- HubPages»

- Travel and Places»

- Visiting Africa»

- Travel to Eastern Africa

A visit to a Masai Village

Read Fenella's African adventures!

Read more about the Masai

We should be grateful for what we've got

As my class are currently doing a unit of inquiry on Law and Order which covers rules and government systems and such-like, I thought it would be a great idea to look at Tribal Law in Tanzania. Specifically, Masai Law. Our school has a community and service activity called Hard Labour. A few weekends a year, older children volunteer to spend a weekend building something like a classroom for a school in a MasaiVillage. When I mentioned my idea about going out to a Masai village, the Community and Services Coordinator immediately suggested the village where the Hard Labour team had built a one-classroomed school. Apparently, the school had a good relationship with the chief.

Getting hold of the chief proved to be quite difficult, as there’s no electricity or phone lines in the village, dropping him a quick email was out of the question. His main wife does come into town from time to time to sell Masai beadwork. So, we hatched a plan to send one of the school drivers with a letter written in Kiswahili to give to someone who might know someone who might see her and pass on the letter. It all sounded quite vague and I wasn’t too sure it would ever happen. However, over the weekend, the wife contacted the Community and Services Coordinator who contacted me to say we were most welcome and we could go. It was a bit like playing that telephone game we played as children! Anyway, Monday morning, I quickly drafted a letter to the parents, booked the school truck, as the bus would not be able to drive on those roads, and organised the children to bring in foodstuffs like flour and rice that we could give the Chief as a thank you and some kind of a tribute. Thursday was going to be the day for the trip.

It poured with rain Wednesday, and I was terrified that would ruin our travel plans for the Thursday, especially if the rain decided to hang around for a bit Thursday. Luckily, I was told that even if it pours with rain here in Moshi, it will be dry as a bone in the Masai lands as it never rains there. Thursday morning and the gods were smiling down at us. Slightly overcast, decidedly chilly, but no rain. The truck had a roof, but open sides, which meant if it was raining, they’d have had to pull the tarpaulins down the sides, cover us completely, and I’d have to spend close on two hours sitting on the back of a dark, stuffy truck with 20 over-excited children. Not something to look forward to and a sure dampener to the spirits.

To get to the village, we drove through Moshi town and then through the miles and miles of sugar cane fields belonging to a huge sugar company. Although dirt, the road was okay, not too dusty in the back of the truck, but very noisy as the kids sang the same bus trip songs you hear all over the world. As we left the sugar cane fields, not only did the landscape start to change to a much drier one, but the road started to deteriorate, until it was no longer a road but a beaten track. We bounced around, bumped our heads on the roof, narrowly missed being decapitated by errant thorn tree branches which sometimes managed to find their way inside the truck, and generally got shaken around. However, despite a few bumps and bruises, everybody escaped serious injury and the kids all took it in their stride. One of my parents works for the Seattle Times and is on a year’s sabbatical in Tanzania with her kids and husband, and she brought along her really expensive Nikon with it’s ultra-long lens, which put my little Samsung to shame! We passed the odd few trucks, almost scraping sides on the narrow path, and ate each other’s dust. We drove over a rickety wooden bridge spanned across a very scenic river, with crocodiles basking in the sunlight on the river banks. Each little village we drove through, became more rustic looking than the one before it. One of the villages had no electricity, a combination of traditional huts and brick one-roomed houses, but the centrepiece of the village was a lapa with its thatched roof and a pool table inside! In the middle of the African bush, a pool table! But from then on, Western influence on the villages became less and less. The riverbeds we passed over were dry and dusty. The road, such as it was, disappeared completely, and we just drove through bush and dry ground. The chill in the air we had felt in Moshi was gone, and we all shed our warm tops as the sun’s warmth started to bake us.

Finally, we arrived at the village, and I was very relieved to see the Chief standing next to the bar/shop/post office. We had tried to call the cell number his wife had given but hadn’t been able to get a response. I’d sent a text message in Kiswahili, but no reply. So, basically we had taken a bit of a flyer doing the trip, but we’d been assured that the Chief would probably be there as it’s not like he goes anywhere. Before you get excited hearing they had a bar/shop/post office, don’t. It was basically an empty building with chairs around for people to sit outside. The Chief was nothing like the superbly handsome tall muscular specimens of Masai manhood I had perchance noticed in Moshi when I was getting my Pajero fixed. He was old, probably pushing sixty I’d say, and he walked funny with his old bandy legs. He had the most amazing teeth that protruded and jutted out horizontally at the same time. Very un-chieflike in appearance, no feathers or lion skin, just his tartan Masai cloth wrapped around him. His eldest son quickly appeared, with the same protruding teeth, so genetics must be strong, but luckily his teeth were vertical. We were directed to a big tree where the Chief had his chief-seat and a few other chairs around him for his son and wives.

Women, many still young girls, carrying babies on their backs, young children and older women all started emerging from the huts and joined us under the tree, and soon we had quite a crowd. Little boys chased a herd of what looked like quite recently born goat kids, and under a tree, a donkey was tethered. The donkey is used to carry water which is fetched from the big crocodile river we had passed many kilometres away. My teaching assistant, Catherine, acted as the translator and asked the Chief all the questions we had come up with. Some of his answers were surprising, as there are many myths and misconceptions about the Masai. His name is Chifu Lazara and he has three wives and sixteen children. Polygamy is a part of their culture. Girls get married between the ages of 12 and 14. They are too old after that to get married he said. Boys are allowed to get married from the age of 15. If a boy or man wants to get married, he has to pay about 8 cows to the bride’s father. So, it’s good to have a lot of daughters, as you can increase your cattle herd nicely! According to Chifu Lazara, he is chief of the boma which is made up of different clans. Each clan has a sort of a mini-chief, which in other African tribes would probably be referred to as a headman. When we tried to press him to find out exactly what a boma was, all he said it was people who shared the same ancestors. When asked how many people in a boma, he said too many to count. So, I take it that Chifu Lazara is like a paramount chief. He said that they follow Tanzanian laws that suit them and do vote in Tanzanian elections, however, they also have some of their own laws, mostly to do with how they have to look after their cattle. If someone steals or breaks one of the laws, the Chifu decides on the punishment, which is usually a fine of cows, or if a child, a beating with a nice whippy stick. When we asked how one becomes a chief, Chifu Lazara replied that when a chief feels he’s too old to make good decisions for his people, he stands down and his eldest son takes over the chieftainship. When asked what happens if the chief doesn’t have any sons, Chifu Lazara laughed so much, he lost his balance and nearly fell off his chair. He said that of course the chief would have sons, as if his wives weren’t giving him sons, he would just keep taking more wives until he found one who could make sons. I decided not to ask what would happen in the case of male infertility. I wisely thought it was best not to go there.

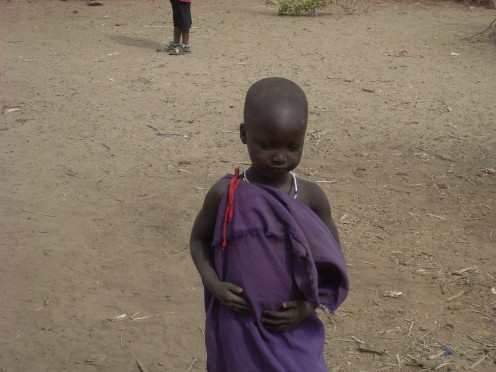

The village was very poor and the people are literally starving. I felt bad that we hadn’t collected more than we did for them. Another class is visiting next week, so we’ll be collecting more food to send with them. But this is just a short fix. What will happen to them longterm? It hasn’t rained for so long in their area, the cattle are dying. All the younger men and boys were out with the cattle, which are quite far from the village as there is no grazing near the village at all. One wonders why the people still choose to live in a remote area with no grazing. The school that our older students built last year hasn’t been used since the beginning of July. The government didn’t pay the teacher, so the teacher left. They say that there doesn’t seem to be much hope of getting another teacher. The children are painfully thin and many have visible ringworm and patches of missing hair, that I saw before with the Bushmen I visited in Botswana, a sign of poor nutrition. The children just wear a scrap of cloth and nothing underneath. Very few have western clothes. No toys, no books, no food.

My class has decided by themselves, that they want to take action and raise money to buy some food, so we’re going to organise a Readathon, where they’ll get sponsorship for each page they read. But, at the risk of sounding cynical, it’ll be a small plug in a big hole. Despite the poverty, when we had finished and presented our box of foodstuffs, the masai women surrounded our group and gave us Masai beadwork jewellery. I had a woman putting a pen in a bead holder around my neck, another put a beautiful necklace with a beaded fish around my neck. Then, I felt my ears being tugged on. Masai women were checking to see whether or not I had pierced ears, and they put earrings in my ears. We were quite overcome by their kindness. Chifu Lazara’s eldest son stopped us as we were heading back to the truck, and told us that their goats were dying from tick bite fever, as they don’t have money to buy some dip for the goats. I promised to look into it, which I’ll do today.

Yesterday, my teaching assistant told me that last year there was friction between Chifu Lazara and Mama Taimai his first wife. As Masai girls get married so young, they don’t go to school, and she decided that she wanted two of her daughter to get a high school education, which is completely against Masai tradition. Chifu was very angry as he saw sending the girls to school as a loss of income, as if they got married he’d get 16 more head of cattle. However, Mama Tamai stuck to her guns and insisted and it seems she won the battle. Two of her daughters are at a boarding school in Kenya. I’m not sure how they pay for it. Hopefully, the girls will come back and educate the other children, maybe use the little school that was built. I have to say, that it is the women who generate the cash for buying everyday supplies. The men just sit around under the trees and laze around. The younger men and boys watch the cattle graze. The women plant vegetables, cook, look after children and make traditional Masai beadwork to sell to tourists. That money is used to buy basic supplies. We gave three Masai women, including Mama Tamai, a lift into town to sell their beadwork to tourists, saving them the $2 each in taxi fares on one of the trucks that ride back and forth into the Masai lands. Tourism is down, so they struggle to sell their bead necklaces. Not only do they have to sell enough to pay for their fare back to the village, but they have to be able to generate enough money to buy food for the rest of the village. They said they’ll be staying in town for about three days, trying to sell their handicrafts. Meanwhile, Chifu Lazara, the other villagers and the starving children wait patiently for the three women to return with food. This trip to the Masai Village, was definitely a National Geographic-type experience. You can follow my blog to find out more about my crazy life and adventures.