Project Management Success: Best Practices in Scope Definition

Clear Scope Equals Project Success

I've taught over 300 classes in project management, and in every class, we agree. A project with well-defined scope and goals is headed for success. A vaguely-defined project is headed for disaster. This article teaches you how to define scope well.

Defining Scope Clearly, and Getting Customer Commitment

Imagine playing football, only someone keeps moving the goal posts. Even the greatest football team in the world couldn't be sure of winning. Managing a project to success when success, that is, project scope, is not clearly defined, is like playing football with moving goal posts. We can't win, and neither can our customers.

Project Scope Management is the most important of the Nine Areas of Project Management. So, if we want to improve as project managers, learning best practices for defining scope is a great place to start. For our projects to succeed, scope must be clearly defined in many different ways, and then further refined to an engineering level of precision. Read on to learn how!

Steps to Excellent Scope Definition

The essential best practice for scope definition is to think like an architect in defining project scope. We do this in two steps:

- Define scope from several different perspectives with eight questions.

- Apply architectural thinking to the scope of your project.

Once these core best practices are clear, we move forward with these steps:

- We find all customers and stakeholders.

- We elicit requirements from them.

- We define scope precisely, so it is objective and measurable.

- We detail out our scope definition over time using progressive elaboration.

Each of these steps is explained in this article. And each also has a best practice of its own. If you want to learn them in more detail, check out the links in the sidebar: Detailed Best Practices for Scope Definition.

When we have defined scope as well as an architect and a team of engineers make construction plans for a project, we can complete the project plan and manage scope to success at the lowest possible cost, with the soonest delivery date, and with the best features and quality.

More About Scope in General

This is an advanced article on the best practices of project scope definition. If you are new to project management, you may find it easier to read some of my other articles first. Here's a brief guide:

- How to Lay Out a Project Management Plan is the best place to start. It introduces all nine areas of project management, including Project Scope Management.

- Read Project Scope Management: What Are We Making? for a clear understanding of the full process of Project Scope Management. This article, about Scope Definition, is an early step in the whole process.

- Even after scope is defined using the tools in this article, the customer may try to move the goal posts. Learn how to handle this problem by reading Project Success: Manage Scope Creep and Customer Expectations.

Detailed Best Practices for Scope Definition

This article explains why and how to think like an architect. To drill down even more and learn to work like an architect to define project scope, please read these additional articles:

- Use Customer and Stakeholder Identification for Project Success to find all of your customers.

- Read Requirements Elicitation for Project Success to learn how to find out what your customers really want.

- Learn how to define goals clearly enough so that they can be measured in Measurable Goals: Requirements Definition for Project Success.

- Don't get bogged down in planning, lost in paralysis by analysis, or doomed by vague ideas: Use Progressive Elaboration for Project Success.

The Eight Questions of Scope

Before we can create a time and cost estimate to predict long a project will take or what it will cost, we need to know the answers to eight questions. (Five of these will be familiar to students of journalism, as they are the basics of any good newspaper article.)

- Why are we doing this project? What is it's purpose and value? (To better understand the many meanings of the question "Why?" please read this article on The Five Whys.)

- Where are we starting? (This is called the initial situation.) And where will we be when we finish? (This is our first picture of our goal.)

- What are we making? What will it look like? What is the goal? (This will get refined more clearly later on through Progressive Elaboration.)

- How will we make it? Will be built it from scratch, or buy something off the shelf and customize it?

- Who is the customer? Who are the stakeholders? Who is doing the project?

- When will we do it? When do we start, when will we deliver? How long will it take? How much effort will it take?

- How much will it cost?

- Whether we will go ahead or not? Is it better to cancel the project?

The simplest first step is to write down each of these questions, close your office door, and write answers to each one. Or, some people prefer to write freestyle everything we know about the project, then break up what we wrote into answers to each of the above questions.

But our own answer isn't enough. Once we know who is the customer, and who the stakeholders are, we have to include everyone's ideas about the project in one answer. And that one answer is the project scope statement we all agree on. The process of getting everyone involved in creating one answer used an architectural perspective and is called requirements elicitation.

Architecture in Multiple Perspectives

Scope and Architecture

Most people think that architecture is about designing buildings, and, indeed, that is one type of architecture. But the term has been extended to include urban design, landscape architecture, the architecture of information systems, and the act of designing or re-designing any type of system. Every project creates a component of a system and alters a system, so thinking like an architect is an essential step in every project. The unique skill of an architect is the ability to communicate with each person on a project - each customer or stakeholder - in his or her own language, and address his or her concerns. A construction architect will show clients a computer rendering of their new home, show the contractors blueprints, and show the financial manager a budget. The architect makes sure that these different pictures all match up to the same project plan. We do the same as project managers.

We define the project so that everyone understands it. Say we are designing a new corporate headquarters for a company after a merger. We want to understand the perspective of every customer:

- The Board of Directors and C-level executives want a building that, inside and out, reflects the image and success of the company.

- The Chief Financial Officer wants costs controlled.

- Each head of a division wants enough space and all the proper tools for his or her staff.

- The IT department wants every room connected to all the offices of the company with the latest in video conferencing.

- The head of marketing wants a way to meet the press, while the head of security doesn't want the press allowed inside the building.

Meanwhile, the technical people each need their own picture: The architect; the general contractor; the plumbers; the electricians; the interior designer all have their own perspective and their own questions. There are peripheral stakeholders as well: Building inspectors require that the building to be up to code, and neighbors are concerned about walls, fences, and construction noise. It is up to the project manager to create one definition of the whole project, give each person a clear picture that he or she will understand, and resolve conflicts that arise from different perspectives.

Remember, also, that each person speaks a different language and needs a different picture:

- The chief financial officer wants spreadsheets. \

- The head of security wants floor plans and blueprints.

- The director of marketing wants a 3D video walk-through of the meeting rooms.

As the project manager, we need to be able to listen to, create plans and pictures for, and come to agreement with each player in his or her own language. And, as we do this, we return to the eight questions about the project, getting answers from each customer and each stakeholder.

This is hard to do even on a small project. And it gets harder when we're building something that people can't see and touch, like an improved business operations system.

We do the work of architecture by meeting with each customer and stakeholder, eliciting requirements, defining scope and features precisely, and coming to agreement about scope.

Finding All Customers and Stakeholders

Finding all your customers may sound easy, but it's not. I worked for the IT department of a city university that acquired two floors of an adjacent building for expansion purposes. There was a project team that was cutting a doorway and building a ramp to go from one building to the other. They talked to the people moving into the new floors; they talked to the people who would get a new student corridor through their offices; they talked to the guy who wired the telephones; they got permission from the fire inspector and building inspectors. But they never talked to anyone about computer cables!

Just before the project was about to happen, I learned about it. I was the Cable Guy back then. I went to my boss to find out if we could put some computer cables through to the new building. It wasn't easy - changing plans after the fire inspector has approved them is a real challenge. In this case, we pulled it off. But I've seen other projects fail because a project manager didn't find internal stakeholders - people who needed to know about the project.

We find stakeholders we might have missed by taking our answers to the eight questions and open up an organizational chart, and then asking, "Who needs to know about this?" We don't just ask ourselves. We ask everyone on the project, "Who needs to know about this?" And then we go talk to them. It is better to look silly and have ten people say, "I couldn't care less about your project!" than it is to miss one crucial stakeholder. To learn more about finding internal stakeholders, please read Customer and Stakeholder Identification for Project Success. If you are developing a product or service for sale, you can learn about customer identification in marketing by reading Marketing for the Solopreneur One-Person Business.

Introducing Requirements Elicitation

Requirements elicitation is a whole field of study in itself, worth a large book. The key concept is this: It is naïve to think that a customer can tell you what he or she wants. People are not trained in how to imagine future products or services, and then define them clearly.

The solution is that we have to train ourselves to ask the right questions so that we can get the right answers from them. We need to deliver pictures, prototypes, and more. We need to engage the customer or stakeholder in what the product or service will be like for them. And then we need to get their answers to the eight questions we introduced above.

To learn more, please read Requirements Elicitation for Project Success.

Defining Scope Precisely: Inclusions and Exclusions

If we only define what we are doing on the project, then we will not define it with enough clarity and precision, and our project will run into trouble down the road. We also need to define what we are not doing.

There are two reasons for this. One is about customer expectations, and is fully explained in this article about managing customer expectations and scope creep.

The second reason is more technical. It is about the engineering process of creating a good definition: Anything is defined more clearly when we way what it is, and also what it is not.

When we clearly define what something is and also is not, we take one step towards objective, measurable requirements. When we have objective, measurable requirements, then all the bickering ends. All the vague puttering around ends. The project team focuses on a defined goal that we know will delight the customer. And if we make a mistake, everyone agrees on it, and we fix it with no hassle and no blame. Clear definition of desired results creates the optimal project team environment, leading to excellent results, great features, and quality delivered on time and below cost. To learn how to do this, please read Measurable Goals: Requirements Definition for Project Success.

As we define goals clearly, we make sure we have agreement from our customers and stakeholders. That way, we keep everyone on the same page and manage customer expectations as we drive towards success.

Progressive Elaboration

Reading through this, some people may think that scope has to be fully defined before work can get started on a project. And, yes, that was the way it was done back in the 1960s, with a project management life cycle system nicknamed "the waterfall." But we've come a long way since then, increasing flexibility through developing our scope definition in a series of stages. The Project Management Institute (PMI) calls this Progressive Elaboration.

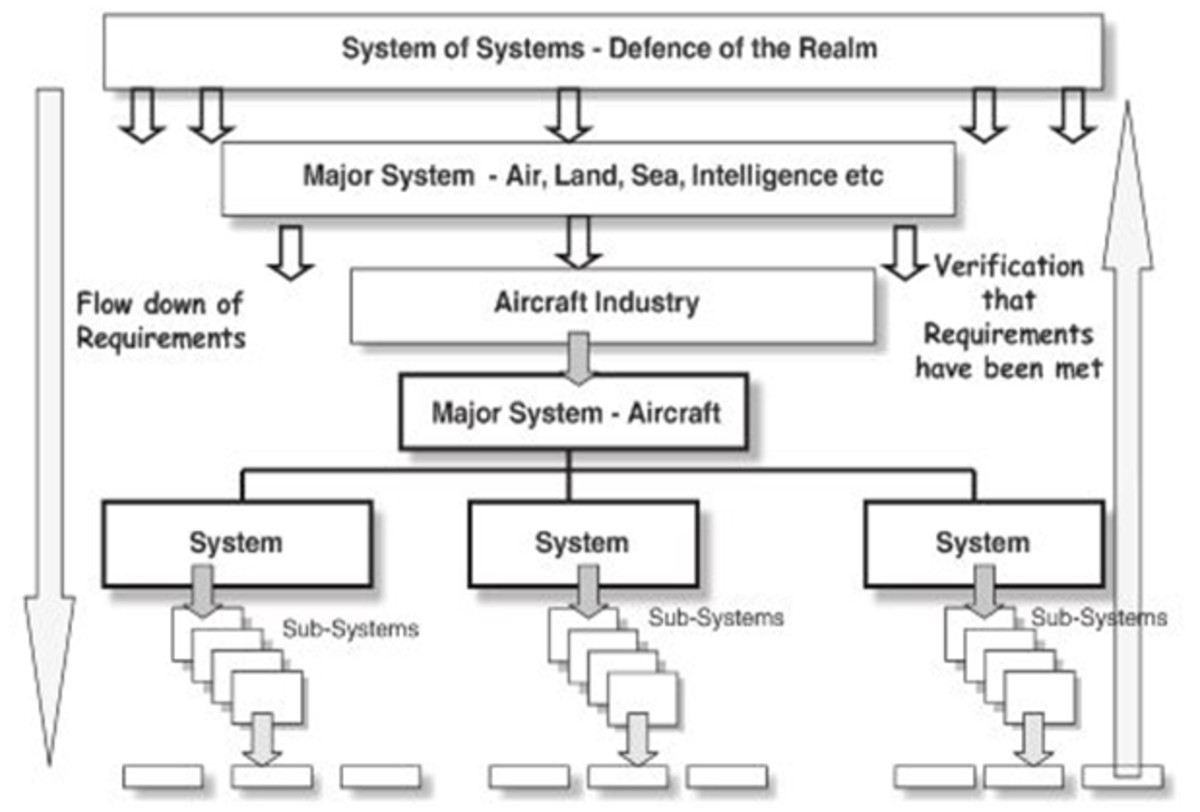

Progressive elaboration is just a fancy term for starting with a clear definition of the big picture, and then working our way down into the details. The key to it is understanding that we can be precise and yet still operate at a high level, without a lot of detail. For example, a very precise scope statement of an airplane might say, "We will build an airplane with one fuselage, two wings, a tail, and flight controls." Each of those components can be described more accurately, either by function or by technical specification. Ultimately, a Boeing commercial jet will be described in over 1 million individual parts. As long as each definition is clear and precise at its own level, we can elaborate the details progressively as we go along.

To learn how to do this, please read Progressive Elaboration for Project Success.

How Well Do You Know Best Practices in Scope Definition?

view quiz statisticsReady for Success

If we include everyone and do all of the above, we can create a clearly defined scope statement for our project. That's the beginning of project success.

We also need to manage the scope after it is defined. A clearly defined scope is like goalposts set in the end zone. But will the customer move them? That's called Scope Creep. And will the customer be happy when you score a touchdown? Not always, but, if they are, that's called Customer Satisfaction. How do we get there? These issues are addressed in another article about managing scope creep.

In addition, planning all the other areas of a project can be done once scope is defined. For example, once we know our starting point and we are making, we can estimate time and cost. We can also plan all nine areas of project the project plan. Scope is the most difficult element of a project to define. Once it is clear, the rest of the plan falls into place through a series of largely mechanical steps, such as PERT estimation.