beatings, particularly for the uncooperative.

As Reay states, it seems that shaming rituals “enforced a highly gendered morality,” punishing those who stepped outside of traditional gender roles. These shaming rituals, along with general societal expectations and misogynistic discourse, seem to have been largely successful in achieving their goals. Although Reay uses examples of strong and rebellious women in contemporary literature to suggest that women may have defied male authority with some degree of frequency, it should be remembered that literature is not always an accurate reflection of reality. As Carol Z. Wiener points out in her introduction to “Sex Roles and Crime in Late Elizabethan Hertfordshire,” conduct books indicated how people should behave, whereas more raucous ballads depicting women beating drunken husbands may simply reflect a taste for satire. Using crime statistics as an alternate object of analysis, Wiener reveals a very gendered division of crime, with women “less likely [than men] to participate in crimes which demonstrated a high degree of initiative, autonomy, and self-assertion.” According to Wiener’s research, criminal women were most commonly guilty of receiving stolen goods from male thieves, exercising aggression through slander rather than physical violence, and perpetrating “religious offenses or politically motivated riots in which the women, through defying one authority, demonstrated obedience to another authority or set of rules.” This high occurrence of female rioters and the moral justification felt by such rioters is also confirmed by both Wrightson and Reay, making this explanation appear highly plausible.

Although crime statistics are not an accurate representation of the entire population, a lower instance of violent crime amongst women seems to indicate lower levels of publicly demonstrated aggression, and women’s tendency towards offenses grounded in loyalty to religious faith or long-held customary political rights seems to indicate that they felt a strong sense of loyalty to authority, even while defying the law. Therefore, it seems reasonable to draw the conclusion that, while women may have occasionally privately quarreled and reached compromises with their husbands, as suggested by Wrightson, and may have occasionally been portrayed as aggressive in popular literature, as shown by Reay, in the public sphere, they probably largely conformed to societal expectations of passivity and obedience.