- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era

Napoleon in Exile: St. Helena

The End of a Dream

A Bitter Defeat

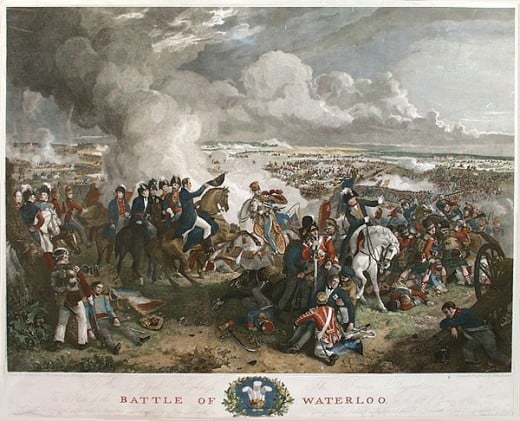

On the blood soaked battlefield of Waterloo, Napoleon’s final dreams of empire, glory and conquest came to a shattering end. The defeat at the hands of the British and Prussians resulted in a second and final abdication as Emperor. For the tens of thousands of soldiers who had somehow survived the near two decades of war, the time had finally come to head to whatever was left of their homes. For the former Emperor however, the situation was infinitely more complex. He had of course the option of surrendering and relying on the magnanimity of his enemies, or attempting an escape. The idea of sanctuary in America crossed his mind more than once.

Within a week of Waterloo, his former Minister of Police, Fouche wrote letters to both Wellington and the British Foreign Minister asking for passports to enable Napoleon to reach America safely. Unsurprisingly, any acquiescence was not forthcoming.

The One That Got Away

Plans of Escape

As the days turned into weeks, the thought of slipping away to America seemed to grow ever more appealing. Despite the fact, that all French ports were under heavy blockade by British ships, strenuous efforts were made to get him away. At Rochefort, two frigates were put on special alert to expect the Emperor’s arrival imminently and on the 29th June, Napoleon left Paris bound for Rochefort. After narrowly avoiding a Prussian detachment he arrived safely.

However, if the escape had seemed improbable before, the scene that greeted the Emperor at Rochefort lowered expectations further. There were quite simply too many obstacles blocking any possible escape. Napoleon’s delegation attempted to moot some rather wild propositions, which included shutting him in a barrel, supplying a few holes for breathing and placing him on a neutral ship, ideally an American ship. But Napoleon had once been lord of an Empire that had stretched eastwards as far as Moscow, and he would not be subjected to life inside a barrel, also he would not take the risk of being captured by his enemies. Instead, being a proud soldier, he chose to surrender with honour, and place himself under his enemies’ protection; as an enemy officer he was entitled to be treated in accordance with the rank he held.

Truth be told, the life of a private citizen held very little appeal for Napoleon. Interestingly his brother, Joseph had offered to masquerade as the Emperor while hiding out on the Basque islet of Aix. The idea was that Joseph’s ruse would allow Napoleon to slip away and escape safely to America. Napoleon however, chose to decline this sacrifice, and instead it was Joseph that slipped away on a boat bound for America.

The Man Who Accepted an Emperor's Surrender

On Board the Bellerophon

Surrender and Exile

On the 15th July 1815, Napoleon surrendered to a Captain Maitland on board HMS Bellerophon, a 74 gun warship that had seen action at Trafalgar. Stepping on board, he proudly declared: ‘I come to throw myself on the protection of your Prince and your laws.’ The British officers must have been uneasy, but they upheld their duty bound honour and served Napoleon with an English breakfast, which he reputedly disliked. In all the time that he was in captivity, he regarded himself as a guest rather than a prisoner. The Bellerophon made sail for England, but Napoleon was strictly forbidden from leaving the ship under any circumstance. The British Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool contemplated on a destination for Napoleon to serve his exile, and the only suitable place that crossed his mind, was the tiny isolated volcanic island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic, almost 1800 miles from the South American coast.

In Torbay, and then Portsmouth, news of Napoleon’s presence generated great excitement among the locals. Crowds of sightseers clambered into small boats to catch a glimpse of the man who had ruled over much of Europe for a generation. Napoleon himself loved the attention and encouraged the building hysteria by appearing on deck frequently and tipping his hat to any well dressed woman he glimpsed. At Plymouth, frigates were positioned on either side of the Bellerophon, and guard boats were deployed to ram and buffet the encroaching tourist crafts. One was capsized, resulting in the tragic drowning of one of the occupants. The local militia fired musket volleys into the air in an effort to dispel the thickening hordes, but the crush grew worse. On the 30th July, roughly a thousand craft bobbed and jostled around the warships. Seaman onboard the Bellerophon erected a huge blackboard, upon which Napoleon’s daily activities were recorded meticulously: ‘At breakfast,’ ‘In his cabin,’ ‘Dictating to his officers,’ or ‘Coming on deck’ were among the brief but informative bulletins posted.

Catching Sight of an Emperor

Napoleon's Final Home

A Useful St. Helena Link

- St Helena Tourism Official Website

All of the information regarding tourism on St. Helena.

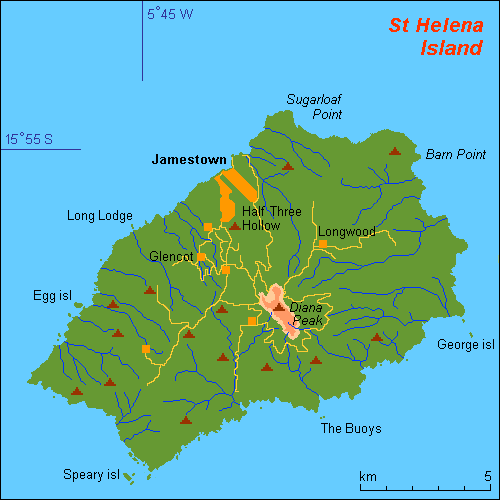

St. Helena

Before telling of Napoleon’s tenure on St. Helena, I shall take a moment to tell you a little more about the island. As already mentioned, St. Helena is an isolated volcanic island in the South Atlantic, nearly two thousand miles distant of the nearest land, the South American coast. When viewed from the sea, it appears as a huge barren rock, rising sharply from the waves. It was originally discovered (uninhabited) by a Portuguese sailor in 1502. For just over 100 years, the Dutch laid claim to the Island, but abandoned it in 1651, after which it was appropriated by the British East India Company, who kept it until passing it onto the British crown in 1834.

While Napoleon was exiled there, its garrison was well stocked with British troops and the governor was one Sir Hudson Lowe. The island’s capital, Jamestown lies in a narrow valley between two masses of rock (Ladder Hill and Rupert’s Hill). Lord Wellington stayed on the island for a fortnight in 1805 while on his way back from India remarked that ‘the interior of the island is beautiful and the climate apparently the most healthy I have ever lived in.’

When the former French Emperor arrived in 1815, its population consisted of 776 whites (mostly British), 1353 slaves, 447 freed slaves and 280 Chinese. The local garrison normally stood at 1000 men, but was doubled during Napoleon’s stay. Later on, St. Helena was used to accommodate Boer prisoners during the Second Boer War (1899-1902), it also served as home for exiled African chiefs and even an ex Sultan of Zanzibar. To this day, it remains a British dependency.

Longwood House

More on Napoleon and his Exile

Napoleon's Time on St. Helena

Napoleon was brought to St. Helena in October 1815 by HMS Northumberland. The officers, who regularly dined with the Emperor on board, were said to be startled by his eating habits, which coupled with his sedentary lifestyle on the island may have helped to hasten his death. Apparently he ate every dish with his fingers, instead of a fork, and seemed to favour the rich dishes, passing up any offering of vegetables.

Upon arrival, he was given a modest residence known as Longwood House, which had previously served as the summer house of the governor. He was given his own very personal household of twenty seven people, all of whom were non British. He had six officers, along with their families, plus fifteen domestic cooks, including valets, cooks, grooms and coachmen.

To describe Napoleon’s stay on St. Helena as unhappy is rather an understatement. Apart from the fact, that he was growing increasingly ill (the medical men who examined him regularly noted his pale features, excessive perspiration, and an alarming gain in weight- largely through lack of exercise and his fondness for cream pastries and claret) Napoleon also detested the governor, Sir. Hudson Lowe who assumed his position in April 1816. In their one and only meeting, Napoleon lost his temper and insisted that the two men should never meet again. In his final years, the former Emperor enunciated ten grievances against the British government, which are as follows:

- Detention: He objected to being treated as a prisoner of war.

- Location: He objected to the isolation.

- Climate: He claimed that the climate was unhealthy.

- Longwood House: He claimed it was inadequate.

- Sir Hudson Lowe: The two were simply incompatible.

- His title: He objected at being referred to as ‘General Bonaparte’ and wished to be called Emperor.

- Limits: He objected to restrictions on movement placed on him by the British.

- Visitors: There were frequent disagreements about the issue of visitor passes to Longwood.

- Correspondence: He demanded freedom of correspondence. When this was refused, he resorted to sending secret letters to Europe via obliging ship’s captains.

- Provisions: He objected to the strict budget restrictions imposed on his staff and food.

Napoleon's Final Resting Place

A Couple of Interesting Links

- How Did Napoleon Die? - Softpedia

An interesting article on Napoleon's death. - BBC NEWS | Health | Napoleon 'killed by his doctors'

Over-enthusiastic medics - not cancer or murder - may have caused of Napoleon Bonaparte's death, researchers suggest.

Napoleon's Death

Napoleon Bonaparte died on the 5th May 1821, aged just fifty one, but in truth, the death had been expected. Napoleon had been sick for at least two years beforehand. The final seven weeks of his life were spent in agony from a lingering pain in his stomach, thought until recently to have been cancer. His long illness had not been helped by a succession of incompetent doctors who simply diagnosed things like liver disease, hepatitis and various stomach disorders, aggravated by the tropical climate.

However, the truth seems to present itself when we examine the actions of a semi qualified Corsican ‘doctor’ named Francesco Antommarchi. He had previously been the assistant of a prominent anatomist in Florence, in which he had supposedly learnt the practice of dissecting corpses. In late March 1821, Napoleon complained of a knife like pain in his abdomen. Antommarchi implored him to take doses of tartar emetic which brought on a period of heavy vomiting. The suffering was unbearable for him, and he refused any more treatment. So Antommarchi resorted to disguising the emetic as lemonade. Despite his failing health, Napoleon remained sharp enough to suspect foul play and viewed the glass with suspicion before handing it to his courtier Montholon. As expected, Montholon was instantly and violently sick, prompting Napoleon to turn furiously on Antommarchi, branding him ‘an assassin’. After this, Napoleon lost all confidence in medicines, exclaiming that he did not wish to have two diseases, one due to nature and the other to medicine.

Recent evidence seems to further vindicate the notion that Napoleon was killed through gradual arsenic poisoning rather than cancer. One of the most compelling pieces of evidence was the fact that Napoleon was grossly overweight when he died. Almost all people who succumb to cancer are actually severely underweight. More evidence came to light, seventeen years after his burial, when his body was exhumed. All who beheld the body noted the remarkably good condition it was in. The arsenic had helped to slow the decomposition process; in fact many biologists use it to preserve animal specimens to prepare them for museum display.

In the 20th Century, a preserved sample of Napoleon’s hair was submitted to the FBI’s top expert in arsenic testing, and the results were positive. There were traces of arsenic, more than 20 times over the normal limit, and seemed to vindicate the poisoning theory. The evidence seems to show that the arsenic (probably slipped into his wine) was designed to kill the Emperor slowly by breaking down his health. Shortly before his death, Napoleon was administered calomel to try to relieve his constipation and orgeat to relieve his unquenchable thirst (both telltale signs of arsenic poisoning). These ‘medicines’ actually combined in his stomach, creating mercury cyanide that ultimately caused his death. Much of the evidence gathered, points the finger of blame squarely at his courtier, Montholon.

Napoleon soon realised that his days were numbered, by the end he was virtually delirious, but in one brief return to normality he declared: ‘When I am dead each one of you will have the sweet consolation of returning to Europe. You will see your relations and your friends; as for me, I shall rejoin my comrades in the Elysian Fields...they will come to meet me; they will talk of what we have done together...We will talk of our wars with Scipio, Hannibal, Caesar and Frederick. There will be pleasure in that.’

On the evening of the 5th May, just after the sunset gun had fired, his time had come. The Emperor’s mouth fell, the eyes opened and the shallow breathing ceased forever. They covered his body with the cloak he had worn at the Battle of Marengo twenty years earlier, on top of that a crucifix was reverently placed and by his side they placed his sword.

Four days later, he was buried among the willow trees near Hutt’s Gate in the centre of the island. He was dressed in his favourite uniform, the Chasseurs of the Guard, along with all of his decorations, white breeches, long boots and spurs. The procession was one third of a mile long, and included his famous horse, ‘Sheikh’. Twenty four grenadiers representing every unit in the procession carried the coffin to his graveside, where his Marengo cloak and sword were removed. Three musket volleys, a 33 gun salute and a minute’s gunfire from the ships in the harbour accompanied the laying of the tombstone and the filling of the grave.

Twenty five years later in December 1840, Napoleon got his wish and was returned to France and interred at Les Invalides. His last parade took place on the 15th December; the hearse transported in a horse drawn carriage paraded down the Champs-Elysees, under the Tricolour and glorious Imperial Eagles. The hearse was followed by ageing veterans of the Imperial Guard still loyal to their Emperor, as well as veterans from Belgium and the Rhineland. For one last time, the guns crashed and the crowds cheered, lost in a wave of nostalgic memories, from a time when France came perilously close to ruling the world.