- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- Life Sciences»

- Paleontology

Venomous Vestiges

Many of the revelations about the lives of long-dead animals have come to us through sheer luck. We are lucky enough to have found specimens of birds and non-avian dinosaurs with their scales or feathers preserved in stone, let alone intact proteins and pigment cells. So far, however, no evidence of venom or the organs that produce it has yet been uncovered in any prehistoric animal, never mind its makeup or how deadly it was in life. We have, however, discovered enough extinct genera either related or with enough similarities to living venomous animals to infer that this substance has been in use for millions of years.

Here are three particularly noteworthy (though not all promising) cases of potentially venomous animals, along with a few more obscure and less studied species.

NOTE: The terms "poison" and "venom" are often used interchangeably to describe substances that cause extreme harm, sickness, or death when the human body is exposed to them. In biological terms, however, the term "poison" or poisonous" is generally given to animals or plants that are deadly when touched or eaten (i.e. poison ivy, poison dart frog)."Venom" is the name given to the dangerous substances animals inject into predators or prey with fangs, stings, or saliva, and will therefore be the preferred term in this article.

Toxic Dinosaurs?

In both the book and the film adaptation of Jurassic Park, Dilophosaurus is depicted as venomous, blinding and immobilizing its victims with volleys of tar-like liquid before ripping them to pieces. Compsognathus is also depicted as mildly venomous in the book, and (spoiler alert) a swarm of them eventually kill the park's creator, John Hammond. No scientific examination of these two Jurassic theropods, however, has lent any proof that either of them possessed glands for projecting or injecting venom.

Yet the idea of venomous dinosaurs is not limited to Jurassic Park. The 1977 book The World of Dinosaurs suggested that Iguanodon used its enlarged thumb spike to poison potential predators or rivals. However, this feature lacked a chamber for housing venom or grooves to administer it, and an Iguanodon would not have been able to use it as a weapon without getting close enough for its opponent to bite or slash it (or, if a rival Iguanodon, to inject its venom first).

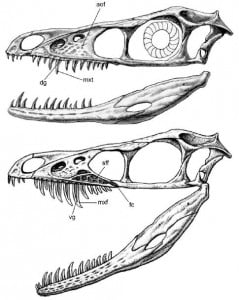

A much more serious contender for a being venomous dinosaur comes in the form of Sinornithosaurus, a gliding, arboreal dromaeosaur from Early Cretaceous China. Known from fossils that preserved prominent feathers as well as pigment cells, one specimen was found with unusually long, grooved teeth resembling those of a modern gila monster and what appeared to be venom glands in its upper jaw. Based on these features, a team of American and Chinese scientists concluded in 2009 that Sinornithosaurus was the first bona fide venomous dinosaur, immobilizing its victims with its venom-dripping fangs before feasting on them.

The following year, these findings were disputed by a trio of Argentine paleontologists, who pointed out that none of these features suggested this dinosaur was venomous. The teeth, they pointed out, had been loosened from their sockets, making the animal's fangs appear longer than they actually were. They also pointed out that the grooves running along Sinornithosaurus' teeth resembled those of other, non-venomous theropods more than vipers and other animals that administer the substance through these structures. As for the supposed venom sacs, these were too were dismissed as being little different from those found in the upper jaws of other theropods. Though it was still depicted as venomous in the 2011 BBC program Planet Dinosaur, this skeptical point of view seems to have won out and become more widely accepted than the notion of a venomous Sinornithosaurus.

Just because no dinosaurs have been confirmed to be venomous, however, doesn't rule out the possibility that some used harmful chemical substances for hunting or defense. A few modern birds have been known to coat their skin or feathers in venom from the insects and plants they prey upon, thus protecting them from predators. Considering that birds evolved from carnivorous dinosaurs, this behavior may well have began with their theropod ancestors.

Venomous Varmint

Five million years after the extinction of the dinosaurs, what appears to be the first known venomous mammal inhabited modern Alberta. Though known to scientists for many decades, it wasn't until the mid-2000s that the canine teeth of the mouse-sized Paleocene mammal Bisonalveus were discovered. Measuring less than a quarter of an inch, these teeth were grooved and, because there are no corresponding teeth in the animal's lower jaw, are thought to have injected venom that served to paralyze the insects it fed upon. The lower canines of a more modern venomous mammal, the shrew-like solenodon from the Caribbean, serve a similar purpose.

Only a handful of modern mammals (most famously, the duck-billed platypus) are known to utilize venom. Bisonalveus, a member of the extinct cimolestids, was unrelated to any them, leaving open the question of how venom evolved in these select species.

The Venom Lizard King

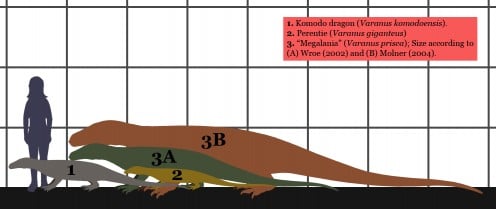

Reaching a maximum size of ten feet long and about three hundred pounds, the Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis) of Indonesia is not only the largest lizard alive today, but the largest venomous animal on land.

As recently as 42,000 years ago, however, this was not the case: During the late Pleistocene, the largest predator to inhabit the Australian mainland was Varanus priscus, better known as Megalania (its original name; its placement into the genus Varanus is somewhat disputed). Measuring between about fifteen to twenty-five feet and weighing between 700 and 1,400 pounds (depending on which estimates you consult), it is known to be the largest lizard ever to have existed. In addition, if it had venom glands, it would also be the largest venomous vertebrate of all time.

Megalania is known from many incomplete fossils, putting both its size and closest modern relative up for debate. Many of the higher estimates are based on the Lace monitor or the perentie, both monitor lizards native to Australia (or "goannas"), while lower estimates of the animal's size are generally based on the Komodo dragon. As of yet, fossils indicating that this giant was venomous have yet to be found. Every living monitor lizard, however, possesses some sort of venom and some, like the Komodo dragon, draw their venom from their bacteria-ridden saliva, which mixes into their victims' bloodstream with every bite.

But why would such a huge and powerful predator even need venom? Like other reptiles, Megalania is thought to have been ectothermic (or "cold-blooded"), relying on external sources of heat and permitted only short bursts of speed. While modern monitor lizards are capable of accelerating very quickly, this monster's bulk would have relegated it to ambush hunting, as the marsupials and birds (and people) that made up its diet could easily have outpaced the giant reptile. If it had venom glands, however, and managed to even nip one of its victims, the lizard's sheer size would no longer be an obstacle in subduing warm-blooded prey.

Megalania mysteriously vanishes in the fossil record around 40,000 years ago, along with the many of the giant marsupials and birds it likely preyed upon. Despite this, tales abound of giant monitor lizards and mutilated livestock sighted across Australia and New Guinea.

Other (potentially) venomous prehistoric animals

- Conodonts- primitive jawless fish thought to be the oldest known venomous animals, based on grooved, elongated teeth; widespread and successful group that existed from the Late Cambrian to the end of the Permian.

- Pulmonoscorpius- Giant scorpion from Carboniferous Scotland measuring 3 feet long. All modern scorpions possess venomous stings, and those with smaller pincers and thicker tails (of which Pulmonoscorpius was one example) tend to have more fatal venom than those with large pincers and thinner tails.

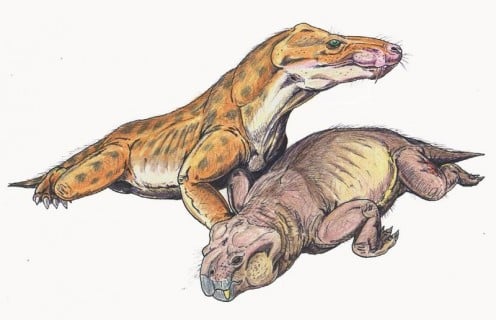

- Euchambersia- therocephalian synapsid ("mammal-like reptile") from Late Permian South Africa with fangs that appear to have been designed for injecting venom.

- Uatchitodon- oldest known venomous sauropsid ("true reptile") and archosaur; known only from hollow, grooved teeth from Triassic rocks in Arizona, North Carolina, and Virginia.

SOURCES

Handwerk, Brian. "Venomous Dinosaur Discovered--Shocked Prey Like Snake?" National Geographic News, 21 Dec 2009

Laden, Greg. "The Origin of the Komodo Dragon." Smithsonian Magazine, 30 September 2011

www.paleocene-mammals.de

www.prehistoric-wildlife.com

Roach, John. "Extinct Mammal Had Venomous Bite, Fossils Suggest." National Geographic News, 22 Jun 2005

Sues, Hans-Dieter. "Sharper Than a Serpent's Tooth." National Geographic, 24 Nov 2010

Switek, Brian. "Sinornithosaurus Probably Wasn't Toxic After All." Smithsonian Magazine, 9 Jul 2010

Switek, Brian. "A Mysterious Thumb." Smithsonian Magazine, 27 Dec 2011

Switek, Brian. "A Dirty, Deadly Bite." wired.com, 14 Aug 2012

Szaniawski, Hubert. "The earliest known venomous animals recognized among conodonts." Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 6 Oct 2009

"Therocephalian and Synapsid Hunters Spanning the Globe." www3.telus.net, 19 May 2007