The Brothers Karamazov: A Study in Guilt

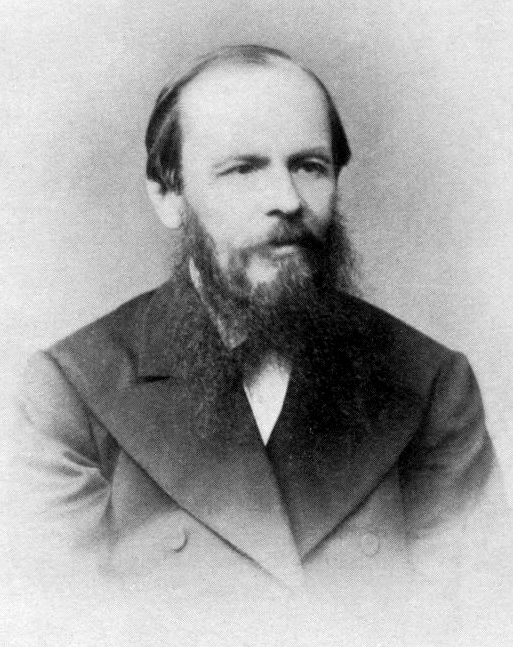

Albert Einstein once remarked that the most influential thinker in his development was not a fellow physicist or even a fellow scientist, but a Russian novelist, Fyodor Dostoevsky. Albert Camus, another Nobel laureate of the 20th century, proclaimed that his century’s foremost prophet was not Karl Marx, but Dostoevsky. Joseph Stalin, in a startling admission of pre-revolutionary awareness, claimed to have read Dostoevsky’s final work, the sprawling epic Brothers Karamazov (pronounced (Kara-MAH-zoff), multiple times. Sigmund Freud stated that this book was “the most magnificent novel ever written.” Pope Benedict made reference to the novel during his papacy in 2007.

Present-day Americans are likely to know little about either Dostoevsky or Karamazov. At times overshadowed in popular culture outside of Russia by his younger contemporary, Count Leo Tolstoy, whose War and Peace and Anna Karenina have repeatedly been adapted by Hollywood, the deeper-thinking and more tortured Dostoevsky is a vague and shadowy figure to the average Westerner of our time. We’ve heard his name and somehow associate his writings with guilt and crime, but few of us can explain why Einstein, Freud and others prized his work above all others.

In order to understand Dostoevsky we must consider his background and many of the extraordinary experiences of his life. Unlike Tolstoy, a hereditary aristocrat, Dostoevsky was born into a bourgeois family and struggled with debt and poverty for most of his adult life. Born in Moscow in 1821, young Fyodor had literary aspirations and moved to St. Petersburg, then the capital and creative center of Russia, during his university years.

His father’s premature death when Dostoevski was 18, never entirely explained, may have been the result of murder by one of the family’s servants. The mystery of this tragic loss haunted Fyodor and colored much of his adult sensibilities.

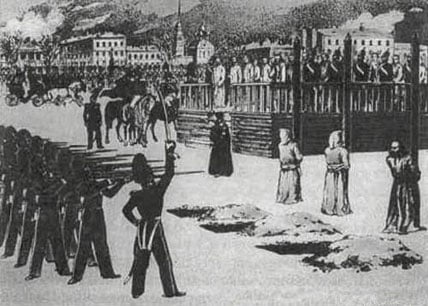

His first novel, Poor Folk (1845), a story of the social conflicts of two poor female cousins, won him acclaim within Petersburg society and inflated his ego. But he ran afoul of the Tsarist regime when he joined the Petrashevsky Circle, a secret society of intellectuals that had pro-Western liberal-leaning tendencies. Arrested by the secret police of Tsar Nicolas I, Dostoevsky and several of his literary colleagues were accused of treason and sentenced to be shot before a firing squad two days before Christmas of 1849.

In the last hour, as he was being carted to the place of execution, Dostoevsky and his friends were given a reprieve by the Tsar. Instead of the death sentence, their punishment was commuted to eight years of forced labor in Siberia. A dramatic scare tactic, perhaps? No one knows for sure what prompted Nicolas to spare the young man who later became one of the creative icons of his nation, but the death sentence was never carried out.

Humbled after serving his sentence in Siberia, plus an additional two years in the military, Dostoevsky returned to St. Petersburg, where an unhappy marriage to Maria Isaeva and stubborn pride led to an itinerant existence. He had continual bouts with epilepsy, several casual affairs, fled Russia to travel in Europe, ran up large gambling debts, and struggled to achieve financial stability despite the success of such novels as Notes from Underground (1864), and Crime and Punishment (1866).

After Maria’s death in 1864 he met Anna Snitkina, whose steady support and encouragement as his second wife led to the relative prosperity of his later years. It was only during the last decade of his life that he rose to full acceptance within both the Orthodox church and the Tsar’s political establishment and enjoyed a period of happiness despite his son Alyosha’s tragic death of epilepsy in 1878. The same illness led to a series of pulmonary hemorrhages which cost him his own life in 1881 after completion of The Brothers Karamazov.

The recurring pattern of Dostoevsky’s own personal life was one which he often repeated in the lives of his fictional heroes: pride followed by a criminal act leading to punishment, shame and ultimate contrition, redemption and forgiveness. This motif is most fully realized in his final and most mature work.

Summary

Fyodor Karamazov, a petty landowner from a provincial town somewhere between St. Petersburg and Moscow, is known for his womanizing and shiftless behavior. He has outlasted his first two wives, who died of illness, and continually vies for ever-younger and prettier mistresses.

One of the young damsels who has caught his attention, Agrafena Svetlova (Grushenka), also happens to be beloved by Dmitri (Mitya), his only son by his first wife. Mitya is a profane and violent-tempered bon vivant who is nevertheless engaged to yet another woman, Katerina Verkhovtseva (Katya). The two men often fight and quarrel, buffered by the two sons of Fyodor’s second marriage: Ivan (Vanya), a nihilistic atheist, and Alexei (Alyosha), his youngest, a devout soul of noble character and good heart.

Alyosha, perhaps swayed by the profligacy and debauchery of his father and two older brothers, has a religious yearning. He is much beloved of the town’s foremost cleric, the Orthodox monk Zosima, in whose hermitage Alyosha frequently seeks refuge. Encouraged by Zosima, Alyosha has resolved to take monastic orders himself and renounce the sins of the world.

However, he is continually drawn into his family’s bitter infighting. Fyodor, perhaps seeking to solidify his moral authority over his eldest son, asks Zosima to arbitrate a family dispute in his monastery, but instead of reconciling in the monastery, Fyodor and Mitya come to physical blows and Mitya threatens to kill him.

Vanya, the second son, has a festering hatred for his father’s vulgarity and laziness and sympathizes with Mitya’s violent grudges. While Mitya loves and respects his younger brother, Vanya mistrusts his piety, though he also eventually develops a grudging respect for him.

Fyodor’s designs on young Grushenka seem partly aimed at cheating Mitya and Ivan out of their anticipated share in his estate. Tempers in the two older sons continue to build and they both openly anticipate their father’s ultimate murder. Alyosha, under the tutelage of Zosima, is unable to persuade them to adopt Christian forbearance and is left utterly helpless after Zosima’s death of old age.

During an earlier act of drunken sexual assault upon an uncouth homeless orphan named Lizaveta, Fyodor is rumored to have fathered another son named Pavel Smerdyakov. After Lizaveta dies in childbirth her son grows up as a Karamazov family servant without ever hearing acknowledgment of Fyodor’s paternity. Smerdyakov, a cynical, scheming and bitter character, frequently argues with all three of the Karamazov brothers, though maintaining the perfect attitude of a faithful servant toward Fyodor.

The occasion finally comes for Mitya to carry out his planned murder of his father. He desperately needs to repay a 3000-ruble debt which he owes to Katya, his fiancée, and plans to steal the funds from his father’s room after murdering him.

He grabs a pestle from a nearby shop, climbs to his father’s window late at night, bludgeons a servant named Grigory and intends to murder his father and take the money, though the actual act of murder is never described. Mitya flees to a nearby town to join Grushenka but is quickly tracked down and arrested by the police.

The date of trial approaches and the overwhelming circumstantial evidence seems to point to an inevitable murder conviction for Mitya and a sentence of 20 years forced labor in Siberia. But Mitya insists on his innocence. He admits to having assaulted Grigory, who survived his injuries, but not to the murder of his father. Ivan and Alyosha both support their brother and swear to his innocence.

As a last-ditch effort, Ivan arranges for a meeting with Smerdyakov and extracts a shocking confession: Smerdyakov admits to having actually committed the murder after Mitya fled without mustering the nerve to do it himself. Just before the date of the final trial, Smerdyakov hangs himself and Ivan’s claim is dismissed by the judge, who, despite a spirited defense effort by renowned Petersburg attorney Fetyukovich, condemns Mitya to Siberia.

The emotional toll of the trial has weakened Ivan, and he collapses with an evident terminal fever. Alyosha begins plotting for Mitya and Grushenka to escape to America, where they hope to learn English and become naturalized citizens. Alyosha is left as the moral and spiritual head of the Karamazovs, seeking to rectify the wrongs of his father and brothers, and to make amends at the funeral of Ilyusha, a young schoolboy whose father Mitya had once publicly insulted.

Assessment

The Brothers Karamazov was originally serialized in the periodical The Russian Messenger between January of 1879 and December of 1880. In the 19th century this was a common method of publication for many novelists. Charles Dickens and Mark Twain, among several others, wrote much of their work in installments.

While this had the beneficial effect, to the modern reader, of requiring a cliffhanger of sorts at the end of every installment it also encouraged long-windedness. Writers were paid by the word. They were obliged to extend their story to cover the required number of units in the series. This was commercially advantageous to Dostoevsky and others, but it artistically weakened the novels for later generations.

In Dostoevsky’s day, readers throughout Russia were thrown into fits of suspense by the interruptions in the series. How could anyone other than Mitya have done the murder? Why did Alyosha, a man of unblemished integrity, continue to insist on his brother’s innocence? If Mitya wasn’t the murderer, who was?

These and other questions stimulated controversy and sales. But today, with the book in its entirety from cover to cover, the many sidetracks, digressions and long philosophical dissertations which are outside the central plotting of the story considerably weaken its force.

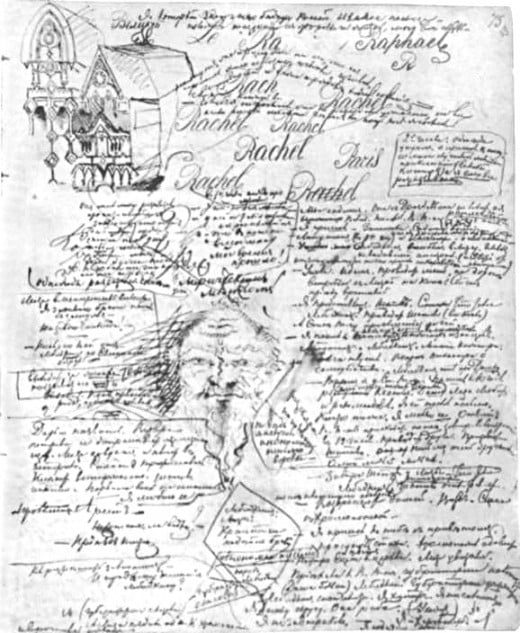

Of course part of the problem may be that the original spirit of the work in its native language is lost in translation. I read the 1990 translation by Pevear and Volokhonsky, which, though acclaimed as the best English version of the work to date, can never equal what Dostoevsky actually wrote in the original Russian.

I admit that any translation of a work from its native language into a different one is a little like a broken dish glued back together. No matter how skillfully the parts are put back together the cracks will always be visible and the glued-together repair can never match the whole original dish.

But I still firmly believe that if the novel were about a third its present length it would be far more effective at conveying to a reader of today its basic themes, which are the essence of the Dostoevskian cycle of personality: pride and arrogance lead to violence and crime, whether mental or physical, which must be punished in order to produce repentance and allow room for redemption.

And underneath this is the cumulative effect of emotional torture on the human soul: the guilt of Mitya, the godlessness of Ivan, the sense of abandonment and inferiority in Smerdyakov. The sins of the father ultimately fall to the son, and the son in his life must make amends for the inherited guilt of his ancestry.

These are the themes, I think, which won Dostoevsky his enthusiastic following among intellectuals who came after him. For as long as people live in families, these will be enduring themes to which succeeding generations will turn to Dostoevsky as the master.

© 2015 James Crawford