Avatars of the Virgin of Guadalupe

The Virgin Mary, in her various autonyms: Our Lady of Mercy, Our Lady of the Rosary, Our Lady of the Remedies, Our Lady of the Purification, the crowned Madonna, Our Lady of the Sorrows, Our Lady of the Annunciation, Our Lady of the Assumption and Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, upholds a preeminent place in the history of Christian saints in Latin America. But among all those, the autonym Virgen de la Guadalupe occupies a higher estimation among Mexicans and other Latin American Catholic believers.

Culturally, the Virgen de la Guadalupe (the "Patron of Mexico" and "Empress of the Americas") is viewed as a protective and nurturing mother, an embodiment of life and hope in times of repression and adversity, and even incarnates the hybridized nature (mestizaje) of Mexican (and Latin American) people and culture. Her image helps to bring and keep a national cohesion in face of the cultural, social and political diversity of the nation. Hence, the Virgen de la Guadalupe have been inextricably intertwined in the religious, cultural and political narratives of Mexico's national identity and endeavors.

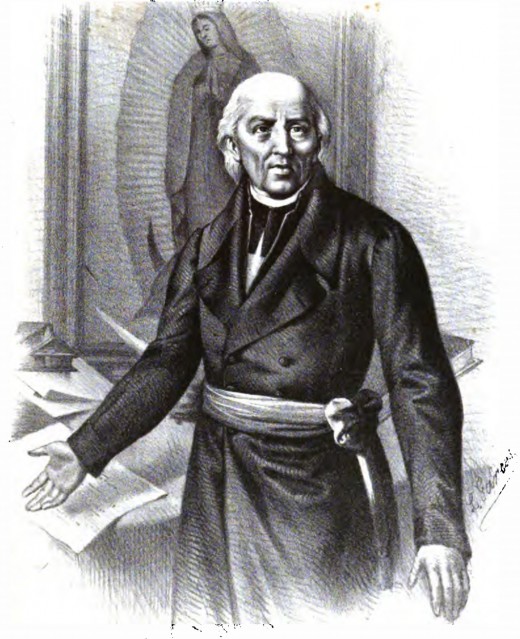

For instance, on September 1810, with a proclamation known as the Grito de Dolores, Fray Miguel Hidalgo a Catholic priest of progressive ideas, declared Mexican independence. He addressed the people in front of his church and, invoking the name of the Virgen de la Guadalupe, encouraged them to revolt:

My children: a new dispensation comes to us today. Will you receive it? Will you free yourselves? Will you recover the lands stolen three hundred years ago from your forefathers by the hated Spaniards? We must act at once… Will you defend your religion and your rights as true patriots? Long live our Lady of Guadalupe! Death to bad government! Death to the gachupines!

The Virgen became a symbol of "Mexican', because she was depicted as a mixture of the indigenous people and the Spaniards; she was as “Mestiza”. The true “Mexican” -neither Spanish nor indigenous.

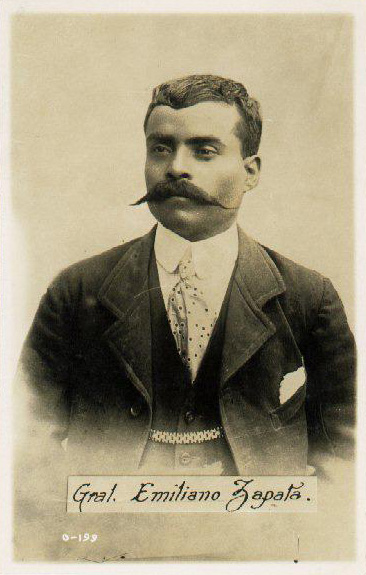

Then, and in subsequent Mexican political and social movements, "la Virgen" also became a symbol of freedom and a powerful emblem to rally political forces and support. A century after the Grito de Dolores -during the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917)- Emiliano Zapata and his agrarian rebels wore the Virgin's image on their hats. And in the late 20th century, another Mexican liberation movement, the EZLN (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional) led by the Subcomandante Marcos, has allegedly named their "mobile town" after la Virgen de la Guadalupe. In 1999, EZLN's sympathizers in Ocosingo, Chiapas, marched yelling slogans against the government of President Ernesto Zedillo and exalting "the insanity" of the interim governor of the state, Roberto Albores Guillen. According to the newspaper La Jornada:

The march was led by four women who had their faces covered with ski-masks, like all the others. The two youngest of them carried a Mexican flag; the others, who were mature, carried an image of the Virgen de Guadalupe and a crucified Christ on their breasts.

Besides, Virgen de la Guadalupe's image adorns churches and home altars, house fronts and interiors, bull rings and gambling establishments, taxis and buses, restaurants and even houses of ill repute. She is celebrated in popular song and verse. Her shrine at Tepeyac, in Mexico City, is visited each year by millions of pilgrims, ranging from the inhabitants of far-off Indian villages to the members of all walks of life, and international tourists and devotees. The Basílica de la Guadalupe is the most visited Catholic site in the world after the Vatican city. In 1987, the UNESCO included the old Basílica de la Guadalupe in its World's Heritage List.

Taking into consideration the powerful impact and cultural phenomenon of the Virgin, many historians and anthropologists since the mid-twentieth century, have focused on the symbolic nature of the "racial" identity of the Virgen de Guadalupe, emphasizing her image of a syncretic goddess and as cohesive national force in the Mexican imaginare. Many researchers have argued that her construct as mestiza reveals the appropriation and interpretation of Christian values and ideology by the indigenous peoples of Mexico, as well as the place of the value of mestizaje in the national identity and discourse.

Nevertheless, it is also important to recognize, that the Virgen de la Guadalupe's powerful image and adhesion in Mexican political, social and cultural fabric is the result of several centuries of elaboration, appropriations, inventions and changes. That's why I think that in the course of her history, The Virgen de la Guadalupe had many "avatars" or symbolisms. I shall reflect on the story/myth of the apparition and the historical development of the devotion for the Guadalupe.

Virgen de la Guadalupe: Between myth, story and history

First of all, the Virgen the la Guadalupe is between a "myth" and history. A myth, because for non-believers the whole notion of a spiritual apparition is on the realm of imagination, a non-sensical proposition and an impossibility. Is also a story that have been told and retold because involves an epic drama, an anecdote, that had a tangible result (the Virgin's impression on a cloak) and effect, (the building of the Basílica since 1531). Is also a historical phenomenon because the effects and interactions of the story/myth in Mexican culture.

Then lets discuss the contours of the myth/story of the Virgin the la Guadalupe...

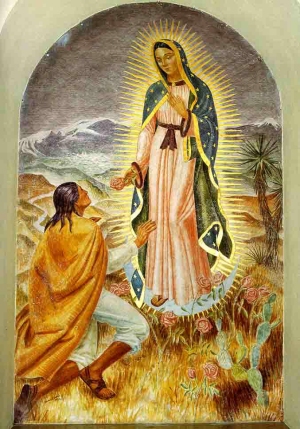

The Virgin and Juan Diego

According the story/myth, the encounter took place on the Hill of Tepeyac on December 12, I53I, just ten years after the Spanish Conquest of Tenochtitlan. There, the Virgin Mary appeared to Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin, a Christianized Mexica Tenochca native of commoner status, and addressed him in Nahuatl, his native tongue.

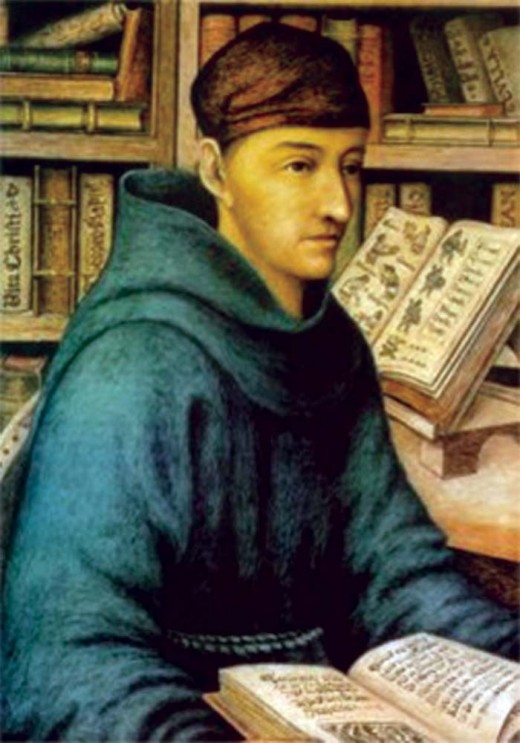

The Virgin commanded to seek out the bishop of Mexico and to inform him of her desire to have a church built in her honor on the Tepeyac Hill. After Juan Diego was twice unsuccessful in his efforts to carry out her order, the Virgin ordered Juan Diego to pick "Castille roses" in a spot where normally only desert plants could grow, then he will have to present the roses to the incredulous bishop, Fray Juan De Zumárraga, a franciscan.

Juan Diego gathered the roses into his cloak, and went to see bishop De Zúmarraga again. When Juan Diego unfolded his tilma before the bishop, the image of the Virgin was miraculously stamped upon it. The bishop acknowledged the miracle and ordered a shrine built where Mary had appeared to her humble servant.

The construction of the old basilica began in 1531 and was not finished until 1709. Above the central altar hangs Juan Diego's cloak with the miraculous image. It shows a young woman without child, her head lowered demurely in her shawl. She wears an open crown and flowing gown, and stands upon a half moon symbolizing the Immaculate Conception.

Virgen de la Guadalupe: Between Science and Faith

Mystery of the Virgen de la Guadalupe's eyes (in Spanish)

Juan Diego's tilma and the Scientists

The image of the Virgin de la Guadalupe was impressed on Juan Diego's cloak, made of maguey or Agave Americana. This is an endemic plant of Mexico from with its fiber is still used by Mexican natives to fabricate clothes. The tilma or tilmatli was a draped garment that allowed the Mexica male individuals the opportunity for displaying status and rank. Commoners could only wear the tilmatli to their knees; warriors could wear the tilmatli to their ankles only if they had wounded their legs in battle and needed to protect themselves from further harm. Noblemen and rulers alone could wear the tilmatli to their ankles.

For decades scientists have been puzzled by the fact that the alleged Juan Diego's tilma still exists today; the maguey fiber usually decomposes after two decades. The cloth where the image of the Virgin is printed, is already five centuries old, according to Carbon-14 analysis. Besides, "Juan Diego's tilma" was not protected from dust, humidity, etc. until decades ago.

The substance that pigments the cloak is still a "mystery" for the experts. Richard Kuhn , the Austrian Biochemist winner of a Nobel Prize in 1938, stated in the mid-1940s that the tilma"had not been painted with natural, animal, or mineral colorings". Since there were no synthetic colorings in 1531, the possibility of a native artist accomplishing a hoax seems out of the question.

Many other alleged studies of several experts are quoted in the contemporary accounts about "Juan Diego's tilma", many of those allegations are still under a heated debate between believers and non-believers. But my purpose here is not to debate the veracity or not about the "facts" or "myths" of the cloak, but to offer a historical approach to the cultural phenomenon, although limited.

You can check some of those arguments about the scientific findings about the cloak in the accompanying sources. Two of the videos are in Spanish. You can also visit this, this or this website (all in English) if you would like to know more about this specific issue.

Books about the Virgin of Guadalupe

The "Avatars" of the Virgen de la Guadalupe

AVATAR: an embodiment or personification, as of a principle, attitude, or view of life.

The emergence of the Virgen de la Guadalupe's cult

The shrine of the Guadalupe was not the first religious structure on the Tepeyac hill and she wasn't the first female supernatural being associated with it. In pre-Columbian times, Tepeyac had housed an Aztec temple to the earth and fertility goddess Tonantzin "Our Lady Mother" (in nahuatl). The Aztec deity, like the Guadalupe, was associated with the moon; and her temple, like the Basilica, was the center of large scale pilgrimages. The veneration later attached to the Guadalupe drew inspiration and it is much likely to be a continuation of the Tonantzin cult. Writing fifty years after the conquest of Mexico, Friar Bernardino de Sahagun, says in his Historia general de las cosas de la Nueva España, also known as the Florentine Codex:

Now that the Church of Our Lady of Guadalupe has been built there, they call her Tonantzin too.... The term refers ... to that ancient Tonantzin and this state of affairs should be remedied, because the proper name of the Mother of God is not Tonantzin, but Dios and Nantzin. It seems to be a satanic device to mask idolatry ... and they come from far away to visit that Tonantzin, as much as before; a devotion which is also suspect because there are many churches of Our Lady everywhere and they do not go to them; and they come from faraway lands to this Tonantzin as of old.

Sahagún also suspected that the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent, was being refashioned as the Apostle Thomas.

It is important to notice, that one of the very common practices of Spanish conquistadors of Mexico, was to destroy the temples and images of the Aztecs and, in its place, to built Catholic churches or Cathedrals. If you had the opportunity to visit this fascinating and diverse country, particularly Cholula in the state of Puebla, you will have a first hand impression of this phenomenon. In that city lies the world's biggest pyramid base, but you will not be able to see the pyramid. It was demolished by the Spaniards; in the top of the hill, you will see a Cathedral. From the hill where is situated the pyramid's base, you can take a look to the city and appreciate the hundreds (not a hyperbole!) of churches scattered around the city, most since the colonial period.

This modus operandi of Spaniards, was not just a concrete act to reject and obliterate the so called "pagan idols" of the mexicas, but also a strategy to spread the Christianism among the conquered people. This point of view may help to understand the transference of the cult of Tonantzin to the Virgin Mary by the natives. Also, to propose that the cult of the mestiza Virgin was created and fostered by the Church itself. After all, and like historian William B. Taylor have stated: "the Virgin Mary was introduced by Spanish masters as their own patroness, in hundreds of different images, and that she stood ambiguously for several meanings that were subject to change" (American Ethnologist (14:1) 1987).

What happened in Mexico with the transference of the cult of Tonantzin to the Virgin Mary, is parallel to some Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Brazilian religions with the devotion of saints, in which African deities from several religious traditions, were conveyed into Christian saints.

First "Avatar" of the Guadalupeña

In the first decades of the conquest, appeared the first "avatar" of "la Guadalupeña" (as called by Mexicans). Although the Virgin Mary, particularly in her depiction as a pregnant woman (as in the image of la Guadalupeña) is an embodiment of life and hope, in Spain was also closely associated with the land and fertility, as Tonantzin. For the Mexican natives, the Virgin became to incarnate even more. She represented a restoration or a renovation of life and culture. As anthropologist Erick Wolf stated in an article published in 1958:

To the Indian groups, the symbol is more than an embodiment of life and hope; it restores to them the hopes of salvation. We must not forget that the Spanish Conquest signified not only military defeat, but the defeat also of the old gods and the decline of the old ritual. The apparition of the Guadalupe to an Indian commoner thus represents on one level the return of Tonantzin. [...] On another level, the myth of the apparition served as a symbolic testimony that the Indian, as much as the Spaniard, was capable of being saved, capable of receiving Christianity. (The Journal of American Folklore, (71: 279) 1958)

Besides, Mexican natives not only faced military defeat and cultural. political and social subordination from Spanish conquistadors, but also the "Holly Inquisition". When the first Bishop of Mexico was appointed in 1535, one of his roles was to be also the Inquisitor. Juan de Zumárraga -Juan Diego's friend ; ) - was the first Bishop of Mexico. One of Zumarraga’s first acts as inquisitor, was the prosecution of an Aztec lord who took the name of Carlos upon baptism. He was likely a nephew of the Aztec philosopher, poet and warrior, Nezahualcoyotl. Zumárraga accused this lord of reverting back to worship of the old gods and had him burned at the stake on 30 November 1539.

History of the Virgin Mary and Mexico's History

Second "Avatar" of the Guadalupeña

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Franciscan and Augustinian used the cults of Mary Immaculate, as a symbol of charity and redemption, for the evangelization of Mexican natives. According to Taylor, during those centuries grew up an impressive number of local cults of Mary Immaculate in the hospital chapels founded by the Franciscans in Mexican native villages. Mary Immaculate was associated with the protection and destiny of particular villages.

During those centuries most of Guadalupe's early recorded miracles and shows of profound devotion are related to Mexico City and later, to other large cities. As Taylor argues in his 1987's article:

She was reported to have stemmed both the great flood of 1629 and the matlazahuatl epidemic of 1737-39, during which the archbishop formally proclaimed her patroness and protectress of the city "and its territory." Writing from Guadalajara in 1742, Licenciado Matías de la Mota Padilla still associated Guadalupe with Mexico City. He judged that "the whole world may envy Mexico City its good fortune in having the appearance of a sign as great as Holy Mary, who protects it."' Jose Joaqufn Fernandez de Lizardi, the famous Mexican pundit, writing in 1811, recounted that when a large meteor shower was sighted in 1789, most people of Mexico City believed it was fire from Heaven. In panicky disarray they fled to the shrine of Guadalupe, shouting "To the sanctuary, to Our Lady of Guadalupe."" When blanket statements about widespread devotion appear in the record, the chroniclers' specific examples are for Mexico City and ciudadanos mexicanos (people of Mexico City), or for San Luis Potosí, Valladolid, Puebla, Guadalajara, Zacatecas, and other large towns.

On the other hand, interpretation of the Virgin Mary as mother and intercessor, among Mexican natives presents a paradoxical message for colonial political life. As Taylor explains, most scholars have considered the Virgin's political significance as revolutionary and a symbol of a counterculture and liberation, but there is another consideration. As mediator, "the Virgin was a model of acceptance and legitimation of colonial authority".

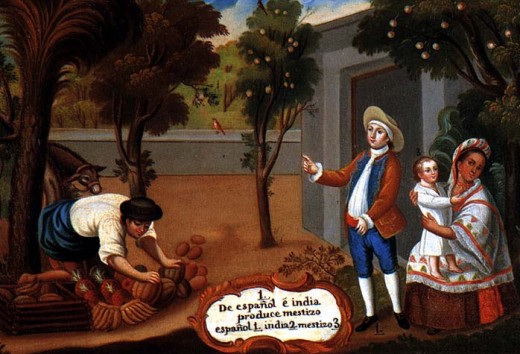

Third and Fourth "Avatar" of the Guadalupeña

During the second century of the development of a colonial society, the story of la Guadalupeña also held appeal to the large group of the disinherited, impoverished and illegitimate offspring of Spanish fathers and Indian mothers; who the Spanish called, mestizos. Although these groups acquired influence and wealth in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, they were barred from social recognition and power by the prevailing economic, social and political order. To them, as Wolf have pointed out, "the Guadalupe myth came to represent not merely the guarantee of their assured place in heaven, but the guarantee of their place in society here and now".

Along with the Native interpretations the Guadalupeña, as the return of "Our Lady Mother" (Tonatzin), during this period, she also incarnated the aspirations of the mestizos. As social group who was in the middle of two worlds and cultures, the mestizos, where not considered either as Natives, nor a Spaniards. And they didn't have the entitlements that either of those classes enjoyed in the colonial society. For them, the Guadalupeña became a liberator. This "avatar" dominated in the political discourse of this group or casta and served as a cohesive force for the struggle for independence in the early 19th century.

During the course of the fight of independence, the Virgin evolved into another "avatar": the protectress of Mexicans. Then the Virgen de la Guadalupe was taken as a spiritual ally of common people in revolt. She was also invoked for aid against hated new taxes, for an ideology of autonomy and community, and for the protection of the poor.

I guess now the call of Hidalgo in 1810 makes more sense for us:

My children: a new dispensation comes to us today. Will you receive it? Will you free yourselves? Will you recover the lands stolen three hundred years ago from your forefathers by the hated Spaniards? We must act at once… Will you defend your religion and your rights as true patriots? Long live our Lady of Guadalupe! Death to bad government! Death to the gachupines (Spaniards)!

Thus, the roots of the contemporary views and symbolism of the Virgin the la Guadalupe probably owes more to the political discourse of the independence era, than to the particular needs of the colonial church and peoples. Maybe that's why the Virgen de la Guadalupe is embedded in Mexico's national identity and political discourse. To be a devotee of the Guadalupeña is to affirm the Mexican identity and to be a real patriot, a true Mexican.

Carlos Fuentes, the renowned Mexican writer once said: "...one may no longer consider himself a Christian, but you cannot truly be considered a Mexican unless you believe in the Virgin of Guadalupe."