Nonsense -- Lewis Carroll's Escape From Reality

Due to early insecurities about himself and later adverse events before and between the composition of the "Alice" books, Lewis Carroll tended to view himself as somewhat backwards and reversed. This could be why he created Wonderland and the Looking-Glass World; using it as a means of escape from the pain of his everyday life. Carrol, born Charles Lutwidge Dodgson on January 27, 1832, had the unfortunate "condition" of being left-handed and underwent failed attempts at a young age to correct it. This might have caused him to view himself as backwards which possibly also caused his stammer, another condition which would continue throughout his life. Carroll may have had a hidden need to visit Wonderland as an exit. Something, perhaps his time in Rugby School or his mother's death, affected his character during his teen years and caused the turnaround. Carroll referred to his father's passing away in 1868, after the publication of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland but before Through the Looking-Glass, as, "the greatest blow that has ever fallen on my life."

Judging from some of Carroll's early verse, he already realized that he had been much happier as a child.

"I'd give all the wealth that years have piled,

The slow result of Life's decay,

To be once more a little child

For one bright summer-day."

Another cause of this could have

been Carroll's unhappiness in school. He Was fourteen years of age when

he arrived at Rugby School, and he really did not fit in. Althought he

wasn't very athletic he tried out for the cricket team and played one

time, after which he was asked to leave the team. He was shy and

therefore an easy target for cruelties from the other students. Carroll

was left with no "privacy or escape."

Given the presented

knowledge of Carroll's torment and the further knowledge of his extreme

shyness could we not conclude that Carroll needed some form of escape?

Carroll simply followed his instincts in reverting to childhood where

the imagination begins. Cathy Newman, who visited Carroll's birthplace

in the county of Cheshire while searching for a Cheshire Cat, said,

"his imagination danced on the boundary between dreams and waking."

Imagination which is simply an extension of dreams is where Carroll

seemed to excel. In fact his definition of insanity seems not to separate

the two:

Query: when we are dreaming and, as often happens, have a dim consciousness of the fact and try to wake, do we not say and do things which in waking life would be insane? May we not then sometimes define insanity as an inability to distinguish which is the waking and which is the sleeping life?

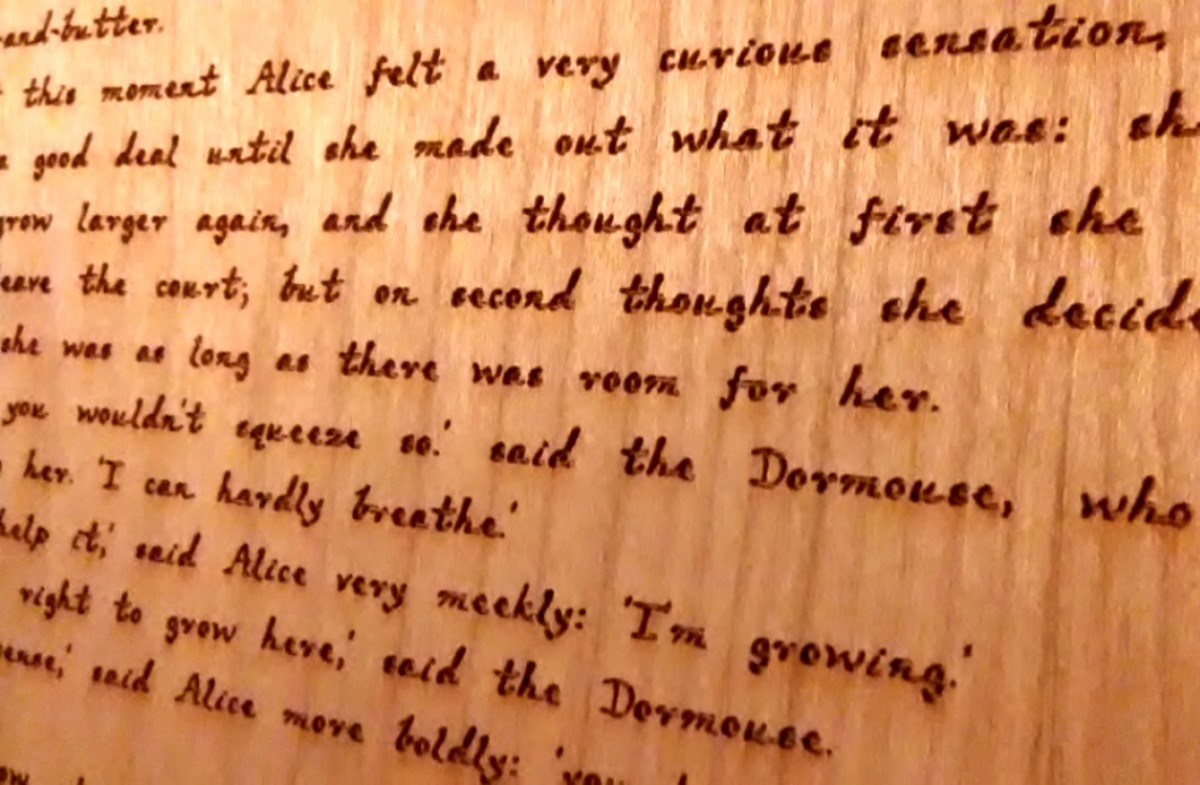

By his own definition Carroll could have been considered insane. He created Wonderland, but few of the characters within are totally isolated from Carroll's reality. In fact, plenty has been said to the effect that the Alice books were the product of Carroll's drawing together years of his own life. Carroll unwittingly developed Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass over a span of twenty years. He slowly formed the basis by giving life to spurts of imagination brought about by past events. These novels were simply a collection of daily occurences strung together with his wit and disguised by imagination. Critics have concluded from the names of some of the animals in Wonderland that Carroll wrote his acquaintances into his stories. Alice Liddell, who was Carroll's inspiration from the beginning, was the protagonist in both books. Alice's real-life sisters, Edith and Lorina, were the Eaglet and the Lory. Carroll's friend Duckworth was dubbed as the Duck, and the Dodo in Wonderland was Carroll himself. This last was a sort of self-imposed criticism on the way he said his name while stammering; "Do-do-dodgson." Carroll also wrote himself into Through the Looking-Glass although fewer critics seem to recognize this more obvious example of his attempts to escape reality. The White Knight says exactly what Carroll would have said had he been in similar circumstances to those surrounding this response to Alice's question:

"What does it matter where my body happens to be? My mind goes on working all the same. In fact, the more head downwards I am, the more I keep inventing new things."

The White Knight is obviously

Carroll's interpretation of himself. A scholar named Martin Gardner,

who studied Carroll said, "Such witty inversion [as found in Through the Looking-Glass] reflects a mind that seemed to function best when seeing things upside down."

Carroll,

being an adult in outward appearance but not in spirit, considered the

value of play unsurpassed. He described it as something that makes man

free and reinforces his joy of life. He went on to say that a mapped

out daily schedule which precludes play is akin to living like a

machine simply performing tasks. Carroll's play was the immersion of

himself into nonsense. Derek Hudson, who authored British Writers Volume V,

said in his book, "nonsense has proved a refreshing bypath of

literature, a kind of detached comedy, an unengaged view of life."

Wonderland seems a perfect playground for Carroll, a place where one

expects the unexpected. In Wonderland nothing is quite as it seems. It

remains a place where the comedy of chaos reigns supreme.

Lewis

Carroll's attempts to excape reality were not always limited to

literature. He had eccentricities which provided the asylum he sought.

He was never particularly willing to receive fame or recognition for

his artistry. Instead he hid behind a pseudonym and was known by his

real name of Charles L. Dodgson to all but children. Carroll was also

very logical and methodical, having written several mathematical

volumes and remaining meticulously organized. He kept an organized file

of every single letter that he sent or received during the last

thirty-seven years of his life. It contained over 98,000 letters when

it was discovered.

Carroll's prime achievement is that he birthed a world of dreams which remains entirely acceptable over time. Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass

were treasures of his time, and remain treasures of our time. They are

still there to be examined for hidden meanings and picked apart by

critics in grand fashion. Lewis Carroll's opinion of criticism was just

as nonsensical as his purely nonsense-for-the-sake-of-nonsense material

was.

"...words mean more than we mean to express when we use them; so a whole book ought to mean a great deal more than the writer means. So whatever good meanings are in the book, I'm glad to accept as the meaning of the book."