Eroding the Veneer

By Nils Visser

On the whole I tend to advise my kids to focus on the characters when reading. What are they doing and thinking, how are they solving their problems? What’s happening to them?

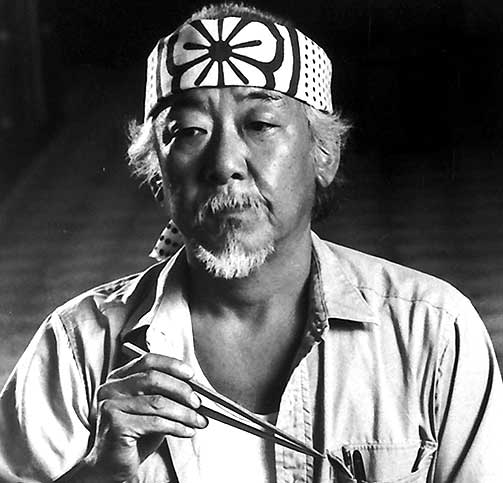

Setting, I tell them, is usually just a backdrop. Even more so when we take archetypes into consideration. Take the formula Merlin = Gandalf = Panoramix = Menaures = Obi Wan Kenobi = Miyagi = Dumbledore for example, and the backdrop really does shrink into the background. The wise old sage is here and the content of his message and fortitude of the example he sets, matter a great deal more than whether or not the sage is a wizard orchestrating royal adultery, a druid in a Gaul village, a venerable knight in outer space, a martial arts teacher in a Californian suburb or the Headmaster of a school of wizardry. The moment the sage appears, we recognize him and are on familiar territory, regardless of where that territory is and what it looks like.

In acknowledging the comment made in the last lesson that heroes in fantastical quests are usually young boys or men, it’s interesting to note that the wise old sage is almost always an old man and seldom a woman, barring perhaps Marion Bradley’s works like Mists of Avalon where women are allowed greater access to wisdom, acknowledged by the weaker male Merlin figures.

Back on track: There are books in which the setting cannot simply be pushed to the background. Aforementioned favourites such as Bridge to Terabithia and The Eqypt Game make partial use of the setting, both contain escapism from the trappings and restrictions of, respectively, a rural and an urban environment. The setting is important up to that extent, but both rural and urban setting could be moved about freely to almost any rural or urban location in the States, or even Europe for that matter, without affecting the stories a great deal. Opposites of these examples can be found in To Kill a Mockingbird and Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. The Mississippi setting of these locations in the Interbellum is of such importance to the narrative that the stories would simply collapse without the setting.

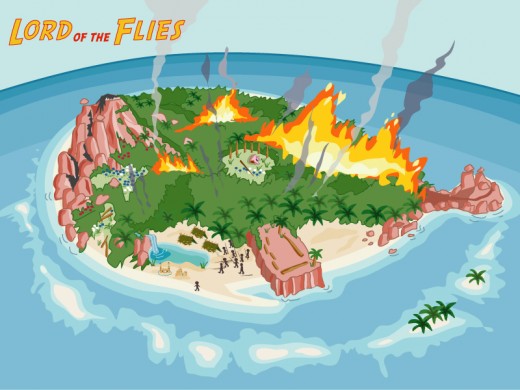

Taking it a step further, one could launch a very convincing attack on my casual dismissal of setting simply by referral to titles such as Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland and William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. However, in these cases I would go as far as to argue that the setting actually becomes a character in its own right. This is personification taken to the extent that our Celtic and Germanic ancestors experienced their surroundings: As living entities with a soul, spirit and defining characteristics. Wonderland, with its very own rules of physics, is very much present in the Alice in Wonderland story as a seemingly sentient organic being that seems to orchestrate the narrative, presenting or denying Alice with options.

As mentioned before, some people do feel very disturbed by this story, and Wonderland’s role as a living character may be connected to this, all the more so in the Netherlands. This latter isn’t surprising perhaps, seeing that the Dutch live in an mostly artificial country which is almost entirely shaped by man’s hand. A Nepalese anthropologist, come west to study inhabitants of the country, once wrote that the weather was a major source of conversation in the Netherlands because the Dutch were most frustrated by the fact that they couldn’t control it and they do like to control things. The Dutch will personify water happily, knowing well the latent power and unpredictability of their old liquid friend and foe, but are uneasy when land is personified. Perhaps because their control of the land allows them to channel the water and security lies therein, decidedly not in land doing as it pleases. People in England and Ireland seem much happier with Wonderland as living and conscious being, after all, England is a country where the Fey fires still glow on the summits of old hill forts on certain nights of the year and Ireland is a country where trees have a sense of humour and will on occasion cross the road to befuddle regular commuters (or so I’ve been told over a pint of Guinness) and some folk still set out plates with food for the Sidhe.

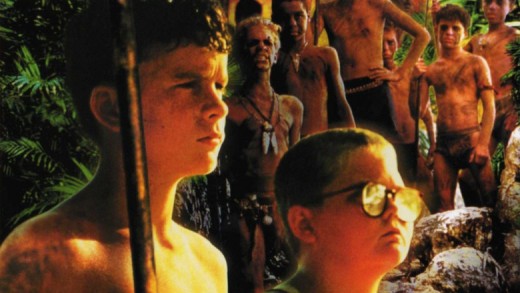

Well, if Wonderland frightens you, best to stay away from Lord of the Flies, because the setting is far more dark and ominous. Sure, Golding’s main message is that real evil resides in people: in the form of fear; the evil deeds that people will commit or tolerate in order to avert that fear; and the masterful manipulation of fear by tyrants. At first there is no real “Beast”, it exists in the minds of the boys only and then is born by their collective projection of it, at which point it becomes clear that they themselves are the Beast. None-the-less, the island on which the boys are stranded is ever present in the background as a silent and brooding witness and it clearly has a dark and evil side (the jungle) which throws a looming shadow over the opportunity to adhere to civilization.

There where the distinction between the island as physical environment and living host as well as good and evil becomes blurry, i.e. specifically in chapter eight where the most spiritually minded character, Simon, conducts a conversation with the Lord of the Flies, a teacher might have to guide students through the scenes step by step. When I read this book as a youngster I got the savagery quick enough, the more abstract aspects were puzzling, partially because Golding keeps his personification of the island and analysis of good and evil fairly subtle, in comparison with, say William Shakespeare. The latter, in The Tempest is quite happy to present us with physical representations of his island, the “good” being embodied by the sprite or spirit Ariel and the “bad” embedded in the figure of Caliban.

In the case of Lord of the Flies personification turns the island into a sentient character, from a broader literary perspective the island could also be said to have a thematic nature, or even be part of the genre sometimes called Robinsonade, originating from Daniel Defoe’s 1719 novel Robinson Crusoe. This particular “genre” covers all sorts of different stories linked mostly -or even only- by the fact that it involves a person or group of people stranded on an island, usually uninhabited.

The notion of placing a story on an island is incredibly popular in storytelling. As a narrative device it is a useful way of cutting a person or group of people off from outside interference. Plots aplenty, perhaps the people on the island want to get off, perhaps they want to keep others off, perhaps they want to lure others there etc. Quite possibly there is an attempt to colonize (Robinson Crusoe, Prospero’s dominion over the original inhabitants in The Tempest) or build a brave new world, meant to be an improvement on the old (Alexander Garland’s The Beach and (figuratively) Paul Theroux’s The Mosquito Coast). In the latter type we’ll usually find that the road to Hell is paved with good intentions and the road to Heaven full of tempting pitfalls, which then becomes the story.

Very commonly there is an implicit acceptance that the physical separation of the island from the rest of the world means that the island can have its own set of rules, both rules of a social nature, usually set up by the newcomers (precisely what Ralph and Piggy try to achieve in Lord of the Flies) as well as entirely new rules of physics and/or reality.

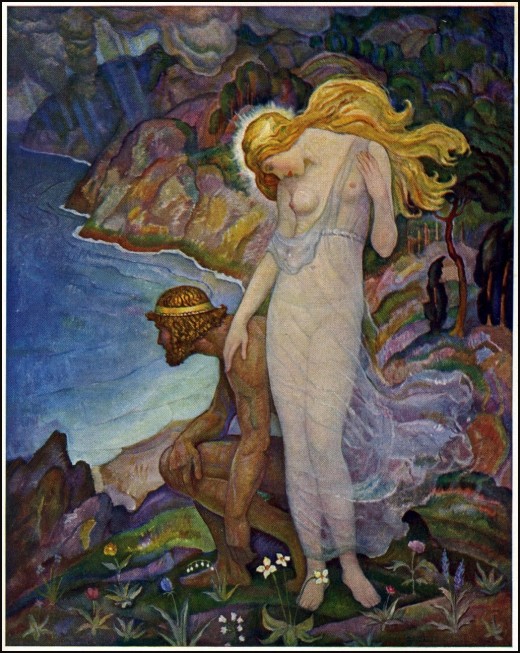

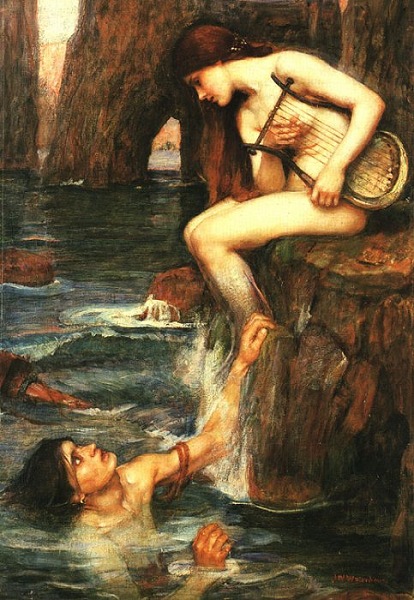

This latter characteristic of islands has a long literary history, easily surpassing that the publication of Robinson Crusoe in 1719 by two millennia. It started in roughly 800 BC, when Homer wrote of Odysseus telling young Nausicaa and her parents how he arrived on their island of Scherie. This is The Odyssey, sequel to The Iliad. The latter is the tale of Troy and its defeat by the Greeks, the former the story of the ten year journey undertaken by Odysseus in attempt to go home to Ithaca and this tale is full of islands brimming with the fantastical. Odysseus and his crew visited the Lotus-eaters on one island, were captured by Polyphemus the Cyclops on another, hazarded the Laestrygonian cannibals on yet another island and managed to bypass the enticing Sirens by the shores of the Siren lands and then his crew made a pretty fatal decision on the island of Thrinacia, one which would cost all but Odysseus their life.

Not all was hardship, Odysseus spent a year on Circe’s island as her lover, and a full seven years as a captive on Ogygia, where he more or less became Calypso’s sex slave, something which he didn’t appear to object to with any due haste, though he was somewhat worried that his wife wouldn’t remain faithful to him.

More iconic island imagery from Greece is Plato’s Atlantis, albeit in the lost world and/or perfect society category rather than that of shagging nymphs (one would think the latter two form a fine combination?).

One need not travel far for tales of lost islands, Albion and Eire will supply both in abundance, even though the heyday of the Fey was, to use Chaucer’s words, “In olde dayes of the Kyng Arthour, al was this lond fulfilled of fayrie; I speke of many hundrid yer ago; But now can no man see non elves mo.” (Wife of Bath’s Tale) people in the Celtic fringe speak yet of “Green fairy islands, reposing, in sunlight and beauty on Ocean’s calm breast” (from Welsh Melodies).

These green meadows of the sea include the Welsh Gwerddonau Llion and the Arthurian Avallach (Avalon) as well as Lyonesse off the Cornish coast and the Irish Uí Breasail as well as Falias, Gorias, Murias and Findias, where the Tuatha De Danaan hail from.

These isles have in common that they are said to be home of the Fair Folk (Sidhe) and appear and disappear in the manner of a Cheshire Cat.

By-the-by, should you wish to mine the rich and fascinating Celtic lore and seek an accessible entry for school kids you could do much worse than employ Susan Cooper’s the Dark is Rising series. The first of the five books, Over Sea, Under Stone is less epic in scope and more suitable for young readers who seek something a bit more substantial than the Famous Five. The other four books, The Dark is Rising, Greenwitch, The Grey King and Silver on the Tree are suitable for older children and young adults. Cooper makes much use of ancient beliefs and Celtic lore which can lead to further in-depth exploratory assignments. It might also be interesting to have five reading groups reading one book each and informing other groups about the book they read.

Another novel which is reasonably suitable for school, though may require an abridged version and some explanation as to what elements of society were being satirized is , of course, Gulliver’s Travels, written by Jonathon Swift and published in 1726. Here we have island after island populated with the fantastical and kids (as well as adults) tend to specifically like Gulliver’s adventures in Lilliput and Brobdingnag, offering potential appealing creative writing assignments.

Within the context of the ethnic origins of students at many schools in the larger cities it might also be worth the effort to devote some time to a chapter or so from Sinbad the Sailor, not quite English literature (ahem) but it can be squeezed into a thematic approach of islands and will be appreciated as a nod of recognition of cultures other than the mainstream western one.

A teacher would be wise to formulate an opinion on the legitimacy of The Blue Lagoon (Book and multiple film adaptations). Personally I think it’s too soppy but it’s a favourite for many people and who am I to deny them their fun?

For the more gory-minded Survivor Type by Stephen King is a short story about a shipwrecked doctor who amputates parts of his body so that he has something to eat. A splendid opportunity of course for interesting discussions, you’ll find that your average teenager needs no stimulation to have and discuss an opinion on this story and imagine themselves in a similar position.

Further reading material in the form of books would be Alex Garland’s The Beach. Don’t moan if you’ve only seen the movie, the book is far better and there’s a good abridged audio book available. Basically, The Beach, is a modernized version of the Lord of the Flies, it’s just that the kids are older and have sex, drugs and rock-n-roll on their island before the inexorable slide into madness.

If advanced students ask for a recommendation then the Life of Pi is the perfect suggestion, though we’re talking intelligent seniors here, not clever Freshmen or Sophomores.

A fine class activity would be BBC Radio 4 Desert Island Discs. See if you can find an episode in which the person being interviewed is likely to be known and appreciated by the students, devise some questions and you have a good start-up. After that, they can have their own interviews regarding the eight records, one book (you could make it more) and one luxury inanimate object which they would like to have with them on an uninhabited island. You might be surprised how passionate students can get with regard to this assignment.

A final recommended activity would be to devise an audio/visual lesson in which you show a segment of Survivor, the CBS TV reality series in which contestants attempt to remain the last man standing on remote islands or part of the first episode of Lost, a TV drama series about the survivors of a crashed airplane. Add questions, allow a bit of discussion and then turn to the series Flight 29 Down, a TV reality series on Discovery Kids about modern teenagers who enact surviving a plane crash on an island in the South Pacific. Devise a nice writing or speaking assignment, and with a bit of luck they’ll go home and watch the whole rest of the series in their own time. Good for their English, and a lot more healthy than the omnipresent pulp on telly. (http://www.ovguide.com/tv/flight_29_down.htm)

The very drift into ample lesson materials and ideas for the concept of a Robinsonade theme reflects upon the fascination readers young and old have with the idea of an uninhabited island to play with. Moreover, this theme allows you to cater to various interests, one student might be much more interested in the social interaction between a group of people sharing a similar ordeal, another in the Romantic appeal of being stranded on a tropical island with a special someone, or a whole host of Tahitian beauties if you happen to be a mutineer on the Bounty. Yet another may be concerned with survival and those interested in Fantasy tend to drool when given a blank map of an island and told to create a world.

However, there’s another theme in Lord of the Flies that will also appeal to many students, specifically boys, and that is savagery. An essential feature of a Robinsonade is the man versus nature struggle. It’s back to basics and one needs to survive, how long will the thin veneer of civilisation last?

Golding poses the crucial question in chapter 11: “Which is better…to have laws and agree, or to hunt and kill?” We all known what the desired answer is, but we also recognize the true identity of the beast, i.e. we are the beast. Ralph and Jack resemble each other in many ways, but they are also perfect opposites: Ralph opts for the correct road to follow, the one that attempts to retain a semblance of civilization. Jack, on the other hand, reverts to savagery. The potential is there for him to become the Enkidu to Ralph’s Gilgamesh, but Jack becomes Caliban instead.

I’ll not attempt to speak for others here in order to avoid a rush of denials, but I admit that deep inside of me is a dark place where I am envious of Jack when “He began to dance and his laughter became a bloodthirsty snarling." When is the last time you spent a night round a fire, preferably with paint on your face and ululating like a Big Bad Wolf? It can be an immense relief you see, to drop political correctness and polite etiquette and just put the gear in reverse by 10,000 years or so. Last time I did that, it was just me and friends around the fire. We had a couple of raw kilos of beef for dinner. No salad or vegetables, no plates or cutlery. Just a sharpened stick, a campfire and all that beef. Of course, such exercises are just a short mimicry of the real thing, a wee moment of make belief which Re-enactors call “Period Rush”, meaning you truly do forget that you’re living in the 21st century and have, for a brief moment, achieved some sort of time travel. Young kids do that continually by the way, they probably find it hard to believe adults have to go to a such great deal of trouble in order to achieve those moments.

Kids revert to savagery much easier as well, it is astonishing how many people think they’re nice little beings, cute even. They obviously never stuck a bunch of kids into a relatively small space, say a classroom, and waited around to see what happened. Kids are cruel, they’ll circle like wary predators and if a victim is found they’ll participate in a collective feeding frenzy of cruel taunts designed to wound. I think it is this that makes Lord of the Flies a good school book, kids recognize a lot of the stuff that is going on. One girl once told me she figured out why all the kids in the book were boys, “If they’d been girls, if there’d been 40 girls on that island without adults, why, we wouldn’t be able to read it in school anymore, it’d be hard core horror.”

If you ever read or watch Lord of the Flies with a bunch of kids still in their early adolescence pay close attention to the moment Simon and Piggy are killed. With Simon the reactions are mixed, and often delayed as it takes them a while to figure out that someone is actually being killed. Once it’s Piggy’s turn they’ve gotten used to the fact that Jack’s lot are into killing, and surprisingly few are actually rooting for poor Piggy, some even communicate the fact that they thought Piggy had it coming. Ask them why, and the answer is related to the fact that Piggy was different, he stood out from the crowd as it were. Burn the witch.

I find the innate savagery in the kids fascinating, at age eleven, twelve and thirteen they’re still coming out of a phase where reactions are purely primary, where they understand why Piggy is just as annoying as Brainy Smurf, forever lecturing about what Big Smurf (i.e. the adult) would think and do. Adults lecture them enough already, why thank you. In those rare moments when they’re not around to harass you, the last thing you want is some contemporary who clearly identifies himself with the enemy. Smashing his skull with a rock therefore, is understandable, possibly even a commendable action if it’s a story anyway. If the kid in question has already advanced beyond the primary reaction phase, usually because their parents had the sense to say “no” every once in a while and taught them to accept some facets of authority, then they’ll instinctively recognize that if we accept Piggy’s demise then someone else will be next as well as the fact that Ralph is the most likely candidate for the next witch hunt.

Regardless of our perspective, both adults and kids tend to be fascinated with primordial reactions and primitive interaction. We know it’s wrong, but read books about it, watch movies about it and possibly place ourselves into hypothetical situations where the wild beings deep inside of us come to the fore.

This is closely related to the almost universal male desire to go to war in order to discover how we conduct ourselves in battle, but not quite the same. The similarity is in the adrenalin. A creature of the wild is almost continuously in a situation wherein there is danger and therefore in a mental state in which there is an incredibly sharp and instinctual awareness of our surroundings. This is what happens when Thunderbirds are Go and that adrenalin takes charge. Being in mortal danger brings a wild exhilaration which is akin to both the experience of battle as well as being on a par with the existence of a savage living from moment to moment. Acting purely on instinct, say while engaged in one sport or another, is similar to this exhilaration as well. Since we’re no longer in a situation where we experience daily danger, we often seek it out in amusement parks or extreme sports and people can even become addicted to it.

The need to seek thrills is hardly surprising, considering the fact that virtual reality conveyed by computer, laptop and smartphone increasingly dominates our lives with artificial experiences. People are hungry for something genuine and real. Prime time then for literary savagery, which offers the appeal of simplicity, there being no morals to contemplate, no niceties to observe, no triplicate forms to be filled in and stamps of approval to collect. One, or so I imagine, simply is and simply does.

The longing for something real and genuine isn’t new, in 1904 Theodore Roosevelt makes mention of it in his Foreword to a new edition of Master of the Game, a book on hunting written between 1406 and 1413 by Edward Duke of York, grandson of King Edward III. Roosevelt mentions our cushy lives and the need to live rough every now and then. “The conditions of modern life are highly artificial, and too often tend to a softening of fibre, physical and moral. It is a good thing for a man to be forced to show self-reliance, resourcefulness in emergency, willingness to endure fatigue and hunger, and at need to face risk.”

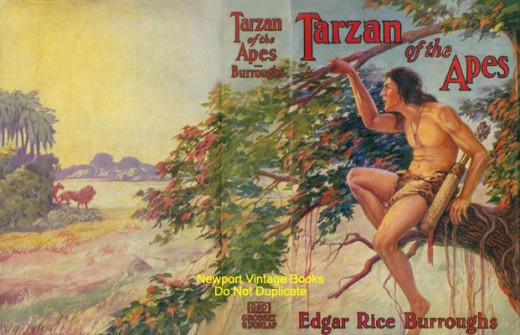

One person who took this advice to heart, presuming he read it, was Edgar Rice Burroughs, who published his first Tarzan story in 1912. Tarzan represents our opposite, he’s not a civilized man wanting to revert to savagery, but a savage needing to revert to civilization, something that he finds hard: “His civilization was at best but an outward veneer which he gladly peeled off with his uncomfortable European clothes whenever any reasonable pretext presented itself.”

One reason for Tarzan’s rejection of civilization is his dislike of it. “He hated the shams and the hypocrisies of it and with the clear vision of an unspoiled mind he had penetrated to the rotten core of the heart of the thing--the cowardly greed for peace and ease and the safe-guarding of property rights….In the clash of arms, in the battle for survival, amid hunger and death and danger…. in the display of Nature's most terrific forces, is born all that is finest and best in the human heart and mind."

So far it’s just a bit of personal philosophy by a man who can bang two brain cells together. However in the next part of this second chapter of Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar we glimpse the wild uncouth savage.

“He ate burnt flesh when he would have preferred it raw and unspoiled, and he brought down game with arrow or spear when he would far rather have leaped upon it from ambush and sunk his strong teeth in its jugular….he craved the hot blood of a fresh kill and his muscles yearned to pit themselves against the savage jungle in the battle for existence that had been his sole birth right for the first twenty years of his life."

Note Burrough’s use of the word “veneer”, he liked to use the phrase “the thin veneer of civilization” in his Tarzan books in order to remind us that man isn’t all that far removed from the primitive within us.

Someone else with an interest in that thin veneer of civilization was Jack London, who published an essay called “The Somnambulists” on June 13, 1906.

"Civilization…. has spread a veneer over the surface of the soft shelled animal known as man. It is a very thin veneer; but so wonderfully is man constituted that he squirms on his bit of achievement and believes he is garbed in armor-plate. Yet man to-day is the same man that drank from his enemy's skull in the dark German forests, that sacked cities, and stole his women from neighboring clans …. The flesh-and-blood body of man has not changed in the last several thousand years. Nor has his mind changed. There is no faculty of the mind of man to-day that did not exist in the minds of the men of long ago….It is the same old animal man, smeared over, it is true, with a veneer, thin and magical, that makes him dream drunken dreams of self-exaltation.”

How to reduce these dreams of self-exaltation?

“Starve him, let him miss six meals, and see gape through the veneer the hungry maw of the animal beneath. Get between him and the female of his kind upon whom his mating instinct is bent, and see his eyes blaze like an angry cat's, hear in his throat the scream of wild stallions, and watch his fists clench like an orang-outan's. Maybe he will even beat his chest.”

When I cover this theme I usually allow the students to design an idealistic week with no adults telling them what to do, i.e. no parents, grandparents, teachers, coaches, bus drivers, shopkeepers etc. Ah ça ira, ça ira, ça ira, Les aristocrates à la lantern! Up the Revolution! They embark on this assignment gleefully but it never takes them very long to figure out things would fall apart very quickly and that they too would revert to a savagery that becomes a lot less appealing if and when you land in the midst of it.

Now go away, I’ve got a few vines to swing on and lions to wrestle.

(copy and paste onto another screen: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MwHWbsvgQUE)