- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era

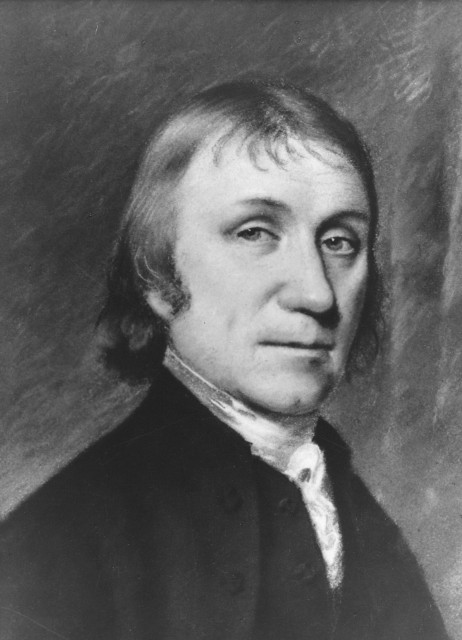

Joseph Priestley: Unitarian, Inventor, and Riot- Inducer.

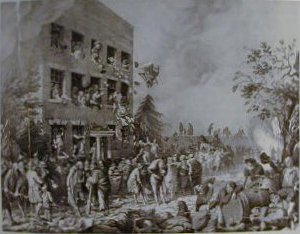

On the night of July 14th, 1791, Dr. Joseph Priestley must have feared for his life. An unruly mob of hundreds had, only moments ago, set a torch to the New Unitarian Meeting House, the church where Priestley had given sermons for years. Now, it was communicated, they were growing in numbers and were making haste for Priestley’s residence, with the likely motivation of destroying Priestley’s home and all within it, and perhaps, inflicting damage upon Priestley himself.1 It is unlikely that Dr. Priestley was completely surprised at the events that were now unfolding. He may have underestimated the gravity of the situation, may have found it difficult to comprehend the reality of such a dangerous situation, but the storm had been brewing for years now, and at the very least, Priestley must have realized the power of words, and how easily certain words can erupt into violence.

Birmingham in the late 18th century was known for its tolerance of religious dissension. After all, the “Unitarians were more strongly entrenched in Birmingham than in any other city.”2 Answering a request to become minister for Birmingham’s New Meeting, a Unitarian church, Priestley and his family moved there in 1780, and for the next decade lived in relative peacefulness.

There was, however, no end in sight to the disagreements and controversies, not to mention laws, arising out of varying religious interpretations. Simply put, religious observers of 18th century England generally fell into two camps: Those belonging to the Church of England, or Anglicanism, and those who did not. While dissension was, for the most part, tolerated, laws limiting the freedoms of religious dissenters had been enacted and were still observed. Most notably of these laws was the Corporation Act of 1661, which barred religious dissenters from holding public office, both military or civil.

The Test Acts, passed twelve and seventeen years later years later, went even further in requiring all current office holders to take oaths swearing allegiance to the Church of England, as well as signing a declaration against transubstantiation.3 “In the late 1780’s however, there arose an issue which was of vital concern to all dissenters. This was the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts, and it had to be considered by a parliament in which dissenters were a tiny minority.” 4

Birmingham, while having a large amount of religious dissenters, particularly Unitarians, was nevertheless predominantly Anglican. Religious affiliation in Birmingham seemed to follow class lines: the wealthier, more “refined” men of Birmingham choosing dissension, while the artisan, laborer class allying themselves with the traditional Church of England.5 Priestley was part of Birmingham’s upper class. Educated, moderately wealthy and outspoken, Dr. Priestley was probably quite distanced from the working class of his town. His religious views, and candid openness regarding them, were largely unappreciated by the majority of Birmingham’s residents.

Besides preaching Unitarian doctrine from the New Meeting house every Sunday, Priestley had published numerous works on the subject and had engaged in a fair share of “pamphlet wars” with Anglicans.6 Priestley’s claim, elucidated in his exhaustive work “A History of the Corruptions of Christianity,” that modern-day Christianity had been perverted throughout the years and that the Bible had been misinterpreted, was controversial, to be sure, but didn’t exactly warrant the threat of physical violence. The fundamental difference between Priestley’s Unitarianism and the mainstream Christianity of the day was a denial of both the Trinity and of Christ’s divinity, beliefs that were sure to generate controversy, if not anger, among Anglicans in Birmingham and beyond.7 But it was not so much Dr. Priestley’s stance on religion, rather his outspoken and blameless demeanor that so incensed his opponents. Kathy Hutton, daughter of Priestley’s friend William Hutton and fellow Unitarian, writing after the Birmingham riots, described Priestley’s attitude:

Having fully assured himself of the truth in religion, he conceived it his duty to go abroad into the world and endeavour to persuade all mortals to embrace it, an idea which has done more mischief than any which ever entered the erring mind of man…He was himself so unconscious of having done wrong, nay, he was so certain of having done only right, that his friends took him almost by force and saved him from the vengeance of a mob who would have torn him to pieces.8

A large part of the religious controversy of the day was generated by attempts to repeal the Test and Corporation Acts. The first concerted effort for repeal in Priestley’s time was in 1772, when Priestley’s friend, Theophilus Lindsey, along with others, petitioned Parliament “to abolish subscription to the Thirty-Nine articles, required of those in Anglican orders upon nomination or promotion.” 9 After this failure to repeal, efforts were by no means diminished. At the forefront of the repeal movement was Dr. Priestley, who had, in 1787, published A Letter to the Right Honorable William Pitt, First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer; on the subject of Toleration and Church Establishments; occasioned by his speech against the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts, on Wednesday, the 21st of March 1787.10 HHH In addition to publishing numerous pamphlets on the subject, had preached a sermon on November 5th, 1789 titled, The conduct to be observed by Dissenters, in order to procure the repeal of the Corporation and Test Acts.11 The reactions to this sermon were heated and aggressive, and it sparked a back and forth debate between dissenters and church loyalists, a debate that grew increasingly personal and impassioned. P.B. Rose, in his article, The Priestley Riots of 1791, writes:

The publication of this sermon was the prelude to a bitter controversy in which Priestley and the dissenters were attacked from the pulpits of St. Philip's and St Martin's. The tone of George Croft, lecturer at St. Martin's, was noted for its particular virulence. In one sermon, printed in I790, he charged the dissenters with Republican principles, regretted that their right to vote for Members and to sit in Parliament could not be withdrawn, and - an ominous note warned his hearers that "while their meeting-houses are open they are weakening and almost demolishing the whole fabric of Christianity.12

It may be said that the efforts at repeal by Dissenters marked the true beginning of instability in Birmingham that would eventually culminate in the riots of 1791. According to Katherine Hutton, “Party spirit had been declining for an age, and seemed totally annihilated in Birmingham, where trade had mingled all its votaries in one mass. The first circumstance which revived the distinction between the Churchman and the Presbyterian was the application of the Dissenters to Parliament for the repeal of the Test Act.” 13 If this was the spark, then the ensuing pamphlet wars were the fuel that fed the fire.

These disputes, which often focused less on the Test and Corporation Acts and more on the question of Christ’s divinity and the legitimacy of the Trinity, became more and more heated, and increasingly personal. Spencer Madan, rector of St. Philips Church in Birmingham, was one of the most active of Priestley’s opponents in this regard. In his “Letters to Dr. Priestley occasioned by his Late Publications,” Madan alludes to Priestley’s love of controversy when he states, “…I am so little jealous of the honors, or envious of the happiness which you seem to derive from a perpetual immersion and floundering in the troubled waters of controversy.” 14 Madan’s brother, Martin, a chaplain in London, also jumped into the foray. In his Letters to Joseph Priestley, occasioned by his late controversial writings, Madan argues against Unitarianism, particularly in support of the Trinity. Madan defends his position in not so cordial words, saying, “I will not enter into idle cavils, or, in other words, into the perverse disputings of men of corrupt minds, who are destitute of the truth…” 15 The scripture used in describing Dr. Priestley as “perverse,” “destitute of truth,” and corrupt” is evidence of the debate’s intensity, and yet the riots would not occur for another four years. Priestley’s replies to Madan were no less spiteful. In Familiar Letters III, On Test and Corporation Acts, Priestley, regarding the Test and Corporation Acts, “maintained that they were only necessary for the financial maintenance of corrupt churchmen.” 16

Priestley’s enemies were hardly limited to the adherents of Anglicanism. Fellow Dissenters such as John Wesley were opposed to his teachings as well. Wesley went so far as to brand Priestley “one of the most dangerous enemies to Christianity,”17 an accusation that echoed that of George Croft, lecturer at St. Martin’s church in Birmingham, who cautioned his audience that “while their meeting houses are open (Unitarians) they are weakening and almost demolishing the entire fabric of Christianity.” 18 In light of such alarming accusations against Priestley and his Unitarian beliefs, it is hardly surprising that the emotions of Birmingham’s residents could be raised to such a violent pitch, and culminate in four days of destruction; destruction that was almost exclusively reserved for religious dissenters. 19

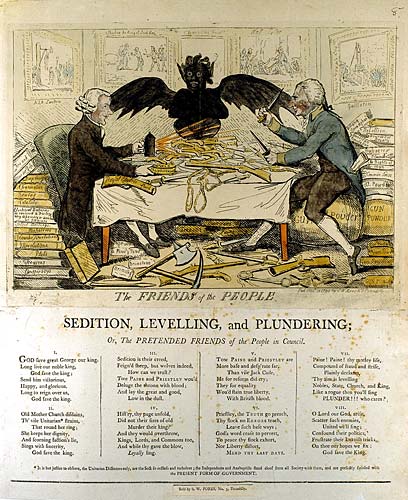

Aside from religious controversies, Priestley engaged in those of a political nature as well. However, the two subjects were not often independent of one another in 18th century England. Priestley himself maintained that he was “not, nor ever was a member of any political society whatsoever, nor did I ever sign any paper originating with any of them.” 20 While it may be true that Priestley never signed any document indicating political affiliation, he was anything but an innocent bystander when it came to the political sphere. The Warwickshire Constitutional Society, for instance, was a group formed in June of 1791 whose first principle was “That the sole object of all civil government is the temporal interest of the people who compose any civil society.”21 Priestley was involved in the formation of this society to the extent that he had persuaded two fellow member of the Lunar Society, James Watt and Matthew Boulton to join a mere two weeks before the riots were to occur.22 While this was hardly the revolutionary society many must have assumed it to be, any political meddling by Priestley, given his unorthodox views on religion, would have been viewed with suspicion. The activity of the French Revolution raised suspicions and heightened political tensions in England, and those parties sympathetic to the Revolution were watched with increased vigilance.

Priestley’s work, Reflections on the Present State of Free Inquiry in this Country, didn’t help his reputation in the slightest. In it, he used the analogy of gunpowder in relation to his theological arguments, saying, “We are, as it were, laying gunpowder, grain by grain, under the old building of error and superstition, which a single spark may hereafter inflame, so as to produce an instantaneous explosion: in consequence of which, that edifice, the erection of which has been the work of ages, may be overturned in a moment, and so effectually that the same foundation can never be built upon again."23 This analogy, while innocent enough, conjured up images of the Gunpowder Conspiracy of November 5th, 1605, in which conspirators attempted to assassinate the king by blowing up the Houses of Parliament. Not only were Priestley’s words often taken out of context, Priestley continued to use the analogy, despite its implications. This had earned Dr. Priestley the nickname, “Gunpowder Joe,” and furthered suspicions that Priestley was a dangerous revolutionary.24

A dispute within Birmingham over the local library furthered incensed residents against Priestley, although, once again, Priestley seems to have had noble intentions throughout the affair. Taking over its management in 1780, Priestley initially intended for there to be no inclusion of books of a controversial nature, his own included, and had hoped, naively perhaps, that the library would “…promote a spirit of liberality and friendship among all classes of men without distinction.” Unfortunately for Priestley, the library’s committee, once nearly all dissenters, consisted of a group of churchmen in 1786. Surprisingly, this group pushed for the inclusion of Priestley’s controversial work, “A History of the Corruptions of Christianity” into the library. The churchmen though, had ulterior motives, Historian John Money writes, “This manoeuvre produced predictable results. The acquisition of Priestley’s work was attributed not to the cabal on the committee but to the Doctor himself and his friends, and it was followed by a series of ostentatious Anglican protests and resignations.” After this event, Priestley reversed his original stance, and fought for the inclusion of any and all controversial works in the Birmingham library, even, or especially those that contradicted his own writings. 25

This event, in addition to numerous others, furthered the divide between Doctor Priestley and Anglican residents of Birmingham. For the lower-class laborer of Birmingham, loyal to the Monarchy and the Church of England, unconcerned with lofty subjects such as philosophy and natural science, Priestley and his world must have seemed almost foreign. The fact that Priestley spent his time in intellectual pursuits within his Lunar Society, that he kept company with dissenters, aristocrats and Revolution sympathizers, and that he was quite well-off by the standards of the day must have all contributed to the great dislike many in Birmingham felt for the Doctor. It is probable that in addition to religious disparities, the mob that rioted from July 14th to the 17th was motivated by social bias as well. George Rude’ corroborates this idea when he writes, “The “hard and black hands” seem, in fact, to have been all the more willing to get to grips with the dissenters and philosophical radicals-the declared enemies of Church and King-because they were also the leading figures among the city’s wealthy middle class. Nor need this surprise us: we saw a similar social bias in the attacks on Catholic houses in London eleven years before.” 26

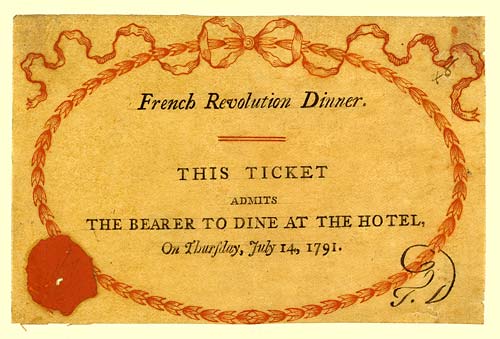

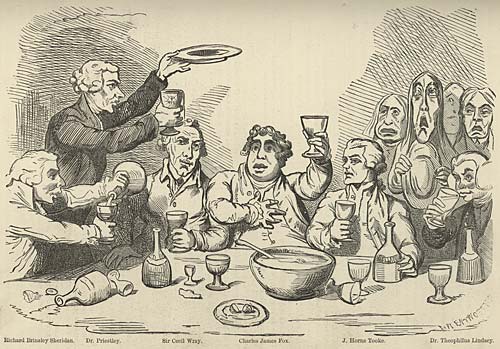

While Priestley gained most of his unpopularity through his theological disputes, it was in fact his political associations that were to set off the Birmingham riots. A celebratory dinner, to commemorate the falling of the Bastille two years ago, was planned by sympathizers of the French Revolution for July 14th, 1791. The local paper first advertised the event on July 11th, saying, “Any Friend to Freedom, disposed to join the intended temperate festivity, is desired to leave his name at the bar of the hotel, where tickets may be had at 5 shillings each, including a bottle of wine; but no person will be admitted without one.” 27 Interestingly, the author of An authentic account of the riots in Birmingham, on the 14th, 15th, 16th, and 17th days of July, 1791, notes that “On the second appearance of this advertisement, in the Birmingham Gazette, the following was likewise inserted: “On Friday next will be published… an authentic list of all those who dine at the Hotel, Temple Row, Birmingham, Thursday the 14th instant, in commemoration of the French Revolution.” This strange addition, appears to have been a sort of veiled threat for those planning on attending. The aforementioned author believed so, as he goes on to say, “This last advertisement was certainly intended to intimidate the meeting at the Hotel, and alarm the people.”

Also to be noted was an anonymous revolutionary hand-bill that had been circulated throughout Birmingham prior to the Dinner. In it, the author induced his (or her) readers to “…prove to the political sycophants of the day that you reverence the olive branch; that you will sacrifice to public tranquility, till the majority shall exclaim, The Peace of Slavery is worse than the War of Freedom. Of that moment let tyrants beware.” The timing of this hand-bill, as well as its inflammatory nature, did more damage to Revolution sympathizers than was probably intended. Many suspected it to have circulated for the sole sake of inflaming the public against the diners, and they acted appropriately, publishing a refutation of any connection with the author or of any sympathies with its content. The local magistrates moved quickly, and on the 13th published this statement, “Whereas a certain seditious and criminal hand-bill, intending to inflame the minds of the people against Government, was circulated in this town on Monday last, a reward of One Hundred Guineas is hereby offered to any person who will discover either the writer, printer, publisher or distributor, so that he or they may be convicted thereof.” 28

In the summer of 1791, the situation was ripe for conflict. P.B. Rose writes:

It is clear that many of the local clergy and Anglican gentry were convinced with Dr. Samuel Parr, the Whig perpetual curate of Hatton, near Warwick that “things were ripening for a revolution” in church and state. On 22 January 1790 he wrote to warn a friend: ”A storm is gathering, depend upon it…and if the Church does not exert itself it will fall.” The Church did exert itself, however, and a meeting was held at Warwick on 2 February 1790, attended by the “noblemen, gentlemen and clergy” of the county, to concert measures of opposition to repeal. A local committee was also formed to conduct opposition to the dissenters in Birmingham. The pamphlet war continued throughout the year, and in December 1790 relations became so strained that the magistrates obtained the sanction of the War Office for the dispatch of Dragoons from Derby and Leicester, in case rioting seemed imminent. In January 1791 Priestley told Dr. Price: “With respect to the Church, with which you have meddled but little, I have long since drawn the sword and thrown away the scabbard, and am very easy about the consequences.”29

The spark, then, to set off Priestley’s “gunpowder”, was the commemorative French Revolution Dinner. Priestley himself had read the warning signs, and opted to skip attending the event. On the day of the dinner, graffiti of “Destruction to the Presbyterians” and “Church and King Forever” was sprawled across Birmingham, and Priestley’s uncharacteristic display of controversial moderation was definitely a wise one.30 Diners were greeted at three o’clock by insults and were met with mud-slinging when they left the dinner at between five and six o’clock. By eight, “a large and riotous number had again collected, and notwithstanding the attendance of the magistrates, and the conviction that the company had departed, they demolished the windows in front of the tavern.”31 The crowd then proceeded to act like a well-oiled machine, burning and/or destroying the Old and New Unitarian Meeting Houses and the home of Joseph Priestley during the first night.32 The crowd was no mindless rabble, they had clearly practiced discrimination, inflicting damage upon “properties of prominent Unitarians and Quakers, most of them wealthy, some suspect for their “philosophical-radical” associations, others tarnished (in the eyes of the crowd) for their connection with law and justice.” For four days the crowd attacked selected targets, finally being dispersed by Dragoons arriving from Nottingham. 33

Given the organization of the mob, it is a definite possibility that some planning went into the riot. In fact, if the riot was largely motivated by religious controversies brought about by Priestley and his peers, a planned riot would make much more sense. As Catherine Hutton pointed out:

“That this infuriated mob was originally instigated by somebody does not admit of a doubt. Men will assemble and riot for want or oppression, for bread, or for taxes; but what mechanic will leave his labor, and burn his neighbour’s house, because Church and King are in danger from a few gentlemen dining together to commemorate the French Revolution, if such a notion be not instilled into his mind for such a purpose? It is said that emissaries were sent from London to induce the populace to riot…”34

R.B. Rose further substantiates this claim: “An alternative charge, that the riots were the result of an organized local “Church and King” plot rests on a body of evidence which cannot be lightly dismissed. There is a number of more or less significant indications that the rioters acted accordingly to a concerted plan, and that the appearance of mob disorder merely masked the activities of a disciplined nucleus of determined arsonists.”35 While it is not the purpose of this paper to determine if the Birmingham riot of 1791 was premeditated, the possibility of a “concerted plan” lends support to the idea that the riots were religiously based. It is difficult to believe that the laboring class of Birmingham would suddenly rise up and expend enormous amounts of energy on destroying those targets they deemed a threat to the Church and monarchy, while carefully avoiding harm to those not considered a threat.

William Hutton, historian, Unitarian, and friend to Joseph Priestley, claimed that five, specific events were to be considered the causes of the riots. In his Narrative of the riots in Birmingham, these five events were: The dispute over the library’s inclusion of Priestley’s History of the Corruptions of Christianity, the attempt to obtain a repeal for the Test Acts, Priestley’s controversial disputes with clergy, the inflammatory hand-bill circulated just prior to the dinner, and, the dinner itself. Hutton too, agreed with his daughter in suspecting organization behind the riots, “Tumultuous crowds seldom rise of themselves, except to redress a supposed grievance of their own, as a scarcity of work, oppressive taxes, a want of provisions, to prevent enclosure, or raise the price of labour. If therefore they do not rise, nothing is plainer than that they must have been raised. "the Church and King" have been put into their mouths, for they knew but little of either.”36

The Priestley Riots were the end result of years of religious controversy mixed with the potential threat of revolution against Church and King. The mob, while possibly following orders, was nevertheless all too eager in attempting to stamp out ideologies (by destroying those buildings associated with them) which threatened political and religious traditions they held dear. Joseph Priestley did most certainly not deserve such destruction of his property and possessions, but by his constant stoking of the fires of controversy surrounding such deep-held beliefs as that of the divinity of Christ, could it be said that he, in a way, asked for it? In his Memoirs of 1795, Priestley wrote that “the clergy, not only in Birmingham, but through all England, seemed to make it their business, by writing in the public papers, by preaching, and other methods, to inflame the minds of the people against me.”37 Priestley was in no way unintelligent, and yet, such was his ignorance concerning the impending threat of physical violence that had it not been for the persuasions of his friends, “he would certainly have made his last exit. The mob solemnly cut off his head in effigy.” 38

Works Cited

1. George Rude The Crowd in History, 1730-1848 (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1964), pg. 143

2. Ibid, 142.

3. G.I.T. Machin “Resistance to Repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts, 1828,” The Historical Journal Vol. 22, No. 1, (Mar. 1979) pg. 120.

4. G.M. Ditchfield, “The Parliamentary Struggle over the Repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts, 1787-1790,” The English Historical Review, Vol. 89, No. 352 (July 1974), pg. 551.

5. Rude, The Crowd in History, pp. 145-146

7. Joseph Priestley An History of the Corruptions of Christianity, in two volumes (Birmingham, 1782, Vol. 1. Eighteenth Century Collections Online), pg. 3.

8. R. E. W. Maddison and Francis Maddison “Joseph Priestley and the Birmingham Riots,” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 12, No. 1 (Aug 1956), pg. 99.

9. Isabel Rivers and David Wykes Joseph Priestley, Scientist, Philosopher, and Theologian (London: OxfordUniversity Press, 2008), pg. 10.

10. Joseph Priestley A letter to the Right Honourable William Pitt, , First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer; on the subject of Toleration and Church Establishments; occasioned by his speech against the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts, on Wednesday, the 21st of March 1787 (London, 1787, Eighteenth Century Collections Online).

11. R.B. Rose “The Priestley Riots of 1791,” Past and Present, No. 18 (Nov 1969), pg. 71

12. Ibid, 71.

13. Maddison and Maddison, “Joseph Priestley and the Birmingham Riots,” pg. 99.

14. Madan, Spencer. A letter to Doctor Priestley, in consequence of his "Familiar letters addressed to the inhabitants of the town of Birmingham, &c." occasioned by a sermon preached…by the Rev. Spencer Madan. (Birmingham, 1790. Eighteenth Century Collections Online), pg. 2.

15. Madan, Martin, Letters to Joseph Priestley, LL.D. F.R.S. occasioned by his late controversial writings. By the Rev. M. Madan. (London, 1787. Eighteenth Century Collections Online), pg. 9.

16. Joseph Priestley Familiar letters, addressed to the inhabitants of Birmingham, in refutation of several charges, advanced against the Dissenters and Unitarians. (Birmingham, 1790, Eighteenth Century Collections Online).

17. Roy Porter The Enlightenment, (Macmillan, 2001), pg. 409.

18. R.B. Rose, “The Priestley Riots of 1791,” pg. 71.

19. Rude, The Crowd in History, pg. 145.

20. E. Robinson “New Light on the Priestley Riots,” The Historical Journal, Vol. 3, No.1 (1960), pg. 73.

21. Ibid, 73.

22. Ibid, 73.

23. Joseph Priestley The importance and extent of free inquiry in matters of religion: a sermon, preached before the congregations of the Old and New Meeting of Protestant Dissenters at Birmingham. November 5, 1785. To which are added, reflections on the present state of free inquiry in this country. (Birmingham, 1785, Eighteenth Century Collections Online), pg. 40.

24. J.D. Bowers Joseph Priestley and English Unitarianism in America, (Penn State Press, 2007), pg. 138.

25. John Money Experience and identity: Birmingham and the West Midlands, 1760-1800 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1977), pg. 126-127

26. Rude, The Crowd in History, pg. 146.

27. Anonymous Author. An authentic account of the riots in Birmingham, on the 14th, 15th, 16th, and 17th days of July, 1791; also, the judge’s charge, the pleadings of the counsel, and the substance of the evidence ... (Birmingham, 1791. Eighteenth Century Collections Online), pg. 1.

28. Ibid, 2-5.

29. Rose, “The Priestley Riots of 1792,” pg. 72.

30. Ibid, 73.

31. Anonymous Author. An authentic account of the riots in Birmingham, on the 14th, 15th, 16th, and 17th days of July, 1791, pg. 5.

32. Ibid, 5,6.

33. Rude, The Crowd in History, pg. 143.

34. Maddison and Maddison, “Joseph Priestley and the Birmingham Riots,” pg. 102.

35. Rose, “The Priestley Riots of 1792, pg. 78.

36. William and Catherine Hutton The Life of William Hutton, F.A.S.S.: Including a Particular Account of the Riots at Birmingham in 1791, and the History of His Family

(Published by Baldwin, Cradock and Joy, 1816: Original from University of Michigan, Digitzed March 4, 2006), pg. 169.

37. Maddison and Maddison, “Joseph Priestley and the Birmingham Riots,” pg 99.

38. Rose, “The Priestley Riots of 1792, pg. 84.