Community College Cuts: A "Liberal" Response

A Call for Real Investment into the Future

All indications are that education funding here in California is going to be slashed once again in this coming fiscal year. (It’s hard to say for sure, of course, since California has even more trouble passing a budget than Congress.) Several times, I have heard that an estimated 400,000 students will be turned away in the community college system this fall, and the story will likely be similar in the Cal State and UC university systems. This is part of a national story of state governments facing dire budgetary straits and being forced to cut all forms of public service.

I am aware of all of the arguments supporting these actions. California is $25 billion in the hole, and our state supposedly, due to its taxation and regulatory policies, is already an unfriendly climate for business. If Governor Brown’s plan of asking voters to extend about $12 billion worth of tax increases was ultimately successful, even more businesses would be chased away. And even with these tax increases, deep cuts will be necessary.

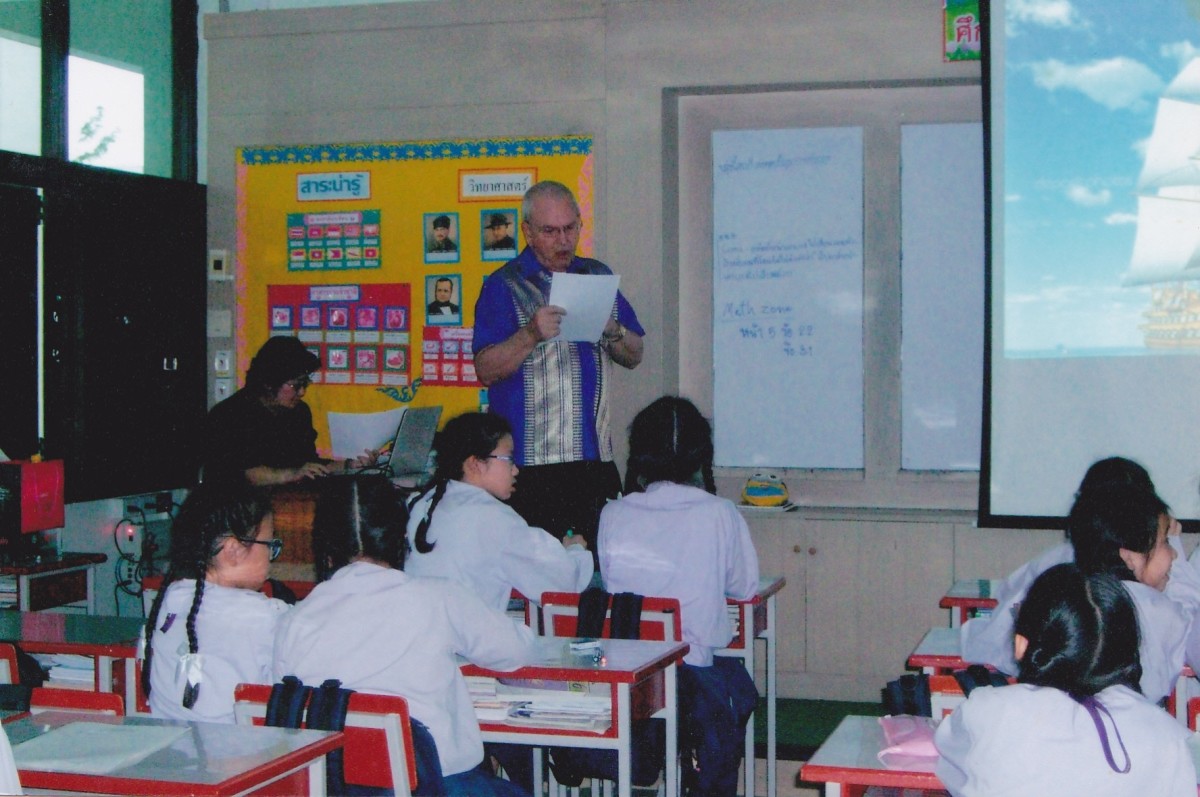

Since I am not running a corporation or small business, I cannot say for sure if this state is as unfriendly to businesses as many often claim. Given how often I hear this claim, I imagine that there must be some truth to it. I can from personal experience, however, describe the impact of slashes to education funding. I have been forced to turn away dozens of students hoping to squeeze in to already full courses. I have struggled to piece together enough classes from three (or four) schools in order to make a living. Full-time community college teaching positions are scarcer than ever. And in a country where a college degree is increasingly vital for success, I shutter to think of the long-term effects of limited access to an affordable education.

So before I go off on what some may view as a liberal semi-rant, I will admit that community colleges may need to experiment with some new, more creative austerity measures. There must be something more that can be done than cutting classes and turning away students. Cuts to the administrative bureaucracy should be looked at first, although I recognize that this will not solve the problem completely. We may also, unfortunately, need to rethink the concept of a completely “open” school system. Maybe admission standards need to be raised somewhat. Too many students who are completely unprepared for a college level class are being enrolled, and they often end up either failing or dropping before the class has ended. Essentially, they are taking up space that could better be utilized by others. Then, after failing or dropping, they enroll for the same courses again, once again closing off opportunities for more conscientious, qualified students. Limits may need to be set on the number of times a students can repeat a course. At the least, they should be required to pay a higher price for classes that they have enrolled in before and failed to pass. Because classes in California are still so relatively cheap, and large numbers of students are on financial aid, the cost of failure or quitting is relatively low. Too many students feel that they can just start over again with little cost to them. It may no longer be possible for the government to provide low cost classes for everyone who wants to enroll, so the only options are to have students pay more and to be held more accountable for their performance. Still, given the scope of the budget cuts, reductions in classes offered and students served are inevitable.

The experiment of public education began in the early 19th century. As time passed, government subsidized education was extended, with free schooling available through high school. Eventually, as the need for college-educated citizens grew, government sponsored community colleges and universities increasingly appeared. Now, after decades of seeing educational opportunities extended, our nation seems to be going in the opposite direction. The need for an educated workforce, however, only continues to increase. These trends that are going in opposite directions have some dire economic, political, national security, and cultural implications.

Many Americans have been in an anti-government, anti-tax mode for decades. Given the growth of government spending and its increasing roles and responsibilities over time, this is understandable. Since the days of Reagan, many have clung to the notion that cuts in taxes and spending are the key to economic prosperity. I see increasing evidence, however, that this definition of prosperity is rather limited, and it may not be sustainable. Certain industries have undoubtedly flourished over the past thirty years, aided by an ideology and by lobbyists trying to make government more business friendly. I suspect, however, that much of this prosperity had more to do with technological innovation, global economic growth, and easy credit than with pro-business political policies. And after decades of supposed prosperity, what do we have to show for it? We are paying historically low federal taxes, and the economy is still sputtering. The federal government is nearing a debt to GDP ratio not reached since the days of World War II. Basic services provided by states are being slashed throughout the country. The United States spends more of its GDP on medical services than any other nation, and yet we are ranked very low in national health standards. The financial sector that caused much of this mess is more consolidated than ever, with the biggest banks being even bigger than when they were “too big to fail.” And while nations such as China, India, and Brazil pour resources into education and infrastructure, all that the United States government can do is talk about cuts.

Sure, The United States is still the biggest economy on earth. The wealth, however, has disproportionately gone to the wealthiest Americans over the past three decades. And the federal government, rather than using its resources to invest in the future, spends most of its money on a bloated military and on retirees. What about the young people who are supposed to pay for our increasingly elderly population? What about those who find themselves obsolete due to technological advances in our rapidly changing economy? And if we care enough about national security to be currently involved in three military conflicts, why are we not worried about the future, potential impact of large numbers of frustrated Americans unable to find meaningful work that pays decently? People say we cannot afford education. I don’t see how we can afford not to educate. Investment now will save a lot of money and hardship in the long run.

Of course, you might argue that my main motive in pushing for education funding is the maintenance of my job. I cannot completely deny this. We are all biased by self-interest, and everyone knows that educators are a bunch of liberal hippies. But believe it or not, I try in my ramblings to be unbiased. I’m finding it difficult, however, to be tolerant of the current brand of so-called conservatism in this country. This undying, almost religious faith that tax cuts, deregulation, and reductions in spending will lead to boundless prosperity and balanced budgets has little basis in reality. Part of the problem is the inability or unwillingness of “conservatives” to propose reductions in spending that come close to offsetting the tax cuts. But an even deeper issue, in my mind, is both an ignorance of history and a narrow vision of the world. Is there a direct correlation between tax cuts and economic growth? Did Ronald Reagan, the founding father of the modern Republican Party, refuse to ever raise taxes in any circumstance? Has the economy generally performed better under “pro-business” Republicans than “tax and spend” Democrats? Many might find the answers to these questions surprising. If nothing else, an objective look at these historical questions would lead many in this country to rethink their simplistic assumptions.

Government exists to serve the public interest. People do not agree, however, on what the term ‘public interest” means. In my mind, it is in the general public interest for people to have the opportunity to be safe and successful. Education plays a major role in both of those areas. Uneducated people, after all, are more likely to be unproductive and dangerous. And the biggest threat to me is not an attack from a foreign army or terrorist. It is either an attack from another American or an inability to find a job. Until our society takes a more proactive view – supporting investment into infrastructure and education – rather than a primarily reactive view – investing into weapons, cops, and jails – we will continue to have problems. Higher taxes may be necessary to make this happen, and past experience indicates that this will not necessarily stifle economic growth. And in the end, a society willing to spend hundreds of billions on weapons and military personnel – and even more on its increasingly elderly population - should be willing to spend at least a significant fraction of that on the future prosperity of its young people.