The Myth of Race and the Curse of Racism

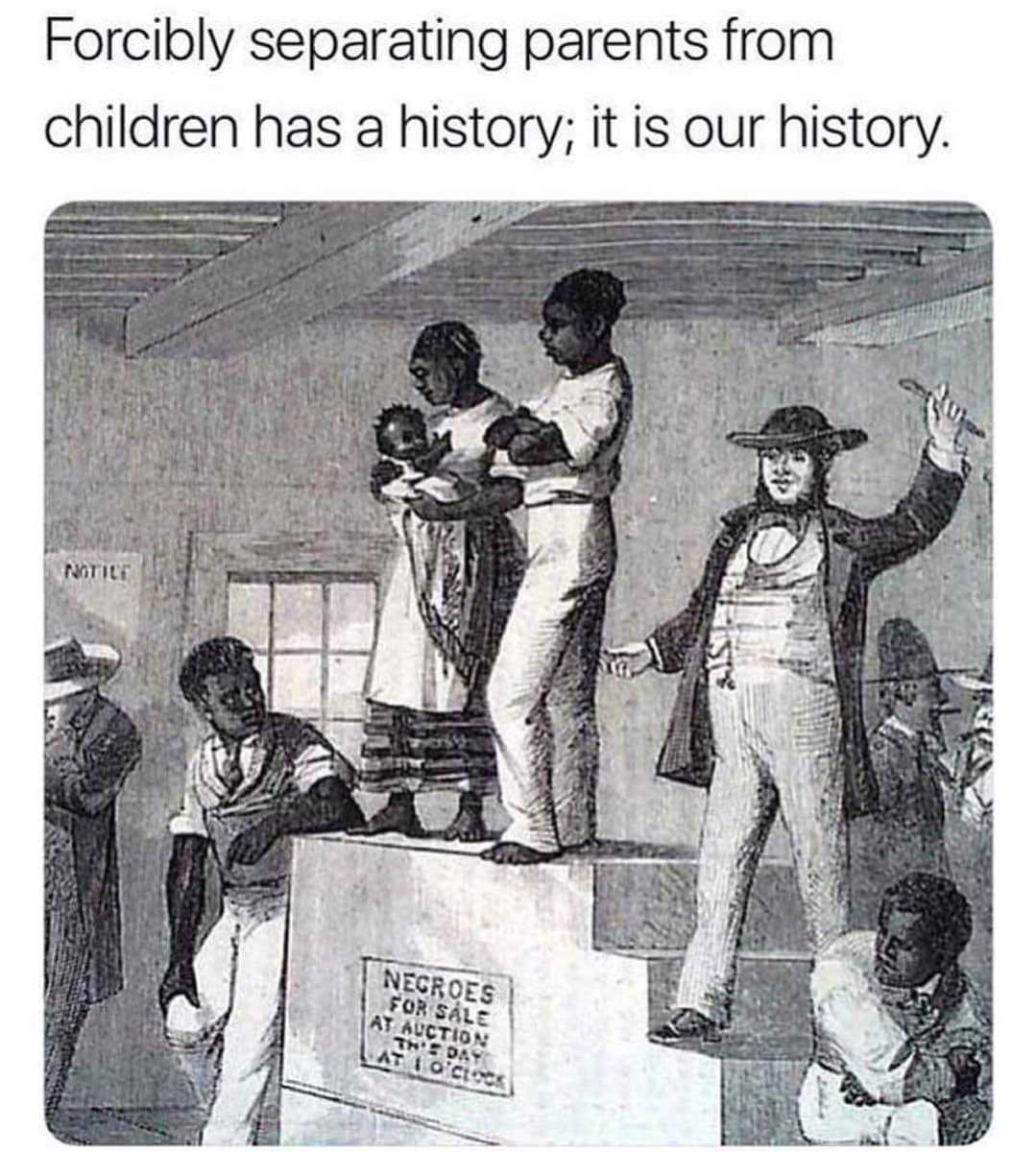

A Song About Lynchings

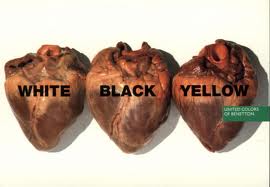

There is no scientific basis for the concept of race. Some would say this is a statement of opinion. In my view, it is an indisputable fact. The prevalence of a belief in the biological reality of race is one more piece of evidence confirming that the human race is not particularly rational. But as events in recent decades have shown, the human race may not be entirely hopeless.

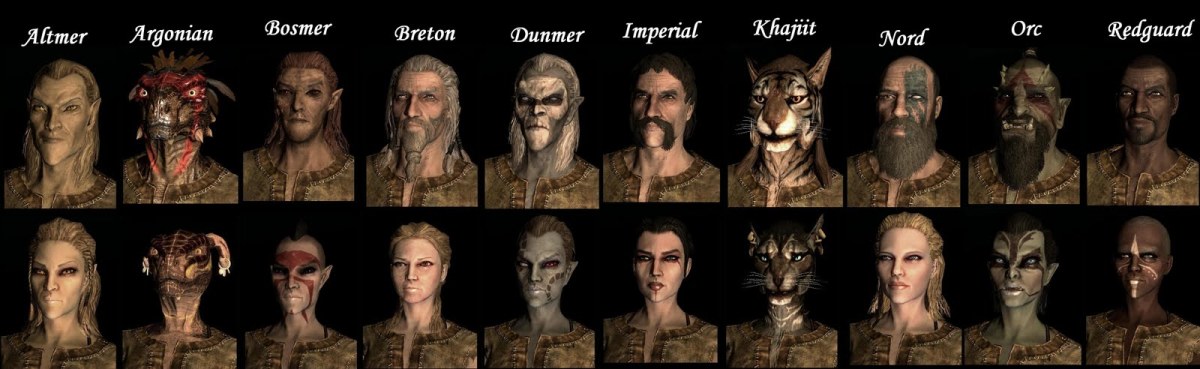

Every technique for racially classifying human beings is unavoidably arbitrary. Take physical appearance for instance. Skin tone is probably the most common method for classifying people. Some classification systems emphasize the shape of eyes, noses, or the texture of hair. But if you are going to use physical characteristics to classify people, it makes just as much sense to break people up on the basis of height, weight, hand size, quantity of body hair, length of ear lobes, or the shape of belly buttons. It is also important to remember that physical appearance can fluctuate. If a person of light skin tone hangs out too long at the beach or in a tanning salon, have they suddenly changed their racial identity? If people get nose jobs or have their hair straightened or curled, has their ethnicity changed?

Of course, racial distinctions are based on more than simply physical appearance. People committed to the biological reality of race emphasize ancestry as the determinant of racial identity. Following this logic, people are classified according to the geographic locations where their ancestors originated. There are two basic problems with this system. First, you have to make an arbitrary decision determining how many generations back you will trace an individual’s ancestry. To be considered a “pure blood” member of a so-called race, did all of your ancestors for three, five, ten, or twenty generations back have to come from a certain region? And to make things even more complicated, you have to trace the heritage of each of those ancestors in order to determine how “pure” their blood was. For practical purposes, people will typically go back only two or three generations in order to determine racial identity. Most of the time, we have limited information about more distant ancestors anyway. Tracing the ancestry of a grandparent or great-grandparent can really be a bitch. Plus, after more than a couple of generations, it would become clear that all of us are racial “mutts.” By any system of classification, it is hard to argue that anyone’s blood is remotely “pure.”

The other problem with tracing ancestry is geographic. It is impossible to draw clear boundaries between the areas inhabited by different (so-called) races. Where exactly, for instance, are the geographical boundaries of Europe? At what specific geographical location do the inhabitants cease to be “white”? Are people from Turkey, Kazakhstan, Bulgaria, Russia, and Morocco white, or are they members of some other racial group? A white supremacist, anthropologist, and geneticist might give different answers to this question. Then, if you take into account the fact that people have constantly been on the move throughout history, it is difficult to determine where any group actually comes from. If you go back far enough, all human beings are apparently immigrants from East Africa. Among certain groups devoted to notions of racial superiority, however, it would not go over very well if you told them that they were African.

But in spite of these obvious problems with the concept of race, we humans continue to place humans into arbitrary racial categories. So even though there are no significant biological distinctions between humans, race as a cultural concept is still important, and comparing the experiences of different culturally defined racial groups is still a worthwhile activity. Perception is more important than reality, and some philosophers would argue that perception is reality. Unfortunately, it is still naïve to believe that the United States, or anywhere else, is a colorblind society in which racial distinctions and discrimination are no longer significant. We still identify ourselves as members of different cultural and ethnic factions, and we all, even if on a subconscious level, are influenced by racial stereotypes.

It may be biological to latch onto a group and place others into categories. Given the harsh, competitive world in which our species evolved, it was important throughout history to know the difference between friends and enemies. We also live in cultures still impacted by the actions and racial attitudes of our ancestors. It is therefore easy to make excuses and to assume that some things will never change. We are all products of our upbringing, and racism, to a certain degree, may be ingrained into our DNA. A sense of defeatism, however, is not very helpful. Yes, we may be irrational creatures in many ways, guided more by primal fears and instinct than logic. This does not mean, however, that we should give up on doing our best to behave and think in ways that make sense. American history has proven that ancient racial attitudes can change, that progress is possible. Many people in my country and in the world have recognized the irrationality of racial prejudice and of the very concept of race itself. Hopefully, there will come a day when all of us are able to step back, recognize the existence and the foolishness of our prejudices, and work to stamp out the curse of racism once and for all.