Mary Celeste

Mary Celeste

A ship that was found drifting in the Atlantic Ocean just off the coast of Portugal, with no crew on board her was towed into Gibraltar and an enquiry into her mysterious circumstances was set up.

She was a two mast brigantine 103ft long, weighing 282 tons, made in Nova Scotia's Spencer Island Canada, and she was registered firstly as the Amazon, and later as the Mary Celeste.

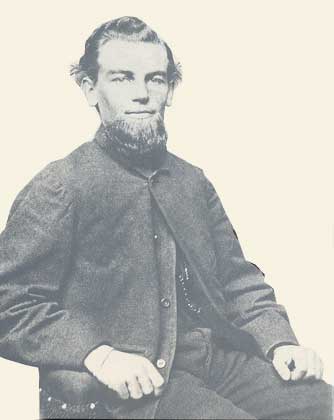

She was called an unlucky ship as her first Master died after her maiden voyage and she later ran aground on Cape Breton. The registered owners were James H Winchester, Sylvester Goodwin and Benjamin Spooner Briggs. Benjamin Briggs a man of known sobriety and good judgement, became the new Master under her new name of Mary Celeste. Her crew of seven were first class sailors and she was carrying a cargo of 1,700 barrels of alcohol to Genoa, Italy, for the fortification of wine. She had been chartered for a return cargo to New York. Briggs's wife Sarah and his daughter Sophie were also on board the Mary Celeste.

Benjamin Briggs

Benjamin Briggs

If it had not been for an up and coming author named Arthur Conan Doyle, who read about the ship and changed her name in his story to Marie Celeste, the mystery of this vessel could possibly have passed unnoticed into the very many other lists of ships that were similarly found drifting in those latitudes. But Arthur Conan Doyle's story was a great hit with Victorians and it became legend.

Mary Celeste sailed from New York's east river on November 7th 1872 and set sail for Genoa. She was spotted drifting by the crew of the ship, Dei Gratia on their port bow about five miles away, on December 5th. Captain Morehouse on Dei Gratia knew Captain Briggs and had dined with him a few days before she sailed. Dei Gratia sailed a week after Mary Celeste.

Mystery

Through his telescope Morehouse could

see the ship slowly drifting in a moderate breeze, her sails not set

for the gale that she must have passed through during the previous

few days. Dei Gratia came to her side to offer assistance if Briggs

needed it. Taking a small boat Oliver Deveau Chief Mate and two men

rowed towards the drifting ship and boarded her.

Not a living soul

could be seen. Two of the hatches were off and her compass had been

damaged while the ship's wheel was loose. The sextant and chronometer

were missing.

The ship was awash with water even between decks.

The Captains navigational equipment had vanished along with the

register, but the Captains ceremonial sword was still in the cabin

showing some signs of staining on the blade. All their clothing and

child's toys were found . Some things seemed to be in order, with

about five months worth of food and water still unused. Sarah's

harmonium and sheet music were still in place and a few charts lay on

the bed as if thrown aside in a hurry.

A broken clock hung upside

down on a wall, washing was hanging on a line nearby. Oilskins,

boots, pipes, seaman's equipment were scattered about. In the Mate's

cabin, charts up to November 24th and a log showing a time of 08.00

on the 25th had been marked. The last marked point on the chart was

600 miles away from her present position. The chronometer, sextant

and registration papers were missing.

Had she been at the mercy of

wind and waves for 600 miles from that last marked position?

One

of the two pumps was in good working order, well enough to clear the

remaining three and a half feet of water. On the whole she was fit to

sail.

The three men who were delegated to sail her into port to

claim salvage found her fairly trim and manageable, and she entered

Gibraltar at 9am on Friday the 13th December 1872.

In the

Admiralty Court, in his conclusion the Judge praised the crew of the

'Dei Gratia' for their great courage and the great skill shown in

bringing both vessels safely into Gibraltar.

Many theories were rampant about the mystery. One was that for some reason the Captain and crew panicked and took to the ships boat. This could have been due to a mistake in sounding the bilges and thinking she was sinking, or bearing in mind the nature of the cargo, there may have been an small explosion or rumbling in the cargo. We do know that when the cargo was finally unloaded in Genoa nine barrels were found to be empty, but there were no signs of an explosion.

Maybe Briggs ordered his men to abandon the Mary Celeste, snatched up his navigational instruments and they left in great haste, later to be drowned when their boat capsized in bad weather. It may be significant that the main halyard, a stout rope, 3 inches in circumference, was found later broken and hanging over the side.

Admiralty Court

The court in Gibraltar settled the case as a mystery. They were more concerned in ownership of the Vessel and the cargo, rather than solving another unknown, tragic loss. They were well used to this happening in the Atlantic. The same pattern had emerged over many years, and among others, in April 1849, a Dutch Schooner 'Hermania' was found dismasted but otherwise sound, with the Captain, his wife, child and crew missing, and again in February 1855 the 'Marathon' was found in perfect order but totally abandoned.

Conan Doyle's story was meant to excite the imagination into

forming theories and explanations, which it did, a few wildly

exaggerated stories helped to popularise it, adding to the mystery.

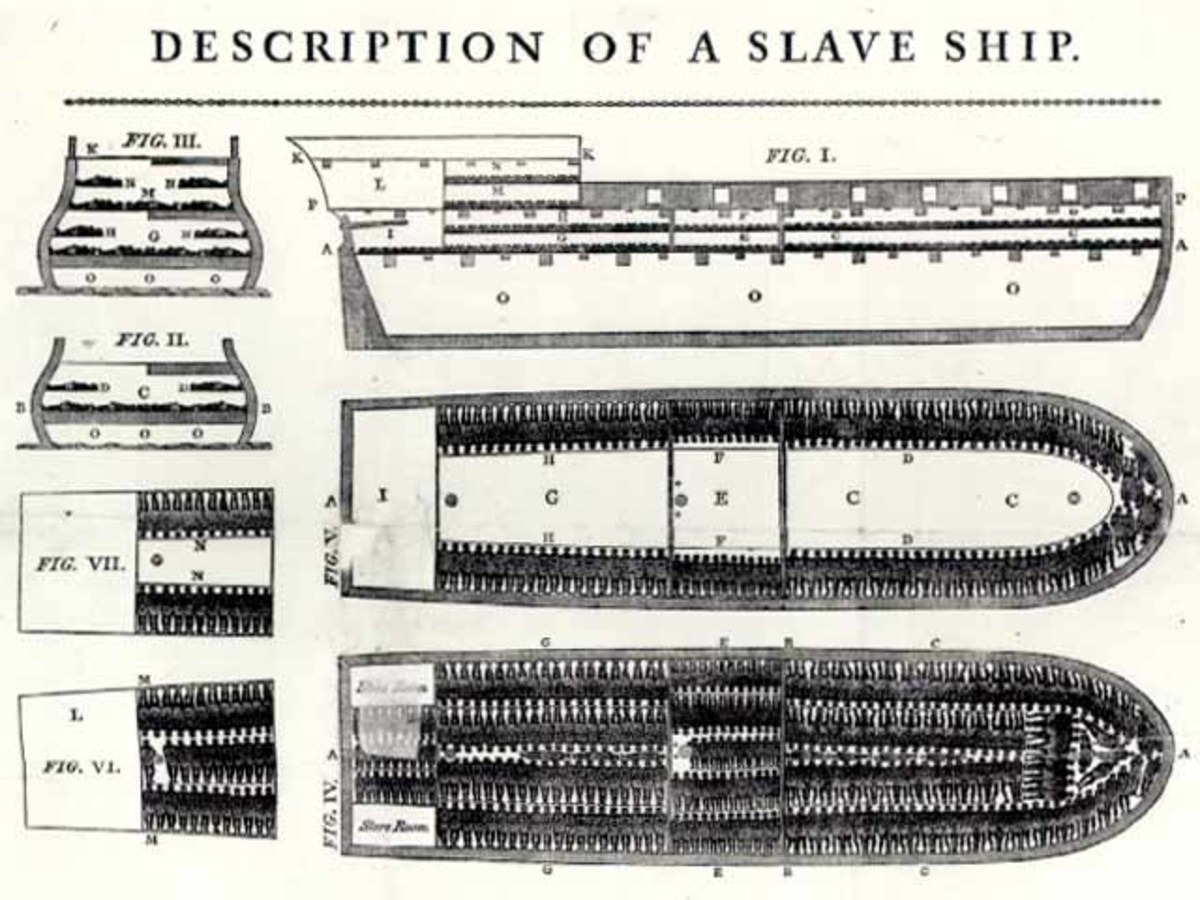

I have my own theory. It's a theory based on fact. The fact

being that slavery was still in full swing at the time of the

disappearance of the people from the Mary Celeste. Slavery was still

a very lucrative business in 1872. People were worth much more than

some other commodities.

The slave trade went back hundreds of years. It was not only the British who were big in the capture and selling of slaves. After the abolishment of slavery in Britain, the corsairs from the Barbary coast of North Africa voyaged as far as Iceland to capture people from the countries on this enormous sea route. Slaves were taken from France, England, Ireland and Scotland.

There is a lot of archived material on the Corsairs of the Barbary coast. These were muslims from Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco who scoured the Atlantic for easy targets, taking slaves from captured ships.

The Corsairs raided the Cornwall and the North Devon coast in the 17th and early 18th Centuries. These Barbary Pirates were based mainly at Sale near Rabat in Morocco. At one point they had occupied Lundy Island and flew the flag of Islam there while they raided the coastal harbours and villages for women and children as slaves, and captured ships and their crews. Crews of ships were more valuable than the cargo as far as these raiders were concerned, as they had a higher market value as slaves. 3,000 people were enslaved from this small corner of the United Kingdom in 1640, alone, and to this must be added many more snatched from the Biscay coast, Portugal, and Spain. Thomas Pellow, a boy aged 11who was a cabin boy on his uncle's ship was captured by Barbary pirates off Cape Finisterre spent 23 years before he finally escaped and returned home to Cornwall where he wrote his memoires. If his story is typical of others of this period it would have been particularly difficult to survive, let alone escape.

Thomas Pellow's story is fascinating. The boy found himself a slave to the son of the notorious Sultan Ismail, whose habit was to personally decapitate his slaves on a whim. Later when the son was himself decapitated Thomas passed to the Sultan. Only his quick wit and his ability to ensure that he stayed clear of the Sultan's killing rages allowed him to survive. He was flogged until he converted to Islam, but when he finally managed to escape, he renounced Islam.

It was not until the 19th Century that the Barbary pirates were defeated. As late as the 1790's Barbary Pirates were seizing ships in the Channel and the entrance to the Irish Sea, and fishermen and coastal traders were being carried off as slaves. European powers agreed upon the need to suppress the Barbary pirates. The sacking of Palma on the island of Sardina by Tunisians, where 158 people were captured raised fury. The Congress of Vienna called on the United Kingdom to act for Europe, and in 1816 Lord Exmouth was sent to Tunis and Algiers to obtain treaties. His visit was succesful and produced diplomatic documents and promises. He sailed back to England in triumph, but while he was celebrating, a number of British subjects had been brutally treated at Bone in Algeria. He was sent back, and on August 17, in combination with a Dutch squadron he bombarded Algiers. The lesson so terrified the pirates of Algiers and Tunis that they gave up over 3,000 prisoners and made fresh promises. A short time later, however, Algiers renewed its piracies and slave-taking, and the steps to be taken were discussed at another congress in 1818 but it wasn't until 1824 that another British fleet under Admiral Sir Harry Neal again bombarded Algiers. When France conquered Algeria in 1830 she boasted that the Barbary Corsairs had been driven out. But where were they driven to?

Theory

Morocco and the west coast of Africa still carried on with piracy. The king of Dahomey a West African state in 1840, stated that : ' The slave trade is the ruling principle of my people. It is the source and the glory of their wealth…the mother lulls the child to sleep with notes of triumph over an enemy reduced to slavery…'

So my theory is that pirates were still operating in the Atlantic at the time of the Mary Celeste mystery. Although the Royal navy patrolled the Straits of Gibraltar and the seaway leading to it, they could not cover all of such a vast area all the time, and pirates were able to avoid them. The pirates boarded Mary Celeste, captured the crew and took it in tow. During a storm the tow rope parted as evidenced by the 3 inch rope trailing in the water, and as humans were more valuable than ships or cargo, the ship was left to its fate. Well, it's a theory to add to the already long list of theories.