- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Books & Novels»

- Nonfiction»

- Biographies & Memoirs

Short Biography of Cecil Rhodes

Cecil Rhodes was a man of his times. A British imperialist, Rhodes worked for the greatness of the British Empire. He was though, far more than just an imperialist; he was an explorer, an entrepreneur, a businessman, and a politician.

The passage of time since his death has ensured that Cecil Rhodes’ image and reputation has become tarnished, as of course has imperialism, but in his day he was considered a Great Briton.

Cecil Rhodes

The Childhood of Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes was born on July 5, 1853, in Bishops Stortford, Hertfordshire, England. Rhodes was the fifth of nine siblings born to the Reverend Francis William Rhodes and Louisa Peacock Rhodes. His early childhood was uneventful, and as befitted the son of a clergyman, Rhodes attended Bishop’s Stortford Grammar School.

It was whilst attending Bishop’s Stortford Grammar School that he was first taken ill. The local doctor diagnosed asthma linked to a tubercular lung condition.

The English climate is not an ideal one for those suffering with lung conditions, and during the 18th and 19th centuries it was not uncommon for doctor’s to advise a trip to a drier climate. This was what was advised for Cecil Rhodes.

One of Cecil’s brothers was in the army, but Cecil was not fit enough for that, and so it was to southern Africa and the Cape Colony that the Rhodes family decided to send Cecil.

Cecil Rhodes in Natal

In southern Africa, Cecil had an older brother, Herbert, who was farming on a cotton farm. Cecil was only 16 years of age when he arrived in South Africa in October 1870.

On arrival in South Africa, Cecil found that Herbert had given up on cotton farming, and had departed for the newly opened Kimberley diamond fields, with the aim of making a fortune for himself. Cecil though, was not worried about diamonds and threw himself into agriculture, opening the Rhodes Fruit Farms in the British colony.

Herbert had found little success with diamonds, although this did not stop him departing again in 1871 for another attempt. Again, Cecil stayed behind minding his fruit and cotton interests. Cecil though was faced with falling prices for his crops, and unable to support himself, he travelled to Kimberley in search of his brother.

The two Rhodes brothers staked a claim in the diamond fields, and Cecil sought out some financial backing to ensure that the stake wouldn’t fail. This money he found from the N.B. Rothschild and Sons Company. With money behind him, Cecil started speculating.

Rhodes saw that there were fortunes to be made in diamonds, but it wasn’t the only way. Cecil Rhodes had already established himself as somewhat of an entrepreneur with his Fruit Farms, and so Rhodes started providing services to the other miners, firstly water but then moving into mining equipment. With the profits from this business, Cecil would re-invest buying up land and other mines.

Two years in the Kimberley diamond fields saw Rhodes with a decent amount of savings, enough for him to return to England, to attend Oxford University and Oriel College to finish his schooling. Rhodes left his interests in the hands of one of his associates, Charles Rudd.

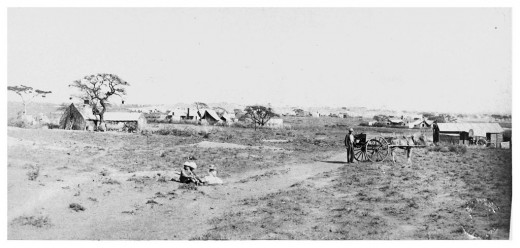

Kimberley Diamond Fields

Cecil Rhodes back in England

His studies at university were frequently interrupted by illness; his years in the cape colony had by no means cured him.

Rhodes completed one year at Oxford in 1873, and a second in 1876, but it wasn’t until 1881 that he finally completed his degree course. The periods in between, were spent back in southern Africa, looking after his interests and recovering his health.

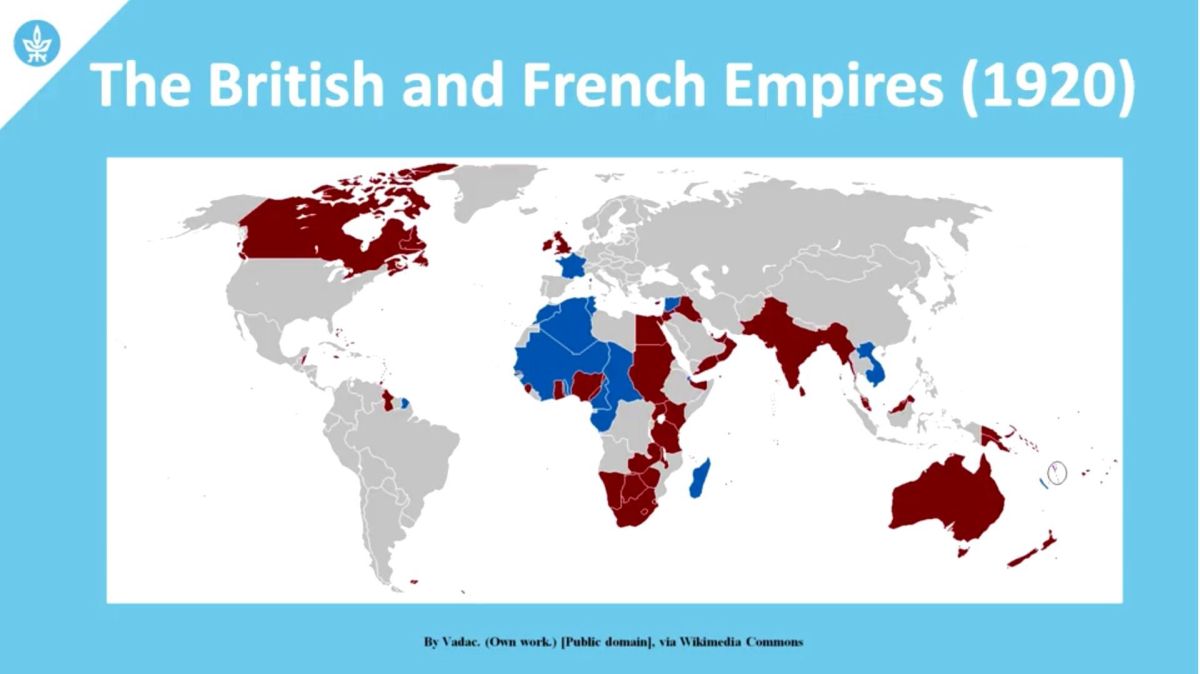

Oxford University was to have a big influence on Cecil, and his interest in British Imperialism was given new vigour. Rhodes would return to South Africa, after his studies had completed, with the strong view that the British Empire needed to grow. Travelling all over southern Africa, through the Transvaal and Bechuanaland, Rhodes dreamt of British control over all of the land.

Sketch of Cecil Rhodes

Back in Africa

Imperialism aside, Rhodes continued with his diamond operations. Rhodes, and Rudd on his behalf, continued to buy up mining rights. Often these purchases were brought for very little outlay, as the Kimberley fields were in a state of depression.

Soon, Rhodes found he had a monopoly within the diamond fields, he realised that care was needed though, or else the market could be flooded with diamonds, reducing their worth. In 1880, Rhodes formed the De Beers Mining Company with the intention of controlling the output of diamonds from the Kimberley diamond field.

Rhodes was well on his way to becoming one of the key individuals in South Africa. In 1881 Rhodes entered politics, obtaining a seat in the Cape Colony Parliament. He used his political connections to push his dream of British rule from Cairo to Cape Town.

Rhodes pushed through the British control of Bechuanaland in 1885, creating the Bechuanaland Protectorate. Rhodes was also adept at getting tribal chiefs to sign up with his company for mining rights. Once rights had been granted, he then sought British protection for his mines.

The most famous and controversial of these agreements with local chiefs was with Lobengula, King of the Ndebele of Matabeleland.

In 1888, Rhodes obtained mining concession to an area of land that later became Rhodesia. The signed agreement though, was not exactly what had been agreed in negotiations, but by then it was too late for Lobengula.

The British South Africa Company

With a large number of concessions under his belt, Rhodes created the British South Africa Company (BSAC). Rhodes saw this company as being a replacement for the British Colonial Office.

Rhodes hoped that further concessions and land could be gained; but whilst the BSAC managed to put white settlers into Matabeleland, it was stopped from expansion by the British government who decided to keep London’s control over British Central Africa (Nyasaland).

Rhodes was forced to settle for using the BSAC to develop Matabeleland and neighbouring Mashonaland. Settlers were brought into work in gold mines, although a relative lack of gold saw many become farmers instead. A rebellion by local tribes was suppressed, partially by force, and partially by the negotiation of Rhodes. The BSAC eventually ended up controlling over a million square kilometres of land and in 1895, the settlers changed the name of the country to Rhodesia in recognition of Cecil Rhodes.

Rise and Fall

Despite setbacks with the BSAC, Rhodes still did well in southern African politics. In 1890, Rhodes was elected Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, and he sought to make a combined South African Federation. Without the backing of the British Government, this would be but a dream. This dream though, would prove to be the end of Rhodes’ political career.

In 1895, Rhodes conspired to overthrow the Boer government of South Africa by force. Arming a band of British settlers, under the leadership of Leander Jameson, Rhodes anticipated a rising up of British settlers in South Africa. Unfortunately for Rhodes, no-one else joined the rebellion and Jameson was captured. Rhodes, whilst not arrested, was officially cautioned by the British Government and forced to resign from politics.

Resignation meant that he found himself with time to devote to the development of Rhodesia and the creation of his dream railway from Cairo to Cape Town. This dream failed to come to fruition, just as his dream of the British Empire running the same route had done.

The Boer War was soon to break out, and Rhodes returned to South Africa to assist. In October 1899, Rhodes was in the besieged Kimberley, staying there and commanding a section of troops, until the town was relieved in February 1900.

Despite political aspirations, Rhodes did not neglect his business interests, using politics for business gain, and business for political gain.

From Cape Town to Cairo

Cecil Rhodes

...and Rise Again

De Beers continued to grow, and in 1888, it joined with the interests of Barnie Barnato to become the De Beers Consolidated Mines, Ltd. Rhodes also formed the Consolidated Goldfields Company which oversaw gold production in South Africa. Rhodes managed to acquire monopolies in both fields. So great was his monopoly, that even into the middle of the twentieth century, De Beers still controlled 90% of all diamond production.

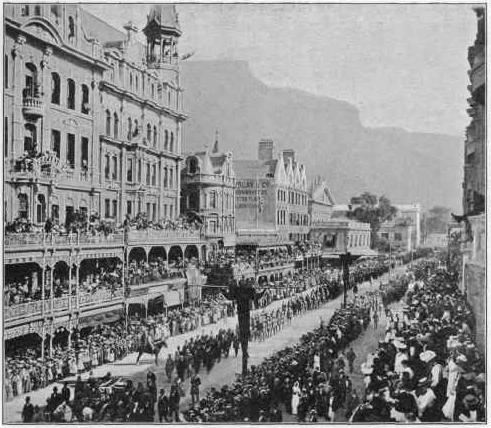

Funeral of Cecil Rhodes in Adderley St, Cape Town

Personal Life

There have been questions about Rhodes’ sexuality. He would often be found with male companionship and he never married. There is though no evidence that he ever had sex with any of his male companions, and it is best thought of as comradeship. Rhodes never married and there appears to have been few women in his life. The only one of real note was a Polish Princess called Catherine Radziwill, who claimed she was engaged to Rhodes shortly before his death, although these claims were later disproved.

Rhodes was never the strongest of men, health-wise. In addition to his childhood asthma and lung problems, he had suffered a heart attack at nineteen. A weak heart caused Rhodes to pass away on the March 26, 1902; he was only forty-nine years of age at the time. Dying at his Cape Town cottage, Rhodes was buried in Rhodesia, at Matopos Hills, south of Bulawayo.

Upon his death, Rhodes was thought to be one of the richest men in the world. De Beers continued to operate, although most of Rhodes’ wealth went to various projects around the world. Rhodes’ last will left a number of bequests, one of the main benefactors was the Rhodes Scholarships at Oxford. This scholarship stated that money would be given to students from Britain, the British Empire or Germany to allow them to study at Oxford.

Other notable bequests were in the form of land. Land on the slopes of Table Mountain was left to the people of South Africa, whilst similar land was also left in Rhodesia.In a recent poll, Cecil Rhodes was still voted amongst the 100 greatest South Africans.

Rhodes had left a number of wills throughout his life, the first of which had been made at nineteen when he had expressed a wish to create an organisation to bring the whole world under British control.

It is difficult to separate Rhodes from imperialism, though at the same time it must be remembered what an extraordinary businessman he was. Managing to create a monopoly with De Beers that even today accounts for 60 percent of worldwide diamond production is no mean achievement. History views him as a racist, often blamed for Apartheid and white rule, but he was purely a man of his times.

Cecil Rhodes Memorial Cape Town