- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Literature»

- American Literature

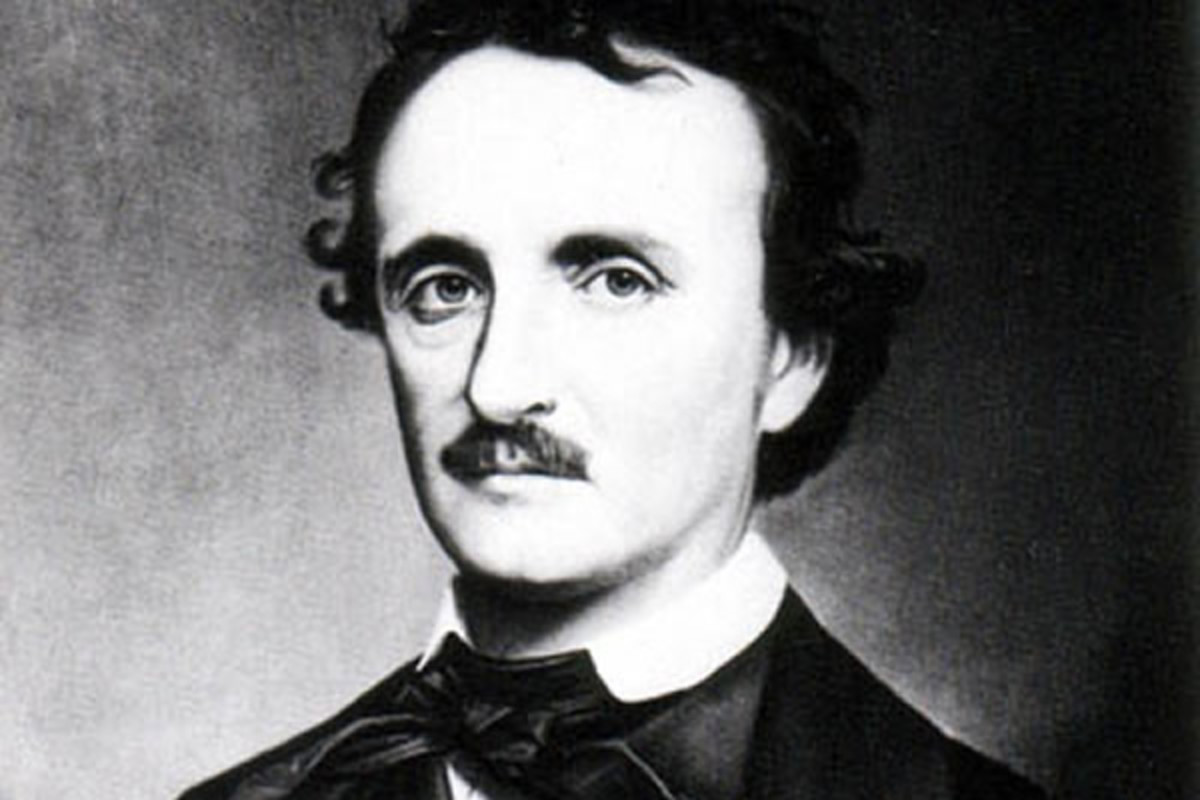

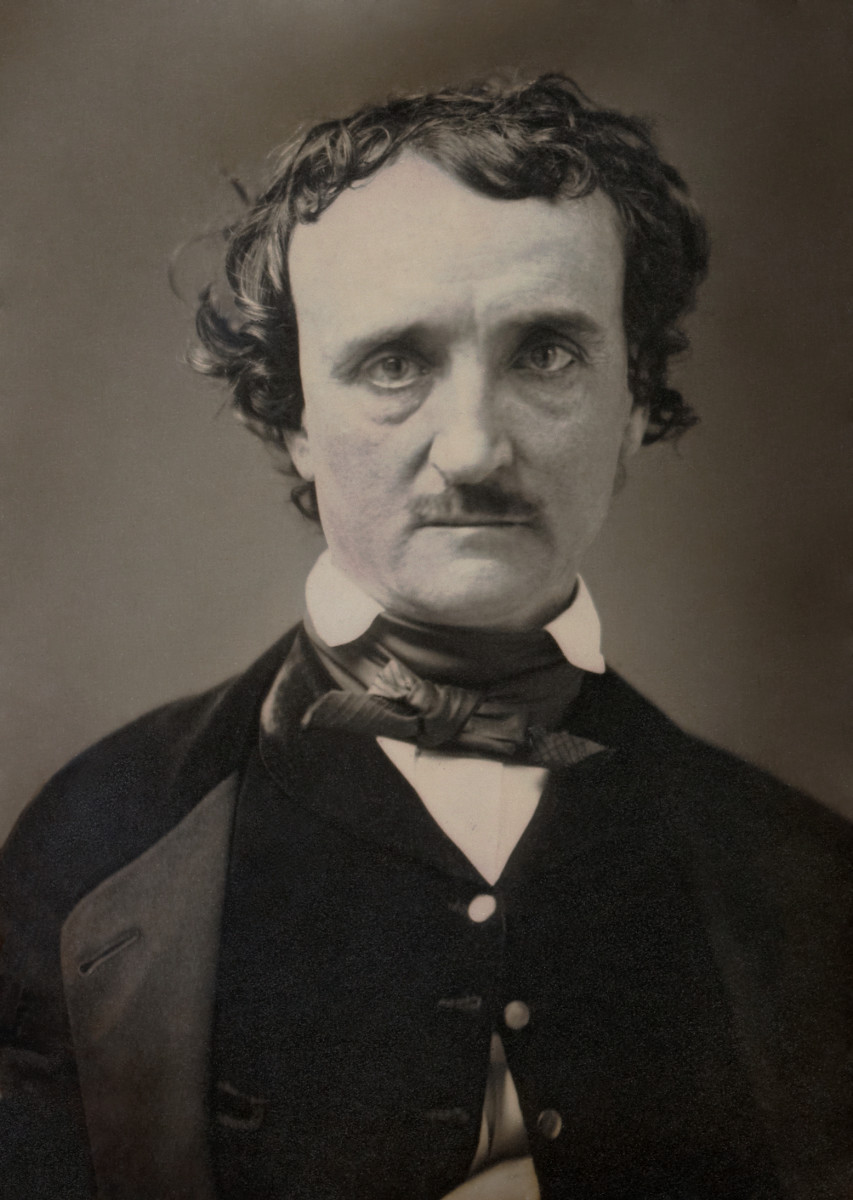

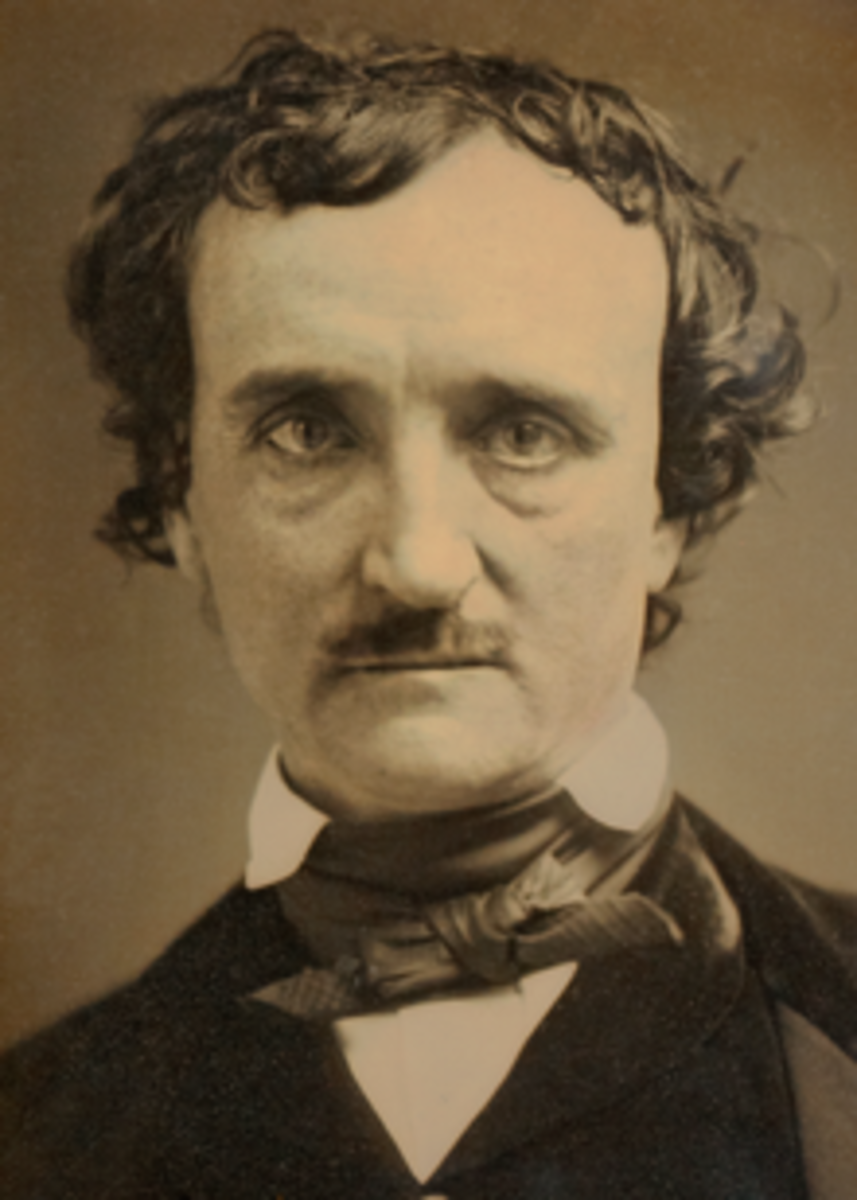

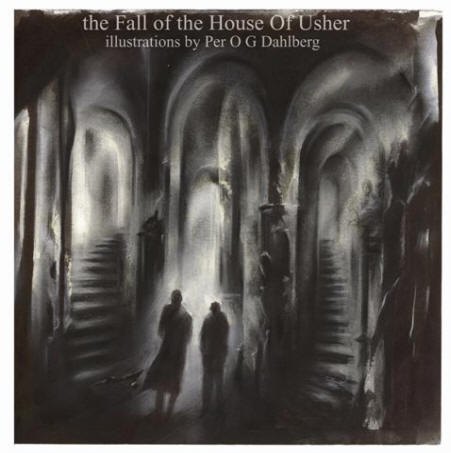

American Classics in Literature: Interpreting the Climax of Edgar Allen Poe's Fall of the House of Usher

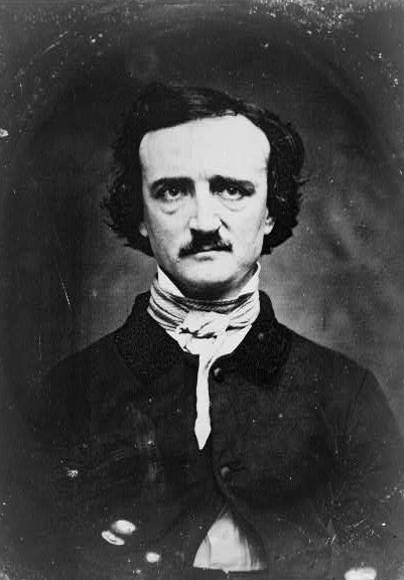

In his “The Philosophy of Composition” Poe tells us that he begins writing with “the consideration of an effect” (1598). Almost all of Poe’s poetry and fiction give evidence to support Poe’s claim that the intended effect, upon the reader, is indeed central to his creative work. “The Fall of the House of Usher” gives example of Poe’s genius in literature not simply in that it is one more example to support Poe’s claim of the primacy of effect, but in the creativity which Poe employs to achieve that effect. The climatic scene of “The Fall of the House of Usher” creates a unique identification between reader and narrator.

This climactic identification is strengthened by Poe’s ability to create a story in which the narrator and the reader share their initial experiences of the House of Usher. In the beginning of the story the narrator, “in a distant part of the country,” receives “a letter” from the House of Usher (1535). This establishes the initial relationship between the narrator and the setting of the story. This relationship resembles the reader’s in that neither has experienced the house before, and neither knows what to expect. In fact, the narrator, not even from the same part of the country where the house resides, gives almost any reader at any time a basis to identify with him in his approach to the house.

Once this relationship is established Poe’s narrator begins to describe how his imagination is run away with by the houses principal feature of “excessive antiquity” (1536). Since the reader cannot see the house, or first hand experience the “rapid increase of superstition” the narrator takes pains to describe his own “singular impression” of “terror” (1536). Poe essentially leads the reader to terror themselves by leaving them no room, within the text, to find grounds for any other such emotional reaction. The ingenuity is not in the repetition of horrifying detail, which Poe supplies the reader and the narrator plenty of, but the ingenuity is in Poe’s giving voice to the narrator’s internal reactions to these details. He has taken simply describing a scary, or haunted, house to the next level by giving the reader the intended emotional responses within the text. Furthermore, he has done one better by subtly suggesting these emotional responses through identification, on the reader’s part, with the narrator.

Later in the story the narrator describes his feelings as “horror, unaccountable yet unendurable” claiming to be rationally aware that his reaction is simply “causeless alarm” (1544). It is almost as if the narrator is answering the readers charge that it is impossible for literature to cause horror. He admits to the reader that this is causeless, and unaccountable. Yet, nonetheless he asserts the reality of his terror. This undermines the rational disassociation from terror on the part of the reader by reminding the reader, as any human well knows that logic does not apply to “the paradoxical law of all sentiments having terror as a basis” (1536). Poe, instead of ignoring the problem that it is irrational to be afraid of something like a story, reminds the reader of how often terror triumphs over reason. He does this again by the subtle suggestions to the reader by way of the narrator’s tendency to self-disclose.

The meticulous description of the house, its effect upon the narrator, and the subtle suggestions that the reader identify with the narrator work together to create the effect of mounting terror, or horror, in the mind of the reader. This is evidence of design, on a more sophisticated level than a simple ghost story, to support interpreting Poe’s work by his self-proclaimed standards. Thus this type of an interpretation is justified, and can be understood to lay the foundation for the story’s climax.

The climax of the story builds upon the relationship Poe has labored since the beginning to establish between the reader and the narrator. The climax takes place on a stormy night. The narrator is in his room, reading a book. This setting, as far as Poe can know, is probably almost identical to the reader’s: alone, in their own room, reading a book. Even if this is not the exact situation of the reader, Poe can safely bet that most readers have at one point been alone in their room at night reading a book. They do not necessarily have to be alone at night while reading “The Fall of the House of Usher” for Poe to achieve his effect, but if they are this only strengthens the intended effect.

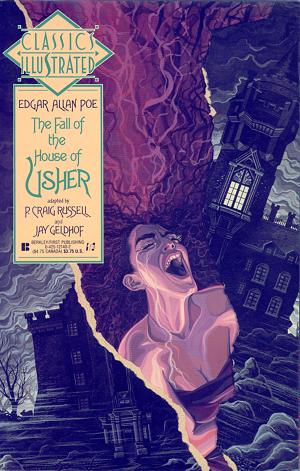

Or how about a collection of Poe's stories?

Once the setting of the climax is described, and its parallel nature, Poe quotes sections from the story the narrator is reading within the main narrative (1545-1546). This ingeniously creates the newest and most tangible parallel between the reader and narrator: they are both doing the exact same thing at the exact same time. No longer is the reader simply imagining a similar first time experience, but actually is performing the exact same task at the exact same moment as the narrator. This is not a distant land, this is not an imagined morale of the house, this is happening in the real world. Poe has created perhaps a unique thing in literature: a narrator and reader engaged, both mentally, emotionally, and physically in the same activity and the same time.

As to the effectiveness of this method of creating effect, Poe’s reputation speaks for itself. “The Fall of the House of Usher” is one of his most popular stories, and this is being written one hundred and seventy years after he wrote the story. Despite any literary critic or criticism that would deny Poe the ingenuity and originality of the application of his philosophy of composition within his writing, Poe is still studied academically. He is still copied in popular culture, and ultimately he is, and will be remembered as, one of the best ghost story tellers of all time. His greatness being not only his unique, disciplined approach to composition, but also the mastery of his application of that approach.

Works Cited

The Page numbers listed in this hub refer to the Norton Anthology of American Literature. I hope this doesn't confuse someone looking for page 1500+ in a volume of Poe's works.

Read More Hubs about American Literature

- The Great American Anti-Hero: Faulkner's Thomas Sutpen as the Uniquely American Version of Joseph Ca

We have a few old mouth-to-mouth tales; we exhume from old trunks and boxes and drawers letters without salutation or signature, in which men and women who once lived and breathed are now merely initials... - Literature You Should Own, But Probably Don't. Part 2: 20th Century American Literature: Postmodern

This is part two in a continuing series of hubs all of which are designed to inform and guide anyone who might want to know a little bit more about the rich tradition of art, letters and philosophy we have... - Kurt Vonnegut's Bluebeard: Writing About Writing For People Who Don't Read

Kurt Vonnegut, one of the most prolific if not best American writers of the second half of the twentieth century, first earned a reputation for himself as a science-fictionist with his early works, The Sirens... - How to win a Nobel Prize for Literature even if you can't sell a book: Reflecting on William Faulkne

When William Faulkner was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1949, his works in the United States had been out of print for almost a decade. While writers like Steinbeck and Hemingway dominated the... - Why I Know Kurt Vonnegut and His Books are in Heaven Right Now

Before anyone writes a nasty comment at the end of this Hub, I want to make sure I clarify that the subject line of this Hub is a joke. It is the same joke Vonnegut made about Isaac Asimov, another great...