- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Literature»

- English Literature

"The Church’s Social Responsibility" in Charles Dickens’s Bleak House (Part 2)

Bleak House

The Telescopic Philanthropist

Most Responsible

Who was most responsible for Mrs. Jellyby's errant behavior?

"Missionaries": Methods and Effectiveness

Mrs. Jellyby

Bleak House’s fourth chapter “Telescopic Philanthropy’” satirizes Mrs. Jellyby’s obsession with Africa, and rightly so. In reply to Esther’s inquiry as to the identity of Mrs. Jellyby, Mr. Kenge describes an individual wholly dedicated to a mission of dubious merit:

Mrs. Jellyby is a lady of very remarkable strength of character, who devotes herself entirely to the public. She has dedicated herself to an extensive variety of public subjects, at various times, and is at present (until something else attracts her) energized about the subject of Africa; with a view to the general cultivation of the coffee berry—and the natives—and the happy settlement on the banks of the African rivers, of our superabundant home population (Dickens 49-50).

The text does not mention Mrs. Jellyby’s sponsor, but some group must have influenced her to undertake her foreign philanthropy. It was, in all likelihood, her local Anglican assembly, but she might have read about “Borrioboola-Gha on the left bank of the Niger” elsewhere. Perhaps she heard loquacious Mr. Quale, another philanthropist, mention the topic when he discussed the “Brotherhood of Humanity” with her (58).3 No one seemed to have motivated her beyond the means discussed above, so she might have been an individual foot soldier off on her own mission.

The text also does not indicate whether or not Borrioboola-Gha missionaries preached the gospel; however, Tarr’s words suggest that some Christianization may have been taking place: “Missionaries, like Mrs. Jellyby, summarily ignored the waifs around them in their avidity to advance the stature of the African under the guise of Christianity and humanitarianism” (276).

What might account for Mrs. Jellyby’s errant judgment? Certainly one factor was her husband. His passive nature not only made him impotent as a family leader, but also miserable as a human being:

During the whole evening, Mr. Jellyby sat in a corner with his head against the wall, as if he were subject to low spirits. It seemed that he had several times opened his mouth when alone with Richard, after dinner, as if he had something on his mind; but had always shut it again, to Richard’s extreme confusion, without saying anything (57).

Without a husband able to help her make decisions beneficial to the family, Mrs. Jellyby spent an inordinate amount of time and effort trying to advance the African project, involving her poor daughter Caddy in the tedious labor, and horribly neglected to take care of her home and children. Esther gives the reader a glimpse of the Jellyby household:

The room, which was strewn with papers and nearly filled by a great writing-table covered with similar litter, was, I must say, not only very untidy, but very dirty. We were obliged to take notice of that with our sense of sight, even while, with our sense of hearing, we followed the poor child who had tumbled downstairs: I think into the back kitchen, where somebody seemed to stifle him.

But what principally struck us was a jaded, and unhealthy-looking, though by no means plain girl, at the writing-table, who sat biting the feather of her pen, and staring at us. I suppose nobody ever was in such a state of ink (53).

Perhaps Dickens rightly lambastes Mrs. Jellyby, but the real culprits are the recognized leaders in her family and her church, who should have made every effort to persuade her to “involve the devotion of all my energies, such as they are” toward those in her neighborhood (53).

Thus Mrs. Jellyby fails to measure up to Dickens’s ideal on at least two accounts: (1) She supported a foreign missionary outreach that might have been preaching Christian doctrine to African natives; and (2) she neglected not only her family, but also those indigent ones nearby, like Jo, who might have survived had he received her help.

Dickens’s concern for his country’s needy is admirable; but with all his compassion, I believe that he fails to take into account that man has an immortal dimension, too. Mrs. Jellyby’s problem was not that she cared for foreigners, but that she lacked the guidance that would have provided balance to her life. If she had acknowledged her primary responsibility to “hearth and home,” she still could have involved herself with foreign missions, albeit on a smaller scale. Let’s move on to a compatriot of Mrs. Jellyby: Mrs. Pardiggle.

Fair and Balanced?

Do you think Dickens fairly characterizes people who favor foreign missions?

Mrs. Pardiggle

Dickens truly makes Mrs. Pardiggle a pitiful, even contemptible woman, certainly one who would “change the direction of the wind” for Mr. Jarndyce (124). Her passion for work—gauged by the amount of time she spends and the level of sacrifice she endures on a multitude of services to which she also makes her children tag along—exudes from the pages of the novel without a hint of humility:

They attend Matins with me (very prettily done), at half-past six o’clock in

the morning all the year round, including of course the depth of winter, . . . and they are with me during the revolving duties of the day. I am a School lady, I am a Vistiing lady, I am a Reading lady, I am a Distributing lady; I am on the local Linen Box Committee, and many general Committees; and my canvassing alone is very extensive—perhaps no one’s more so (Dickens 125-126).

She is surely not a model of Catholicism simply for her many works, since her manner in performing these activities manifests a lack of love for people, especially her children.

True compassion—a primary characteristic of a Godly, lay missionary—is completely lacking in her character. Her visit to the brickmaker’s home finds her demeanor pompous, overbearing, and uncaring. Surrounded by filth, degradation, and abuse, she could only think about her own faithfulness and ability to endure hard work. Esther gives us a view of her abrasiveness:

Well, my friends, said Mrs. Pardiggle; but her voice had not a friendly

sound, I thought; it was much too business-like and systematic. How do

you all do, all of you? I am here again. I told you, you couldn’t tire me, you know. I am fond of hard work, and am true to my word (131).

Dickens despised religious people who worked hard, but did not care for others. Thompson writes, “Mrs. Pardiggle fails because ‘her voice had not a friendly sound . . . it was much too business-like’ –in other words, there was no love or genuine sympathy, and to Dickens these qualities were far more important than dogma or mere activity” (39).

But not only does Mrs. Pardiggle fail in her domestic mission work, she imitates Mrs. Jellyby by unwisely pouring finances into a project to relieve the plight of a foreign people. Her work to aid the Tockahoopo Indians of America is her great love, but “in her rapacious benevolence for the Tockahoopo [. . .], Mrs. Pardiggle persevered over her family to the extent of impounding the whole of her children’s allowances in order to add to her subscription list” (Tarr 278). She completely neglects her children’s welfare and enjoyment for the sake of those she did not know. Esther reports the horrible visages of the Pardiggle kids:

We had never seen such dissatisfied children. It was not merely that they were weazen and shrivelled—though they were certainly that too—but they looked absolutely ferocious with discontent. At the mention of the Tockahoopo Indians, I could really have supposed Egbert to be one of the most baleful members of that tribe, he gave me such a savage frown. The face of each child, as the amount of the contribution was mentioned, darkened in a peculiarly vindictive manner, but his was by far the worst (Dickens 125).

Again, this portrayal is probably not a fair representation of the typical, church-going Catholic worker of the nineteenth century. Dickens created this caricature because he wanted to communicate the wrong-headedness of devoting oneself to foreign missions.

Like Mrs. Jellyby, Mrs. Pardiggle does not measure up to Dickens’s ideal either. She labors exceedingly in her local missionary activity, but spoils it with her loveless manner. Robbing her children of their time and treasure for the sake of some obscure Indian tribe thousands of miles away also fails the test of Dickensian orthodoxy. Thompson cites Pardiggle’s claim, “’I enjoy hard work; and the harder you make mine, the better I like it.’” Then he concludes, “Her work, however, does more harm than good” (39). Let’s now ponder the third character’s service to see how it fares.

Mr. Chadband "Improving a Tough Subject"

Reverend Chadband

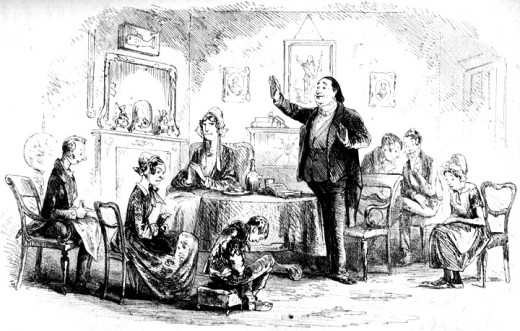

Without a doubt the most contemptible religious character in Bleak House is the Reverend Chadband. Dickens does not disguise his hatred for this man of no particular cloth, whose propensity for pompous, long-winded speeches and gluttonous, longer-winded repasts disgusts him. A taste of that disgust follows:

From Mr. Chadband’s being much given to describe himself, both verbally and in writing, as a vessel, he is occasionally mistaken by strangers for a gentleman connected with navigation; but, he is, as he expresses it, ‘in the ministry.’ Mr. Chadband is attached to no particular denomination; and is considered by his persecutors to have nothing so very remarkable to say on the greatest of subjects [. . .] .

Guster . . . the handmaid of Chadband, . . . knows [him] to be endowed with the gift of holding forth for four hours at a stretch, [. . .] .

For, Chadband is rather a consuming vessel—the persecutors say a gorging vessel; and can wield such weapons of the flesh as a knife and fork, remarkably well (303-4).

Guinn emphasizes that “Chadband is the epitome of meaningless religion” (127). When he attempts to “evangelize” Jo in his miserable condition, the reverend does not regard the boy as a wholistic individual, body and soul, but only as someone who does not cool himself in a “running stream of sparkling joy,” because “you are in a state of darkness, because you are in a state of obscurity, because you are in a state of sinfulness, because you are in a state of bondage” (Dickens 313-4). Guinn perceptively sees Chadband as “a Pharisee of the type described by Christ to his followers in Matthew’s gospel” (128). Among other verses, he cites Matthew 23:4 which describes Pharisees as those who “bind heavy burdens. . . on men’s shoulders, but . . . will not move them with one of their fingers” (128). Not only does Chadband not stoop to aid the boy physically, but he also offers no spiritual remedy for Jo’s “state of sinfulness.” He sounds like a rabid evangelist; the text gives no indication that he himself truly knows the answers. Though Dickens does not mention whether or not Chadband was an advocate of foreign philanthropy, the good "reverend" also fails the author’s examination because of his self-absorbed hypocrisy.

Ikeler summarizes the “ministries” of Chadband, Mrs. Pardiggle, and Mrs. Jellyby when he writes: “ . . . , in judging the philanthropic aggregate, we are led inexorably to identify their primary shared fault as destructive vanity in the mask of public commitment” (511). This is a fair assessment of that trio; their egos preclude worthwhile service. Let’s now consider three characters whose work represents a view of social responsibility closer to the Dickens ideal.

© 2015 glynch1