The New Yorker who contributed to the rise of Afrikaner Nationalism

A minor disturbance

On an October day in 1815 a South African farmer was shot and killed while resisting arrest on his farm in the Eastern Cape Province. He had been summonsed several times over the previous two years to appear in court on charges of mistreating a Khoikhoi servant, and had consistently failed to do so.

What followed was an episode in which a displaced New Yorker named Jacob Glen Cuyler played a minor but nevertheless significant role, an episode which would, some years later, be used to stoke the often violent fires of Afrikaner nationalism, a movement which would culminate in the establishment of the apartheid state almost 150 years later.

The incident, while deemed insignificant at the time, a minor disturbance by some disgruntled frontiersmen, entered into the mythology of Afrikaner nationalism as evidence of British perfidy and the dangers posed by equality before the law of people of colour, providing for some people a contribution to the intellectual underpinning of and justification for the ideology of apartheid.

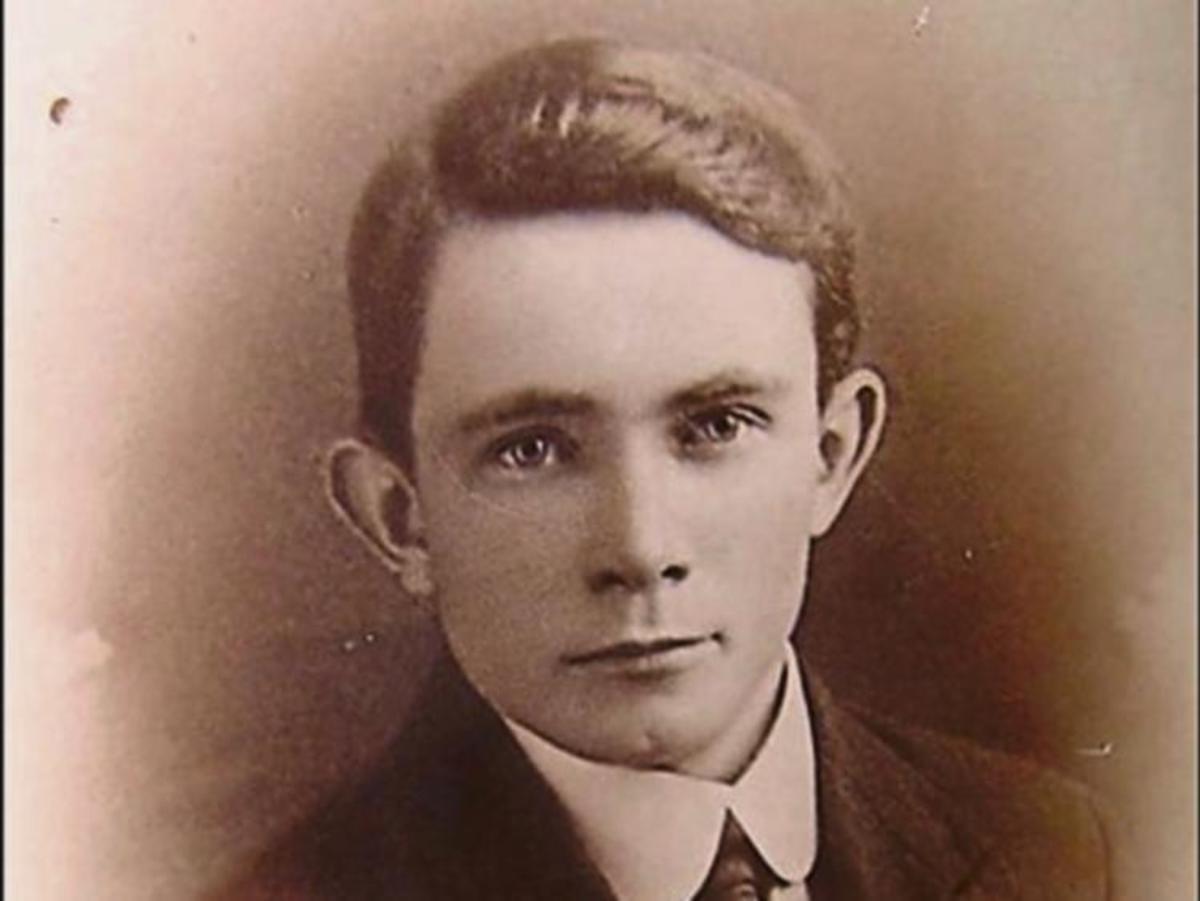

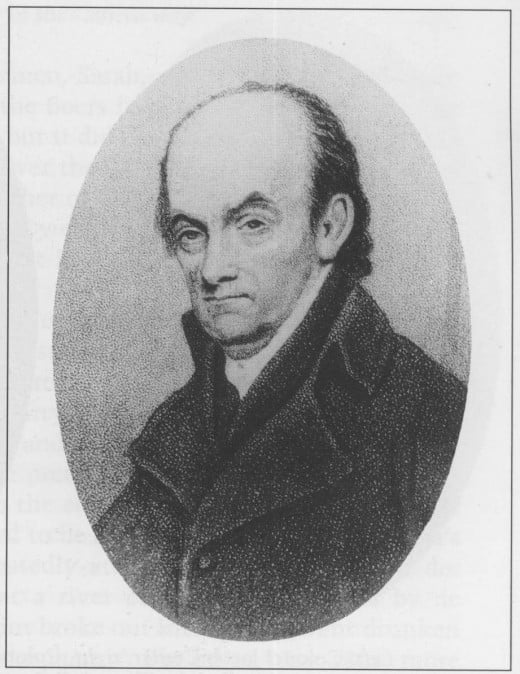

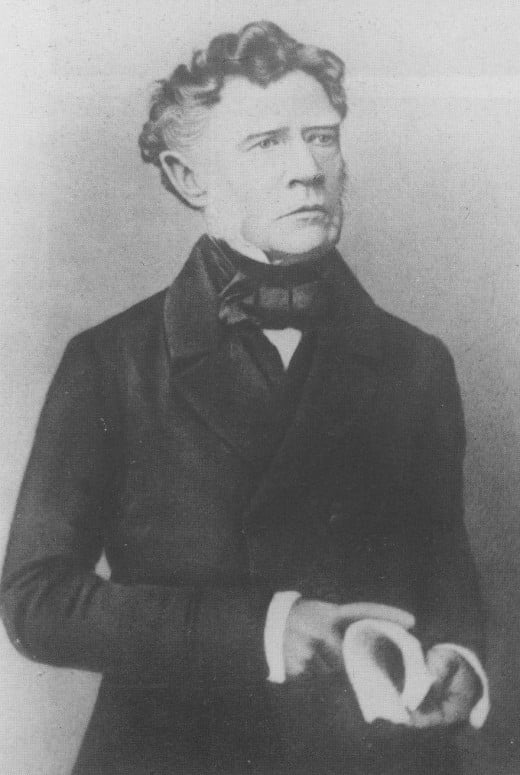

Jacob Glen Cuyler

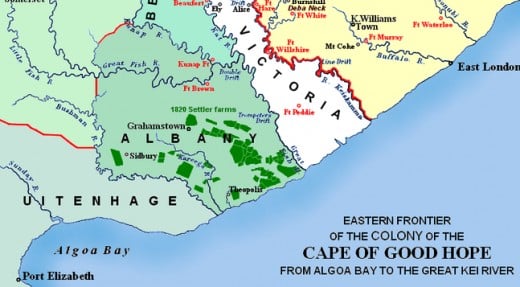

Jacob Glen Cuyler was born in August 1775 in Albany, New York, as community of which his father, Abraham C. Cuyler was the last colonial mayor, the third Cuyler to hold that position.

Abraham Cuyler was fiercely loyal to the British monarchy and the colonial government and as a result he lost everything in the revolution which brought about the independence of the United States in 1776.

He was condemned to death in 1779 under the Act of Attainder but managed to escape with his family to Canada, where he helped establish the town of Yorkfield, where he died in 1810.

Jacob Cuyler was born in 1775 in Albany and when the family moved to Canada he, as soon as he was of age, joined the British Army. In 1805 he was sent to the Cape Colony as part of the British forces of occupation which took over the colony from the Dutch.

The following year he was sent to the frontier as Landdrost (Magistrate) of the new town of Uitenhage near Algoa Bay. He was a man described by Noël Mostert in his magisterial history Frontiers (Pimlico, 1993) as “...a man devoid of any Enlightenment-inspired sentiment and idealism, who reacted with arrogant displeasure and vindictive fury to anyone who dared to oppose his will and commands.”

The officer in charge of the British occupying forces at the Cape, Sir David Baird, had specified that the person to be set in charge of frontier affairs should be someone “in whose judgement, discretion, knowledge of the Dutch language and conciliatory temper, a just reliance can be placed.”

As Mostert notes rather drily, “Measured against Baird's requirements, Jacob Cuyler was a poor choice.” Perhaps it was his knowledge of the Dutch language which outweighed all his disadvantages for the post.

Cuyler himself noted in a letter to his family, “I am convinced Sir David took me to possess a moderate temper.”

A cauldron of cultures

Cuyler came into an area where conflicts and disagreements were rife, where the cauldron of cultures was bubbling with antagonisms and mutual lack of understanding. A place where sensitivity, tact and firmness would serve rather better than hot-headedness and arrogance, the attributes Cuyler seemed to possess in abundance.

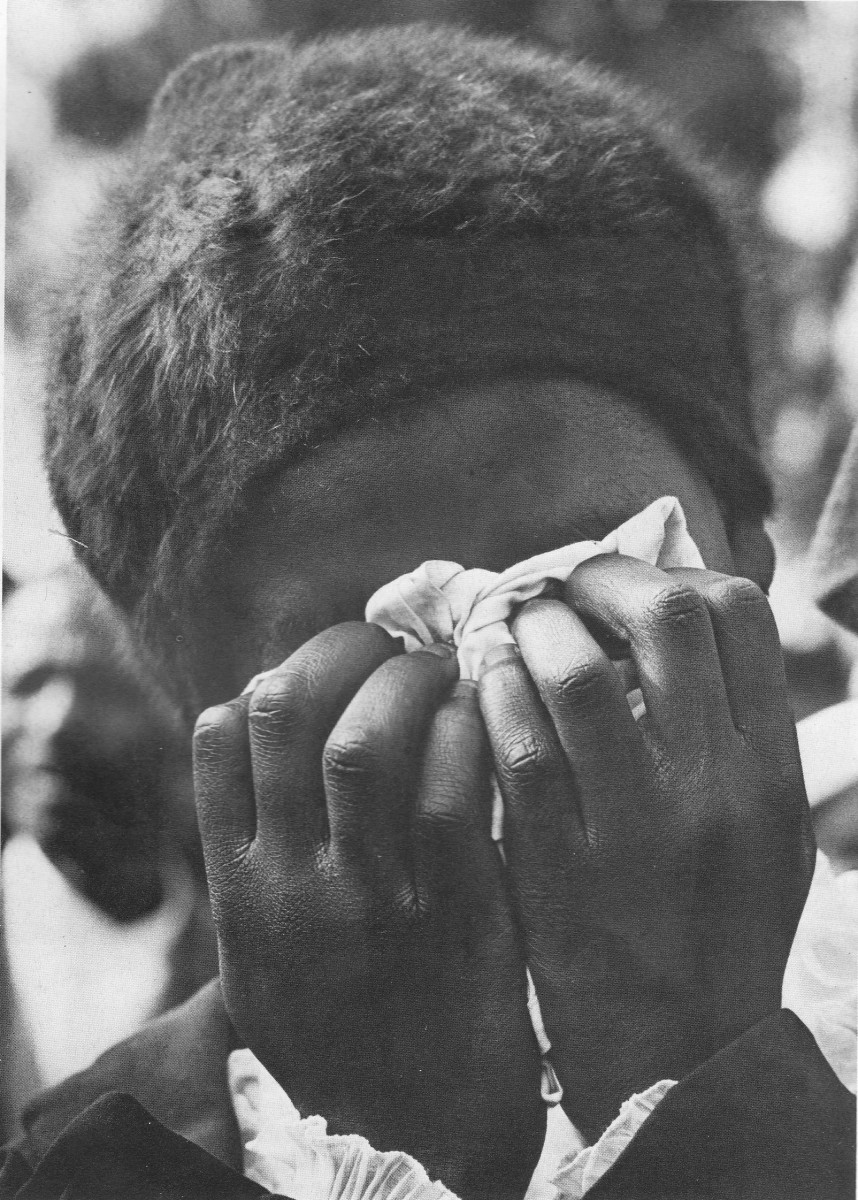

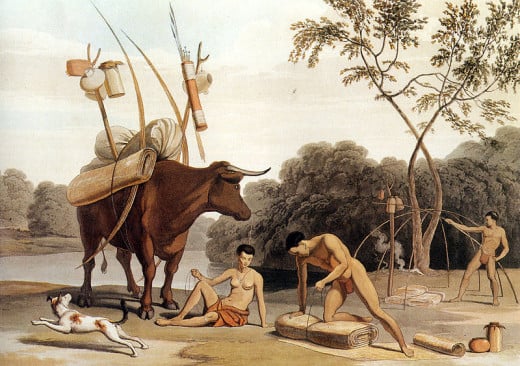

The cultures bubbling in the cauldron were a complex of Khoikhoi (also called Hottentots at the time) who were the aboriginal inhabitants of the area, the amaXhosa who were somewhat later arrivals in the area, the Dutch “trek boers” or farmers who moved from place to place in search of grazing for their herds, and the last arrivals, the British colonial government which had to maintain some sort of order.

Also looming large was the influence of the missionaries of the London Missionary Society (LMS) who were imbued with Christian fervour and enthusiasm ignited by the very “Enlightenment-inspired sentiment and idealism” which Mostert described Cuyler as totally lacking.

Moreover, these missionaries, in the main led by Johannes Theodosius van der Kemp and James Read Snr., had powerful connections back in Britain, connections which included the leader of the Abolitionist movement William Wilberforce. These missionaries were convinced, not without reason, that the Dutch farmers were chronically mistreating the Khoikhoi they employed, often in conditions approaching slavery.

The scene was set for some dramatic encounters.

The Spark

Into this tinder-box a spark was introduced by a Khoikhoi servant by the name of Booy (sometimes written as “Booi”) in the employ of a Dutch farmer called Frederick Cornelius Bezuidenhout, who complained in 1813 of mistreatment by his master.

The complaint was laid to the Landdrost of Graaf Reinet, Andries (later Sir Andries) Stockenström , a cultured and refined man who took his work very seriously. Bezuidenhout refused go to Graaf Reinet to answer to the charges. Stockenstrom was not amused.

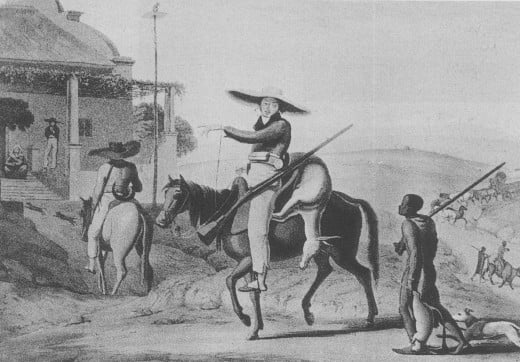

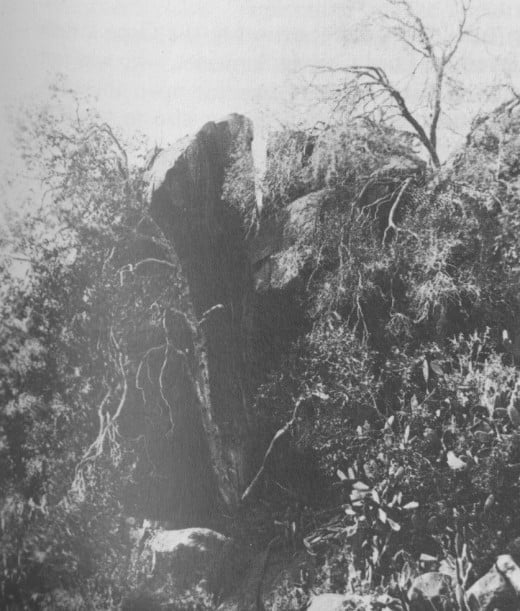

In October 1815 Bezuidenhout was sentenced in absentia to one month in gaol and Stockenstrom sent a small force of 12 Khoikhoi soldiers under a white officer to arrest Bezuidenhout. They arrived at his farm on 16 October and the boer holed up in a rocky outcrop on the farm from which he began firing, with the help of his mixed-blood wife and his servants, on the troops, who returned his fire.

Bezuidenhout shouted at the troops: “What does Stockenström think? I care for my life just as much as nothing.”

By the end of the day Bezuidenhout was dead, and the myth-making began.

High treason

Bezuidenhout was buried on his farm and at the funeral his brother, Johannes, swore to avenge Frederck's death.

Along with another fiery-tempered boer, Hendrik Prinsloo, Johannes Bezuidenhout began to try to get support for a rebellion against the British authorities from his fellow Dutch farmers in the area. He did not get much and so he even tried to get the amaXhosa of Ngqika, the chief just across the Fish River boundary of the Colony, to assist in driving the British out. Ngqika, being a very clever strategist and having excellent information, was non-committal and eventually unenthusiastic.

A motley assembly of boers was eventually attacked by Cuyler and some 60 of them surrendered to the British troops without a shot being fired. Bezuidenhout and three of the other leaders of the putative rebellion attempted to escape into the territory of the amaXhosa but were captured and brought back to face trial. In the fight Bezuidenhout was killed.

Five of the other ringleaders, including Henrik Prinsloo, were sentenced to death in January 1816 after being found guilty of high treason.

The sentencing of the five started the climax of the myth.

"God-forgotten, tyrants and villains.”

The five were taken to a ridge called Slagter's Nek (sometimes written “Slachter's Nek”) or “Butcher's Ridge (or perhaps more accurately 'col')” on 9 March 1816 where Cuyler and Stockenstrom would oversee their execution.

A large crowd of people from the area affected by the rebellion were forced to watch the execution, including Bezuidenhout's wife while one of the leaders was tied to the gallows by his neck. The execution was guarded by 300 troops while the two Landdrosts sat regally on their horses to watch.

The condemned men were assisted to prepare for their execution by the local minister Dominee (Reverend) T.J. Herold of the Uitenhage Dutch Reformed Church congregation. They sang a hymn, joined by many of their compatriots around the sorry scene and then the platform was dropped.

Four of the ropes snapped while one did its grisly work. There followed a frantic search for more rope, while the friends of the remaining condemned men pleaded with Cuyler to stay their execution, but he refused, claiming, probably correctly, he did not have the authority to do so.

So in the shadow of the gallows, from which the corpse of their colleague still hung, the four awaited the arrival of replacement ropes which came several hours later and the executions were completed.

Cuyler later wrote: “I cannot describe the distressed countenances of the inhabitants at this moment who were sentenced to witness the execution.”

The myth, the apartheid-sustaining legend, that arose from this sad incident, was an elaboration of the fact that the Bezuidenhouts and the other would-be rebels had been caught by Khoikhoi soldiers and judged by representatives of the British, the “God-forgotten, tyrants and villains.”

The legacy - from minor disturbance to foundational myth

As Mostert notes, the Slagter's Nek Rebellion "records the emergence of a new white social class in South Africa. The rebels were indeed mostly poor and landless men."

He continues, "The 'poor whites', within a different national and social context, ultimately were to become the principle constituency for a twentieth-century Afrikaner nationalism that took its first symbols from Slagter's Nek."

Afrikaner historian Professor F.A. (Floors) van Jaarsveld (who in 1979 would be tarred and feathered by the extreme right wing Afrikaner Weerstands Beweging of the murdered Eugene Terre'Blanche for daring to demythologise the "sacred" Day of the Covenant which commemorated the defeat of the amaZulu by the Boers at the Battle of Blood River in 1838 at a public meeting) wrote in his seminal book The Afrikaner's Interpretation of South African History (Simondium, 1964):

It was approximately in 1868 only when ... Slagter's Nek was 'discovered' ... to symbolise the way in which the British treated the Afrikaners. Anyone wishing to arouse feelings had merely to hark back to the Slagter's Nek affair ... by 1899 it was seen as 'bloody murder' ... The unfortunate men of Slagter's Nek had been transformed into 'martyrs' for Afrikaner freedom and victims of 'British cruelty'.

Cuyler ensured his part in this sad episode would be remembered by naming the area in which it had taken place "Albany" after his birthplace, a name by which it is still known today.