How Guitar Fret Distances are Designed

This study is surely one that a person wanting to learn about the properties of vibrating strings and its application to string instruments should take up, since it includes so much of value, especially as a concrete example of vibrating strings fixed at both ends , its properties and application to the guitar, a very familiar musical instrument. Whether you are a musician, a physicist or anyone who enjoys guitar music, have you ever stopped to think about how to compute the correct fret positions on the guitar fingerboard?

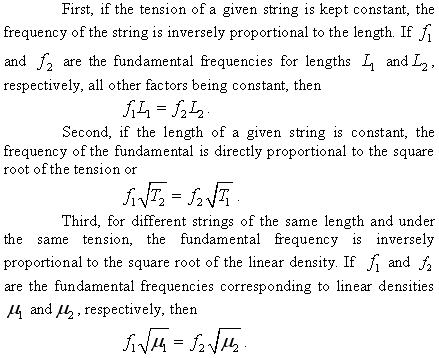

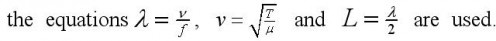

Peré Mersenne (1588-1648) asserted that the pitch of a string is inversely proportional to the length and the square root of the linear mass density, and directly proportional to the square root of the tension:

These mathematical laws obeyed by vibrating strings as outlined by Mersenne can be learned from experiment and this is sufficient for practical purposes.

In this hub, the properties of vibrating strings fixed at two ends is derived by reasoning from some general principles of wide application and the result includes Mersenne’s’ rules, not only would this manner strengthen the validity of the principles, but would give practice in applying them.

Vibrating Strings Fixed at Both Ends

A guitar is a common example of a string fixed at both ends which can vibrate. When we pluck it, the string starts to vibrate in one or more loops. The vibrations of such a string are called standing waves and they satisfy the relationship between wavelength and frequency that comes from the definition of waves:

where v is the speed of the wave, f is the frequency (measured in Hertz, Hz) and λ is the wavelength.

The velocity of a wave depends on the properties of the medium it travels. The velocity of a wave on a stretched string depends on the tension ‘T’ in the string and on the string’s linear mass density ‘µ’

These standing waves may be thought of as the result of waves that travel down the string in both directions, reflected at the end and re-reflected at the other, and so on. The frequencies at which the standing waves are produced are the natural frequency or resonance frequency of the string.

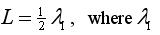

The fundamental frequency, the main pitch you hear, is the lowest tone and it comes from the string vibrating with one big arc from bottom to top. The fundamental satisfies the condition

where λ is the wavelength of the fundamental and L is the length of the freely vibrating portion of the string, it correspond to one antinode (or loop). Since the string is fixed at both ends, so any vibration of the string must have nodes at each end. That limits the possible vibrations of the string (‘mode of vibration’ in simple terms just means style or way of vibrating). The corresponding frequencies at which the standing waves are produced are the natural or resonance frequencies of the string.

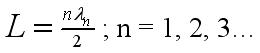

The other natural frequencies are called overtones; when they are integral multiples of the fundamental, they are also called harmonics. In general we can write

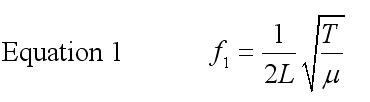

In order to find the fundamental frequency f of the vibration, the equations

Thus, the formula for the fundamental frequency of a string fixed at both ends (Eqn 1).

Equation 1 is the basis for the design of stringed instruments such as piano, violins and guitars. To ‘tune’ a string-instrument, the tensions in the various strings are adjusted until their fundamental frequencies are correct. This equation shows the relationship between the fundamental frequency, length and linear mass density of a vibrating string fixed at both ends.

It includes Mersenne’s rules and accounts for the different masses and tensions of strings of the same length to create different pitches of guitar strings. Individual pitches on the strings are created by pressing down beneath a fret, thus effectively shortening the length of the string.

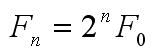

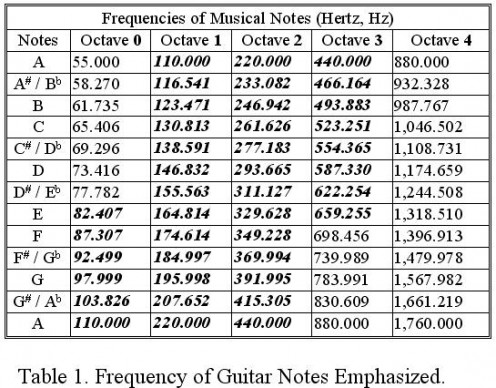

The lowest note on the piano vibrates at 27.5 Hz and the highest vibrates at 4,186 Hz. In guitar, the open 6th string is the lowest note which vibrates at 82.4 Hz (Table 1). This note is called E note denoted by E0. If you double the frequency, you get the note E1, one octave higher than E0 which has a frequency of 164.8 Hz. ‘Octaves’ of a note are just multiples of the original frequency. In general

where F0 is any given note’s frequency and Fn is the frequency of the note n octaves above F0 where n=1,2,3…

The highest note on a guitar of twelve frets is the note E3 (that is three octaves up from E0). From one note up to its octave, the average human ear can distinguished only 12 different tones or notes. So when a chromatic scale (comprising all twelve notes in an octave) is played, we perceived that all sounds between the first note and the last note (the first note’s frequency doubled) are included.

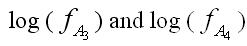

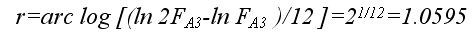

The twelve notes in a chromatic scale are A, Bb, B, C, Db, D, Eb, E, F, F#, G, G#. The equal-tempered tuning is the standard system in music and it assigns the corresponding frequencies to the notes. Tuning is not linear. One has to double the frequency to get the next octave up; one has to quadruple it to get the next octave after that. Consequently, the notes within the chromatic scale are not equally distributed in frequency (or in length). So in general practice, musicians universally assigned A3 to a frequency ofFA3=440 Hz and therefore A4 will be at FA4=880 Hz. We then take logarithms of A3 and A4 frequencies. Next, we mark in 11 equally spaced points between

We then apply arc-logarithms to those points and arrive at the half-step ratio r of notes in the equal tempered tuning. Therefore each successive note in the chromatic scale is r higher in frequency.

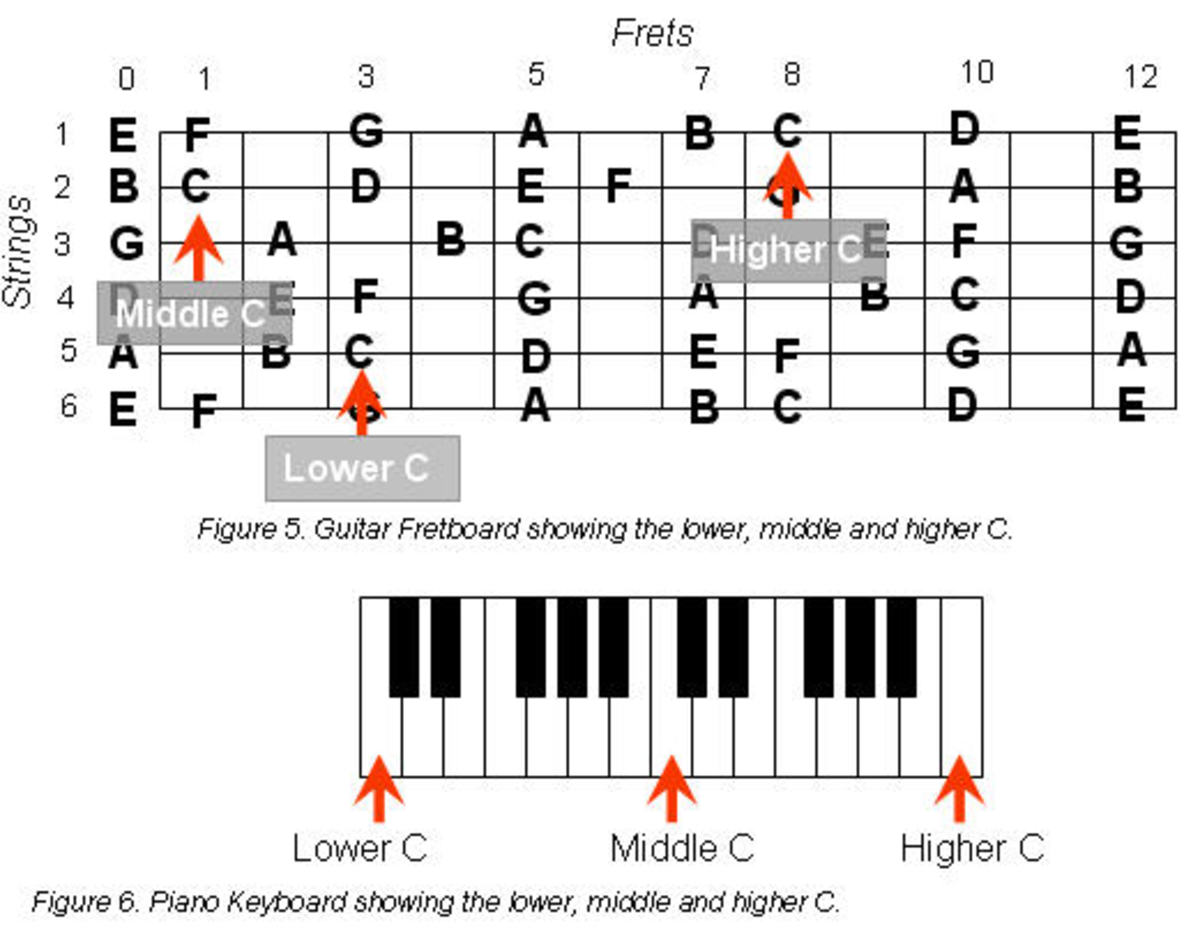

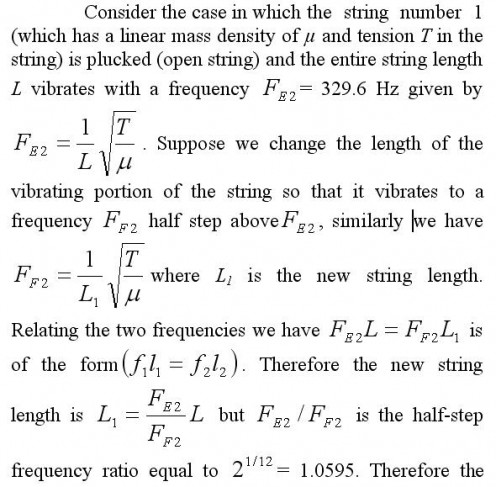

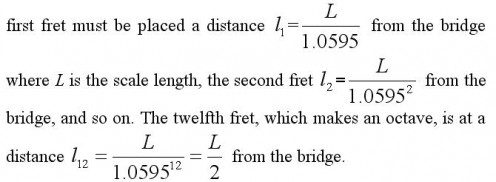

On a guitar, different strings have different linear mass density. The first string is like a thread, and the sixth string is wound much thicker and heavier. The tension in the strings is controlled by the tuning pegs. The length of the open string (also called the scale length) is the distance from the nut to the saddle. When you press down on a string at a fret (assuming tension is constant), you change the length of the string, and therefore its frequency when vibrating. The frets are spaced out so that proper frequencies are produced when the string is held down at each fret. Fig 1 shows the guitar fingerboard.

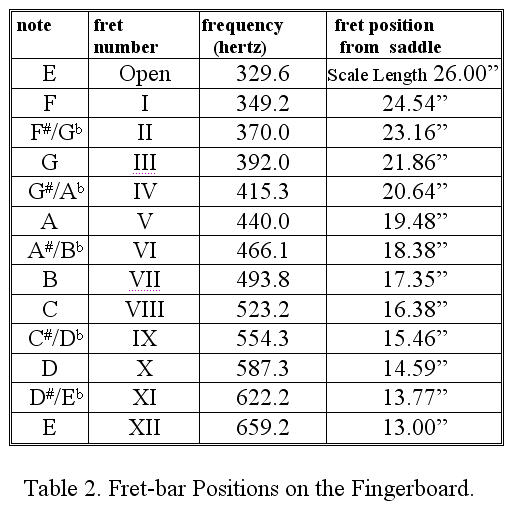

Table 2 shows the frequencies of the notes in the first string and the twelve fret bar positions on the fingerboard based on scale length of 26 inches.