- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era

Sickness and Health in eighteenth century Europe

The eighteenth century saw an improvement in health standards throughout Northern Europe as many traditional illnesses died out. The diet of the individual was improving as better agricultural techniques resulted in a more plentiful food supply and a higher intake of protein for the average person.

Malaria

One of the major illnesses to be eradicated at this time was malaria. Most modern Europeans think of malaria as an exotic disease which is caught in Asia if you do not take the appropriate medication. Prior to the Industrial Revolution there were epidemics of malaria within Northern Europe. It was the planting and cultivation of turnips which reduced the number of outbreaks. An increased supply of turnips led to larger cattle herds as there was more for them to eat. The malaria bearing mosquitoes were attracted to the cows as they had a larger supply of blood. Cows are immune to malaria and do not transmit it, so the chain of infection ended. Malaria was at this point confined to the mediterranean where low rainfall in the summer meant less fodder was grown and less cows grazed.

Better Home Standards

Animals had traditionally been kept in the home, but rising living standards allowed for the erection of separate quarters for the animals which led to a fall in diseases transmitted from animals to man , such as tuberculosis and brucellosis.

Medical Treatments

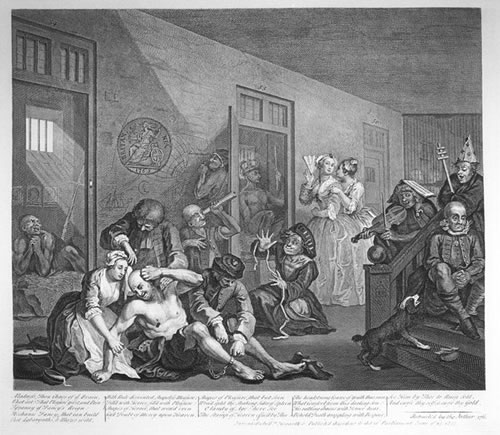

Medical research was limited and physicians had little idea as to what caused illness. They believed that any symptoms were symptoms of bodily disorders which could be treated by change of diet, bleeding, purging or sweating. Bleeding with leeches was a common treatment which often killed a patient who was already weakened by disease. Often in outbreaks of contagious disease the only treatment was isolation and quarantine which stopped it spreading.

Hospitals were a source of infection- with limited care and scant regard to hygiene. Ventilation was often poor and hospitals were often overcrowded. Food could be low quality and prepared in unhygienic conditions. Doctors often made snap diagnoses and had little scientific aids to help- the stethoscope and thermometer were not invented until the nineteenth century.

Training of doctors was poor, trainee doctors obtained an apprenticeship with a doctor and learnt from him. Until 1832 there were few corpses available for the surgeons to practise their operations. There were no anaesthetics so the most popular surgeons were the quickest ones! There was no antiseptics until the end of the next century so many died of infection in their wounds. The poor often looked after themselves using traditional herbal poultices the recipes handed down through the generations.

Smallpox

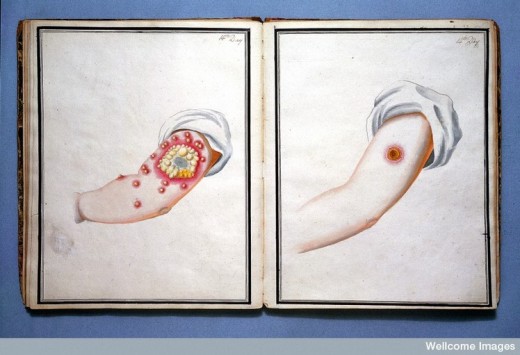

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, the wife of the British ambassador for Constantinople told society at large how the Turks had developed an inoculation against smallpox. The procedure involved making a scratch between the thumb and forefinger and putting a small quantity of small pox under the skin; by giving them a small dose they developed immunity to the full disease. This caused a stir in London and a trial was made on six men who had been sentenced to death. All the men survived the inoculation which prompted the King to inoculate the royal children in 1722. The inoculations were received well in the countryside but not so well in the cities where small pox was just another disease. Crowned heads of Europe including Catherine the Great of Russia and Frederick II of Prussia were inoculated, Louis xv of France did not have the inoculation and died of smallpox.

In 1798 Edward Jenner, a quiet English country doctor published his experiments. He found a safer procedure by inoculating patients with cowpox. This new inoculation was practised worldwide before the next century was a decade old

It was not until the nineteenth century that reforms in healthcare and legislation involving public health had an effect in further improvements in public health