Feminist Literary Theory

Introduction

The term feminism has become rather impossible to define in just one statement. I would, however, sum it up by saying that feminism is a social and political movement that incorporates different sets of ideas and branches dealing with a woman’s place in the social, cultural and political dimensions. In this respect, before one delves into the different thoughts and ideas that emerge from the Feminist Literary Theory, the historical feminist structures should be taken into consideration.

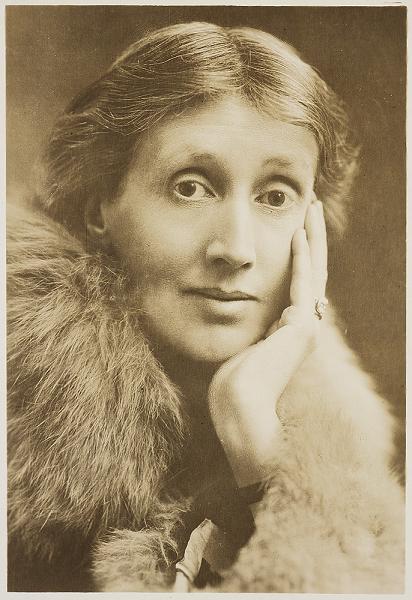

The first feminist activity took place during the nineteenth and early twentieth century, when Mary Wollstonecraft’s ideas on the equality of the sexes triggered off the campaign for women’s suffrage and education. Although Virginia Woolf wrote her two main feminist works Killing the Angel in the House and A Room of One’s Own in the early twentieth century, her work became popular and widely read and referred to during the second wave of feminism. In fact, Mary Eagleton argues that it was Simone de Beauvoir and her text The Second Sex which filled the gap between the death of Virginia Woolf up to the 1960s, when the second wave of the feminist movement began.[1]

From the 1960s onwards, the literary world exploded with diverse feminist texts written by different women writers expressing their individual ideas. These include Kate Millet’s Sexual Politics, Gilbert and Gubar’s The Madwoman in the Attic, Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch and Mary Ellman’s Thinking About Women, just to name a few. These feminist literary critics were opposed by other Feminist critics who spoke in favour of black women and lesbians, whose issues had been overlooked by the white heterosexual feminists.

Recently, third-wave feminists have been trying to continue promoting reproductive rights and eliminating sexual harassment and domestic violence. Although feminists hailing from different branches of thought, such as the liberal, radical and socialist feminists, tend to disagree amongst themselves, there are certain criteria which they all agree on. These include issues such as ending sexual violence and inequality, while promoting women’s right to terminate their pregnancies.[2]

A different approach to feminism, which veers from the sociological approach of women’s standpoint in society, is taken up by the Feminist Literary Theorists, who aim at analyzing the position of women and representation of gender in literature by male authors. In the following paragraphs, I will be touching on the different theories that relate to gender and literature which have been discussed by some of the most influential feminists of the twentieth century.

[1] Mary Eagleton, ‘Who’s Who and Where’s Where: Constructing Feminist Literary Studies’ in Feminist Review, no. 53 (Palgrave Macmillan Journals, 1996) p. 3 in JSTOR <http://www.jstor.org.ejournals.um.edu.mt> [accessed 15May 2010]

[2] John J. Macionis and Ken Plummer, ‘The Gender Order and Sexualities,’ in Sociology: A Global Introduction, 3rd edn (Harlow: Pearson Education Limited, 2005), p.323.

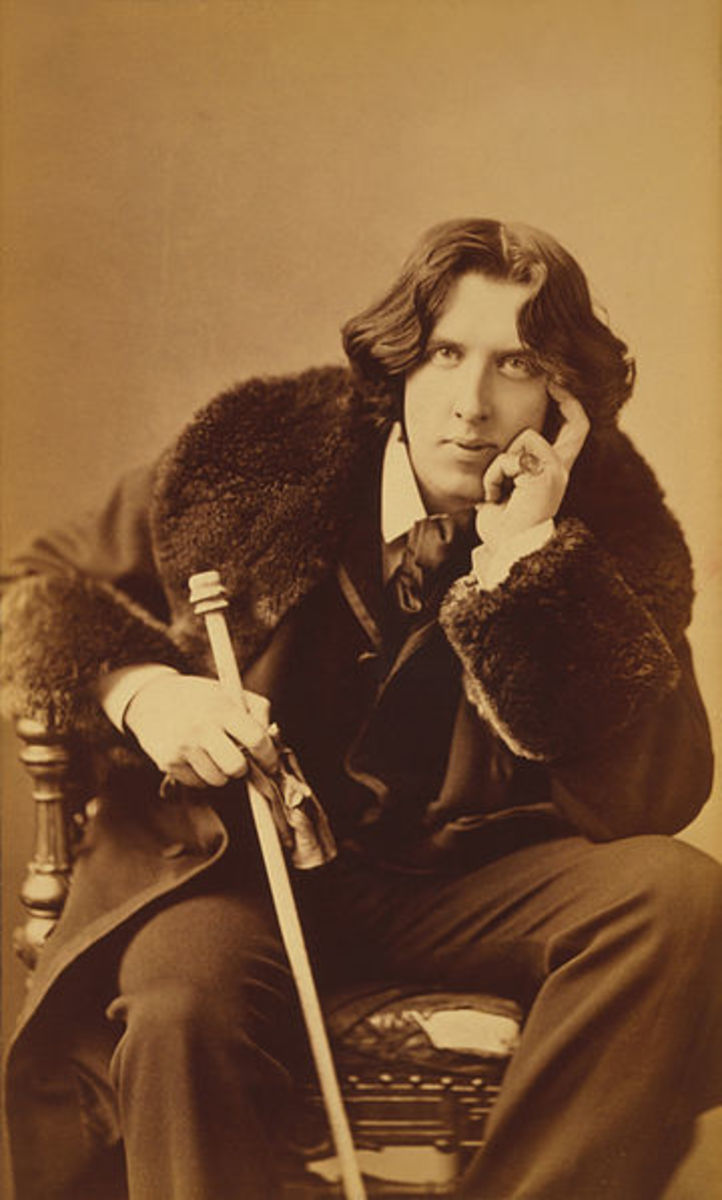

Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own is considered to be the first modern work of feminist literary criticism. [1] Woolf’s feminist agenda encourages the readers to become critical analysts of power and gender as represented by male authors in their texts. Moreover, she also questions the absence of women writers in the literary canon. She scrutinises the fact that ‘a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction,’ and most women of her time were deprived of these material necessities.

In Killing the Angel in the House, Woolf points out the domestic repression that Victorian female writers like Jane Austen, Miss Burney, Charlotte Bronte and George Eliot had to go through when they tried to write. Woolf’s idea of the ‘angel in the house’ stands for the submissive woman who ‘never had a mind or a wish of her own.’[2] Therefore, in order for a woman to possess an independent mind and start writing freely, she needs to silence the voice that tells her to be submissive to the patriarchal needs and demands of society. This idea of a woman possessing an independent mind is also conveyed through Woolf’s novels and essays, where the feelings and thoughts of characters are communicated through the female protagonists and not through the authorial voice.

Elaine Showalter perceives Woolf as ‘the apotheosis of a new literary sensibility’[3] which is androgyny. In this context, being androgynous means developing a balance of maleness and femaleness in one’s character. Woolf tried to attain this androgynous characteristic by writing journalism that is associated with maleness, and fiction which is considered to be feminine. However, Showalter believes that Woolf did not succeed in being androgynous since she was as restrained and frustrated as the women in A Room of One’s Own. More than that, Showalter believes that being androgynous is just an unattainable vision.

[1] Jane Goldman, ‘The Feminist Criticism of Virginia Woolf’ in A History of Feminist Literary Criticism (Cambridge University Press, 2007) p. 66 in Google Books <http://books.google.com.mt> [accessed 15 May 2010]

[2] Virginia Woolf, ‘Professions for Women’ in Killing the Angel in the House (London: Penguin Books Ltd, 1995) p.3.

[3]Mary Eagleton, ‘Elaine Showalter and Toril Moi’ in Feminist Literary Criticism (Longman Pub Group, 1991) p. 25.

Kate Millet

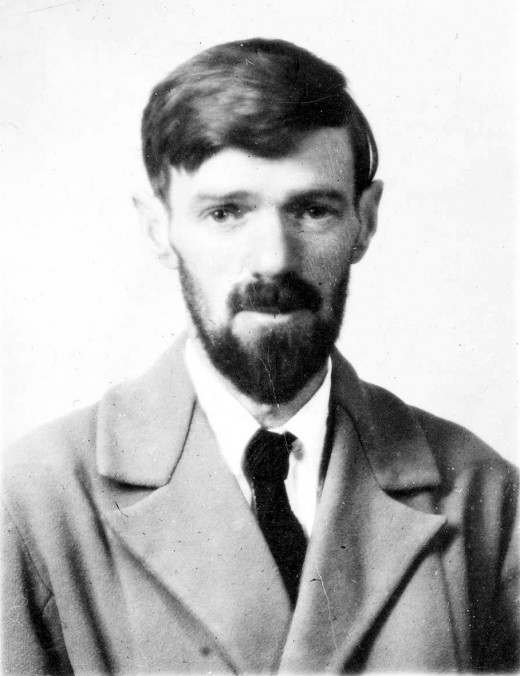

A Feminist Literary Critic who takes a different feminist stance from Woolf is Kate Millett, whose famous book Sexual Politics deals with a history of patriarchy and a critical approach to novels by D.H Lawrence and Henry Miller. Millett’s main focus is on the Lawrentian portrayal of women in his novels. Millet says that the sexual intercourse scenes in Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead are a perfect example of male domination and female passiveness. This representation of the sexes in literature reflects the way things are in reality.

Millet shows how ‘Lawrence conveys his message of male supremacy through his female characters.’[1] She also argues that the Lawrentian heroines are non-intellectual and passive and their only fulfillment in life is submitting to their male counterparts. Although Ursula Brangwen in The Rainbow acts against her parents’ orders and pursues further education in order to become a teacher, in Women in Love she quits her job once she marries Birkin. Ursula was once a competitive and an independent woman but she submits to the patriarchal world once she decides to get married. On the other hand, Millet believes that the Lawrentian heroes are bullies, dominant and represent sexuality and phallic divinity.[2] However, as I will illustrate in my conclusion, Millet’s argument is quite lacking in credibility.

[1] Janet H. Harris, ‘D.H Lawrence and Kate Millet’ in The Massachusetts Review, vol. 15 no. 3 (The Massachusetts Review Inc, 1974) p. 522 in JSTOR <http://www.jstor.org.ejournals.um.edu.mt> [accessed 15May 2010]

[2] Mary Eagleton, ‘Kate Millet and Cora Kaplan’ in Feminist Literary Criticism (Longman Pub Group, 1991) p. 139.

Toril Moi and Elaine Showalter

In her book Sexual/Textual Politics: Feminist Literary Theory, Moi maintains that the interest in women writers started in the Seventies, when Showalter had said that ‘women writers should not be studied as a distinct group on the assumption that they write alike’[1] but women’s social, political and economic positions and the stereotypes associated with women writers need to be considered.

Moi mentions three main Anglo-American feminist texts that attracted and inspired a large number of female scholars and students. These are Elaine Moers’s Literary Women, Showalter’s A Literature of Their Own, and Gilbert and Gubar’s The Madwoman in the Attic. According to these critics, it is society that determines a woman’s ‘literary perceptions of the world’[2] and not her biological makeup.

In the Seventies and Eighties, the Feminist Literary Theory was mainly dealing with women and their contribution to art, creativity and writing. This period witnessed the advent of many female writers who were finally able to express their feelings and passions in writing for women readers. Women could finally depict female characters from their own perspectives and experiences. Not every female writer, however, was pleased with the importance that many feminists were giving to gender and literature. As Moi reveals, some female writers like Nathalie Sarraute, were rather annoyed by the fact that there work was defined as being written by a woman.

For Elaine Showalter, ‘the female literary tradition comes from the still-evolving relationships between women writers and their society.’[3] Showalter divides the history of the female literary tradition, which according to her is a sub-culture, into three phases. The Feminine phase marks the start of women writers submitting their books for publishing under male pseudonyms. The second period is the Feminist, which runs from 1880 until 1920 and is characterized by protests for voting rights. The Female phase followed from the 1920s onwards, which Showalter describes as being ‘a phase of self-discovery.’[4] Showalter divides feminist criticism into two; feminist as readers and feminist as writers. The feminist readers analyse and interpret the stereotypes of women as depicted in literature. Showalter argues that if these feminist readers spend too much time going through the male critical theory to correct it and attack it, they will not be helping much with feminist issues. Showalter defines the male critical theory as ‘a concept of creativity, literary history, or literary interpretation based entirely on male experience and put forward as universal.’[5] The second mode of feminist criticism, the women writers, studies the themes, structures, genres, creativity and styles of writing by women. Showalter uses the term ‘gynocritics’ for this type of critical discourse, and says that it these gynocritics which provide the opportunity to overcome the theoretical problems that many women have to face in a male-dominated society.

[1] Toril Moi, ‘ Women Writing and Writing About Women,’ in Sexual/Textual Politics: Feminist Literary Theory (USA: Routledge, 2002) p. 49 in Google Books <http://books.google.com.mt> [accessed 15 May 2010]

[2] Toril Moi, ‘ Women Writing and Writing About Women,’ in Sexual/Textual Politics (see above) p. 52 in Google Books <http://books.google.com.mt> [accessed 15 May 2010]

[3] Toril Moi, ‘ Women Writing and Writing About Women,’ in Sexual/Textual Politics (see above) p. 51-52 in Google Books <http://books.google.com.mt> [accessed 15 May 2010]

[4] Toril Moi, ‘ Women Writing and Writing About Women,’ in Sexual/Textual Politics (see above) p. 55 in Google Books <http://books.google.com.mt> [accessed 15 May 2010]

[5] Elaine Showalter, ‘Feminist Criticism in the Wilderness,’ in Critical Inquiry, vol. 8 no. 2 (The University of Chicago Press, 1981) p. 183 in JSTOR <http://www.jstor.org.ejournals.um.edu.mt> [accessed 15May 2010]

Conclusion

Despite the different theoretical concerns that Feminist Literary theorists bring up, they all unite to advocate women’s interests in the literary world. The only Feminist critic whose argument I find rather unconvincing is Kate Millet. Millet believes that men write about women to define themselves against the feminine characteristics of their protagonists. She does, however, leave out the possibility that even a female writer can write about a male character and shape him as she pleases, even though the female writer does not know so much about men and their psyche. The woman writer could have degraded the male characters, but such portrayal of men in literature would have been unacceptable and unconventional at the time when women writers like Austen, Bronte and George Eliot were writing. That might be one of the reasons why these women writers resorted to continue highlighting the submissiveness of women and their mistaken judgement of men. For example, in Eliot’s Middlemarch, the intelligent Dorothea Brooke’s rash decision to marry the old Casaubon leads her into a loveless marriage. Dorothea realises that she has made a big mistake when she starts being ignored and resented by her husband who locks himself in his study to finish writing his research.

When it comes to her negative criticism of D.H Lawrence, I believe that Millet is only pointing out the things that fit into her theory and neglecting the other things that challenge her perceptions about Lawrence’s novels. Millet fails to notice that Lawrentian intellectual heroes like Anton Skrebensky are devoid of a spiritual sense of life, and that was the reason why Ursula refused to marry him. Another thing which Millet leaves out is the fact that after marrying Ursula, Birkin also gives up his job of a school inspector.

The following quote from Harris’s D.H Lawrence and Kate Millet summarises another point which Millet fails to mention:

‘For every instance Millet finds of a Lawrentian heroine submitting, one can uncover ten of that same heroine struggling, doubting, fighting, winning – and with the blessing of the novelist; for every example of a hero domineering his partner, one can point to countless of him honoring her opposite, contrary self.’[1]

In relation to what Virginia Woolf had to say about women writers, I believe that nowadays it has become easier for a woman to ‘kill the angel in the house’ and indulge in writing. Nonetheless, the works of female writers are still slowly being filtered through the Western canon. Showalter recounts that when she looked at the syllabi of the English Department of the women’s college which she used to attend to, the students were covering works by over three hundred male writers and only seventeen women writers.[2]

She goes on to say that as a result of this imbalance in the syllabi, women students will get the impression that the men’s viewpoint in literature is the norm.This is reminiscent of what Simone de Beauvoir says in The Second Sex, that a sexist society views man as the universal being, the One, and the woman as the Other.[3] Showalter states that the female students will therefore have to try to experience things from a masculine perspective, which is expected to be the norm in society.

All things considered, I agree with Nancy K. Miller when she argues that women should continue fighting for their place in the academic world and that the work of women writers should be introduced in the literary canon.

[1] Janet H. Harris, ‘D.H Lawrence and Kate Millet’ in The Massachusetts Review, vol. 15 no. 3 (The Massachusetts Review Inc, 1974) p. 524 in JSTOR <http://www.jstor.org.ejournals.um.edu.mt> [accessed 15May 2010]

[2] Elaine Showalter, ‘Women and the Literary Curriculum’, in College English, vol. 32 no. 8 (National Council of Teachers of English, 1971) p856.

[3] Toril Moi, ‘I Am Not a Woman Writer’ in Eurozine <http://www.eurozine.com/articles/2009-06-12-moi-en.html>[accessed 15May 2010]