Déjà Vu

It's happened to all of us; you stroll into a room, or meet someone for the first time, and a crashing wave of familiarity forces you to stop and look around in bewilderment. "Haven't we met before?" You might breathlessly inquire, reaching to shake your associate's hand and flinching as you watch the situation replay in your mind. Why do we experience moments of that mental phenomenon known as déjà vu? Are we all slightly clairvoyant or just victims of subconscious hypnotism?

Introduction

For many, déjà vu is a weird, disconcerting experience; for others, it may be thrilling or even spiritual. Occurring at random and lasting anywhere from a few seconds to a few minutes, one might have the distinct sensation of stumbling upon one's future.

The widely-accepted scientific definition of déjà vu (literally French for "already seen"), as it was originally stated in 1983 by psychiatrist Vernon Neppe, is "any subjectively inappropriate impression of familiarity of the present experience with an undefined past." However, what inspires this inappropriate familiarity remains a mystery. Beyond the empirical realm of science, various religions and parapsychologists have offered up their own interpretations, claiming that déjà vu is an indicator of clairvoyance, past lives, or parallel dimensions. Unfortunately, because those "really weird feelings" are difficult (if not impossible) to scientifically reproduce, researchers have struggled to understand their roots and affects on the brain.

Memory and other Mental Tricks

When we recall past events, we tend to remember flashes of images and snippets of sound in an order that is far from lineal or chronological. We recall bits of conversation, the taste of a steak dinner, the persistent ringing of our mobile phones, yet we often cannot recall the exact details of all that has happened. One memory sparks another, until we find ourselves sifting though a tangled network of cognitive associations. Now for the fun part: How do we know that our memories are accurate, or even real? What if we've just created a bunch of false-memories? How can we trust ourselves to remember what happens in the past?

The answer is deceptively simple, if it "feels" or "seems" wrong, it probably is. Like most other physical systems, we only become aware of our memory when something fails or we actively concentrate on its mechanics. Contrary to what we'd all like to think, memory is not some internal filing system where we can search for important details by "subject," "date filed," or cross-referencing. In the 1970s, cognitive psychologist Endel Tulving first proposed a distinction between episodic memories - the recollection of our own experiences (like traveling with friends to San Francisco) - and semantic ones, which involve empirical facts and other data (like remembering that "Fisherman's Wharf" is located near San Francisco Bay).

When we summon our episodic memories, Tulving states, we don't just call up the basic information. Rather, we mentally recreate the events as we see them. When we experience that feeling of familiarity evoked by our memories, we feel validated in our recollection of events. "Remembering," Tulving summarized in 1983, "is mental time travel, a sort of reliving of something that happened in the past."

The History of Reliving History

Writers and poets have long been fascinated by the seemingly unearthly abilities of the mind; St. Augustine wrote of "falsae memoriae" in A.D. 400, Sir Walter Scott described "a sense of pre-existence," and Hawthorne, Dickens, Tolstoy and Proust all have explored it in their prose.

Amongst members of the scientific community, déjà vu has been called both "paramnesia" and "phantasms of memory." The first research was completed in 1890s France, when prominent psychologists debated the unusual case of Louis, a 34-year-old who had recovered from cerebral malaria, and "showed 'the first symptoms characteristic of déjà vu' when he started claiming that he could recognize certain newspaper articles that he said he had read previously." Later in the 20th century during the rise of behaviorism and Freud, déjà vu was said to result when present situations resembled one's suppressed fantasies. However, even the famed Austrian doctor declared the phenomenon too confusing to be properly investigated.

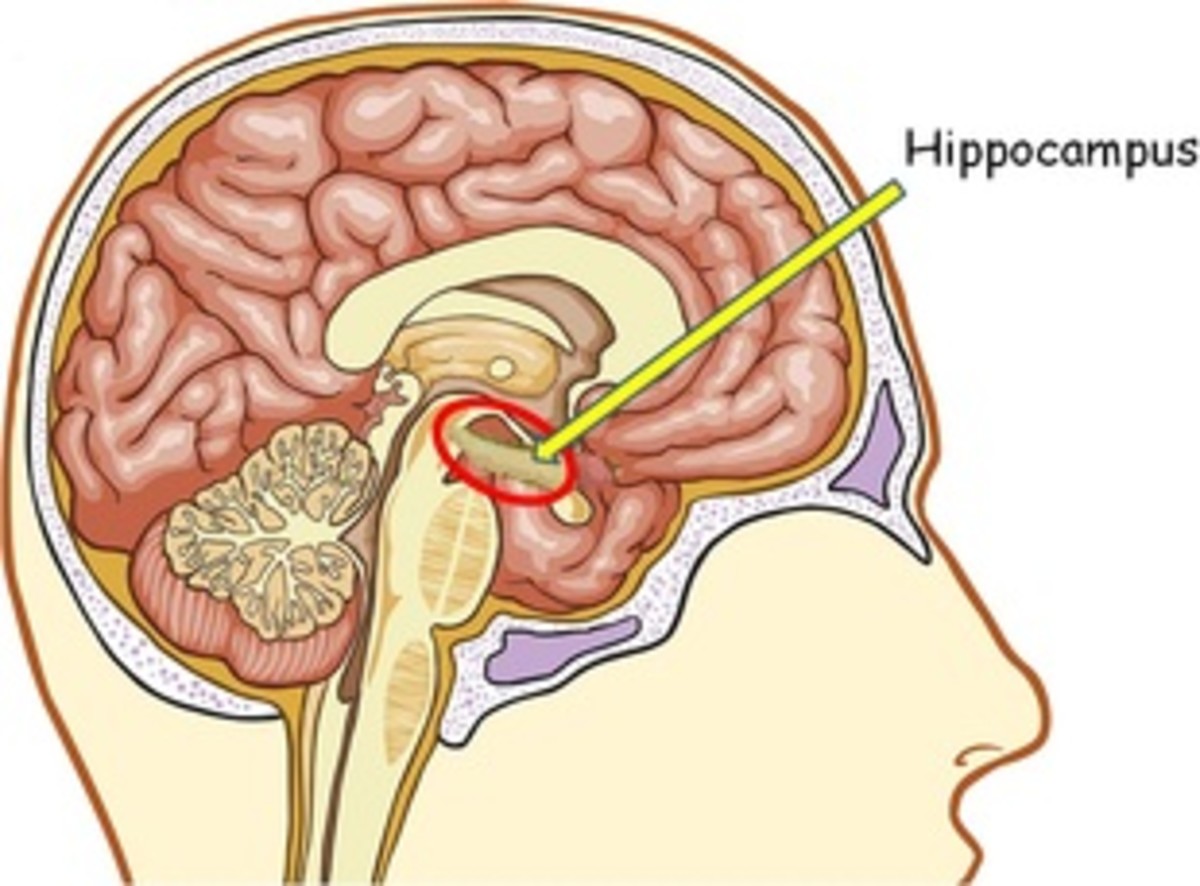

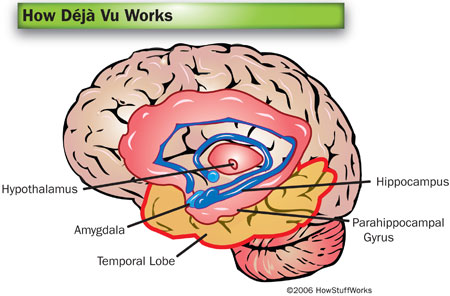

However, the mystery may yet have a solution, thanks to a team of neuroscientists at MIT's Picower Institute for Learning and Memory. Researcher Thomas McHugh and several colleagues have uncovered a specific memory circuit in the brains of mice that is probably the cause of dèja vu's weird sensations. While McHugh and his team were trying to untangle the neurological circuitry of the hippocampus, a region of the brain where new memories are formed, they found that the pattern-separation brain circuit "misfires," and causes a new experience that's merely similar to an older one to seem identical. Therefore, that eerie feeling that so often accompanies déjà vu "comes from a conflict between two parts of the brain... The neocortex is aware of the fact that you've never been in a situation before. The hippocampus is telling you that, yes, you have."

The Three Modern Models of Déjà vu

Victorian-era British psychologist Sir James Crichton-Browne suggested that dèja vu is caused by a "trifling and transitory" brain disorder, "like cramp in a few fibers of muscle." Here are three of the latest attempts to explain the phenomenon:

1.) Spontaneous neural activity in the parahippocampal gyrus: The brain suffers a small seizure in the parahippocampal system, which is associated with spatial processing and our sense of familiarity.

2.) Slowdown in the secondary visual pathway: Some researchers believe that a dèja vu experience occurs when signals on the secondary pathway move too slowly, and the brain interprets this second wave of data as a separate experience.

3.) Divided Attention/ "The Cell Phone Theory" (as proposed by Dr. Alan Brown, Duke University): Imagine that you drive through an unfamiliar town but aren't really paying attention because you are talking on your mobile. If you then drive back down the same streets a few moments later, while being focused on the scenery, you're likely to experience dèja vu, because the visual information is being consciously processed in the hippocampus but feels "old" because the images from your earlier drive still linger in the short-term memory.

Whatever the explanation, be it scientific or spiritual, déjà vu will continue to delight and puzzle the minds of those who encounter it. So you see, while reading Hubpages, you learn something new everyday... unless, of course, you've already seen this before?