Book Summary: Nurture Shock

Introduction

It might seem as though parenting should be instinctive and if not instinctive then logical. For what better way to proceed than to employ tactics that make sense?

Ironically, this book reveals just how wrong our "instincts" and "logic" can be when it comes to children. Everything that makes sense to us flies in the face of how children operate.

If you do not want to make those mistakes, this is a must read for every parent. This is a summary of the salient points from the book, however, I highly recommend reading the book for yourself.

Chapter 1: The Inverse Power of Praise

"Sure, he's special. But new research suggests that if you tell him that, you'll ruin him. It's a neurobiological fact."

It is commonly assumed that if you want a child to perform well, you should encourage him by praising him on his achievements. Not so. Research reveals that praising children can actually have a negative effect on their achievements. Unlike adults who perform better with such encouragements, children react different. Traditional ways of praising a child - "You're such a clever boy" - merely serve to instill uncertainty in a child.

From such praise, a child believes that intelligence is finite and inherited. What he has is all he will ever have. If the work gets difficult, he becomes fearful to apply himself in the event that he fails. Failure to such a child denotes stupidity and in order to avoid looking stupid, he stops trying and refuses to attempt anything that might possibly be beyond his ability.

Does that mean children should never be praised? Not necessarily. It means that praise for children needs more specific. Here are some tips for effective praise for children:

- focus on effort not on ability.

- be specific, e.g. "You worked really hard on that math problem!" As opposed to, "You did great."

- be honest - if you can't give honest praise, don't offer anything. If a child detects the praise is false, he will distrust all other praise, even that which is true.

- intermittent so that your child learns to persist through frustrating periods without rewards.

Chapter 2: The Lost Hour

"Around the world, children get an hour less sleep than they did thirty years ago. The cost: IQ points, emotional well-being, ADHD, and obesity."

Here's the problem: children today are averaging an hour less sleep a night than children 30 years ago.

Sleep studies performed on children are revealing that a single lost hour of sleep a night can:

- reduce academic performance

- affect emotional stability

- increase the incidence of medical conditions such as obesity and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Sleep deprivation during the formative years of a child’s brain could lead to permanent changes in brain structure that cannot be reversed even with “catch-up” sleep.

1. The Effect of Sleep Deprivation on Academic Performance

A sleep deprivation study on a group of elementary students revealed that sixth graders, missing one hour of sleep a night, performed in class at the level of a fourth grader. Effectively, losing one hour of sleep a night can reduce a child’s cognitive maturation and development by as much as two years. Additionally, delaying a child’s bedtime by one hour over the weekend can lead to a seven point reduction in IQ scores. Even 15 minutes of sleep can mean the difference between an average grade A student and an average grade B student.

Sleep deprivation impairs a child’s brain by reducing the plasticity of that child’s brain cells. The brain cells are then unable to form the connections required to record memory. Therefore, children suffering from sleep deprivation are not able to retain information learned in class. Sleep is vital for the synthesis and storage of memories. During sleep, the brain moves information learned during the day into more efficient storage areas within the brain. The more a child learns during the day, the more sleep is required to consolidate the memories associated with the information learned.

Sleep deprivation also affects the body’s ability to draw glucose from the bloodstream. This inability to access basic energy reserves from the body affects the prefrontal cortex of the brain. The prefrontal cortex is responsible for executive functions such as fulfilling goals, predicting outcomes, and perceiving the consequences of actions. When the brain is tired, it is unable to look beyond a wrong answer and come up with alternative solutions. It is also unable to control impulses such as postponing entertaining diversions in order to complete study goals.

2. The Effect of Sleep Deprivation on Emotional Stability

Studies have also shown an interesting effect of sleep on different parts of the brain. For instance, sleep deprivation impacts the hippocampus more so than the amygdala. The hypocampus is responsible for processing positive memories, while the amygdala processes negative stimuli. As a result, children who are sleep deprived are less able to recall pleasant memories compared to melancholic ones.

3. The Effect of Sleep Deprivation on Weight

Sleep studies have revealed that children who sleep less are, on average, fatter than children who receive adequate sleep. Children who received “less than eight hours of sleep have about a 300 percent higher rate of obesity than those who get a full ten hours of sleep.” The two-hour window revealed a “dose-response” relationship between sleep and obesity.

How does sleep deprivation affect weight gain?

- Lack of sleep has been shown to increase the hormone that signals hunger and reduce the hormone that suppresses appetite.

- Lack of sleep increases the levels of the stress hormone cortisol which stimulates the body to make fat.

- Sleep deprivation disrupts the normal release of human growth hormone which is essential for breaking down fat.

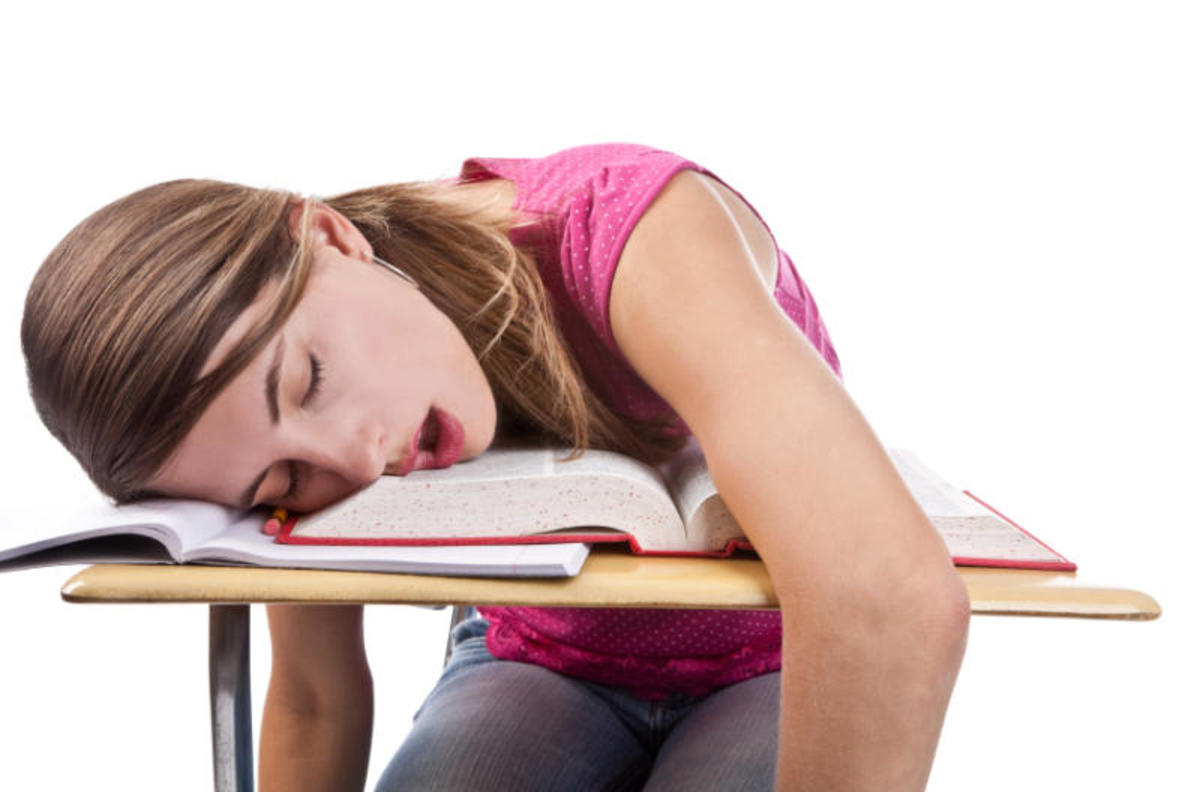

Teenagers and Sleep

The problem with teenagers and sleep is that during puberty, teenagers go through “phase shift” in their circadian rhythms which keeps them up later – about 90 minutes later.

In adults and prepubescent children, the brain begins to produce melatonin when it gets dark outside. Melatonin is responsible for making us feel sleepy. Unfortunately, in teenagers, the release of melatonin does not occur for another 90 minutes. This alone is not particularly significant until you combine it with an early start the following morning. When the alarm rings in the morning, teenagers are still producing melatonin and are prone to falling back to sleep – usually in the first two periods of school.

Since teenagers are also affected by sleep deprivation in the same way, this inadvertent reduction in sleep has a significant impact. In fact, it is believed that the lack of sleep that teenagers suffer is also related to the common “moodiness” observed in teenagers. Even those that do not suffer from clinical depression are likely to be affected by some level of melancholy.

Chapter 3: Why White Parents Don't Talk About Race

"Does teaching children about race and skin color make them better off or worse?"

The general belief is that children are born "colour blind" and it is the influence of parents that cause children to develop racial prejudices. We believe that if we don't want our children to discriminate, we should avoid pointing out differences between the races and treat individuals of different skin colour the same. The research, however, suggests differently.

It appears that children as young as six months have an inherent tendency to discriminate against other individuals who are different from them. It doesn’t necessarily have to be skin colour differences. Any difference that they observe can be a source for discrimination. It relates to a child's search for their identity and the assumption that people who are similar on the exterior are also more likely to be similar on the inside. That is, they are more likely to like-minded.

One study that made this evident was when they took a class and divided them into two groups. One group wore red shirts and the other wore blue shirts. No mention was ever made to the colour of the shirts they wore. There were no competitions nor segregation. During play time, the red and blue shirts were free to intermingle as they desired.

After a period of time, the examiner questioned both red and blue shirts. When the red shirts were asked who they thought were more likely to be nice, they answered the red shirts. When the red shirts were asked who they thought were more likely to be mean, they answered the blue shirts. Likewise, when the blue shirts were asked who they thought were more likely to win a competition, they answered the blue shirts. Despite there being no references made to the difference in shirt colour, the children instinctively picked up on it and made their own assumptions based on that external difference.

The same thing happens with race. This is further aggravated by parents who avoid discussing racial differences with their children. Because we are so conscious about being politically correct, we have taken it to the extremes by refusing to acknowledge such external differences to our children. Yet, studies are showing that this is the wrong tack to take with a child who doesn’t understand why there are such differences and what it all means. If left to their own devices, they will form their own opinions about the differences - which usually leads to racial discrimination - unless we educate them.

Therefore, if we want to raise children who are better able to accept racial differences, we need to talk about those differences. Just as we discuss the differences between boys and girls, we need to be able to discuss the differences in skin colour and the fact that we’re all the same underneath.

It isn’t enough to simply make vague statements that everyone is the same. A child cannot understand such broad, sweeping statements. The discussion needs to be very specific – so specific that it often makes parents uncomfortable talking about it. Yet, if we want our children to accept other people from other races, we need to talk about it and explore our children’s feelings about it.

Another thing that Bronson and Merryman discovered was that children were beginning to form their own opinions about racial differences from as early as 3 years old. At this age, most parents aren’t even aware of the need to discuss race. By the time parents bring up the topic, a child has already formed so many internal ideas about race that it is much harder to correct prejudices.

In short, parents need to talk about racial differences, explore the issues and do so from as early as 3 years old.

Chapter 4: Why Kids Lie

"We may treasure honesty, but the research is clear. Most classic strategies to promote truthfulness just encourages kids to be better liars."

We all know that kids lie. When they are toddlers, the belief is that they don’t know the difference between the truth and a lie because many kids have active imaginations. As a parent, it is usually easy to spot the early lies because of inconsistencies and the child’s inability to make up realistic lies on the spot. As the child gets better at it, the research shows that both parents and teachers who know the child well are both equally as good as distinguishing the lies as they are at guessing.

Most parents think they know their children well enough to tell when they are lying. Most parents also think that their children rarely lie. And much of the current literature advises parents that lying is just a phase and that most children generally “grow out of it”. Unfortunately, the research shows otherwise.

What does the research show about children and lying?

1. Children learn to lie a lot earlier than we presume.

By the fourth birthday, almost all children will start experimenting with lying. Children with older siblings will begin even earlier.

Parents generally fail to address early childhood lying thinking that it is harmless. Parents make the false assumption that their children are too young to understand what lies are or that they are wrong. But this is a misconception. Most children start out believing that all lying is wrong. As they grow up, they begin to learn that some lies are okay (e.g. white lies).

Parents believe that as the child grows older and learns the distinction between the truth and a lie, they will eventually stop lying. Unfortunately, the converse is true – the better the understanding a child has between a lie and the truth, the more likely that child is to lie.

One of the biggest mistakes that parents make is to let a lie go. The most common reason for lying is to cover up misbehaviours and to get out of trouble. Parents who are aware of the lie usually correct the misbehaviour but not the lie used in an attempted cover-up. So while the child gets punished for wrong-doing, the lie goes unpunished. Ideally, both the lie and the misdemeanour must be addressed.

2. Lying is a developmental milestone.

The ability to recognise the truth, come up with a plausible reality and convince someone else that the lie is in fact the truth requires advanced cognitive development. It was found that children who started lying at two or three and who could control their lies by four or five performed better in academic tests. In other words, lying and intelligence is related.

Children initially begin lying to get out of trouble. As they grow older, their reasons for lying become more complex. Though they will still lie to get out of trouble, they also begin to lie as a coping mechanism. Generally an increase in lying is a sign that something has changed in a child’s life that troubles him. As they grow older and develop a sense of empathy, they may also lie to spare the feelings of their friends

3. How can parents manage lying?

Children are more likely to own up to a lie if they know they are not going to be punished for it. Many children associate lying with punishment. Ironically, that makes them lie even more – for self-protection. For this reason, the story about “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” is actually a poor fable for teaching children not to lie. At the end of the story, the boy was punished for his lying – that teaches children that lies are punished. To avoid further punishment, a child would rather maintain the lie than own up to it.

Conversely, the story about “George Washington and the Cherry Tree” in which little George confesses to his father that he chopped down the tree works better at promoting honesty. This is because the story ends with George’s father praising George for telling the truth: “George, I’m glad that you cut down that cherry tree after all. Hearing you tell the truth is better than if I had a thousand cherry trees.”

Another factor that must be taken into consideration is how the child perceives the parent’s reaction to the lie. Most children want to make their parents happy. If they believe that by admitting to the lie they will disappoint their parents, they are also more likely to maintain the lie than to own up to the truth. Parents who are able to convince their children that they would be happier to hear the truth are more likely to have children who own up to the lie.

In other words, to encourage a child to tell the truth, you need to:

- let them know they will not be punished for telling the truth.

- let them know that it will make you happy if they told the truth.

4. Parental influence.

Another reason why children lie is because they learn it from their parents. For instance, whenever they observe their parents lying, their parents are inadvertently teaching the children to lie. Even white lies, like pretending to like a gift out of politeness communicates to a child that lying is okay. Although such white lies might seem reasonable, a child eventually extrapolates the use of white lies to more serious instances with the belief that honesty creates conflict and that lying maintains harmony. So they lie to keep everyone happy.

Another type of lie is the kind where the truth is withheld. This is equivalent to the belief in the importance of not “ratting out a friend” at school. This begins early when parents try to get children to learn to resolve problems on their own. Children generally bring problems to a parent when they feel they have put up with as much as they can handle, yet when parents react in such a manner, they are inadvertently telling the child not to bring his problems to them. Over time, this reaction extends to other more serious occurrences such as shoplifting, cutting classes, vandalism, etc.

Although lying is an inevitable part of growing up, how parents are able to stop their children from continuing to lie depends very much on the way they behave and respond to the lies.

Chapter 5: The Search for Intelligent Life in Kindergarten

"Millions of kids are competing for seats in gifted programs and private schools. Admissions officers say it's an art: new science says they're wrong, 73% of the time."

This chapter reviews the ability to predict a child’s superior intelligence while in kindergarten. Many children are selected for gifted programs depending on how well they perform in a series of tests completed at a very young age. Unfortunately, the studies show that these tests are poor predictors for academic excellence in later life.

As parents, it is only natural to feel a sense of pride when our children excel. Especially when our children display precociousness at an early age, we tend to assume that they are gifted or at least brighter than the average child. And if our children display intelligent behaviours from an early age, it is naturally assumed that they will maintain this intellectual advantage over their peers as they continue to grow.

Not so.

According to the research, a child’s intellectual potential cannot be accurately gauged until they are in Grade 3. This is because brain development is variable – rather than falling into a bell curve, it follows sharp spikes in growth that are difficult to predict. It has also been shown that some children who later turned out to be gifted were below average in kindergarten – Einstein was one such child.

There are currently no tests available that can accurately predict how well a child will perform academically later in life. Any academic inclination demonstrated at such early ages merely suggest that the child has a good background.

There is a correlation between intelligence and the thickness of the cerebral cortex of the brain. Generally, the thicker the cerebral cortex, the better and the cerebral cortex peaks in thickness before the age of seven. In other words, the raw material for intelligence is already established by the age of seven.

However, research by Drs Giedd and Shaw from the National Institutes of Health found that while smart kids did have a bit thicker cortex at this age compared to the average child, the most intelligent kids had much thinner cortices early on. They did not reach their peak thickness until the age of 11 or 12 – the age at which IQ test authors claim that IQ tests become more reliable for testing a person’s IQ.

Conclusion: we need to give the late bloomers a second chance when it comes to pre-selection for gifted schools. Additionally, if you are a parent of a child who appears to be "slower" than his peers, you can now breathe a little easier.

Chapter 6: The Sibling Effect

"Freud was wrong. Shakespeare was right. Why siblings really fight."

There is a common misconception that being an only child is in some way detrimental to that child's social development. The theory is that being an only child deprives that child of the many interactions he would otherwise have with a sibling which would go a long way towards fostering the development of his social skills.

Unfortunately, this isn't the case. Children with siblings are no better off at getting along with other children compared to children without siblings.

What the studies have found about sibling relationships:

- Children treat their siblings with more negative and controlling statements than they do their friends. This is believed to be due to the fact that friends aren't bound to the relationship the way siblings are. Siblings will be there tomorrow no matter what, as a result, the relationship can be pushed to the limits beyond those of friendship.

- Sibling relationships don't change much over the years. The quality of the relationship during childhood remains the same over the years and into adulthood unless there has been a significant change in the family, e.g. divorce, death, or illness.

- Although siblings fight a lot, they can still have strong relationships. It is the net-positive result between the fights and the good times shared that determine the strength of the relationship. Siblings who ignored each other and had less fighting tended to stay cold and distant in the long term.

- To foster stronger relations between siblings it is important to help them learn to play together. Most activities that children are scheduled into during their lives are usually age-segregated. It is important to teach siblings how to overcome the age difference and find activities they can enjoy together.

- Being able to initiate play that both children enjoy can help prevent conflict.

- Negative relationships between siblings are being learned from the very books intended to foster stronger sibling relationships. Many of these stories begin by setting up a story of conflict which eventually gets resolved in a happy ending. Unfortunately, the books are also teaching the children negative behaviours and new ways to be cruel to their siblings.

- Despite the common belief that sibling rivalry stems from the loss of parental attention, studies show that it is more about claiming possession over toys. An overwhelming majority of fights were due to fights over toys.

- It is important to teach young children how to develop prosocial relationships with their siblings in order to get them to get along.

- Gender differences and the age gap between siblings is not a strong predictor in how well siblings get along.

- One of the best predictors for how well siblings get along is determined before the birth of the younger child - the quality of the older child's relationship with his best friend. Older siblings acquire their social skills from their relationships with other children and apply what they learn on their younger siblings.

- Shared fantasy play is another factor that helps foster stronger relationships because it requires emotional commitment and awareness of what the other child is doing.

- Older children need to have developed these positive social skills before the younger sibling arrives because there is usually no motivation to change when the younger sibling arrives. This is because siblings areprisoners who have been genetically sentenced to live together and have no time off for good behaviour.

The aim is to "transform children's relationships from sibship to something more akin to a real friendship. If kids enjoy one another's presence, then quarreling comes at a new cost. The penalty for fighting is no longer just a time-out, but the loss of a worthy opponent." It is the relationship that children have with other children that forces them to develop new skills rather than the relationship they have with their parents because getting what they want from a parent is easy. Other children don't care that they are hungry or that they have a bruised knee because chances are those children also have one too.

Chapter 7: The Science of Teen Rebellion

"Why, for adolescents, arguing with adults is a sign of respect, not disrespect - and arguing is constructive to the relationship, not destructive."

Although this chapter doesn't really relate to me now, it was still a very interesting read. It is also good preparation for me when my boys eventually become teenagers - although I often wish that they never grow up. What can I say? I'm enjoying them too much at this cute and adorable age.

All my life, my biggest fear of being a parent was the part when I'd have to deal with a teenager. I've seen kids go wrong and doing all the things every parent has nightmares about and I wonder what any parent can do to keep a teenager on the straight and narrow. Although I've never caused my parents any grief while I was a teenager, I do realise it is because I was lucky to have friends who were generally pretty well behaved. What if I had met the wrong crowd? Things might not have gone so well.

Now that I am a parent, what can I do to help my children stay out of trouble? That was what I hoped to find out from reading Chapter 7 from Nurture Shock - The Science of Teenage Rebellion. I'm afraid the scientific findings were none too comforting...

One of the general beliefs is that if you keep a teenager busy enough, they won't have time to get into trouble. It is often thought that adolescents turn to sex and drinking because they are bored. A study on teenagers revealed that:

- teenagers lie a lot more than parents would like to think.

- teenagers mostly lie about drinking, drug use and their sex lives.

- teenagers don't like emotional intrusiveness, e.g. "How serious is this relationship?"

- teenagers concoct outright lies 1/4 of the time to cover up the worst stuff.

- teenagers half the time they withhold information they know would upset their parents.

- the remaining 1/4 of the time they avoid the topic and hope their parents won't bring them up.

- 96% of the teenagers surveyed reported lying to their parents.

- even honours students and busy, overscheduled teenagers lie - no teenager is too busy to lie about something.

- the most common reason for lying was to protect their relationship with their parents - many teenagers wanted to avoid disappointing their parents.

A study on parents found that:

- many parents believed that the best way to remain informed is to be more permissive.

- parents feared being too strict might lead to outright rebellion.

The reality was:

- parents who were more permissive and failed to set rules did not learn more about their children's lives.

- teenagers who go wild are the ones who have permissive parents who don't set rules.

- lack of rules communicates to the teenagers that their parents don't really care about them.

- pushing a teenager into outright rebellion by having too many rules is a myth.

- teenagers dislike seeking help from parents because it is an admission that they are not mature enough to handle things on their own.

- teenagers need to have certain things in their lives that are "none of your business".

- the objection to parental authority peaks at 14-15, not at 18 as is most commonly thought, and resistance is stronger at 11 than it is at 18.

- oppressive parents with lots of psychological intrusion had the most obedient teenagers, however, those teenagers were also depressed.

The parents who were most consistent in enforcing rules were the ones that were most warm and had the most conversations with their children - they "set a few rules on the key spheres of influence and explained why the rules were there. They expect the child to obey them. Over life's other spheres, they supported the child's autonomy allowing her freedom to make her own decisions. The kids of these parents lied the least."

The hypothesis that most teenagers turned to drugs and drinking because they were bored was found to be true. Ironically, the feeling of boredom was not necessarily due to teenagers who had nothing to do. Even the busy teenagers who were involved in lots of activities reported feeling bored. Usually these were teenagers who were engaged in activities that their parents signed them up for. They lacked intrinsic motivation. It was also found that the more controlling parents were more likely to have "bored" teenagers.

Programs designed to teach teenagers to identify boredom and take action against it have not been found to be very successful. This is because teenagers require a lot more stimuli to derive pleasure compared to adults and young children. This difference in reaction was seen in a study where young children, teenagers and adults were required to play a pirate game with a reward of gold coins for success in the game. They could either get a single gold coin, a small stack of coins or a jackpot of gold. The pleasure centers in the young children lit up no matter how much gold they won. In adults, the pleasure centers lit up in proportion to the amount of gold won. In teenagers, only the jackpot of gold would create a big pleasure response. The small to medium rewards of gold would create a reaction that appeared as if they were disappointed. Teenagers were like drug addicts requiring large doses to create a large pleasure response.

It was also found that whenever teenagers experienced these large pleasure responses, their prefrontal cortex (which was responsible for weighing risks and consequences) experienced a diminished response. Therefore, when teenagers are "experiencing an emotionally-charged excitement", their brains are "handicapped in its ability to gauge risk and foresee consequences". Teenagers who are equally capable of evaluating risks as adults in abstract situations are no longer able to evaluate those same risks when experiencing exciting real life circumstances. This explains why teenagers are apt to engage in activities that are dangerous and inappropriate.

Teenagers who experienced the greatest spikes in the pleasure centers of their brains when they won the jackpot of gold in the pirate video game were most likely to state that certain risky behaviours (such as getting drunk, shooting fireworks, and vandalising property) felt like fun. The conclusion was that some teenagers are simply wired to take big risks. Surrounded by friends, teenagers are apt to take risks just for the thrill of it.

Yet, despite all these risks that teenagers are apt to take, there are some risks that terrify them: risks such as asking a girl to a dance and the fear of getting turned down, changing a hair style, wearing a new shirt - the possibility of embarrassment is a risk few teenagers are willing to take. In fact, teenagers would rather swim with sharks than face the possibility of embarrassment.

For teenagers, arguing is the opposite of lying. Families that had the most argument were the ones where teenagers told the truth most often. These teenagers that argued with their parents were the ones that told the truth. They respected their parents' right to lay down the rules but they would fight over what those rules were. Families with less arguments usually meant that the teenagers merely pretended to go along with their parents but did what they wanted to do anyway.

Ironically, while parents felt that arguments were destructive to their relationship, teenagers felt the contrary and believed that arguments strengthened their relationships. However, this was only the case where parents were willing to consider the teenager's arguments and be flexible with the rules if the arguments presented by the teenager were relevant. Therefore, while it is true that permissive parents had teenagers that lied and misbehaved the most, parents who were strict enforcers of the rules but were willing to make adjustments as necessary were the ones who were lied to the least. For instance, making allowances to change the curfew for a particular night in which a special event was taking place.

Last but not least, it has also been shown that the popular belief that the teenage years are the nightmare years of parenthood is actually false. The studies show traumatic adolescence to be the exception, not the norm.

Chapter 8: Can Self-Control be Taught?

"Developers of a new kind of preschool keep losing their grant money - the students are so successful they're no longer 'at-risk enough' to warrant further study. What's their secret?"

In answer to the question phrased - yes they can, but not in the way that we think. Most programs designed to influence children's thinking have been found to have very limited success, except for one program. The program is called “Tools of the Mind“. It was initially a test program but the results were so positive that it was deemed unethical to keep other students out of a program that was clearly superior in every way.

In one Tools of the Mind study, they took ten kindergarten teachers and randomly assigned them to either the regular school curriculum or the Tools of the Mind program. These teachers taught classrooms where a third to a half of the class were poor Hispanic students who were effectively a grade-level behind. After a year, the students in the Tools of the Mind program were almost a full grade-level ahead of the national standard. 97% of these children scored as proficient. Another study showed students from the Tools of the Mind program scoring markedly higher on seven out of eight measures, including vocabulary and IQ.

Even more impressive is the effect of Tools of the Mind on child behaviour. Teachers teaching the regular classes often reported extremely disruptive behaviour almost every day. These include behaviours such kicking the teacher, biting another student, cursing, throwing a chair, etc. In the Tools of the Mind classrooms, such behaviours never occurred.

In other words, Tools of the Mind not only produces brighter children who are classified as gifted more often, but it also produces better behaved children.

Why does Tools of the Mind work so well

In order to learn a child needs to be able to concentrate for a period of time. In order to be able to concentrate, children need to learn how to avoid distractions. Essentially, what prevents a child from being able to concentrate are distractions. Children with a lack of focus also lack the ability to concentrate on an activity for any extended period of time. What Tools of the Mind focuses on is how to help a child avoid distractions.

For instance, a Russian study asked a group of students to stand still as long as possible. These students lasted two minutes. A second group of students were told to pretend they were soldiers on guard at a post and they managed to stand still for eleven minutes.

The philosophy behind Tools of the Mind believes that play is an essential part of learning for children. The problem with today’s educational system is that the pressure for academic achievement has increased and as a result, the amount of play time children are allowed is reduced. Tools of the Mind believe that the basic developmental building blocks that are necessary for academic success are learned during play time.

The ability to learn abstract thinking occurs during play. High-order thinking, such as self-reflection – the internal dialogue we often have within our minds as we weigh out opposing alternatives – are also encouraged with Tools of the Mind. Adults can perform this task silently in their heads, but young children learn how to do this through first voicing it out loud by talking to themselves as they run through their activities. The ability to perform high-order thinking helps children avoid distraction and keeps them from reacting impulsively during class.

Tools of the Mind not only teaches children how to avoid distraction, but it help them become self-organised and self-directed.

Aside from the visual effects of Tools of the Mind on child development, the theory is also supported by neuroscience. Tools of the Mind helps a child develop “executive function” in the prefrontal cortex. In other words, it helps a child plan, predict, control impulses, persist through trouble, and orchestrate thoughts to fulfill a goal. Although executive function represents very adult attributes, it has been shown that executive function begins as early as preschool.

One of the ways Tools of the Mind helps a child develop this part of the brain is through the activity of planning time management and setting weekly goals. This helps to wire up the part of the brain that is responsible for maintaining concentration and setting goals.

Part of the Tools of the Mind curriculum requires children to check and score their own work against answer sheets. Children are also paired with another child to cross-check each other’s work. This helps the child develop an awareness of how well he’s doing. Being aware of how well he’s doing is part of a loop that helps him recognise when he is not doing well and needs to concentrate harder. In order to do this, a child’s “cognitive control” needs to be switched on.

Cognitive control is responsible not only for avoiding external distractions but it also internal distractions, such as the thought, “I can’t do this.” Cognitive control is used to manipulate information in the mind, such as planning chess moves in advance. Cognitive control is also responsible for helping children pick the correct multiple choice answer. Multiple choice questions often throw in an answer that is intended to be a distraction. Children with poor cognitive control are often tricked into selecting this answer.

The Tools of the Mind program helps children to be proactive whereas most children generally react to situations. Such proactive responses are akin to telling yourself ahead of time what you are going to do so that decisions can be made instantly and correctly. Tools of the Mind also allow children to choose their own work. By allowing children to choose their own work, they are more likely to choose what they are motivated to do. By virtue of the fact that the motivated brain works more effectively, motivated children learn more.

Finally, the reason why Tools of the Mind is such an important program is because it prepares children for real life. Real life is full of distractions. It will not be like an IQ test which is performed in a quiet, controlled environment. Tools of the Mind teaches children to focus and shut out distractions.

Chapter 9: Plays Well with Others

"Why modern involved parenting has failed to produce a generation of angels"

What makes a child more aggressive and what can we do to help them learn to get along with other children? It has always been the belief that children who watch violent shows (e.g. Star Wars, Power Rangers) are likely to be more aggressive, while children who watch educational shows (e.g. Clifford the Big Red Dog) would not only be less aggressive but more pro-social - being able to share, be helpful, etc.

The studies revealed some interesting surprises. While it was true that children who watched less violent media were not as aggressive physically, they found that children who watched educational shows designed to teach children how to be more pro-social actually ended up making them more relationally aggressive. Children who watched more of these "educational" shows ended up being more bossy, controlling and manipulative.

How did these educational programs get it so wrong? Upon further examination, it was found to be due to the fact that many of these shows spent the bulk of the episode setting up the conflict and too little time resolving the conflict. Young children with poor concentration spans often only see the conflict but failed to make the connection to the "moral" of the story at the end of the show. These children end up modeling the "bad behaviour" instead of learning not to do it.

What was shocking was that the more "educational" shows children watched, the crueler they were to their classmates. The correlation between the "educational" shows and relational aggression was even stronger than the correlation between "violent" media and physical aggression. Not only were "educational" shows failing to produce the desired effect on children, it was even worse than allowing children to watch violent TV shows.

Another commonly misguided belief is that aggressive children were from "bad homes". Bronson and Merryman found that it isn't quite as simple as that. In fact, many of the solutions being implemented to manage aggressiveness in children are actually backfiring.

Even in the best of homes there is bound to be conflict between parents - whether it is simply bickering over who forgot to pick up the dry-cleaning or pay the bills. Children are highly attuned to such conflicts, however, it isn't necessarily as bad as we think. Research revealed that children who were able to witness the resolution of the conflict were often better off than those who were "spared" the conflict when parents took up the argument in another room. Even arguments that occur entirely away from the children fail to escape their notice - although the children do not know the specifics, they are aware of the conflict.

What is important to a child is not the conflict but that the conflict was resolved. Being able to witness the resolution of the conflict not only improves the child's emotional security, but it also helps to improve the child's pro-social behaviour in school - so long as the arguments between parents do not escalate, insults are avoided, and the conflict is resolved with affection.

What about negative interactions between peers? It appears that being too protective can also have a negative effect. A policy for "zero tolerance" (toward bullying at school) found that it had a negative effect on children. Although bullying should not be accepted as a normal part of childhood, implementing a policy for "zero tolerance" is not the solution. This is because children are young and they make mistakes. Inflicting severe, automatic responses for these mistakes erodes their trust in authority figures. The children end up being more fearful of "accidentally" breaking the rules which increases their anxiety.

There is a complex relationship regarding bullying among children. Ironically, most of the meanness, cruelty and torment are not inflicted by the "bad" kids or those most commonly labeled as bullies. They are mostly inflicted by the popular, well-liked, and admired children. Contrary to the idea that non-aggressive children were simply being "good" children, it was theorised that these children merely lacked the savvy and confidence to assert themselves as often.

Aggressiveness is used to assert dominance to gain control and protect status. It is not necessarily the mark of a child who lack social skills but the contrary - it often requires a child to be extremely sensitive to his/her peers. To be able to attack in a subtle and strategic way, the child has to be socially intelligent - the child needs to know just the right buttons to push to drive his/her opponent crazy.

So if the popular kids are more aggressive, then why are they admired and held in such high regard? Because they are seen as being independent and older because of their willingness to defy authority. Children who always conform to adult expectations are often seen as wimps. However, this doesn't make the popular children worse. These children not only use antisocial tactics for controlling their peers, they are adept at prosocial skills. They cleverly deal the right balance of power (kindness and cruelty) to achieve what they want.

What are the conclusions?

1. Decreasing violent TV programs and increasing "educational" ones have merely refined a child's skills in relational aggression.

2. Removing marital arguments with the intention of reducing a child's exposure to parental conflicts deprives them of the chance to witness conflict resolution between two individuals who love each other.

3. Peer aggression alone is not an accurate measure of social development. By lumping children of a similar age together, we are forcing them to socialise themselves. We have created an environment that drives children to seek peer status and social ranking and this sometimes involves the use of aggression.

Chapter 10: Why Hannah Talks and Alyssa Doesn't

"Despite scientists' admonitions, parents still spend billions every year on gimmicks and videos, hoping to jump-start infants' language skills. What's the right way to accomplish this goal?

Contrary to what you may believe, the reason why a child learns to speak earlier while another does not is not due to early exposure to educational DVDs like Baby Einstein. According to Bronson and Merryman, you would be better off letting your child watch adult shows with live actors because they would learn more from these. This is because children need to see a person’s face as she talks. The reason this makes all the difference between whether a baby is able to pick up the language or not is because babies learn to decipher speech partly by lip-reading – they need to watch how people move their lips and mouths to make sounds. Babies need to learn when one word ends and another begins before they can understand what the words mean.

Baby DVDs like Baby Einstein don’t help children learn to communicate earlier because they show a series of images with a disconnected voice-over. So what about the DVDs that show human faces talking? Well, apparently they are better but nothing beats a real live person because a live person responds directly to the baby. A live person will notice baby’s gaze and is able to talk about what baby is looking at. A live person will also hear baby’s responses and react directly to the sounds made by baby. A television program can’t do either of these.

Another commonly recommended tactic to employ if you want your child to be a precocious speaker is to talk to your baby and expose your baby to the language of the world around him as much as possible. The more language your baby is exposed to, the faster he will pick up the ability to speak. This was found to be true based on a study showing a direct correlation between children from higher socio-economic backgrounds who were exposed to more words per hour compared to infants from welfare homes. New research reveals that this isn’t the only thing that is important. What is also important is how caregivers respond to the baby.

There are two types of responses to factor into the caregiver's reaction to the baby – physical and vocal. Non-vocal responses, such as a touch or a hug, can also have an enormous impact on a baby’s language development, indicating that infants aren’t just mimicking what they hear from their parents. Physical responses from parents can also illicit an increased frequency of babbling and even the maturity of the babbling. It is like a reward to the baby for making the sound and it encourages the baby to make more similar sounds. Vocal responses encourage the child to mimic. For instance, parents making vowel sounds encourage more vowel sounds from the baby.

Although attentive and responsive parenting is beneficial for accelerating a baby's language acquisition, it is also important not to overdo it. Babies need down time to absorb what they have learned. Excessive responses from parents prevent babies from consolidating new materials learned. The other downside of responding at a high level throughout the day is that it reduces the power of the reward – intermittent rewards are often more motivating than constant rewards.

Another factor to consider is the type of sounds that are reinforced. Ideally, caregivers should respond to increasingly mature sounds so that the baby progresses from meaningless babbling to making more meaningful sounds that will later contribute towards real speech. Some parents, in their eagerness to increase the response rate from their babies, may make the mistake of reinforcing less resonant sounds. By making it too easy for baby to get attention, they inadvertently slow development.

There are two other mistakes parents can make when helping a baby to develop language skills:

1. When object labeling, it is important to follow the child’s attention. Some parents make the mistake of intruding by trying to direct a child’s attention. It is important to allow the child to show some interest in the object first.

2. When object labeling, some parents ignore the child’s cues and take their cues from what they think the child is trying to say. For instance, a baby might be holding a spoon and saying, “beh”, but instead of correctly identifying the spoon as a spoon, the adult thinks the baby is trying to say “bottle” and responds with, “Bottle? You want your bottle? I’ll go get your bottle.” This is called criss-crossed labeling and it can have a strong negative effect on language acquisition.

For parents interested in reinforcing language acquisition, here are some things they can do:

1. Use parentese – the sing song voice that parents instinctively use to talk to babies makes it easier for babies to pick up language.

2. Use motionese – when talking about an object, shaking, twisting, and moving it around helps to draw the baby’s attention to the object. This is important for infants up to 15 months only. Beyond this age, motionese is no longer necessary.

3. Allow baby to listen to multiple speakers – babies pick up language faster when they hear it spoken by different individuals, compared to hearing it just from one person. This helps them learn phonics despite the differences in pitch and speed as different individuals speak differently.