- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Literature»

- Literary Criticism & Theory

Representing the Real: the Narrative Construction of Reality in Duras and Didion

How can real life, with its chaos and randomness ever be presented as a story – a narrative with a beginning and an end, one that has meaning and significance and one that needs to be told? What elevates an account of a sequence of events beyond simple reportage into a story worth telling?

The Year of Magical Thinking and The Lover, despite their different allegiances to the truth signified by their different genres, both achieve this difficult feat. These two texts give us an insight into how accomplished writers approach the subject of constructing a story from their own lives.

Didion, steeped in the tradition of non-fiction, and Duras, coming from the world of fiction and positioning The Lover in the shifting sands between fact and fiction, both have the same brushes in their tool box. How they use these brushes to apply paint to the canvas is what makes the two pieces so different to each other.

Photography is a simple and direct means of turning what is real into an artistic representation. I will attempt to use photography as a metaphor for the autobiographical process.

In photography there are three techniques employed in transforming a snap shot into a work of art – framing, depth of field and point of view. In creating a textual representation of real life, three modes of writing are also required – seeing, understanding and evaluating.

Jerome Bruner [The Autobiographical Process, 1995] calls seeing – the discourse of witness, understanding – the discourse of interpreting and evaluating – stance which ‘is the autobiographer’s posture towards the world, toward self, toward fate and the possible, and also toward interpretation itself’.

I would like to begin with the third idea – stance – because it is the one I am least familiar with and the one I believe should be the starting point in any kind of writing.

STANCE – Towards Self

Unfortunately, my photography analogy falters at the first hurdle because I believe that the notion of a writer’s stance towards oneself is the most difficult to pin down when talking about autobiography.

In fiction, it seems easier to separate the writer, the narrator and the protagonist and readers understand that these three constructs are not always the same thing. The author is distinct from the narrator, and the narrator is not always the protagonist (like Nick in the Great Gatsby).

But when writers write about real lives, the lines between author, narrator and protagonist can become smudged and indistinct.

Bruner [Alfred Korzybski Memorial Lecture, 1988] explains:

‘There is a narrator, here and now, who is holding the pen or speaking. He is telling a story about a protagonist who happens to bear the same name as his. He, the narrator, is telling the story here and now about a protagonist who lived there and then under different circumstance. In the end, his task as an autobiographer is to bring the narrator and the protagonists into each other’s arms in the present.’ [my emphasis]

What is Didion and Duras’ stance towards their identity? Do they identify themselves primarily in terms of age, gender, race, class, occupation or something else? Is there a narrator in the here and now and a protagonist from the past?

In The Year of Magical Thinking it is difficult to find much about Didion explicitly on the page. In this work the narrator identifies herself as a widow and a mother. The protagonist from the past, from before the death of her husband, was a wife and a writer. She seems to be trying to reconcile these two separate selves.

Duras’ narrator in The Lover is a woman in old age, ravaged by time and by alcoholism. Her protagonist is fifteen and a half, first and foremost. Beyond that, she is a student, a daughter, a sister and the lover of a much older man. Duras often refers to her protagonist, her younger self, in the third person, increasing the distance between her past and present selves.

The loose connection between literary stance towards the self and photography occurs when an artist takes a self-portrait.

These two photographs of the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe show the different ways he sees himself. Neither of these pictures is able to depict the full and complex nuances of Mapplethorpe’s personality – in the same way that the ‘I’ in autobiographical writing can never be a full representation of the author.

STANCE – Towards the World

The photographer’s point of view is the position from which he views his subject.

This photograph is taken at ground level and emphasizes the uneven floor and the legs and feet of the person.

In this photograph of the same place, the woman is seen almost trying to escape the walls, the floor and the shadows in the room.

Autobiographers assume a posture towards the world. This could be understood as the theme of the work or perhaps an argument. Marion Roche Smith, in her book The Memoir Project, suggests every good life narrative must have a universal argument which is illustrated by a specific story.

Her formula is ~ This story argues X, illustrated by Y, to be told in Z.

Let's try Smith’s formula for The Year of Magical Thinking:

This story argues that you cannot deal with grief coolly or even sanely, as illustrated by the death of the protagonist’s husband, to be told in a memoir.

And for The Lover:

This story argues that even a young girl can possess sexual power, as illustrated by protagonist‘s illicit love affair with an older man, to be told in a fictional autobiography.

My reading of the argument or theme of these two texts will be different to another person’s and probably different to what the author intended. But when an author undertakes the task of representing real life, he or she assumes a posture towards the world.

It might be as simple and banal as 'Life is better with a cat.' And yet one of the most moving memoirs I've read was based on that very argument. Cleo by Helen Brown, tells how a new kitten, the narrator reluctantly bought for her son just days before he was killed in a traffic accident, helps her get through her grief.

Formulating an argument rather than simply coming up with a theme can be helpful. When writing a scene, one can ask ‘How do these events prove or disprove my argument?’ which leads us to the next facet of autobiographical writing – the discourse of witness.

WITNESS

Autobiographical writing involves accounts of happenings in which the narrator participated, if only as an observer.

These accounts are a product of creation rather than merely reporting. A writer creates through the process of selecting which events he or she writes about.

Judith Fishman [Enclosures: The Narrative within Autobiography, 1981] describes it as: ‘the narrative line is a way of centring, of holding things together, of selecting out of randomness; it is a forming, a shaping, a necessary means of making sense of it all.’

William James [The principles of psychology, 1893] uses the term ‘selective attention’ which is selecting out of the myriad of things that happen to us, events, objects and details that we pay attention to, to the exclusion of others.

In photography, this is called framing. The photographer decides what will and won’t be in the frame.

![This is the cropped photo by Weegee: ‘The Fashionable People, [title first used for "The Critic" in LIFE Magazine], published December 6, 1943. This is the cropped photo by Weegee: ‘The Fashionable People, [title first used for "The Critic" in LIFE Magazine], published December 6, 1943.](https://usercontent1.hubstatic.com/9222496.jpg)

It could be argued that the second picture tells more of a story than the first, provides context and a sense of juxtaposition. I am not advocating that less is inherently better, in fact, as a writer who struggles with conciseness; it is a good reminder that often the opposite is true. It is in the spaces around our subject that things sometimes happen.

Bruner reminds us: ‘We are not autonomous, self-contained atoms. We live for and with others. […] We cannot reflect upon the self without an accompanying reflection on the nature of the world in which one exists.’

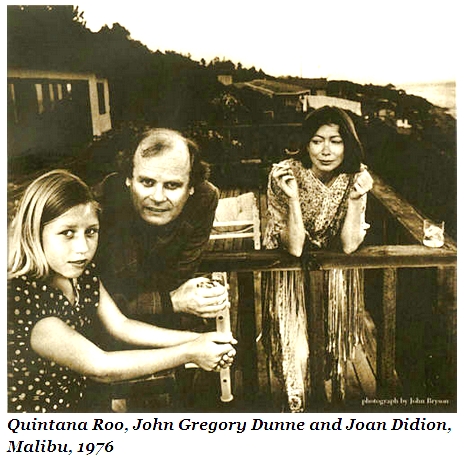

Didion frames her narrative by selecting from her life only the events that relate to her husband and child.

She writes:

‘Quintana was admitted to the ICU at Beth Israel North on December 25, 2003.

John died on December 30, 2003.

I told Quintana that he was dead late on the morning of January 15, 2004, in the ICU at Beth Israel North, after the doctors had managed to remove the breathing tube and reduce sedation to a point at which she could gradually wake up.’

Didion’s memoir is full of this cool, distant recounting of facts couched in the language of medicine. The narrator wants to believe that information is control. And yet despite all this gathering of knowledge the narrator still finds herself in a state of magical thinking.

The relationship between mother and daughter is one of the frames Duras uses in her narrative – perhaps the most important one. It reminds me of Duras’ stance on madness and neurosis. She believes they are positive forces because they suggest closeness to nature and to the self that shuns useless theories, empty facts and irrelevant knowledge. According to her, ‘all women are neurotic, so in touch with themselves that they know intuitively what they want. And yet some women […] accept male standards and emulate men; by refusing their own intelligence, they deny their own nature.’ [Husserl-Kapit & Duras. An Interview with Marguerite Duras, 1975]

Perhaps The Lover isn’t about sexually it all – maybe it is more about the nature of women’s neurosis and how it makes them behave.

Duras writes:

‘It’s there, in that last house, the one on the Loire, when she finally gives up her ceaseless to-ing and fro-ing, that I see the madness clearly for the first time. I see my mother is clearly mad. I see that Dô and my brother have always had access to that madness. But that I, no, I’ve never seen it before. Never seen my mother in the state of being mad. Which she was. From birth. In the blood. She wasn’t ill with it, for her it was like health, flanked by Dô and her eldest son. No one else but they realised.’

But unlike Didion who is a dispassionate observer, Duras interprets everything she experiences. It is the amount of the discourse of witness in proportion to the discourse of interpretation that makes these two texts so different.

INTERPRETATION

Depth of field is the selective sharpening of an element in a photograph in order to examine it more closely. This is the photographic metaphor for Bruner’s witness of interpretation. ‘A good autobiography,’ he says, ‘transcends issues of what actually happened and deals with meaning.’

How much depth of field is in The Year of Magical Thinking? The answer is not enough for me. One reader’s review on Amazon sums up how I feel.

‘The endless facts, medical explanations, and most of all, Joan's continuous detachment from any emotion, left me feeling beat up and worn down. Yes, it even annoyed me a little. I give her all the credit in the world for approaching her task. The Year of Magical Thinking is written in the first person, but not for a split second do we get a glimpse of any sensitivity coming from her. She only looks, thinks, and writes. But who is Joan, and what is going on inside her? Anything at all?’

And in The Lover? Perhaps too much for some tastes. Her list of events is short, her narrative line thin, but she surrounds everything with so much reflection about family, death, beauty, aging, eroticism, and the physical landscape of Indochina that the reader hardly notices not much happens.

The following simple narrative autobiographical text summarises the ideas of witness, interpretation and stance.

1 I was born in the Midlands. My family ran a hotel.

2 The obstetrician when I was born picked me up by my heels.

3 He slapped me on my back.

4 He broke two ribs.

5 You see I had osteoporosis.

6 That’s the story of my life.

7 People trying to do good for me ending up by breaking my bones.

Line 1 is the writer’s stance towards his identity – his or her self-portrait.

Lines 2-4 is the account of events, the frame, the discourse of witness.

Line 5 is the writer’s interpretation or the depth of field. Without this sentence, the reader has no way of knowing why the protagonists’ ribs were broken.

Line 6 and 7 tells the reader of the narrator’s point of view, his argument, his stance.

In just seven lines, the reader understands …

- What happened to the protagonist (witness)

- What it meant to the protagonist (interpretation)

- And what the narrator learnt about himself and about the world (stance)

Three important things to remember when we write about our lives.