theories of foreign exchange

theories of foreign exchange

The foreign exchange market is the market in which foreign currency—e.g., the yen or euro or pound—is traded for domestic currency—e.g., the U.S. dollar. It is not in a centralized location and, instead, is a decentralized network that is, nevertheless, highly integrated via modern information and telecommunications technology.

The exchange rate is the price of foreign currency. For example, the exchange rate between the British pound and the U.S. dollar is usually stated in dollars per pound sterling ($/₤); an increase in this exchange rate from, say, $1.80 to say, $1.83, is a depreciation of the dollar. The exchange rate between the Japanese yen and the U.S. dollar is usually stated in yen per dollar (¥/$); an increase in this exchange rate from, say, ¥108 to ¥110 is an appreciation of the dollar. Some countries float their exchange rate, which means that the central bank (the country’s monetary authority) does not buy or sell foreign exchange, and the price is instead determined in the private marketplace. Like other market prices, the exchange rate is determined by supply and demand—in this case, supply of and demand for foreign exchange.

Some countries’ governments, instead of floating, fix their exchange rate, at least for periods of time, which means that the government’s central bank is an active trader in the foreign exchange market. To do so, the central bank buys (or sells) foreign currency depending on which is necessary to peg the currency at a fixed exchange rate with the chosen foreign currency. An increase in foreign exchange reserves will add to the money supply, which could lead to inflation if it is not offset by the monetary authorities via what are called sterilization operations. Sterilization by the central bank means responding to increases in reserves so as to leave the total money supply unchanged. A common way to accomplish it is by selling bonds on the open market; a less-common way is to increase in reserve requirements placed on commercial banks.

Still other countries follow some regime intermediate between pure fixing and pure floating. (Examples include bands or target zones, basket pegs, crawling pegs, and adjustable pegs). Many central banks practice managed floating, whereby they intervene in the foreign exchange market by leaning against the wind. To do so, a central bank sells foreign exchange when the exchange rate is going up, thereby dampening its rise, and buying when it is going down. The motive is to reduce the variability in the exchange rate. Private speculators may do the same thing: such “stabilizing speculation”—buying low with the plan of selling high—is profitable if the speculators correctly anticipate the direction of future exchange rates.

Until the 1970s, exports and imports of merchandise were the most important sources of supply and demand for foreign exchange. Today, financial transactions overwhelmingly dominate. When the exchange rate rises, it is generally because market participants decided to buy assets denominated in that currency in the hope of further appreciation. Economists believe that macroeconomic fundamentals determine exchange rates in the long run. The value of a country’s currency is thought to react positively, for example, to such fundamentals as: an increase in the growth rate of the economy; an increase in its trade balance; a fall in its inflation rate; or an increase in its real—that is, inflation-adjusted—interest rate.

One simple model for determining the long-run equilibrium exchange rate is based on the quantity theory of money. The domestic version of the quantity theory says that a one-time increase in the money supply is soon reflected as a proportionate increase in the domestic price level. The international version says that the increase in the money supply is also reflected as a proportionate increase in the exchange rate. The exchange rate, as the relative price of money (domestic per foreign) can be viewed as determined by the demand for money (domestic relative to foreign), which is in turn influenced positively by the rate of growth of the real economy, and negatively by the inflation rate.

A defect of the international quantity theory of money is that it cannot account for fluctuations in the real exchange rate, as opposed to simply the nominal exchange rate. The real exchange rate is defined as the nominal exchange rate deflated by price levels (foreign relative to domestic). It is the real exchange rate that matters most for the real economy. If a currency has a high value in real terms, this means that its products are selling at less-competitive prices on world markets, which will tend to discourage exports and encourage imports. If the real exchange rate were constant, then purchasing power parity would hold: the exchange rate would be proportionate to relative price levels. Purchasing power parity does not, in fact, hold in the short run, not even approximately. It does not hold even for goods and services that are traded internationally. But purchasing power parity does tend to hold in the long run.

One elegant theory of exchange-rate determination is the late Rudiger Dornbusch’s “overshooting model.” In this theory, an increase in the real interest rate—due, for example, to a tightening monetary policy—causes the currency to appreciate more in the short run than it will in the long run. The explanation is that the only way international investors will be willing to hold any foreign assets, given that the rate of return on domestic assets is higher because of the monetary tightening, is if they expect the value of the domestic currency to fall in the future. This fall in the value of the domestic currency would make up for the lower rate of return on foreign assets. The only way the value of the domestic currency will fall in the future, given that the domestic currency’s value rises in the short run, is if it rises more in the short run than in the long run. Thus the term “overshooting.” An advantage of this theory over the international quantity theory of money is that it can account for fluctuations in the real exchange rate.

It is extremely difficult to predict in which direction exchange rates will move in the short run. Economists often view changes in exchange rates as following a random walk, which means that a future increase is as likely as a decrease. Short-run fluctuations are difficult to explain even after the fact. Some short-run movements no doubt reflect attempts by market participants to ascertain the future direction of macroeconomic fundamentals. But many short-run movements are hard to explain and may be due to ineffable determinants such as some vague “market sentiment” or speculative bubbles. Speculative bubbles are movements of the exchange rate that are not related to macroeconomic fundamentals, but that instead result from self-fulfilling changes in expectations. Those who trade foreign exchange for a living generally look at economists’ models of fundamentals when thinking about horizons of one year or longer. At horizons of a month or less, they tend to rely more on methods unrelated to economic fundamentals, such as “technical analysis.” A common technical-analysis strategy is to buy currency whenever the short-run moving average rises above the long-run moving average, and sell when it goes the other way.

By the 1990s, the richer countries had all but eliminated capital controls—that is, restrictions on buying and selling financial assets across their borders. The poorer countries, despite a degree of market opening, still have substantial restrictions. In the absence of barriers to movement of financial capital across borders, capital is highly mobile and financial markets are highly integrated. In this case, arbitrage is free to operate: investors buy assets in countries where they are cheap and sell them where they are expensive, and thereby bring prices into line. Arbitrage works to bring interest rates into parity across countries. The surest form of arbitrage brings about covered interest parity: it drives the forward discount into equality with the differential in interest rates.

Covered interest arbitrage brings about covered interest parity in the absence of major transactions costs, capital controls, or other barriers to the international movement of money. Again, the definition of covered interest parity is that the forward discount is equal to the differential in interest rates.

It is less clear if uncovered interest parity holds. Under uncovered interest parity, the differential in interest rates would equal not only the forward discount, but also the expected rate of future change in the exchange rate. It is hard to measure whether this condition in fact holds, because it is hard to measure investors’ private expectations. One reason uncovered interest parity could easily fail is the existence of an exchange-risk premium. If uncovered-interest parity holds, then countries can finance unlimited deficits by borrowing abroad, so long as they are willing and able to pay the going world rate of return. But if uncovered interest parity does not hold, then countries will find that the more they borrow, the higher the rate of interest they must pay.

The following theories explain the fluctuations in FX rates in a floating exchange rate regime (In fixed exchange regime, FX rates are decided by its government):

(a) International parity conditions: Relative Purchasing Power Parity, Interest Rate Parity, Domestic Fisher Effect, International fisher Effect. Though to some extent the above theories provide logical explanation for the fluctuations in exchange rates, yet these theories falter as they are based on challengeable assumptions [e.g., free flow of goods, services and capital] which seldom hold true in the real world.

(b) Balance of payments model: This model, however, focuses largely on tradable goods and services, ignoring the increasing role of global capital flows. It failed to provide any explanation for continuous appreciation of dollar during 1980s and most part of 1990s in face of soaring US current account deficit.

(c) Asset market model : views currencies as an important asset class for constructing investment portfolios. Assets prices are influenced mostly by people’s willingness to hold the existing quantities of assets, which in turn depends on their expectations on the future worth of these assets. The asset market model of exchange rate determination states that “the exchange rate between two currencies represents the price that just balances the relative supplies of, and demand for, assets denominated in those currencies.”

None of the models developed so far succeed to explain FX rates levels and volatility in the longer time frames. For shorter time frames (less than a few days) algorithm can be devised to predict prices. Large and small institutions and professional individual traders have made consistent profits from it. It is understood from above models that many macroeconomic factors affect the exchange rates and in the end currency prices are a result of dual forces of demand and supply. The world's currency markets can be viewed as a huge melting pot: in a large and ever-changing mix of current events, supply and demand factors are constantly shifting, and the price of one currency in relation to another shifts accordingly. No other market encompasses (and distills) as much of what is going on in the world at any given time as foreign exchange.

Supply and demand for any given currency, and thus its value, are not influenced by any single element, but rather by several. These elements generally fall into three categories: economic factors, political conditions and market psychology.

Theories of Foreign Exchange

After decades of relative neglect, economic theory, especially in its mathematical form, has taken a new life since the end of World War II.

The renaissance has included many aspects of international economics, but theories that purport to explain the levels and movements of parities and spot and forward exchange have been somewhat neglected. The result is that parities, spot and forward exchange are still a subject of research and controversy.

In its simplest form, the purchasing power parity theory affirms that the rate of exchange establishes itself at a point that will equalize the prices in any two countries. One of the functions of the rate of exchange, according to this theory, is to equalize the purchasing power of the several currencies.

A rate of exchange that does nothing more than equalize price levels will not necessarily prove to be an equilibrium rate. Foreign trade usually includes capital and unilateral transfer movements, and the purchasing power parity theory does not pretend to even out with them.

Adding together, nations produce many commodities that do not enter into international trade, and the prices of those domestic goods obviously cannot be equalized internationally. Furthermore, studies of European prices and exchange rates during inflationary periods of indicate that internal price levels are frequently determined by rates of exchange, and not the other way around.

The purchasing power parity rate of exchange does have the signal advantage, however, of being relatively determinable, whereas some theories do not provide a practical method of calculating an exchange rate or a par value. Also, since the merchandise trade is the most important element of world commercial relations, the theory does have at least limited applicability. For such reasons as these, it continues to have considerable acceptance as a workable approach to the general movement of exchange rates.

The balance of payments or the equilibrium theory of exchange rates affirms that the exchange rates tend to establish itself where it will maintain balance of payments equilibrium and eliminate surpluses and deficits. The theory might be valid if the exchange rates were allowed to float freely and attain their market, or equilibrium levels. Under the Bretton Woods system, however, limits are set to the fluctuations of exchange rates and government intervention in the exchange markets impedes the free movement of rates. Hence, the theory is more a statement of a tendency than a complete explanation.

The supply and demand theory, according to this one, the exchange rate is held to be determined by the supply and demand for foreign currencies. Actually, the supply and demand theory is not a theory, but instead a descriptive mechanism.

To say that a rate of exchange is established by supply and demand is to tell how a rate is established, but to say a little about the factors that determine it or why the rate is at a given level and not at some other level. All of the forces, substantive, technical, and psychological, that have impact on a rate of exchange, must, by the very nature of the market itself, act by determining the demand for, and the supply of foreign exchange.

The psychological theory--- the exchange rate is largely conditioned by the attitudes of those who deal in it. If, in their opinion, a rate is below its correct level or will rise in the future, they are inclined to but it; they thereby increase the demand for currency and work to raise its rate. If, on the other hand, they feel that the rate overvalues the currency or is likely to decline, they are apt to sell their holdings and thereby increase the market supply of the currency and push its rate down.

Lastly, the interest parity theory is the most widely accepted explanation of the magnitudes of forward exchange rates. it is based on the fact that short-term interest rates differ from country to country and also the fact that banks, which buy or sell foreign currencies forward, usually like to cover their positions by the purchase or sale of these currencies spot.

Theory 1 - Determination of exchange rates - why do they go up and down?

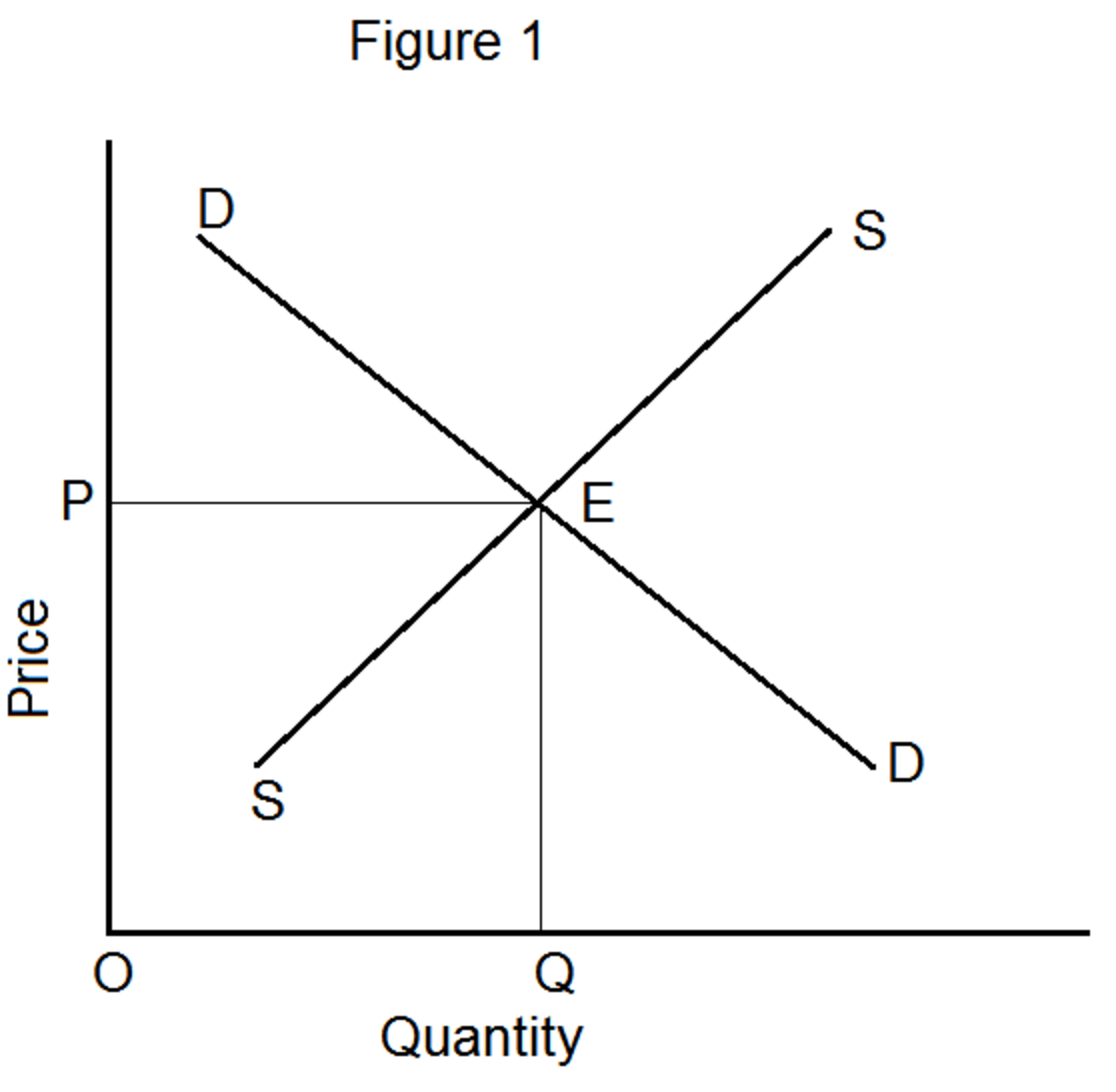

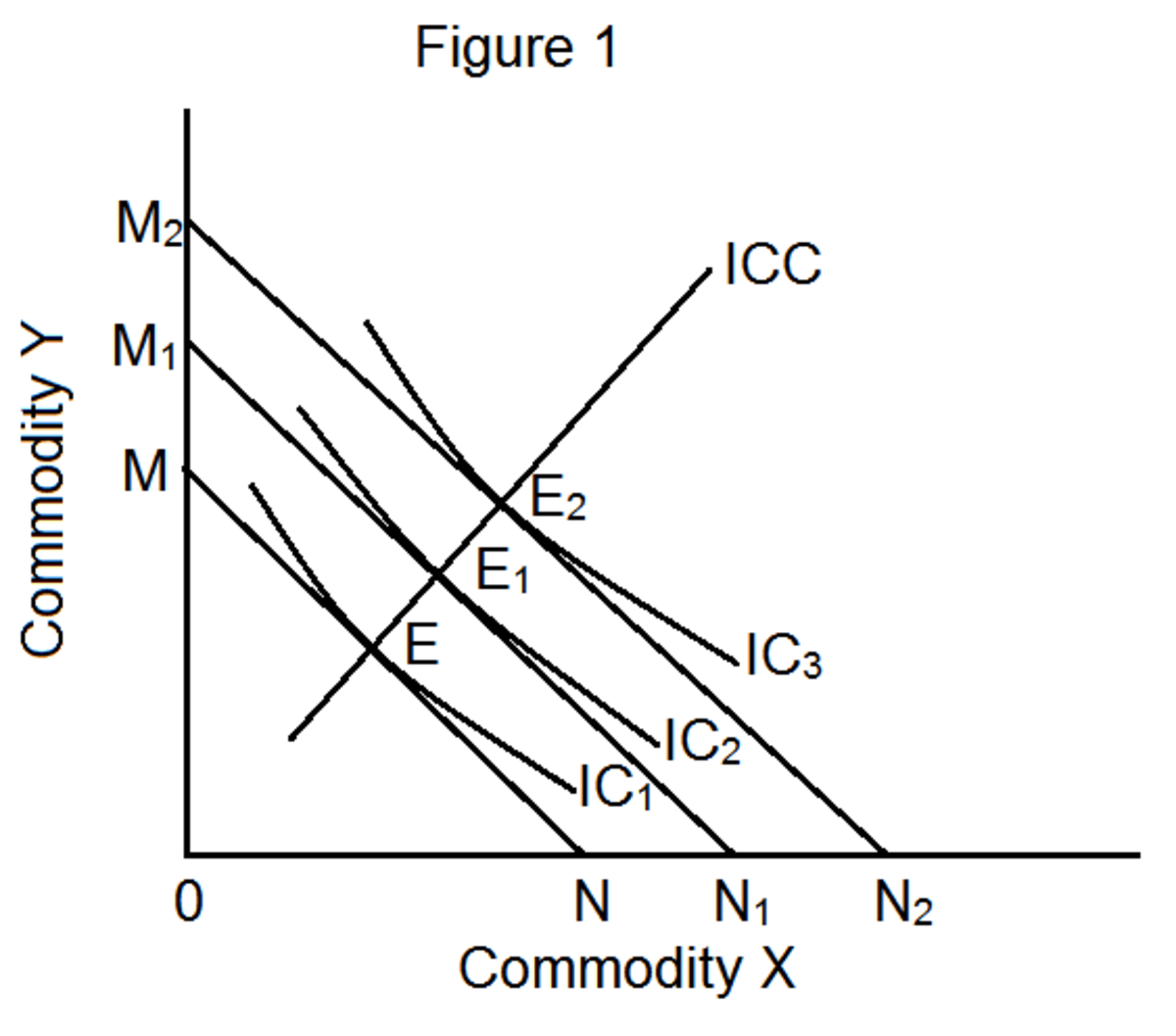

An exchange rate is a price - exactly the same as any other price - the amount you have to give up to acquire something else - in this case another currency. So an exchange rate is the price of one currency in terms of another. In other words it is the price you will pay in one currency to get hold of another. The price can be set in various ways. It may be fixed by the government or it could perhaps be linked to something external - for example, gold. However, the most likely alternative is that it will be fixed in a market. Since it is a price, it will be determined, like any other price, by demand and supply. This is the supply and demand of pounds traded on the foreign exchange market and is NOT the amount of sterling in circulation! A high level of demand for a currency will force up its price - the exchange rate. Where supply is equal to demand is the equilibrium exchange rate, as shown in the diagram below.

The demand for £ comes from people who are investing in the UK from abroad and so need pounds, or from firms who are buying UK exports. They will need pounds to be able to pay for the goods. The supply comes from people in the UK who are selling pounds. This may be because they have bought goods from overseas (imports), or it may simply be that they are investing in another country and so need the local currency. To get this they have to sell pounds in exchange for the other currency.

The equilibrium rate is where supply is equal to demand, and this will change as supply and demand changes. Say, for example, that interest rates increase. This will tend to attract more overseas investment into the UK. To invest here, they will need to buy pounds, and so the demand for pounds will rise. We can see this on the diagram below:

As we can see, both the exchange rate and the volume of currency traded have increased. This will not inevitably be the effect as there may be other factors affecting the exchange rate at the same time. A lot will also depend on whether the foreign exchange market expected the interest rate increase or not. However, supply and demand gives us a very useful tool for analysing movements in the exchange rate.

Theory 2 - Fixed v. floating - which will sink and which will swim?

The two principal ways of determining the exchange rate are either to fix it against another currency or to allow it to float freely in the market and find its own level. These two systems are respectively known as 'fixed' rates and 'floating' rates.

Fixed rates

A fixed exchange rate is a system where the exchange rate has a set value against another currency. For much of the post-war period sterling was fixed against the dollar and it was only floated in 1972 when a fixed rate became unsustainable. To maintain a fixed exchange rate, the government needs to have a significant level of foreign currency reserves. A fixed exchange rate does not keep itself at the same level. The government has to actively intervene in the markets to keep it at the fixed rate.

If, for example, there was an increase in demand for the currency (shown by a shift from D1 to D2 below), this would normally lead to the exchange rate increasing. However, the exchange rate is fixed and so the authorities have to counter the effect of the increase in demand. They do this by supplying more of the currency. In other words they sell sterling and buy other currencies instead. This shifts the supply curve to S2, and maintains the fixed rate.

To maintain the exchange rate, the government had to sell sterling and buy foreign currency, therefore increasing their holdings of foreign currency.

Floating rates

A floating exchange rate is one that is allowed to find its own level according to the forces of supply and demand. The demand for £ comes from people who are investing in the UK from abroad and so need pounds, or from firms who are buying UK exports. They will need pounds to be able to pay for the goods. The supply comes from people in the UK who are selling pounds. This may be because they have bought goods from overseas (imports), or it may simply be that they are investing in another country and so need the local currency. To get this they have to sell pounds in exchange for the other currency.

The equilibrium rate is where supply is equal to demand, and this will change as supply and demand changes. We can see this in the diagram below which shows an increase in demand for sterling - the shortage created on the market would lead to the exchange rate rising, settling at a new equilibrium level of €1.65

Arguments in Favour of a Fixed Rate

- Reduced risk in international trade - By maintaining a fixed rate, buyers and sellers of goods internationally can agree a price and not be subject to the risk of later changes in the exchange rate before contracts are settled. The greater certainty should help encourage investment.

- Introduces discipline in economic management - As the burden or pain of adjustment to equilibrium is thrown onto the domestic economy then governments have a built-in incentive not to follow inflationary policies. If they do, then unemployment and balance of payments problems are certain to result as the economy becomes uncompetitive.

- Fixed rates should eliminate destabilising speculation - Speculation flows can be very destabilising for an economy and the incentive to speculate is very small when the exchange rate is fixed.

Disadvantages of the Fixed Exchange Rate

- No automatic balance of payments adjustment - A floating exchange rate should deal with a disequilibrium in the balance of payments without government interference, and with no effect on the domestic economy. If there is a deficit then the currency falls making you competitive again. However, with a fixed rate, the problem would have to be solved by a reduction in the level of aggregate demand. As demand drops people consume less imports and also the price level falls making you more competitive.

- Large holdings of foreign exchange reserves required - Fixed exchange rates require a government to hold large scale reserves of foreign currency to maintain the fixed rate - such reserves have an opportunity cost.

- Loss of freedom in your internal policy - The needs of the exchange rate can dominate policy and this may not be best for the economy at that point. Interest rates and other policies may be set for the value of the exchange rate rather than the more important macro objectives of inflation and unemployment.

- Fixed rates are inherently unstable - Countries within a fixed rate mechanism often follow different economic policies, the result of which tends to be differing rates of inflation. What this means is that some countries will have low inflation and be very competitive and others will have high inflation and not be very competitive. The uncompetitive countries will be under severe pressure continually and may, ultimately, have to devalue. Speculators will know this and thus creates further pressure on that currency and, in turn, government.

Arguments in Favour of a Floating Exchange Rate

- Automatic balance of payments adjustment - Any balance of payments disequilibrium will tend to be rectified by a change in the exchange rate. For example, if a country has a balance of payments deficit then the currency should depreciate. This is because imports will be greater than exports meaning the supply of sterling on the foreign exchanges will be increasing as importers sell pounds to pay for the imports. This will drive the value of the pound down. The effect of the depreciation should be to make your exports cheaper and imports more expensive, thus increasing demand for your goods abroad and reducing demand for foreign goods in your own country, therefore dealing with the balance of payments problem. Conversely, a balance of payments surplus should be eliminated by an appreciation of the currency.

- Freeing internal policy - With a floating exchange rate, balance of payments disequilibrium should be rectified by a change in the external price of the currency. However, with a fixed rate, curing a deficit could involve a general deflationary policy resulting in unpleasant consequences for the whole economy such as unemployment. The floating rate allows governments freedom to pursue their own internal policy objectives such as growth and full employment without external constraints.

- Absence of crises - Fixed rates are often characterised by crises as pressure mounts on a currency to devalue or revalue. The fact that, with a floating rate, such changes are automatic should remove the element of crisis from international relations.

- Flexibility - Post-1973 there were great changes in the pattern of world trade as well as a major change in world economics as a result of the OPEC oil shock. A fixed exchange rate would have caused major problems at this time as some countries would be uncompetitive given their inflation rate. The floating rate allows a country to re-adjust more flexibly to external shocks.

- Lower foreign exchange reserves - A country with a fixed rate usually has to hold large amounts of foreign currency in order to prepare for a time when they have to defend that fixed rate. These reserves have an opportunity cost.

Disadvantages of the Floating Rate

- Uncertainty - The fact that a currency changes in value from day to day introduces instability or uncertainty into trade. Sellers may be unsure of how much money they will receive when they sell abroad or what their price actually is abroad. Of course the rate changing will affect price and thus sales. In a similar way importers never know how much it is going to cost them to import a given amount of foreign goods. This uncertainty can be reduced by hedging the foreign exchange risk on the forward market.

- Lack of investment - The uncertainty can lead to a lack of investment internally as well as from abroad.

- Speculation - Speculation will tend to be an inherent part of a floating system and it can be damaging and destabilising for the economy, as the speculative flows may often differ from the underlying pattern of trade flows.

- Lack of discipline in economic management - As inflation is not punished there is a danger that governments will follow inflationary economic policies that then lead to a level of inflation that can cause problems for the economy. The presence of an inflation target should help overcome this.

- Does a floating rate automatically remedy a deficit? - UK experience indicates that a floating exchange rate probably does not automatically cure a balance of payments deficit. Much depends on the price elasticity of demand for imports and exports. The Marshall-Lerner condition says that a depreciation in the exchange rate will help improve the balance of payments if the sum of the price elasticities for imports and exports is greater than one.

- Inflation - The floating exchange rate can be inflationary. Apart from not punishing inflationary economies, which, in itself, encourages inflation, the float can cause inflation by allowing import prices to rise as the exchange rate falls. This is, undoubtedly, the case for countries such as UK where we are dependent on imports of food and raw materials.

Theory 3 - Market intervention - how can the government change things?

The Bank of England can act on behalf of the government to influence the level of the exchange rate. They have not done this since the ERM crisis of 1992, but it remains a possible option. The foreign exchange market now trades on such a significant scale (a net daily turnover in London of over $650 billion), that it is difficult for any one government to influence the markets. However, governments acting in a concerted way could certainly have an impact.

If they want to intervene, the government will need to use their foreign exchange reserves. They will need to buy or sell foreign currency as appropriate to try to influence the market. Say, for example, that the exchange rate has been depreciating for some time because of a lot of selling of the pound, and the government wants to try to slow its fall (or even reverse it). They will need to increase the level of demand for the currency, and they do this by buying sterling and selling other currencies.

We can see all this on the diagram below. The selling of sterling pushes the supply curve to the right (S1 to S2) and is forcing the exchange rate down.

The government decides to act, and so they sell various currencies (perhaps dollars, euro or yen) and buy sterling in exchange. This increases the demand for sterling, and pushes the demand curve to D2. The pound has still fallen overall, but the government's action has slowed the fall.

If the opposite was happening, and sterling was rising, then the government would need to buy foreign currency and sell sterling. This would increase the supply of sterling and help to slow down the appreciation.

Theory 4 - Effects of exchange rate changes - why do they matter?

Exchange rate changes can have a significant effect on the economy. Let's take the example of a depreciation of the exchange rate, and see what impact this has.

If the exchange rate falls, this changes the relative prices of imports and exports. Exports will appear to become relatively cheaper in other currencies, and imports will appear to be more expensive. Because we buy imports, they are included as part of the retail price index, and so if the price of imports goes up, this could be inflationary especially as in the UK we import a lot of raw materials and semi-finished products. There we have the first effect of a depreciation - it could trigger inflationary pressures in the economy.

The effects on aggregate demand may compound this inflationary impact. Since exports are relatively cheaper overseas, this should increase the demand for them. In addition the demand for imports should fall. The combination of the two will have a positive impact on aggregate demand because net exports is one of the components of the AD function (AD= C+I+G+(X-M) How much the demand increases depends on the price elasticity of demand for exports, but the demand should certainly grow. Growth in aggregate demand could also be inflationary if the economy is close to its capacity. On the diagram below you can see the shift in aggregate demand (AD1 to AD2) pulling up the price level (demand-pull inflation).

In the long-run the effect of the depreciation on the balance of payments is far from certain. The impact depends on how much the demand for imports and exports change. That depends on the price elasticity of demand for imports and exports. When the exchange rate falls imports get more expensive and exports cheaper. That should raise the demand for exports and lower the demand for imports. However, for exports we still receive the same amount in sterling. They are cheaper in the local currency, but we still receive the same amount in sterling. Imports, however, cost us more in sterling. So the overall effect on the balance of payments depends on the price elasticity of exports and imports.

Let us look at a simple example to illustrate:

Assume the exchange rate between the £ and the € is £1 = €2. A good, X, in the UK is priced at £5. At this exchange rate 100 of these items are purchased from abroad - export earnings are therefore £500. A product Y in Europe is locally priced at €5, The UK buys 200 of these items at the current exchange rate. This means that we have to give up £2.50 to buy each unit. Total expenditure on imports therefore is £500. At this point the balance of payments is 0.

Let us now assume that the exchange rate depreciates from £1 = €2 to £1 = €1. Europeans buying good X from the UK will now have to give up only €5 to acquire the good rather than the €10 they had to previously. Given that the product appears cheaper we would expect demand for exports to rise. UK buyers of good Y from Europe however now have to give up £5 to acquire the necessary euro to buy the product. It appears to the UK buyer that prices have risen and we would expect demand for imports to fall. The price of exports has fallen by 50% whilst the price of imports appears to have risen by 100%. Now let us look at the impact on the actual demand for imports and exports given two different scenarios.

Scenario 1:

The Price Elasticity of Demand (PED) for exports is -1.4 and the PED for imports is -0.2.

Demand for exports would rise by 1.4 times the fall in price and so would rise by 70 units. In this case, export earnings would now be 170 x £5 = £850.

Demand for imports would fall by 0.2 x the change in price and so would fall by 20% - a decrease of 40 units. Expenditure on imports would now be 160 x £5 = £900.

We would now have a balance of payments deficit of £50!

Scenario 2:

The PED of exports is -0.8 and the PED for imports is -0.5.

Demand for exports would rise by 0.8 x the change in price = 40 units. Total export earnings would be 140 x £5 = £700.

Demand for imports would fall by 0.5 x the change in price (100%) = 50%. Import expenditure would now be 100 x £5 = £500.

In this situation the balance of payments would be in surplus at +£200

The 'Marshall-Lerner' condition says that if the sum of the price elasticities for imports and exports is greater than 1, then the balance of payments will improve. The evidence for the UK suggests that the condition holds in the long-run, but not in the short-run. This will mean that when the exchange rate depreciates, the balance of payments will initially deteriorate, but in the long-run it will improve. This gives what is known as a 'J-curve effect'. This effect is shown below.

The effect occurs because it will take time for the exchange rate changes to be factored in by decision makers - contracts will have been signed for example, which will not immediately reflect any change in the exchange rate.

Theory 5 - Exchange rate jargon - jargon-busting guide

There is a lot of jargon associated with exchange rates. In this theory section we look at some of this jargon, and see what it means.

Spot exchange rates

The spot exchange rate is the rate existing in the market at any given moment. It can be considered as the rate of exchange for immediate delivery of the currency. The spot rate will change all the time according to the changes in supply and demand in the market.

Forward exchange rates

The forward exchange rate is a rate for a given time in the future. A price is agreed now for an exchange at some time in the future (often 3 months or so). Whatever happens to the spot rate between now and then, the contract will be met at the rate that was agreed. Companies may use the forward market to protect themselves against the foreign exchange risk. They know they can buy at a guaranteed rate for the future, and so can plan ahead. This process is called 'hedging' against risk. The existence of the forward market also creates the potential for speculation. Depending on the reason for buying or selling the currency the dealer could end up better off or worse off.

Purchasing Power Parity

The purchasing power parity exchange rate is the exchange rate between two currencies, which would enable exactly the same basket of goods to be purchased. In other words, the rate at which purchasing power will be the same in both countries. For example, say a basket of goods cost $50 in the USA, and the same basket cost £25 in the UK. The PPP rate between the £ and the $ would then be £1=$2. The PPP rate is often used when trying to work out consistent measures between countries like GDP or standard of living. It will generally be different to the actual equilibrium exchange rate, though it will be a factor influencing it.

The PPP relationship becomes a theory of exchange rate determination by introducing assumptions about the behavior of importers and exporters in response to changes in the relative costs of national market baskets. Recall, in the story of the law of one price, when the price of a good differed between two country's markets, there was an incentive for profit-seeking individuals to buy the good in the low price market and resell it in the high price market. Similarly, if a market basket, containing many different goods and services, costs more in one market than another, we should likewise expect profit-seeking individuals to buy the relatively cheaper goods in the low cost market and resell them in the higher priced market. If the law of one price leads to the equalization of the prices of a good between two markets, then it seems reasonable to conclude that PPP, describing the equality of market baskets across countries, should also hold.

However, adjustment within the PPP theory occurs with a twist compared to adjustment in the law of one price story. In the law of one price story, goods arbitrage in a particular product was expected to affect the prices of the goods in the two markets. The twist that's included in the PPP theory is that arbitrage, occurring across a range of goods and services in the market basket, will affect the exchange rate rather than the market prices.

The PPP Equilibrium Story

To see why the PPP relationship represents an equilibrium we need to tell an equilibrium story. An equilibrium story in an economic model is an explanation of how the behavior of individuals will cause the equilibrium condition to be satisfied. The equilibrium condition is the PPP equation developed above,

The endogenous variable in the PPP theory is the exchange rate. Thus, we need to explain why the exchange rate will change if it is not in equilibrium. In general there are always two versions of an equilibrium story, one in which the endogenous variable (Ep/$ here) is too high, and one in which it is too low.

PPP Equilibrium Story 1 - Let's consider the case in which the exchange rate is too low to be in equilibrium. This means that,

where Ep/$ is the exchange rate that prevails on the spot market and, since it is less than the ratio of the market basket costs in Mexico and the US, is also less than the PPP exchange rate. The right-hand side of the expression is rewritten to show that the cost of a market basket in the US evaluated in pesos, CB$Ep/$, is less than the cost of the market basket in Mexico also evaluated in pesos. Thus, it is cheaper to buy the basket in the US, or, more profitable to sell items in the market basket in Mexico.

The PPP theory now suggests that the cheaper basket in the US will lead to an increase in demand for goods in the US market basket by Mexico, and, as a consequence, will increase the demand for US dollars on the foreign exchange market. Dollars are needed because purchases of US goods require US dollars. Alternatively, US exporters will realize that goods sold in the US can be sold at a higher price in Mexico. If these goods are sold in pesos, the US exporters will wantto convert the proceeds back to dollars. Thus, there is an increase in US dollar demand (by Mexican importers) and an increase in peso supply (by US exporters) on the Forex. This effect is represented by a rightward shift in the US dollar demand curve in the adjoining diagram. At the same time, US consumers will reduce their demand for the pricier Mexican goods. This will reduce the supply of dollars (in exchange for pesos) on the Forex which is represented by a leftward shift in the US dollar supply curve in the Forex market.

Both the shift in demand and supply will cause an increase in the value of the dollar and thus the exchange rate, Ep/$, will rise. As long as the US market basket remains cheaper, excess demand for the dollar will persist and the exchange rate will continue to rise. The pressure for change ceases once the exchange rate rises enough to equalize the cost of market baskets between the two countries and PPP holds.

PPP Equilibrium Story 2 - Now let's consider the other equilibrium story, that is, the case in which the exchange rate is too high to be in equilibrium. This implies that,

The left-hand side expression says that the spot exchange rate is greater than the ratio of the costs of market baskets between Mexico and the US. In other words the exchange rate is above the PPP exchange rate. The right-hand side expression says that the cost of a US market basket, converted to pesos at the current exchange rate, is greater than the cost of a Mexican market basket in pesos. Thus, on average US goods are relatively more expensive while Mexican goods are relatively cheaper.

The price discrepancies should lead consumers in the US, or importing firms, to purchase less expensive goods in Mexico. To do so, they will raise the supply of dollars in the Forex in exchange for pesos. Thus, the supply curve of dollars will shift to the right as shown in the adjoining diagram. At the same time, Mexican consumers would refrain from purchasing the more expensive US goods. This would lead to a reduction in demand for dollars in exchange for pesos on the Forex. Hence the demand curve for dollars shifts to the left. Due to the demand decrease and the supply increase, the exchange rate, Ep/$, falls. This means that the dollar depreciates and the peso appreciates.

Extra demand for pesos will continue as long as goods and services remain cheaper in Mexico. However, as the peso appreciates (the $ depreciates) the cost of Mexican goods rises relative to US goods. The process ceases once the PPP exchange rate is reached and market baskets cost the same in both markets.

Adjustment to Price Level Changes Under PPP

In the PPP theory, exchange rate changes are induced by changes in relative price levels between two countries. This is true because the quantities of the goods are always presumed to remain fixed in the market baskets. Therefore, the only way that the cost of the basket can change is if the goods' prices change. Since price level changes represent inflation rates, this means that differential inflation rates will induce exchange rate changes according to the theory.

If we imagine that a country begins with PPP, then the inequality given in equilibrium story #1,

,

can arise if the price level rises in Mexico (peso inflation), if the price level falls in the US ($ deflation), or if Mexican inflation is more rapid than US inflation. According to the theory, the behavior of importers and exporters would now induce a dollar appreciation and a peso depreciation.In summary,an increase in Mexican prices relative to the change in US prices (i.e., more rapid inflation in Mexico than in the US) will cause the dollar to appreciate and the peso to depreciate according to the purchasing power parity theory.

Similarly, if a country begins with PPP, then the inequality given in equilibrium story #2,

,

can arise if the price level rises in the US ($ inflation), the price level falls in Mexico (peso deflation) or if US inflation is more rapid than Mexican inflation. In this case, the inequality would affect the behavior of importers and exporters and induce a dollar depreciation and peso appreciation. In summary, more rapid inflation in the US would cause the dollar to depreciate while the peso would appreciate.

Effective Exchange Rate

The effective exchange rate is also called the 'sterling index' or perhaps the 'sterling trade-weighted index'. It is an exchange rate calculated from a basket of currencies, and can perhaps best be thought of as an average exchange rate. Each of the currencies included is weighted according to its importance to us. This is worked out from the amount of trade we do with that country. The currency of a country that we do a large amount of trade with will have a higher weight than one whom we do relatively little trade with. The effective exchange rate can be a useful indicator, as it shows overall exchange rate changes. An individual currency may be affected by factors unique to that country, but the effective exchange rate will still give an overall indication.