History of April Fool's Day

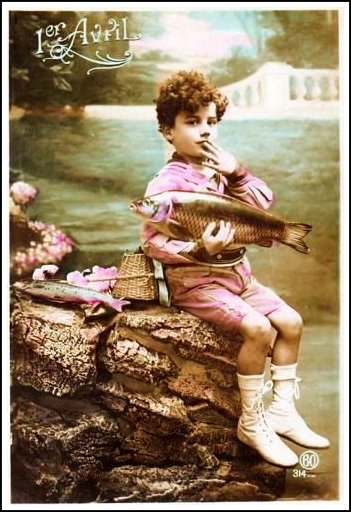

"April Fish" Post Card

It’s not certain when or how April Fool’s Day came about. The most popular theory is France changed its calendar in the late 1500s, which had the New Year beginning in late March or early April, to coincide with the Roman or Gregorian calendar. But, in that day news traveled slowly and those living in outlying rural areas continued celebrating New Year’s as usual. Thus, these clueless, country bumpkins were called "April fool's" by their more sophisticated contemporaries, according to the legend.

Those failing to change their habit had jokes played on them. Pranksters would stick a paper fish to their backs and labeled “Poisson d'Avril,” or April Fish, the French term for April Fool's. However, not all historians agree with this theory. Some scholars hold this theory to be wrong since the French celebrated New Year’s on Easter day.

Many French regions had been using Easter as the start of the new year. However, that caused much confusion since that date was tied to the lunar cycle and changed from one year to the next and sometimes occurred twice a year. Others believe April Fools' Day evolved from ancient European spring festivals of renewal, in which pranks were common.

Britain didn’t change its calendar year to January 1 until 1752, by which time April Fool's Day was already well established. So, confusion about the calendar change was most likely not responsible for the custom in Britain.

There have been many vague written references to the celebration over the centuries, hardly any proving conclusively when or where it began. The Flemish writer, Eduard De Dene for example, wrote a comical poem in 1539 about an aristocrat who sends a servant on repeated, ludicrous errands on April 1st. Eventually the servant catches on and in the closing line of each stanza he remarks, "I am afraid... that you are trying to make me run a fool's errand. Being sent on a “fool’s errand” is still a popular metaphor to this day.

Another example of vague references occurs in a 1632 legend concerning the Duke of Lorraine. The tale revolves around the Duke and his wife being imprisoned at Nantes. They escaped on April 1, by disguising themselves as peasants. A vigilant citizen happened to spot the escape attempt and notified the guards. But they believed the warning was nothing more than an April Fool's Day joke and the royal prisoners waltzed on out the front gate unmolested.

The April 2, 1698 edition of a British newspaper reported about a popular prank of the day. It referred to several gullible people being sent to the Tower of London the day before to witness "The Washing of the Lions." Of course, no such event existed. It became an annual April Fool's Day tradition with reports of it occurring as late as the mid 1800s.

In late March Romans were known to celebrate Hilaria, a festival honoring the resurrection of Attis, son of the GreatMother Cybele. The event was chronicled with rejoicing and wearing disguises. Some believe the name Hilaria is the origin of the modern day term, hilarious. And there are numerous other like references.

Even today’s usually straight laced, educated academics aren’t above pulling a prank or two on this day of revelry. One professor of American humor at Boston University had the last laugh when he presented his version of the holiday’s origin to an Associated Press reporter in 1983.

According to the professor, in the third and fourth centuries A.D. court jesters had convinced the Roman ruler Constantine to let an appointed jester to be king for one day. This jester-king decreed the date would forever be a day of absurdity. When the Associated Press became aware he was pulling their leg they were not amused.

Although traditional pranks and tom foolery are still hallmarks of this auspicious day more culturally wry humor has recently made its debut in the form of the annual Ig Noble Prize awards, first presented in 1991. Although not presented on April Fool’s Day, many nominees are recognized for acts perpetrated then. Ten prizes are awarded in March each year in various categories for discoveries "that cannot, or should not, be reproduced,” and are considered a form of veiled criticism or gentle satire. Most often they are given for scientific articles lampooning some ridiculous theory, discovery or statement and are presented by genuine Nobel laureates. Such as the declaration, black holes fulfill all scientific criteria for being the location of hell, or belief food dropped on the floor and picked up within five seconds will not become contaminated.

The name is a play on the word ignoble meaning characterized by baseness, lowness, or meanness and the name "Nobel" after Alfred Nobel. For instance, the 2007 award for medicine went to a team who published an article on sword swallowing and its side effects. It was published in the esteemed British Medical Journal, no less. The ceremonies are usually concluded with the statement "If you didn't win a prize…and especially if you did…better luck next year!"

The news media has even gotten into the spirit.On April 1, 1957 the British television program Panorama broadcast a three-minute segment about the bumper spaghetti crop in southern Switzerland being attributed both to an unseasonably mild winter and eradication of the spaghetti weevil.

Richard Dimbleby, a well respected, serious minded news anchor, narrated the video clip showing a Swiss family harvesting pasta off spaghetti trees. Dimbleby ended the story with the statement, “For those who love this dish, there’s nothing like real, home-grown spaghetti.” The hoax had hundreds phoning the BBC requesting information on how to grow spaghetti trees. They were given this sage advice. “Place a sprig of spaghetti in a tin of tomato sauce and hope for the best.”

Since then the BBC has been known to air other similar fake stories on April Fool’s day, such as the advent of "smell-o-vision"; left handed hamburgers; replacing the face of Big Ben with a digital clock. And according to expert astronomers, an unusual alignment of planets would weaken Earth's gravitation field and allow people to jump to Olympic record setting heights.

Although when and where the celebration may have originated isn't known, it’s sure to continue until time immemorial.