- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

Reconstruction and the Ex-Slave

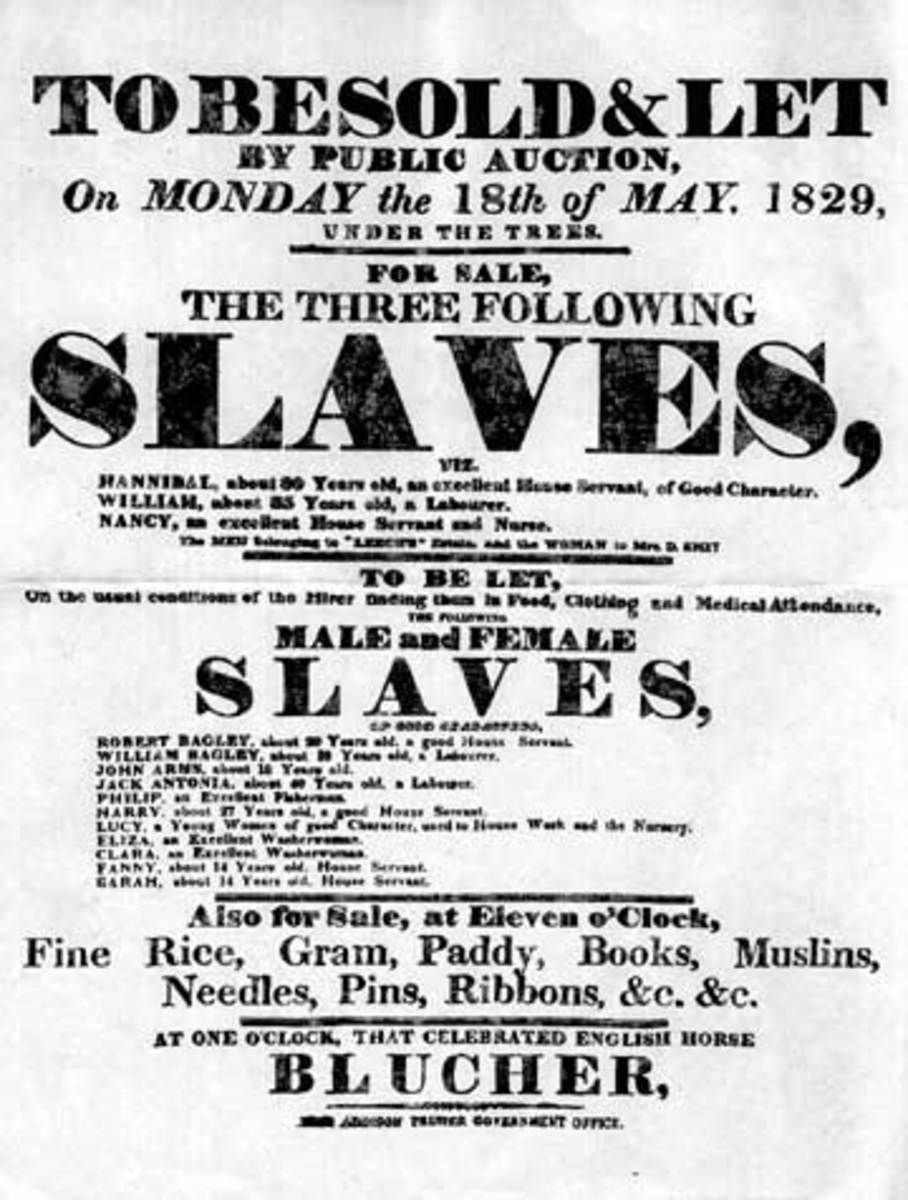

After the surrender of Confederate forces at Appomattox Courthouse in 1865, the American Civil War was at an end. One by one, other commanders surrendered their fighting forces, and after a brief contemplation of continuing guerrilla warfare, the Confederacy was dissolved. The United States Congress was now faced with ominous questions. What was to become of the Southern states? How would they be brought back into the Union? What would be done to help the people living there? And most pressingly, what was the role of ex-slaves in the new Southern society? So began the period known as Reconstruction.

Proclamation and Amendment

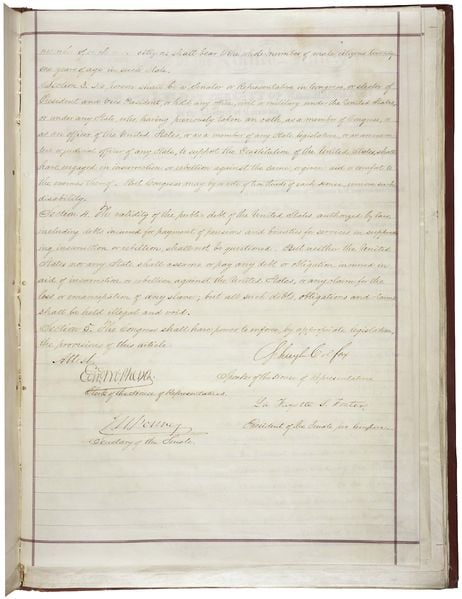

After the Civil War, one of the major issues at stake was the disposition of African-Americans in the rebellious states. Slavery had been abolished in the South by President Lincoln after the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863 through the Emancipation Proclamation. But it was not until 1868 and the 14th amendment that blacks were made citizens, due process was established and participants in rebellion were prohibited from holding elected office. Neither the Proclamation nor the adoption of this amendment created an immediate difference in Southern society. Although slaves were legally free, they were not functional equals to the whites around them. Supported by Northern blacks and abolitionists, ex-slaves began to demand access to land, education and the protection of their voting rights. These demands were strongly opposed by whites in the South and the North, especially poor whites who did not want to think of blacks as equals. This is an important distinction to make -- many people were proponents of African-American rights, but very few whites were ready to publicly state they believed blacks were equals.

The Republican's Promise

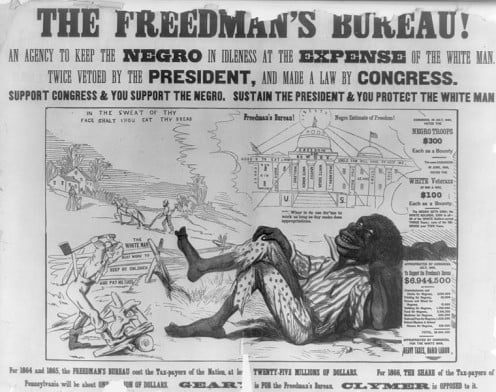

During, and after, the Civil War the Republican party controlled Congress. Like today, there were many different factions within the party. The "Radical Republicans" had promised that freed slaves would receive "40 acres and a mule" from the government after the war because their intention was that large plantations would be broken up into small homesteads and given away. Many freed slaves liked this idea because it was both a means of helping themselves, and revenge against their former owners. They also felt that land ownership would help cement their right to vote. Immediately after the war, the Freedman's Bureau was established in 1865 to assist ex-slaves by providing government assistance. It was intended only to last one year before transitioning into an entity that would fulfill the rest of the Republican's promises.

"40 acres and a mule" was well supported by the Republican party. There were many reasons to seek the break-up of plantations. First, the power of aristocratic owners would be broken if they could no longer accumulate wealth. This would bring about a radical shift in political clout and presumably social change in the South, which many Northerners felt was necessary for Reconstruction. Secondly, the ex-slaves would learn to be self-sufficient farming their own land and become productive members of society. At the South Carolina Constitutional Convention, Rep. Richard Cain stated a common belief of the time, "the possession of lands and homesteads is one of the best means by which a people is made industrious, honest and advantageous to the state...you can give a man a farm so he will eat for today, but teach him to farm and he will eat for a lifetime." Theoretically, self-sufficient blacks would not require financial assistance from the government, and money could instead go towards expanding industry in the South. The acquisition of votes among the black population was also important, and since they had made this promise, the party wanted to fulfill it, keep the ex-slaves happy, and keep them voting Republican.

Resistance to the Promise

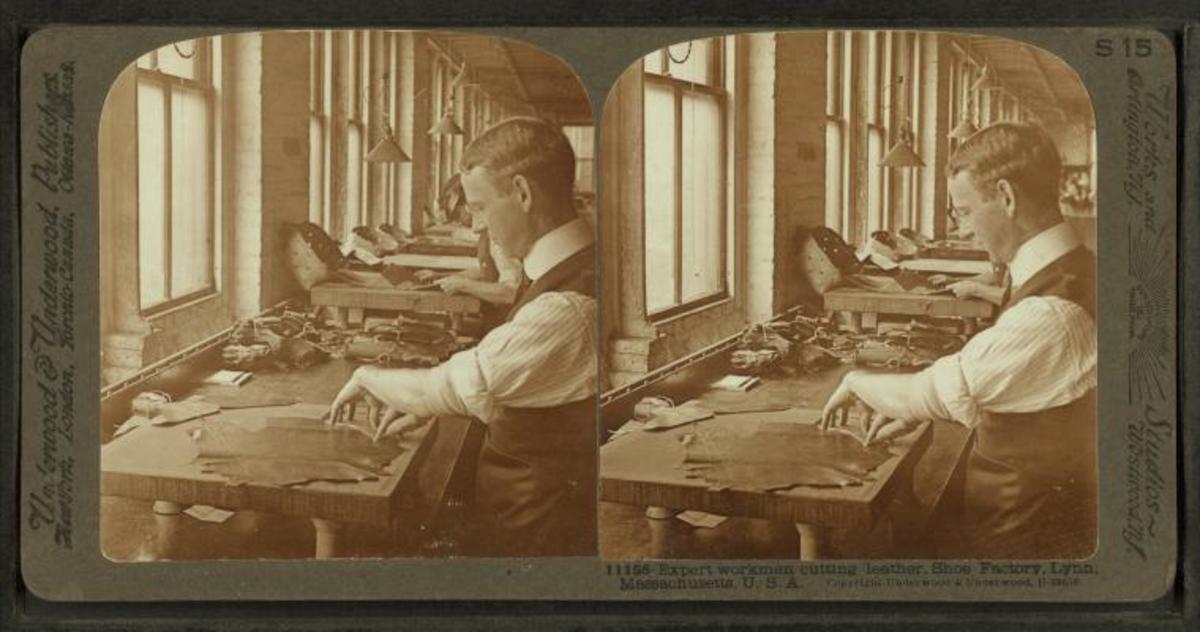

It is no surprise that many Southerners had a problem with the break-up of plantations, but they were not the only ones. Throughout the North there was a general resistance to blacks owning any land. Though the majority of Northerners supported the end of slavery, freeing blacks from slavery was not the same as making them equals. Making them landowners was a step towards admitting equality. Historically, few free African-Americans in the North owned land, and most were dependent on whites for jobs and resources. White businessmen were afraid to lose an entire level of inexpensive working class laborers.

White Southerners wanted blacks to become share-croppers -- renting and cultivating land, but returning their crops to the owner for less than true profit. Cotton was still the most profitable crop in the region, and most ex-slaves had experience with it, so that is what blacks were encouraged to grow. However, the repetitious production of cotton wore out the nutrients in the soil, so the land produced less cotton each year. Thus most share-croppers eventually became financially indebted to the landowner. Despite the Republicans attempts to institute "40 acres and a mule", there was enough push back in Congress that sharecropping won out. Opposition to the Freedman's Bureau was wide-spread. With no self-sustaining apparatus in place, the Bureau continued to assist blacks with Federal money only until 1869. The promise of "40 acres and a mule" was never fulfilled.

Share-cropping debt resulted in near absolute white political power over the black vote in the South. At the time, votes were not private. The land owner could threaten to evict the share-cropper if he didn't like their voting choices. When share-cropping became the reality, many freed slaves wound up voting Democratic. As laborers and share-croppers, blacks in the south remained at the bottom of the class hierarchy. Despite a professed desire by the Federal Government to facilitate change, Southern society continued to treat blacks much in the same way they had treated them since slavery had spread and become accepted in the culture.

Educational Concerns

Education was an opportunity for blacks to rise out of the lower class and became an even bigger concern once land was closed to them. In the antebellum South, legislation prevented education of African-Americans. Now those laws had been repealed by the 14th amendment.

In a report to the Senate, J.W. Alvord, the Superintendent of Schools for the Freedmen's Bureau wrote, "A general desire for education is everywhere manifested. In some instances, as in Halifax county, very good schools were found taught and paid for by the colored people themselves." Education was valued not only an escape from wage labor and share-cropping. It also allowed people to read the Bible and other works, and to be more active in their religious, political, and social communities. Education gave blacks pride.

Many Northern whites were indifferent to black education as it had existed for some time in more Northern regions. Abolitionists opened schools in the south and went there to teach, but Congress did little to support them or protect black rights to education. Poor whites saw education as the only advantage they had over blacks and were openly hostile to black education. However, the number of black children with the ability to read and write increased dramatically in the first ten years after the Civil War and continued to rise through the end of the 1800s.

The Toughest Road

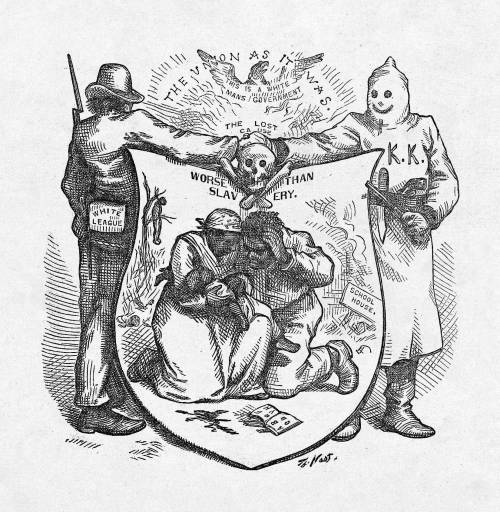

Despite distrust in the North, and legislation preventing former rebels from holding elected office, Southern Democrats soon became an influential force in Congress again. They allied with Northern Democrats to dissipate the tidal wave of Republican programs that constituted Reconstruction. Southern state legislatures were almost unanimously controlled by Democrats who, by proxy, held the power over the ex-slave vote. As long as blacks were not free to cast for whom they wanted, there was little hope of societal change.

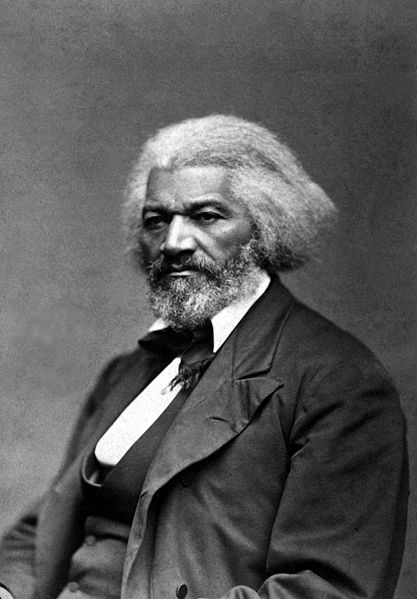

Fredrick Douglass, eminent African-American speaker, writer, abolitionist and ex-slave wrote that "by depriving us of suffrage...you declare before the world that we are unfit to exercise the elective franchise, and by this means lead us to undervalue ourselves...to feel like we have no possibilities like other men." The right to vote was a sign of respect before the world, much as the failure of European nations to support the Confederacy had been a sign of distaste for slavery. Douglass was also a champion of women's voting rights, education and right of employment for both sexes and all races. He opposed literacy tests as a voting requirement declaring, "if we know enough to be hung, we know enough to vote. If the Negro knows enough to pay taxes to support the government, he knows enough to vote; taxation and representation go together." The irony that this was the same argument made 100 years earlier when the American colonies were beginning to resent British taxes was lost on many in the South, but abolitionists eagerly flocked to support voting rights. Their successful lobbying resulted in the 15th amendment. The 15th amendment made it illegal to deny a citizen (at the time, male citizens) their right to vote based on race, creed, color and other reasons. It would be many years before there was a fair way to implement protection of these rights, but it was the first step towards freeing blacks to make their own political decisions.

Aftermath of Reconstruction

Reconstruction officially lasted until 1879. when all the rebellious states were considered "restored", but it's after effects linger to the present. Fredrick Douglass and the ex-slaves living there, and even blacks living in the North and West did not find the years after the Civil War a paradise. By comparison, today's world is a mecca of freedom. Nominally, schools are de-segregated and open to all, voting rights are enforced nationwide, any one can own property or apply for work. However, I suspect Fredrick Douglass would feel disappointment that 150 years after the Civil War racial tension and prejudice are still prevalent in the U.S. One has only to look at the events of Ferguson, MO in the summer of 2014 to see the lingering effects and resentment. The colors and creeds may have changed but the fear of "others" is still with us. Throughout history, groups move from place to place, cultures mingle and societies diversify. We can either embrace these changes and grow, or resist them and create centuries of bad blood and stigma that echo in ripples on the still pool of time.