How Do First Nations People Celebrate Indigenous Culture?

Powwow in Kamloops 2012

On the long weekend in August, visitors from all over come to Kamloops to experience the Kamloopa Powwow, held for three days during the first weekend of the eighth month. This is an aboriginal dancing and drumming competition, and a celebration of indigenous culture and heritage in North America. Dancers and drummers flock from all over Western Canada and United States, to dance in the hot sunny grasslands at the confluence of the North and South Thompson Rivers, and vie for prize purses in each category.

During this weekend, the land near the old Saint Joseph Residential School at the foot of Mount Paul and Mount Peter becomes a campground, with tents, RVs and tipis filling the flatlands. The sun beats the land into dust. It hasn't rained for months. Below the hillsides where bunch grasses yellow, the parking lot attendants wear cotton bandanas in triangles beneath dark glasses to keep the merciless dust from caking their throats.

Kamloopa Pow Wow site

Indian Residential Schools

This wasn't always a site of celebration. For years from 1893 until 1977, Saint Joseph Residential school was one of a series of Indian Residential Schools set up by the government of Canada and operated by various religious orders. Required by law to attend the schools, children were forcibly removed from their families and brought to the schools, where they were forbidden to speak their Secwepemc language or practice their customs or spirituality. They were indoctrinated in Christian practices, received little numeracy or literacy instruction, and spent a large part of each day in unpaid domestic, industrial or agricultural labour. Brothers and sisters were separated. Punishments were harsh, cruel and corporal. Food was inadequate, sickness common, sexual abuse rampant, and suicides frequent.

St. Joseph's Indian Residential School

Aboriginal Legend of the Two Wolves

Today beside the entrance to the old Saint Joseph School building, now the Secwepemc Museum and Heritage Park, next to the old photographs of students at the school, the cases of beaded moccasins and historic tools, and the displays of traditional food and medicine plants used in the local Secwepemc First Nation culture, there is a small plaque on the wall telling this ancient first nations teaching story:

An old man was teaching his young grandson about life.

"Inside each one of us," the old man said, "there are two wolves. One is selfishness, greed, anger, spite, jealousy, hatred and fear. The other is kindness, generosity, forgiveness, friendship, love, joy and peace. These two wolves are both very strong. They are both very hungry, and they are always fighting."

The young boy looked up into his grandfather's dark, quiet eyes.

"Which one wins?" he asked eagerly.

"The one you feed."

The Residential School System

The residential school system left a mark on Canadian First Nations that still influences the nation's relationship with its aboriginal people. In recent years community groups have begun working to help residential school survivors and their descendants cope with the inter-generational impact, and to help non-aboriginal Canadians understand what happened and how this colonial form of ethnic cleansing caused such suffering. For more information and lesson plans about this, check the Indian Residential School Survivors website.

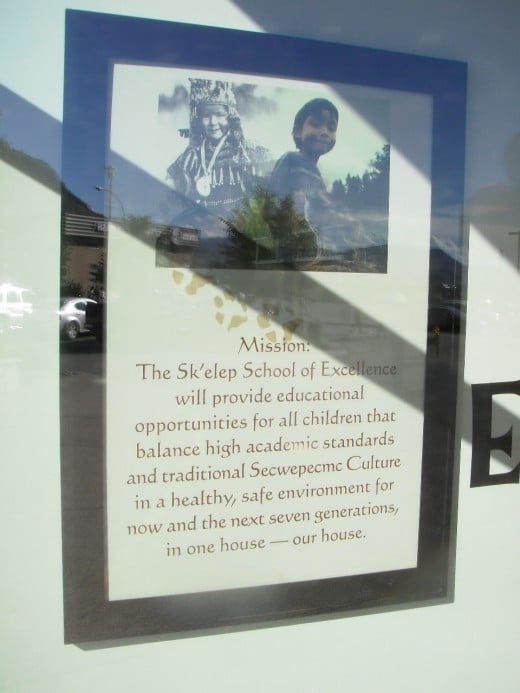

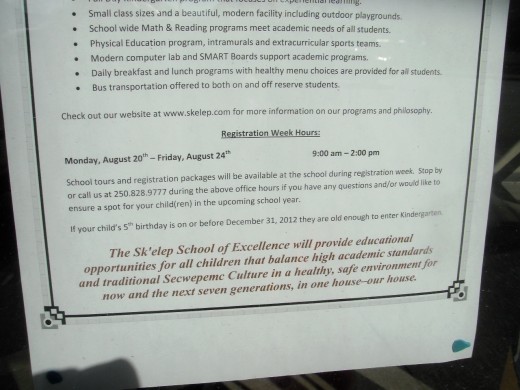

Since the residential schools have closed, individual bands have taken over the education of their own children, enrolling them in band-controlled schools in their community, using national curricula with integrated First Nations culture, language, history and values. Wherever possible, and in increasing numbers, teachers are band members, and language teachers are elders who have retained their native language.

Kamloopa Pow Wow

When dancers and drummers come together in traditional regalia at the site of twin rivers at the foot of twin mountains that have been a sacred meeting ground for their people for thousands of years, they are not performing for tourists. Although all members of the public are welcome, non-aboriginals are in the minority in the crowd. Smells of smoked salmon and bannock mix with hot dogs, children sip Slushies or smokey tea, and cousins play in the crowd, spraying each other with water guns on the hot August afternoon. In all the air of festivity and fun, there is a celebration of the survival of the human spirit as powwows now catalyze pride and not shame in First Nations cultural heritage, and strengthen families.

Families and friends meet up and reconnect at Kamloopa Powwow.

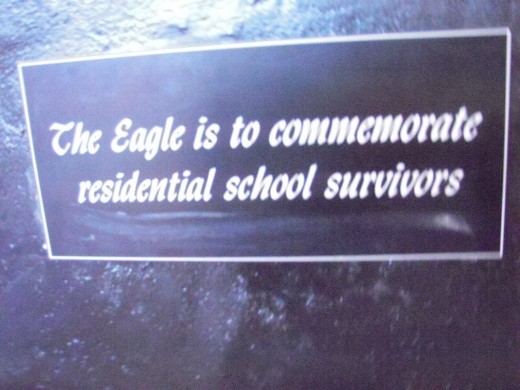

The Eagle Commemorates Residential School survivors

How the Eagle Feather Stopped the Canadian Parliament

In 1990, Elijah Harper, a member of the Manitoba legislature, blocked the passage of a constitutional amendment called the Meech Lake Accord by holding up an eagle feather in the provincial parliament chamber.

The Meech Lake Accord was a negotiation that would have allowed the Province of Quebec to sign the Canada Act of 1982. This was an act of parliament that had repatriated the Canadian constitution from Britain, but it had been done without the consent of the province of Quebec because there was no acceptable mechanism that would allow the government of Canada to amend its own constitution and at the same time protect Quebec's desire for some cultural autonomy and guarantee protection for its French language and heritage within the predominantly English-speaking Canadian Federation.

Harper, a former Band Chief for his Red Sucker Lake Band (1978-1982) and Minister for Native Affairs (1987-1988), recognized historic irony. The people of Quebec had not agreed to the original Canada Act of 1982, and refused to sign it. Now when the English and French parliamentary majorities had found some common ground and terms of agreement, they had neglected to consult with and gain consent of the Canadian First Nations people.

Having found an eagle feather on his path earlier that week and seeing it as a symbol of his ancestors' guidance, he felt empowered to stand in Parliament and speak to the injustice of the Meech Lake Accord, which like many government acts of the past, would dispose of the traditional territories of the First Nations people without their consent.

By initiating a filibuster that extended the debate on the question past its deadline, Elijah Harper, with his Eagle feather, succeeded in blocking the passage of the Meech Lake Accord.

Later that year (1990) Harper won the Stanley Knowles humanitarian Award and was named "Newsmaker of the Year in Canada" by the Canadian Press.

A survivor of the residential schools, Harper graduated from the University of Manitoba, and has recently been working to bring Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people together to find a spiritual common ground and a basis for healing. He is active in the Canadian Aboriginal Land Claims Commission, and still in demand as a public speaker.

Aboriginal dancers brave the August heat

While dancers in traditional dress dance Chicken, Fancy, Jingle and other dances, they move to the beat of the drums and the chanting singers. Their regalia are decorated with eagle feathers, bone, quills, and fur from traditional animals like rabbit, fox, wolf, or wolverine. On their feet they wear moose or deerhide moccasins, sometimes lovingly beaded by an elderly grandmother or aunt. Often the animal masks or headdresses they wear are family icons, handed down through generations. Some have teachings that go along with them.

After the drum beats end, the dancers walk off the field to join their friends and families in the stands, or go to sleep off the exertion in their tent. The dancing goes to midnight, and the visiting carries on later than that.

Kamloopa Pow Wow 2012 Drummers

Native Drums at Kamloops Pow Wow

Around the perimeter of the dancing ground, bands of drummers and singers have come from British Columbia, Alberta, Washington State and beyond to play in turn for the dancers. The drums are made of of hides stretched tightly around a wooden cylinder, and laced together with leather thongs cut from strips of hide. Several drummers beat at once in practiced rhythms with drumsticks as they chant in their traditional language.

In the Crowd at Kamloopa Pow Wow

Like any fair, exhibition or rodeo, many of the events of Kamloopa Pow Wow happen behind the scenes and off the main stage. In the bleachers and along the aisles children play, young dancers in regalia wait for their call, while finishing dancers find their families and share triumph or disappointment. People eat, rest, visit, or shop at the booths of visiting artisans.

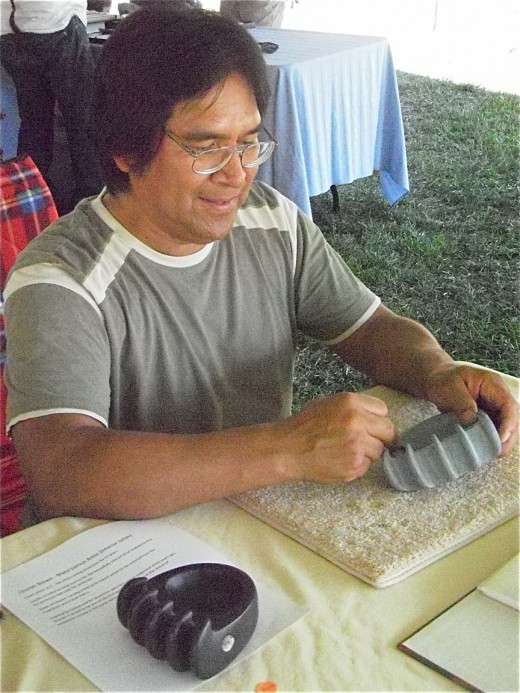

First Nations Art and Artifacts

Every summer in Kamloops, whose nameTK'emlups in the local Secwpemc language means "meeting of the waters," Kamloopa Powwow celebrates much more than dancing and drumming. It's a gathering place where First Nations artists and artisans from around North America come to reconnect with old friends and scattered kin, to sell their paintings, carvings, bead work, jewellery, and clothing. In this forum where twin rivers meet, traditions of the past take on new life and gather strength for moving forward .