- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Books & Novels»

- Nonfiction»

- Biographies & Memoirs

A Commentary on Plutarch's Lives of Cato and Brutus

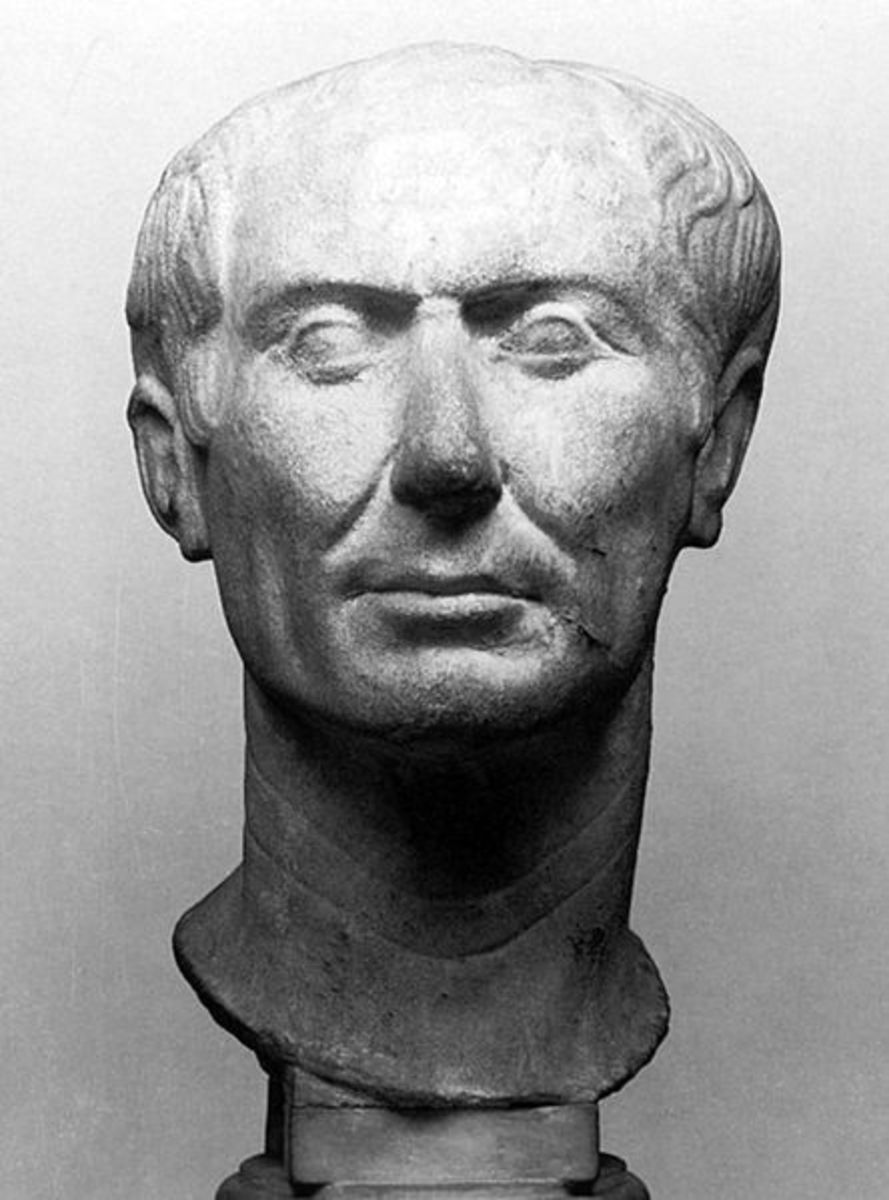

Marcus Junius Brutus (85-42 B.C.)

Stoic Politicians

Plutarch’s Lives of Cato the Younger and Brutus examine the roles of philosopher-politicians in the turbulent atmosphere in Rome around the time of the Civil War. Both Lives function as examples of how good Stoics should behave and what role they ought to play in society. However, Plutarch’s Lives also complicate this thesis by undermining the decisions of their subjects. Cato lived an honorable, honest, and austere lifestyle but he failed to save Rome from “tyranny” because, at least in part, of his unwillingness to compromise his principles even for the greater good. Similarly, Brutus rightly sided against Caesar but stubbornly failed to see the damage Caesar’s murder would bring to Rome. Both men lead exemplary lives, drawing high praise from friends and foes, and both were honest and dedicated public servants who held their own against such prominent and powerful statesmen as Caesar, Pompey, Cicero, and Clodius. Cato and Brutus, with their idealistic principles, ran against the grain of contemporary Roman politics which was mired in partisanship and corruption. Their uncompromising attitude was admirable but also led to their downfall when they set their own principles above the rule of law.

Plutarch suggests that Cato was always destined for public office. Cato was “unbending, impassive and totally steadfast [in] character” and had a “stubborn character” even as a boy (Cato 1). These qualities manifested themselves strongly enough to make Cato a popular leader of the other boys his age, foreshadowing his future prominence. Plutarch establishes him as a man committed to principle through these childhood experiences such as the time he freed a young boy from the clutches of an older one during a party or the time he considered killing Sulla (Cato 2-3). The early incident with Sulla is particularly telling because it sets Cato at odds with the violent and corrupt system of Roman politics. This opposition to Sulla foreshadows Cato’s opposition to other powerful military leaders such as Pompey and Caesar, who were the “beneficiaries” to Sulla’s legacy of violent conquest. As Cato transitioned from youth to adulthood, his qualities made him a dedicated office-holder and a staunch opponent of tyranny and corruption.

Cato sought office as a matter of principle rather than personal fulfillment. Plutarch says that “he was not one of those who enter public life for honour or profit… he chose politics as the appropriate sphere of action for a man of virtue” (Cato 19). In his position as military tribune during the “Spartacus War,” Cato led his men by example and established a close bond with his men (Cato 9). This dedication to good governance would continue throughout Cato’s career.

As quaestor, Cato relentlessly attacked corruption. He began with Rome’s scribes, eliminating slovenly and dishonest men from the system, and even going over the head of the senate in firing an embezzler (Cato 16). Here, Cato set principle of above political expediency, and more importantly the law, by making a characteristically stubborn decision to disregard the senate. According to Plutarch, Cato’s unyielding attitude towards this particular case “won him his battle with the scribes” however (Cato 17). Cato’s opposition to Sulla, established in the beginning of Plutarch’s life, again came into play during Cato’s reform of the treasury. In addition to honestly paying off and collecting debts, Cato sought ought and punished men who had profited by Sulla’s proscriptions making many Romans feel “as if the tyranny of [Sulla’s] days was finally being wiped out… and Sulla himself [was] paying the penalty for his crimes” (Cato 17). Cato’s fight against corruption, however, did not end with his quaestorship, nor was it confined to the legacy of Sulla.

As a senator and as tribune of the plebs, Cato proved a relentless prosecutor of corruption, perhaps to his detriment. According to Plutarch, Cato “trained himself in rhetoric” but resolved only to speak “‘as soon as [he had] something to say’” (Cato 4). At this stage of his life, Cato certainly had a great deal to say. He opposed Caesar’s argument for leniency toward the men implicated in the Catiline Conspiracy, arguing successfully for the death penalty (Cato 23). Although Plutarch frames Cato’s actions as just, executing Roman citizens without a trial was a violation of their rights and was also quite harsh, even by Cato’s standards. By painting Julius Caesar’s motives for clemency as suspect, Plutarch tries to justify Cato’s hardline stance. Nevertheless, this episode suggests that Cato’s idealism took him too far. Once again, Cato’s principles trumped Roman law, this time in a capital case.

Cato proved a capable and careful administrator even when he did not want to hold office. After Clodius passed a bill forcing Cato to become the provincial administrator of the newly acquired territory of Cyprus, Cato discharged his mission with his typical honesty and brought back handsome revenue to Rome (Cato 34-39). Principle was more important to Cato than partisan politics and wealth and honor for Rome meant more to him than personal gain.

While most Roman politicians fought partisan battles, attacking corruption only in their enemies, Cato did not spare his friends in his pursuit of justice. Early in his career as tribune of the plebs, Cato opposed his friend and admirer, the censor Lutatius Catulus, during the prosecution of a scribe and even threatened to have Catulus expelled from court (Cato 16). Later, Cato opposed his friend Cicero when the orator was criticized for destroyed Clodius’ record of the tribunate (Cato 40). In both of these cases, Cato set principle above personal friendship.

Cato’s ability to draw admiration and even friendship of his rivals was a running theme throughout his life. When he was tribune of the plebs he prosecuted Lucius Murena for bribery during the consular election but conducted his prosecution in such an honest and proper manner that he won the friendship of Murena himself who called on Cato for advice after his acquittal and election to the consulship (Cato 21). Recognizing Cato’s power, Pompey himself sought a marriage alliance with him, through Cato’s nieces or possibly Cato’s daughters (Cato 30). Even Julius Caesar, Cato’s bitter enemy, reportedly said that he only faulted Cato for his suicide because Cato “‘begrudged [Caesar] the granting of [Cato’s] life’” (Cato 72). These incidents only serve to make Cato’s virtue stand out even better and illustrate the Roman affinity for Stoicism in general. Even those who did not adhere to Stoic principles were able to admire them in others.

Cato’s Life also highlights the degree to which Roman politics had sunk. One particularly telling incident occurred during Cato’s praetorship. Plutarch says that accepting bribes from politicians running for office had become “a matter of daily routine” and that it was necessary for Cato to oversee the consular election of that year personally to prevent the candidates from bribing their way into office (Cato 44). Because of his honesty, Plutarch claims that “all the big men were Cato’s enemies” (Cato 45). To be sure, this intense opposition emphasizes Cato’s virtue, but it also demonstrates the level of corruption in Rome that a man should be so reviled for his honesty.

For all Cato’s political idealism, the eminent statesman’s personal life was marred by scandal. Throughout his life, Cato was reported to go “without shoes or tunic” even on the most serious occasions and also was accused of drinking to excess (Cato 44). The role of politician and philosopher collided. While as a politician, Cato’s public image was important, as a philosopher, Cato rejected “the usual lifestyle and habits of day” and sought to “talk to the philosophers over the wine” (Cato 6). The behavior of the women of Cato’s family and his relations with them also drew him harsh criticism. One of his sister’s had an affair with Caesar, the other was separated form Lucullus due to her “immoral behavior” (Cato 24). Cato divorced his first wife, Atilia, “for her bad behavior” (Cato 24) and then divorced his second wife, Marcia, so she could marry a friend of his (Cato 25), only to remarry her years later, some claimed for her money (Cato 52). More problematic than all of this, however, was Cato’s death.

Cato’s death was a radical departure from his Stoic principles but it was also in keeping with the same stubborn nature he had always exhibited. In spite of the pleadings of his son and his companions, Cato killed himself before Caesar could capture him (Cato 68-70). Although a good Stoic would have been more justified in fighting to the death or surrendering and accepting fate, Cato stubbornly refused to give in to Caesar.

Brutus resembled Cato in many respects. He was connected to Cato and many of the notable figures at the time and faced similar challenges in reconciling Stoic philosophy to the realities of politics in first century Rome. Like Cato, Brutus was “well trained as a forensic orator” and became known for his brief but effective rhetorical style (Brutus 2). Along with Cato, Brutus opposed Caesar’s rise to power in Rome and fought on Pompey’s side in the Civil War. Ultimately, Brutus made an even more radical stand against the changing times in Rome by murdering Julius Caesar.

While Brutus was certainly manipulated by Cassius, he still acted based on his own principles. Plutarch says that Cassius “inflamed Brutus’s feelings and urged him on” to killing Caesar out of Cassius’ own personal hatred for Caesar (Brutus 8). The influence of Cassius was not enough however to sway Brutus. Only combined with “a whole succession of hints and written appeals” did Cassius’ urging convince to lead the conspiracy against Caesar (Brutus 9). According to Plutarch, Brutus “acted only upon due reflection and a moral choice based on practical reasoning” (Brutus 6). It was this reflection that marked Brutus as a good Stoic.

Brutus’ choice resembled the choices Cato made during his career. Like Cato, Brutus put principle above personal relations. He took Pompey’s side during the civil war, in spite of the fact that Pompey had had his father executed, because, according to Plutarch, “Brutus believed that he ought to put the public good before his private loyalties, and… was convinced Pompey’s cause was the better one” (Brutus 4). Brutus’ sense of duty, resulting from his Stoic philosophy, forced him to overcome his personal feelings.

Brutus was no more susceptible to the corruption in Rome than Cato. Plutarch says that Brutus “could not easily be persuaded to give his support to anyone who sought it as a personal favor” (Brutus 6). The emphasis Plutarch puts on Brutus’ refusal to use his office to grant favors indicates how common this practice was in Rome. Brutus’ refusal also marks him as a good Stoic who, like Cato, refused to compromise principles for friendship.

In his decision to kill Caesar, Brutus followed Stoic principles rather than personal feelings or self-interest. While Cassius had a personal vendetta against Caesar, Brutus had a valuable and potentially beneficial friendship with Caesar. Caesar was “concerned for Brutus’s safety” and “gave orders… that Brutus” was not to be killed during the Civil War (Brutus 5). After the war was over, Caesar even gave Brutus the governorship of Cisalpine Gaul (Brutus 6). Plutarch suggests that had Brutus not been drawn into the conspiracy “he might easily have become the most influential of all Caesar’s friends and exercised the greatest authority” (Brutus 7). However, Brutus “opposed Caesar’s rule” and this opposition was more important that his personal relations with Caesar (Brutus 8). It was Brutus’ principles which ultimately led him to kill Caesar.

Brutus moved in the same circles of the Roman elite as Cato and had close personal ties to many prominent Romans of the time. Brutus’ mother, Servilia, was Cato’s sister and carried on an affair with Julius Caesar, which, Plutarch suggests, may have meant Brutus was literally Caesar’s son (Brutus 5). Brutus also married Cato’s daughter Porcia (Brutus 13) and ideologically aligned himself with Cato, Cicero, and their allies. Brutus was also a great leader of his fellow Roman elite. According to Plutarch, the conspirators only “agreed to join [Cassius] on the condition that Brutus became their leader” (Brutus 10). Plutarch also says that Brutus’ reputation drew many important men into the conspiracy (Brutus 12). This respect that other Roman elites had for Brutus is yet another source of evidence for the general respect Romans had for Stoicism and principled living.

Regardless of his good intentions, Brutus was wrong to kill Caesar. By setting political principles above the law and even friendship, Brutus began another cycle of violence in Rome and even further cemented the political assassination as a means of controlling leaders. The fighting between the supporters of the conspiracy and the supporters of Mark Anthony and Octavian and Octavian’s proscriptions following his victory were direct results of the violence unleashed by the murder of Caesar. Facing defeat, Brutus, like Cato before him, forsook his Stoic principles and chose suicide over capture by his enemies.

Through the Lives of Cato and Brutus, Plutarch demonstrates the qualities Romans considered virtuous and also the difficulties faced by men trying to live virtuous lives in a corrupt society. Both Cato and Brutus failed to apply their Stoic principles successfully to remedy society and both were ultimately destroyed by their inability to compromise their principles.