The Heidi Game: A Milestone in Broadcast History

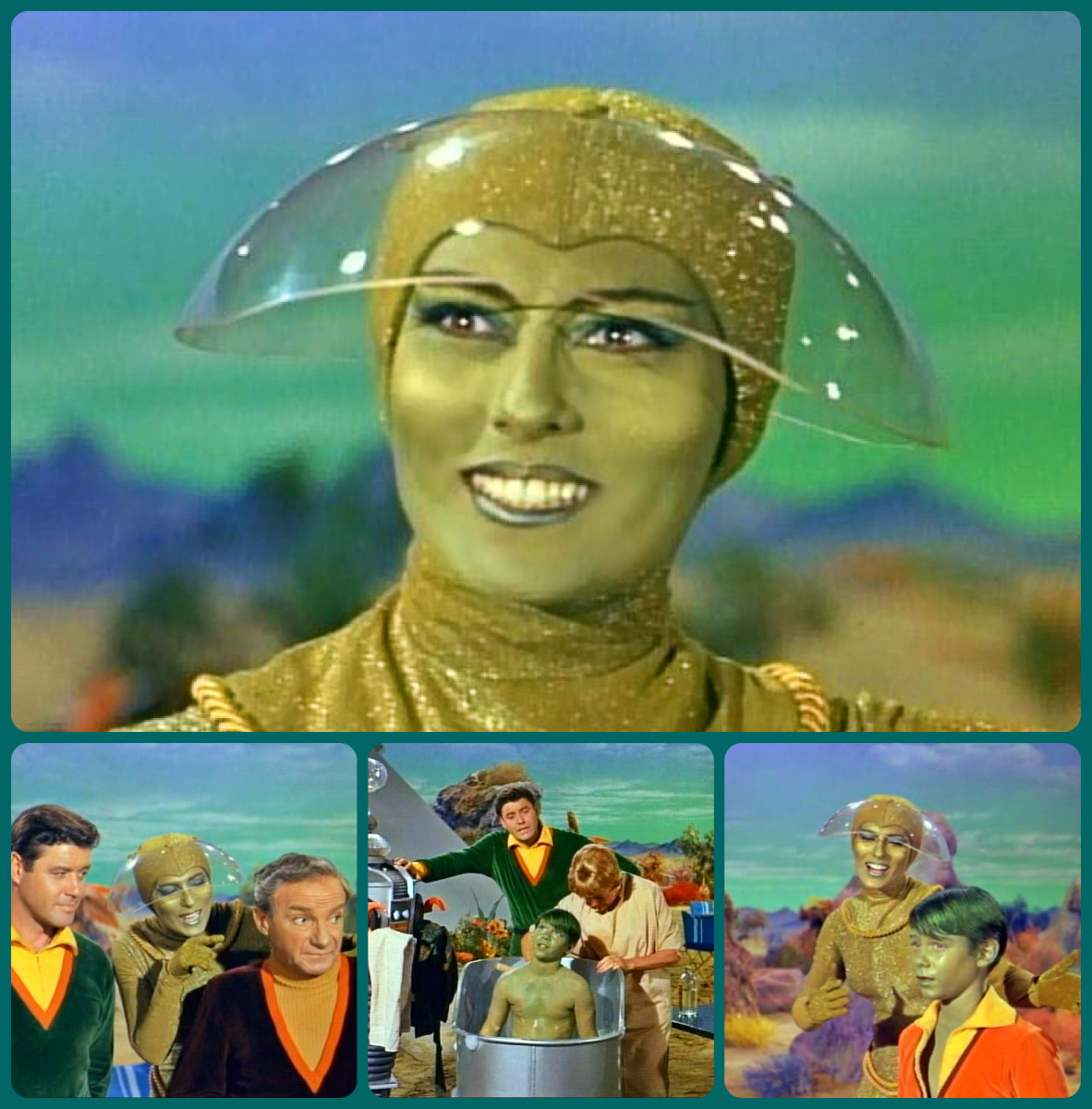

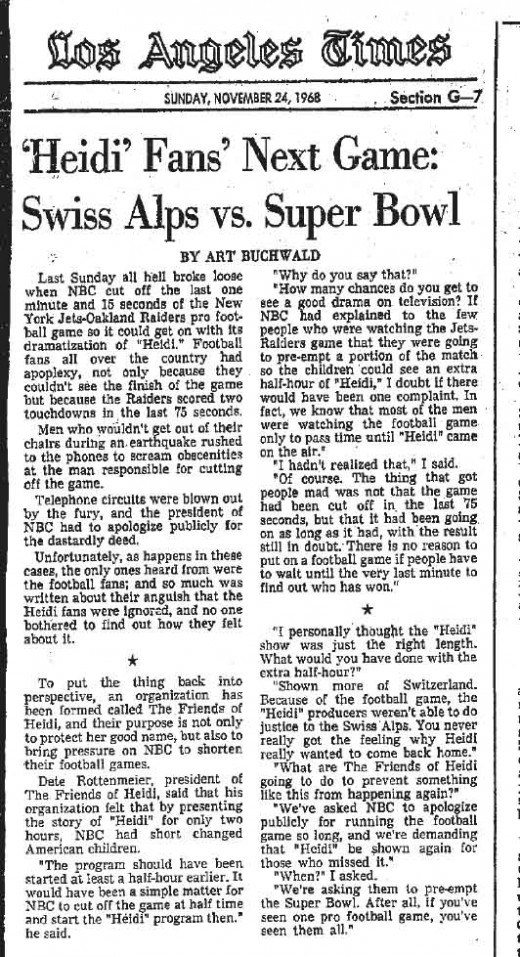

On a November night in 1968, American TV viewers were shocked by the most dramatic and jarring juxtaposition of images in the history of broadcasting: a burly running back, clad in helmet and shoulder pads and about to be crushed by an oncoming linebacker, instantly gave way to a little blonde Swiss girl walking next to a bearded shepherd on the side of a mountain.

The story of the events which led up to this clash of images is one of the great curiosities in the history of sports and television, and a benchmark for how much the world has changed since.

In 1968 there was no cable television, no satellite transmission, no home video recording equipment and only three networks in American television: NBC, CBS and ABC. Viewers who wished to watch something other than what the Big Three were showing had to depend on local affiliates to substitute their own programming in place of the network feed, which came not over the air but by telephone transmission through coaxial cables.

Every night between 12 midnight at 1 AM all programming ceased, usually after the playing of the National Anthem. Images were replaced by static. It was during 1968 that multimillionaire recluse Howard Hughes bought WLAS in Las Vegas, allegedly so that he could order programming throughout the night.

So different was the technological landscape of television then as compared to now that someone who simply wanted to watch TV around the clock had to buy his own station to make it possible.

As had been the case during the heyday of radio and the formative years of television, programs were often bought exclusively by single advertisers, who stipulated how and when their products would be promoted during airtime, usually during limited interruptions. In November of 1968, the Timex watch company had such an arrangement with the NBC network. It had paid for the filmed presentation of the classic children’s book Heidi by Swiss-German author Johanna Spyri. The broadcast was to begin at exactly seven o’clock on the night of Sunday November 17, without fail. Timex had been explicit in its demands that the program start on time, and NBC executives had promised that it would.

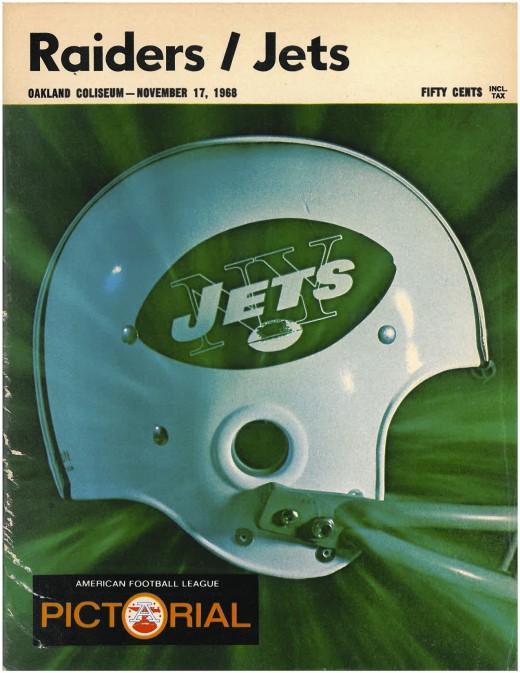

In the programming slot just ahead of Heidi the network would be airing an American Football League (AFL) game from Oakland, California between the New York Jets and the Oakland Raiders. The Jets and Raiders, two of the strongest teams from the upstart league which had started a few years earlier to rival the National Football League (NFL), were bitter rivals. NBC had exclusive rights to AFL games, which were beginning to challenge NFL games in popularity. Two short months later, the Jets would become the first AFL team to defeat an NFL team in a championship game, Super Bowl III, when they upset the Baltimore Colts.

But this was yet to be determined. In November the Raiders seemed nearly equal to the Jets. The game was to begin at 4PM eastern time, and in that era of limited commercial interruptions and predominantly running offenses which kept the game clock moving, no football broadcast on NBC had ever lasted a full three hours. Network executives seemed certain, on the basis of past experience, that they would be able to satisfy the demands of the two demographically different audiences: the mothers and small children who had been promised Heidi at 7 and the sports-crazed men who were absorbed in the football game.

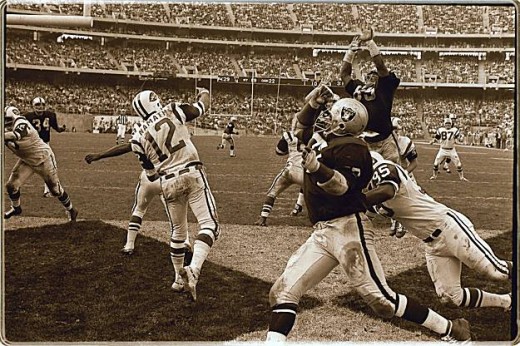

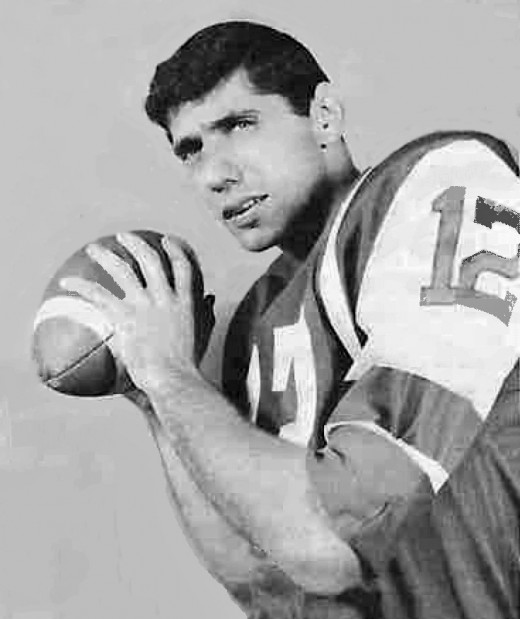

However, this particular game seemed to defy all expectations. The lead swung back and forth between the two teams, highlighted by big plays and an unusual (for the era) reliance on the passing of Raiders quarterback Darryl Lamonica and Jets quarterback Joe Namath. There were multiple stoppages for injuries as the players from both squads viciously attacked each other. Namath was intentionally kneed in the groin at one point and Jets defensive player Joe Hudson, who was thrown out of the game for an illegal hit, stuck his middle finger at the stands full of Oakland supporters as he walked off the field. Both teams used their full complement of six timeouts during the game.

The extraordinary competitiveness, drama and violence of the game absorbed the NBC executives who were monitoring the time. At around 6:15 Dick Cline, the NBC network supervisor of sports broadcasts, began worrying about whether the game would be finished by seven. Under strictest orders from NBC brass, he had been told to switch the network feed in the Eastern time zone to Heidi at seven o’clock sharp. But something extraordinary then happened.

Scotty Connal, the executive producer of NBC sports, who had been watching the game from his home in Connecticut, had a sudden change of heart when he realized this particular football game may have been the greatest ever played. He called several top executives at NBC, including network president Julian Goodman, who was also watching the game, to get permission to run the game to the end. Despite what they had promised Timex, Goodman and other NBC brass decided that they would not allow any of the game to be cut off, that they would air the game fully until its conclusion. They then attempted to call Cline to give the revised order.

But in the era before cell phones, when all phone communication traveled through wires, they had problems that would be unimaginable today. The very executives in charge of NBC were unable to get through to their programmers because the network's switchboard operators were overwhelmed. Irate calls was pouring in from football fans who, fearing that they would miss the dramatic ending of the greatest game ever played, were complaining about the much-ballyhooed start of Heidi at exactly seven.

As the dreaded hour approached, the Jets claimed the lead 32-29 with slightly over one minute remaining on the game clock, and kicked off to Oakland, which started possession on its own 22-yard line. Cline, who never got the messages from the upper execs at NBC, gave the order to pull the plug on the East Coast feed just as Oakland running back Charlie Smith had caught a pass on the ensuing play and was racing ahead toward an approaching tackler at the Oakland 40-yard line. Oakland ultimately scored on their possession, recovered a New York fumble on the ensuing kickoff for another score, and won the game 43-32.

Realizing the firestorm of wrath they would be facing from football fans, NBC programmers ran a crawling message on the lower screen of the Heidi feed advising viewers of the final score of the Jets/Raiders game. The message came at the emotional moment when Heidi’s wheelchair-bound cousin was trying to jump up out of her wheelchair and walk. The message succeeded only at angering the Heidi viewers for ruining the scene and the remaining football fans for having denied them the chance to watch Oakland’s final two game-deciding scores.

For days the controversy was mocked and joked about, not only by ABC and CBS, but by NBC itself, which in the spirit of good humor placed a newspaper ad proclaiming the success of Heidi, filled with praise from various critics, and one quote from Jets star QB Namath: “I didn’t get a chance to see it, but I hear it was great.” On the 20th anniversary of the event in 1988 Namath and famed Raiders coach John Madden, an assistant coach with the Raiders in 1968, playfully argued about the merits of the two teams who had been involved in the famous game.

The aftermath of the foul-up was swift and permanent. In the years since, all sports leagues have stipulated in their network contracts that the broadcasts of their events must be carried to completion. In 1968 Timex was king. Shortly after “The Heidi Game,” when the AFL and NFL merged in 1970, the NFL assumed the title of king that it has maintained ever since.

NFL Films footage from 1968 game.

- The Heidi Bowl

The Raiders defeated the Jets in the greatest game you never saw.

© 2015 James Crawford