Early Roman Wars

The era of the early Roman wars is a very interesting topic. And this is probably the one period in Roman history that you've never learnt much about. You've never read a book or magazine article about how Rome came to be. You've never seen a film about it, because everyone seems to be so fascinated by the emperors and their dealings that no one has time for Romulus and the wolf that nurtured him. Well, me neither. Because Romulus is fiction. But here follows a grain of the truth instead, and the what's and whys and hows of early Roman history.

I. The Regal Period

Environs

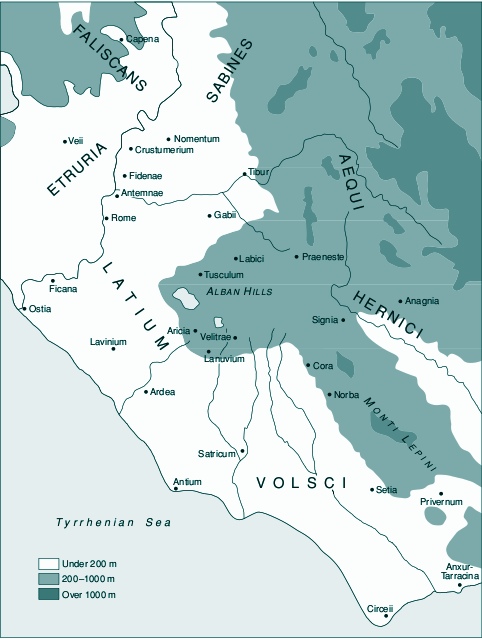

In the beginning Rome was no more than one of many communities of Latins that inhabited the plain south of the Tiber and the surrounding hillsides, shared the same material culture and spoke the same Indo-European dialect.

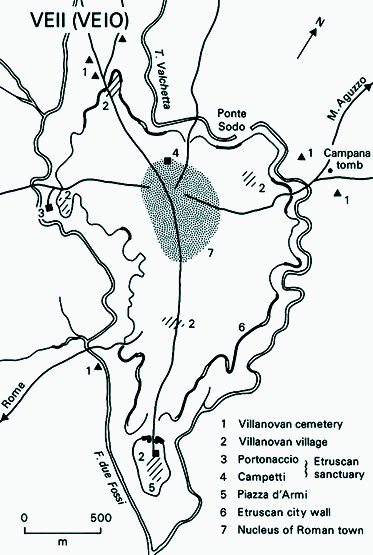

North of the Tiber dwelt the Etruscans who were non-Indo-European speakers. Rome's closest Etruscan neighbor was Veii having much in common with the Latins.

Still north of the river but east of Veii dwelt the Faliscans. Other linguistically related peoples such as the Sabines lived further up beyond the Latins on the Roman side of the river.

Further away to the east lived the Aequi, the Volsci and the Hernici, all of which peoples took their fair share in early Roman history. It is this wild range of peoples competing for the same lands that played a crucial role in the early development of Rome.

Habitation

Several hut-villages were formed on the Palatine Hill as early as around 1000 BC. Archeological finds show some spectacular wealth from the eighth century as well as remarkable social stratification. The first appearance of public buildings in Rome can be dated back to as early as the seventh century by which time the former village community had evolved into a city-state.

From this time through the sixth century Rome was ruled by at least seven kings in an era of enhanced prosperity with the city-state being the most flourishing place in Latium.

By the end of the sixth century the city also expanded its territory with a significant bridgehead on the right bank and lands reaching out as far as the seashores on the left bank of the river. In the south Roman territory extended up to the foothills of the Alban Mount. All this land measured up to 822 square kilometers, which is over the third of all Latin territory.

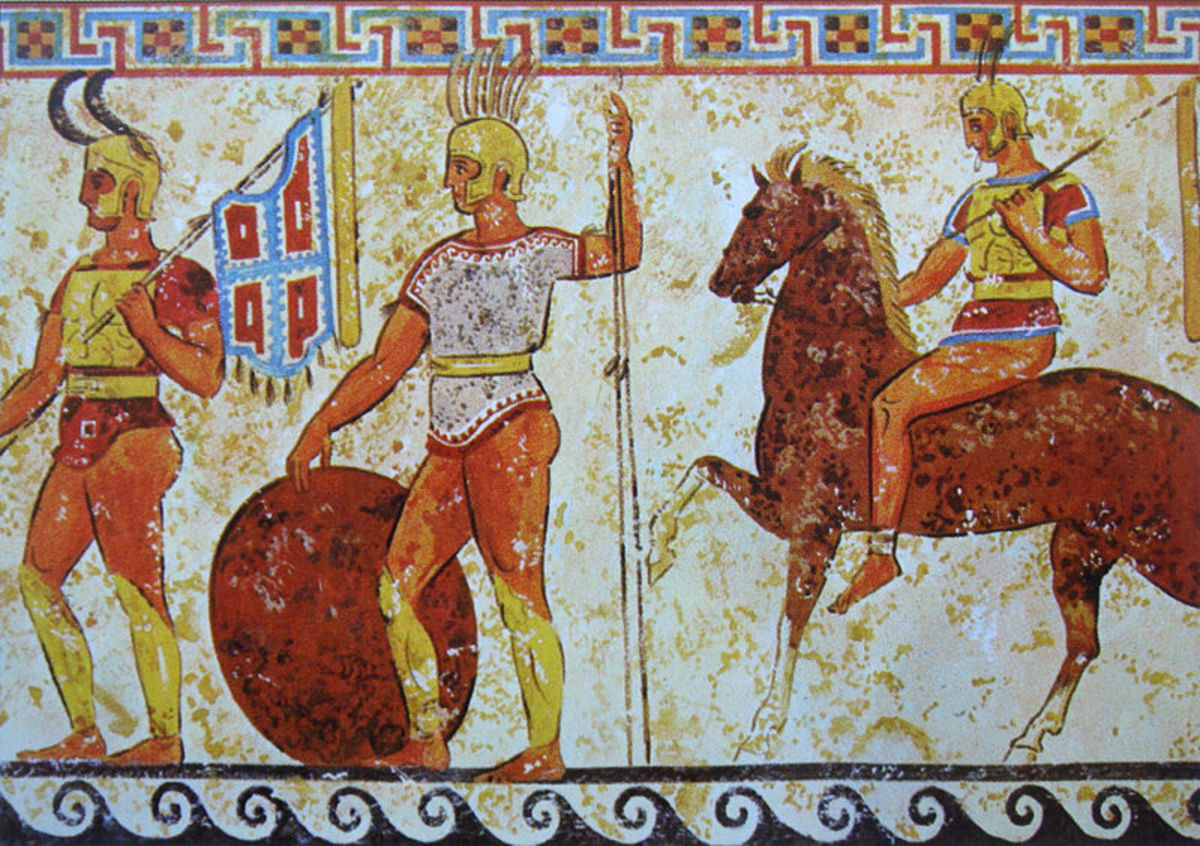

Warfare

Although, wars were not the only means by which Romans were able to extend their power, they were more often at war with their neighbors than not, because these wars were the sources of wealth unmeasurable. Legend has it that the great temple on the Capitol was raised from the spoils of the last Tarquin's capture of Pometia.

War, actually, was not only common, but a regular annual occurrence. Ancient rituals were held in March and in October in honour of the opening and closing of the campaign season.

We have clear evidence that war was rampant in archaic Latium. The first earth ramparts with ditches and other fortifications appear in the early eighth century. The most significant site of such a complex defence system is the approach to Ardea where three successive protective ramparts were built.

One town, Lavinium, even had acquired a stone circuit wall by as early as the sixth century. Stone fortifications around Etruscan cities followed this example in the late fifth century and Rome legging way behind built its own stone circuit wall, the Servian Wall, in the early fourth century.

II. The Early Republic

Preeminence among Latins

In 509 the king was banished for uncertain reasons and replaced by two chief magistrates called praetors who were elected annually. In the years of the early republic the Romans were almost constantly at war, but in the fifth century they were mostly on the defensive against enemy attacks often fighting for survival.

The expulsion of the kings ushered in a phase of widespread turbulence in the Tiber region, besides other conflicts the city-state was confronted by a coalition of Latin communities and was even occupied for a while by the Etruscan warlord, Lars Porsenna. However this time of insecurity was cut short when the Romans defeated the Latins in a decisive battle at Lake Regillus in 499 and took over Fidenae and Crustumerium upstream on the Tiber left bank.

Treaties of alliance were signed with the Latins and the Hernici living in the upper vale of the Sacco, cut off from the Tiber Valley by the watershed between Praeneste and the Alban Hills. Legend has it that the same Roman general, Spurius Cassius, negotiated both of these treaties. The pledge of allegiance brought about a new epoch of peace among the Latins and there was little wavering in their loyalty towards Rome until 389.

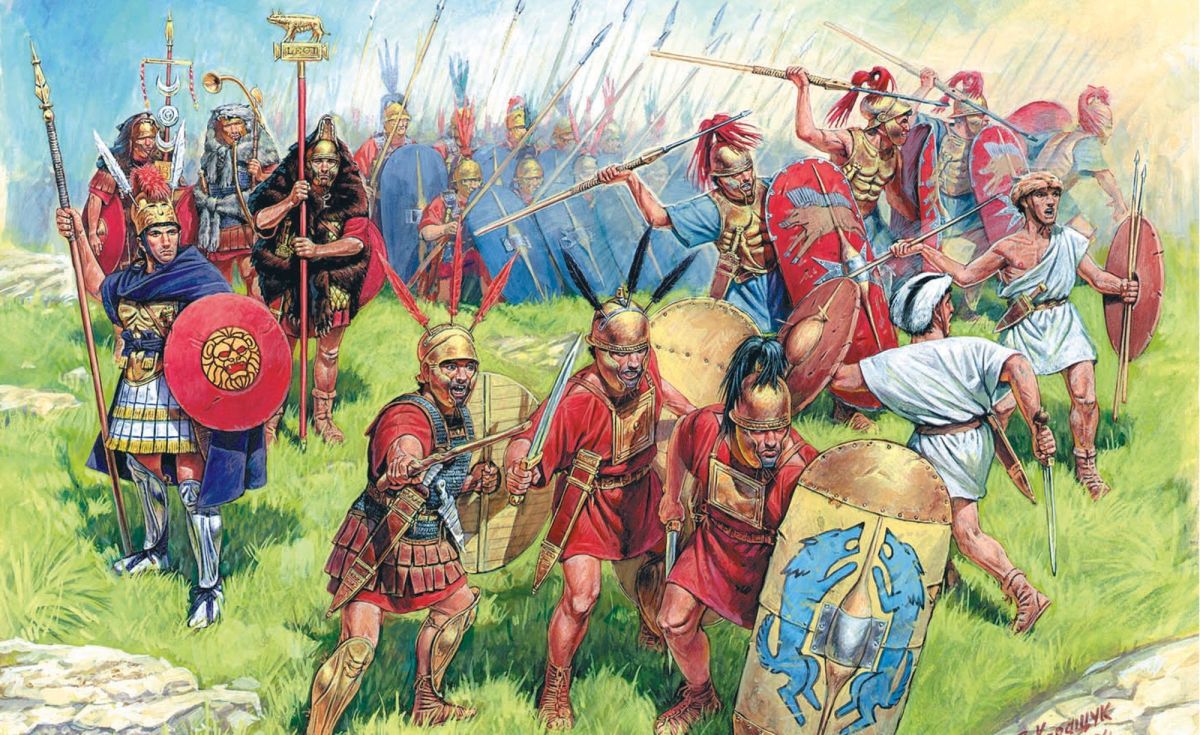

Wars with non-Latins

While there was peace amongst the Latin city-states there were frequent conflicts with such peoples as the Sabines, the Volsci and the Aequi. Often the enemy rode on Roman territory marauding the villages with the Romans suffering reverses, but even more often this happened to the allies of Rome as their lands were much closer to these hostile city-states. The enemy was tough and the only means by which Rome could take vengeance was contenting themselves with retaliatory plundering.

From earlier times the Romans knew the Sabines of the Tiber Valley as turncoats. They often appeared with peaceful and seemingly friendly intent that turned out to be a cunning form of violent take-over in the end. The wars with the Aequi and the Volsci, however, were due to the regional turbulences in the fifth century and the resulting alliance with the Latins and The Hernici, which posed a threat to these peoples. The Romans were in a more or less comfortable position, because they were separated from the Aequian and Volscian lands by other Latin communities. While getting forced into submission by Rome, another reason for these Latin states to accept the Roman alliance offers in 493 and 486 was the prospect of help against the new enemies.

The Volsci lived in the coastal Pomptine plain from Antium to Anxur and the adjacent Monti Lepini and were mainly invaders from the central Italian mountains in origin. Now many dwelt on the coast or in the plain raising settlements of urban character.

The Aequi lived in the upper Aniene Vale and the mountains that engulf it. They had easy passage into the Sacco Valley from there. However, the farthest they could go during these wars was laying siege to Algidus, but unreliable historical tradition may suggest otherwise.

Due to the nature of these conflicts, the Romans did well out of the Aequian and Volscian wars. Very seldom was there any fighting on Roman territory and the chief involvement of the city-state was in dispatching armies to support their Latin and Hernican allies. At the turn of the fifth and fourth centuries the Romans advanced deep into the Volsci territory and also temporarily took control over Tarracina, their name for Anxur, and founded a colony at Circeii.

- Fordham University of New York

Internet History Sourcebooks Project at fordham.edu. Extensive selection of useful links. - First Europe Tutorial - Roman Territorial Expansion

Expansion during the Early Roman Republic (509 - 265 B.C.E.) - The Roman Army

Nowhere does the Roman talent for organization show itself so clearly as in its army. The story of the Roman army is an extensive one, demonstrated in part by the scale of this chapter. - Would you like to live in Ancient Rome?

I wrote this hub as a sequel to 'Are you who you were five years ago?'. However, it is easy to understand on its own, because it deals with another subject within the concept of individual and social values....

Wars with Veii

After great victories against the Aequi and Volsci in the late fifth century, which left Rome at the peak of its strength in the period of the early republic, a new phase of expansion began. Three consequent wars with the Etruscan city-state of Veii were fought. The first war was started by Rome, the second began when Fidenae revolted against Rome to Veii and these were mostly local uprisings of neighboring communities. The third war, however, saw terrible bloodshed and was a fight to the death. In 396, Camillius laid siege to Veii and in bloody battle captured it. Some inhabitants were raised to the rank of Roman citizen, but most were sold into slavery. The land taken from Veii became public property (ager publicus) and afterwards was distributed to Roman citizens in small allotments. This portion of land was huge and extended the Roman territory to about 1500 square kilometers in all.

In subsequent campaigns the Romans strengthened their hold north of the Tiber and exalted submission from Faliscan communities such as Capena and Falerii.

In 387, however, the Roman advance was halted by a horde of invading Gauls who crushed a significant Roman army near Crustumerium at the River Allia. The Gauls didn't raze the city, but sacked it and then departed. To insure against another such incident a circuit wall was constructed engulfing an area of 430 hectares around the city.

There were further wars in southern Etruria that ended with the establishment of colonies at Satrium and Nepet. The Aequi attacked but for the last time, a meagre effort from their part. The Volsci kept harassing the Latins for some more time, but by the mid-fourth century Roman arms were approaching Campania.

Relationships with the Latins and the Hernici have not been as good since the Gaul sack of Crustumerium. Major conflict occurred with the Hernici in 362 and later and Tibur and Praeneste in 380. In 338, however, all revolts were crushed, most Latin communities were incorporated into the Roman citizen body along with many Campanians and Volscians. These achievements provided a good foundation for the later conquest of the whole of Italy.

In this hub we discussed a period in which due to a lack of reliable sources and archaeological finds almost nothing is known for sure about the structure and the strategies of the Roman army. In the next hub, The Evolution of the Roman Army, further details will be revealed concerning military units and fighting styles, battlefield tactics and the structural changes of the Roman army, and most importantly the reasons why these battles were fought.