George Orwell's 1984: A Prophecy Come True

In part three, chapter three of this world-conquering book, the villain, the sinister Party strongman named O'Brien, informs Winston Smith, the protagonist, of the Party's ultimate goal:

“We shall abolish the orgasm. Our neurologists are at work upon it now.”

“If you want a picture of the future,” says O'Brien later, “imagine a boot stamping on a human face—forever.”

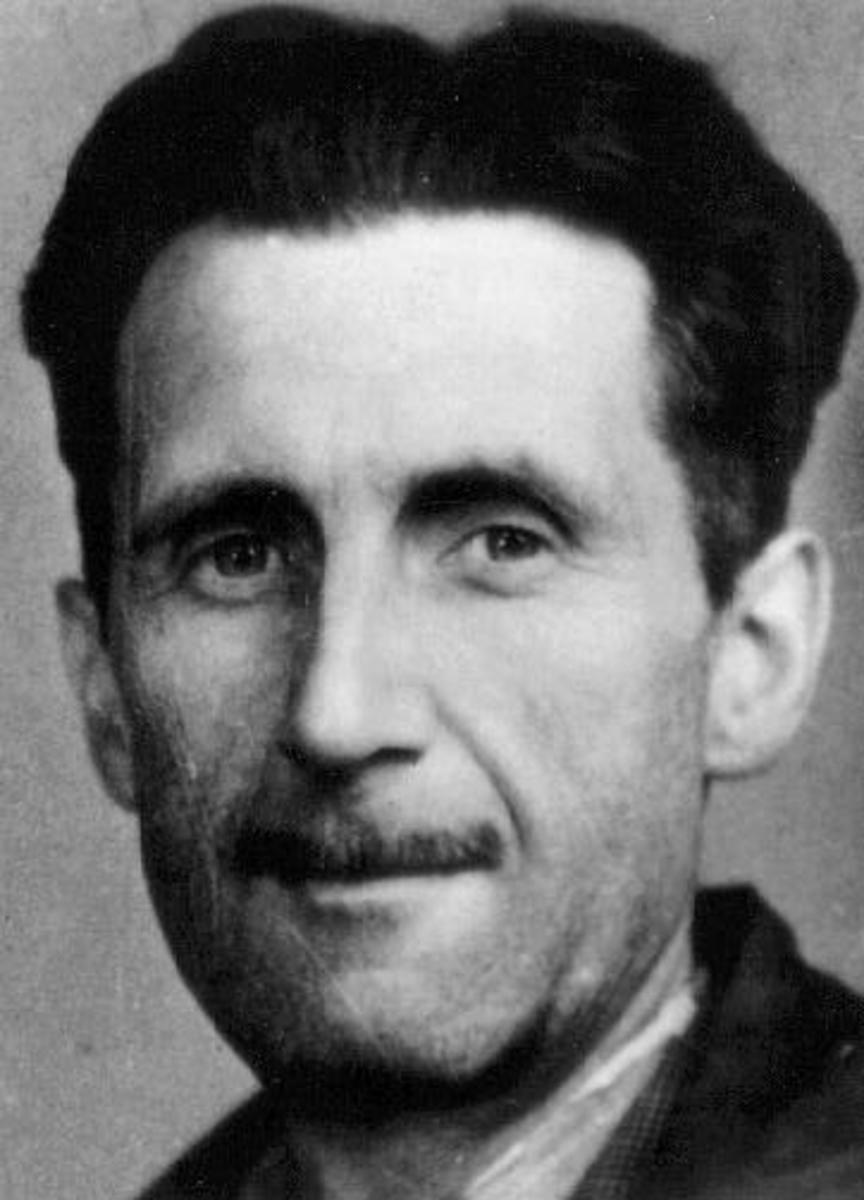

Here we see an example of both the humor and absurdity of the Indian-born Englishman Eric Arthur Blair, who wrote under the pen name George Orwell. It's through this dark and subtly impassioned vision of totalitarianism that Blair/Orwell captured the admiration of posterity with the final work of his imagination.

Written in 1947 and 1948 during the terminal months of Orwell’s tuberculosis at a remote cottage on the Scottish island of Jura, 1984 is said to have derived its title from the inversion of “48”, the year of its completion, to “84”.

It wasn’t a particular year that Orwell was trying to describe: merely a time not all that far in the future, though a time which he knew he would not live to see himself. A better title for it might have been "2015."

I think the humor of 1984 is more underappreciated than in any other well-known literary work. For this novel is, first and foremost, as Orwell himself called it, a parody.

For sure, it is not the sort of humor at which we laugh outwardly; it is instead a constant black humor, purveyed in the same spirit as Orwell’s previous work, Animal Farm, a beast fable about the Russian revolution.

The clinical, dry, precise nature of Orwell's prose, and the bleak backdrop of the world he is describing, perfectly suit his ultimate intent.

Total state control of information, torture of unorthodoxy, demagoguery and perversion of language for political reasons, wanton murder and abuse of heresies by those in power, mass hysteria from perpetual worldwide warfare—these were elements of the recent past at the time 1984 was written.

It was Orwell’s attempt to extrapolate the future from what had already happened, and to imagine how much worse a society might be in the future if trends continued to drift in their current direction, that led to his most famous book.

Plot Summary

Winston Smith, a frustrated bureaucrat on Airstrip One, a province of a fascist futuristic society called Oceania, is employed in the Ministry of Truth. His job is to change historical records which conflict with the ideology of the Inner Party, a mysterious group of elite rulers who are publicly personified by a mythical image called Big Brother.

Confined to a meager one-bedroom apartment in London, Winston is limited in his thoughts and movements by the Thought Police, who supervise him on telescreens in every nook of his living quarters.

When Julia, a young coworker who operates novel-writing machines at the Ministry of Truth, hands him a secret note telling him she loves him, the two of them arrange to consummate an affair at a rendezvous far out in the countryside.

Because of the constant surveillance of all activities through telescreens, Winston and Julia must watch what they say and where they are seen. They also must continue to follow the Party’s prescribed rules for behavior, participating in monstrous mass demonstrations called “Hate Week” and the “Two Minutes Hate”. Occasionally this means shifting allegiance immediately when the Inner Party suddenly decides to change alliances during wartime.

It is also necessary to adhere to the rules of a special language called Newspeak, in which words that have specific meanings are destroyed and words that are vague and general are preserved.

Eventually, Winston and Julia arrange to rent an old room above an antiques store in a rundown neighborhood in London. In the meantime, Winston is approached by an Inner Party member named O’Brien, who deceives him into thinking he is part of a secret society named the Brotherhood whose goal is to overthrow Big Brother.

O’Brien lures Winston into revealing several personal heresies and ultimately tracks him down in his bedroom with Julia, alerted to the tryst by the antiques dealer landlord who is actually a Party spy.

Winston and Julia are arrested and sentenced to the Ministry of Truth, where they are tortured separately. While he waits, Winston witnesses the abuse of political prisoners with bludgeons, truncheons, jackboots, syringes and racks.

He himself is delivered to brainwashing sessions in Room 101 at the basement of the Ministry of Truth, where O’Brien interrogates him, subjects him to electrical shock and threatens him with a cage full of hungry rats. He finally betrays Julia, reveals all of their secrets, and professes his undying love for Big Brother.

Released from torture, Winston returns to his old life in Oceania, his brain numbed by Victory Gin and his emotions warped by Party propaganda. He sees Julia in a town square and she informs him that she also betrayed him during torture. They part for the last time and Winston feels an upsurge of love for Big Brother when he sees a large painting of him.

Assessment

The urgency of death, which came to the real-life Eric Blair in 1950, about a year after the publication of 1984, seems to have inspired him, in the name of his alter-ego George Orwell, to heights of creativity and rhetorical power that he had never reached previously.

There is perhaps no other work that I've read in which an author more perfectly realized his intentions than 1984 and more successfully used every literary and intellectual device of which he was capable.

It is, in that sense, a consummate work of art. Orwell said if he could preserve six books among all others he would choose Gulliver's Travels as one of them. I would go further in praising his own book. If I myself were allowed to choose a single book among all others I might take with me to a realm that had no other books, I would select 1984.

For in this twisted fantasy world we have the renunciation of humanity, an imaginary society’s complete suppression of all that gives value to our lives: love, compassion, generosity, curiosity, meaningful words, and the freedom to seek truth and express its discovery. The author has illustrated the necessity of these virtues by showing us a world in which they are all made illegal.

In many respects the future has not improved the conditions which bothered Orwell and inspired him to compose this dire fable.

While it is true that the Soviet empire has collapsed, China has become a champion of capitalism, and one hard-line despot after another in Eastern Europe and Latin America has been toppled, Big Brother has not in any way disappeared.

In our time every routine transaction—whether by credit card, cell phone, or internet—is tracked. Cameras in public places and along highways record our movements. The state is omnipresent in ways that far exceed anything Orwell himself imagined. We are all being watched.

Any slip-up of any sort, any expression of “unorthodoxy” (for isn’t the concept of political correctness just another name for orthodoxy?) carries with it swift, harsh and sometimes life-destroying retribution. Freedom of speech? Where is it now? Freedom of expression? On whose terms?

News headlines which now feature policemen murdering civilians—and these are common—are simply the realization of Orwell’s apocalyptic vision of a state which monitors every step and every movement of all its citizens, and exacts sometimes cruel and arbitrary punishment on those who resist it.

“Security” is simply a code word for “surveillance”. The bugaboo of terrorism is simply the “Two Minutes Hate” of our time: the spectacle used by Big Brother to soften our resistance to ever-increasing scrutiny of our private activities, expressions and behaviors.

In this sense, the dying man’s legacy to us is something about which we continue to be indifferent and passively acquiescent. If we don’t want Big Brother to keep watching us we must do something about it. Who is really in charge of whom? It may already be too late for us to correct the imbalance.

© 2015 James Crawford