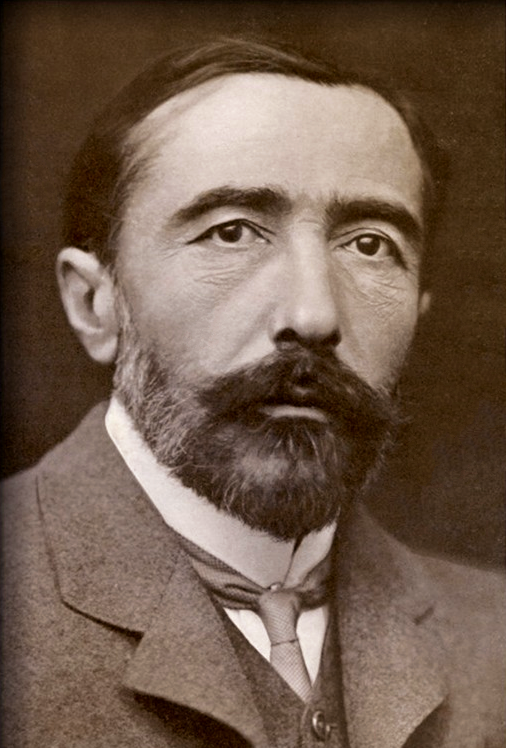

Does Prejudice Render Joseph Conrad's "Heart of Darkness" Valueless?

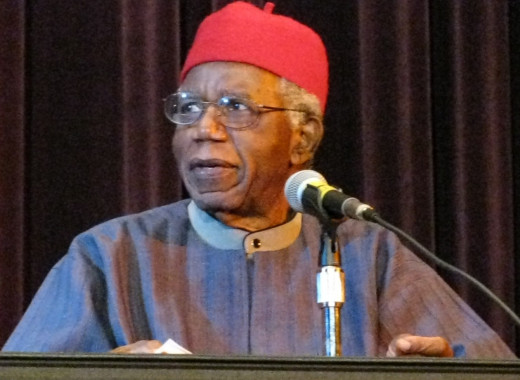

In the late, great Chinua Achebe’s article “An Image of Africa” on Joseph Conrad’s short story “Heart of Darkness,” the author argues that “Heart of Darkness” is hateful, racist, plays into Western myths of Africa which still exists, and as such forfeits its high position in society as “permanent literature” and as art. Surely, what stylistic praise anyone could heap upon the novella, it remains hard to disagree that “Heart of Darkness” is uncomfortable to read. Certainly the story was meant to be an uncomfortable one—a nightmare, an admonition of corruption—but it is also uncomfortable for reasons that do not seem to be intended within the text.

“Bloody racist” is the term that Chinua Achebe bluntly, but accurately uses to describe Conrad (9). Achebe uses biographical evidence (Conrad’s personal account of his first encounter with a black man) to support this, but the text of “Heart of Darkness” itself supports this, so there is no need to go outside the text. It describes African characters as only being fine “in their place”; it describes the humanity of the Africans as “ugly” and primitive; it describes the white pilgrims as being like “sane men” in an “outbreak in a madhouse.”

Clear oppositions are set up in this text between Europe and Africa in ways that cast Europe as the seat of civilization, holiness, language and sense, and force Africa to be seen as the opposite: chaotic, wicked and insensible. In this sense, for Conrad’s purposes, Africa might as well be hell and its resident’s demons; or perhaps the surface of some unknown and inhospitable planet and its occupant’s alien; or, perhaps most nearly to the way the text treats its setting and people, Africa might as well be a monster and its people the monster’s limbs and eyes. He achieves his end by rendering the African people in his story voiceless—or rather, they speak few lines, and in all other instances are reduced to howls and grunts. A society that is merely different from the one Conrad comes from is reduced to one of madness, disorder, and unholy magic.

As such, Conrad spends much more of his time concerned over the corrupting influence the African environment is having on himself and on others. Early on in the story, the question is raised about how much a person’s mind could change from traveling to Africa. “I felt,” the narrator Marlow relates early on in his time there, “I was becoming scientifically interesting." And the bulk of the third part of the story is consumed with the character of Kurtz, who Marlow insists on calling “a remarkable man” even after seeing him try to fashion himself as a god, steal greedily and be the cause of many deaths. There is disgust for what Kurtz did, certainly, but the mourning there seems more about his personal fall into immorality—not the damage he caused to others. His last words: “The horror! The horror!” are lingered upon and repeated. The story is about Kurtz’s personal horror of corruption and Marlow’s personal horror of witnessing it. The story is not about the horror that they, and their company, and their governments, brought to the area. It is not about the harm done to the Africans, it is, as insane as it seems, about the harm that Africa has done to them.

Myth-making is going on here, and, as Achebe points out, this kind of thing “is not new” (2). By casting Africa as a place of moral “darkness,” Europe is able to bolster itself, to feel superior and right. It is by this process that invaders can view themselves as victims—and thereby justify their invasion to themselves. Even in a rare moment where the character of Marlow seems to mourn for the African man who steered the steamboat for him, there is this superiority. “I had to look after him,” Marlow explains, “I worried about his deficiencies, and thus a subtle bond had been created." But Marlow does not make this bond one about equals. It is a paternalistic bond. It is the same kind of thinking that leads into the real-life example Achebe points out in his article of Albert Schweitzer saying: “The African is indeed my brother but my junior brother” (8). Concern framed in this way becomes nothing more than an excuse to take control of someone else’s destiny away.

The question Achebe comes to, after going through all this, is if “a novel which celebrates this dehumanization, which depersonalizes a portion of the human race, can be called a great work of art” (9). For Achebe, the answer is no. “No matter how striking his imagery or how beautiful his cadences fall,” Achebe declares, “such a man is no more a great artist than another may be called a priest who reads the mass backwards or a physician who poisons his patients” (9). But is there value in this flawed and prejudice piece of literature?

The answer depends a great deal upon the framing. Understanding the entrenched, unquestioned racism that permeated even talented minds and lofty thinkers can no doubt help in the effort to examine the prejudices of modern times. Achebe points out that “Heart of Darkness” is not the only example of its time of this sort of myth-making. He also relates a few examples from his own life that more than suggest that myths of Africa have survived into the modern era. Banishing “Heart of Darkness” from the literary canon would not, therefore, wipe away that ugly myth—not then, not now. The only way to actually combat these beliefs is through rigorous self-examination which can be aided by understanding the insidiousness of the beliefs of the past—and how those beliefs inform present attitudes. “Heart of Darkness” is, therefore, important. It is not nice, it is not pleasant and its prejudice may outweigh any considerations of its stylistic qualities—may make it less what the modern culture thinks of as “good” art. Yet, it is a tool in the toolbox of dismantling and understanding the prejudices it preaches. But this can only be achieved with an active and suspicious reader who does not play Conrad’s game or take him at his word.