The Power of Names in Neveryóna and She Unnames Them

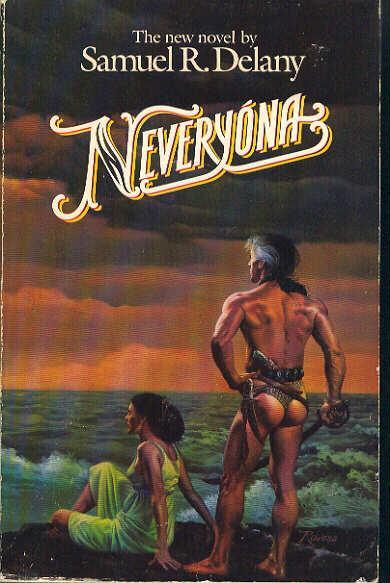

If the amount of books and websites dedicated to accumulating baby names is any indication, then naming is something that people take very seriously ( …Though celebrities seem to take the entire process a little less seriously than most or just have very odd tastes). And why shouldn’t they? Names are powerful little things with strong ties to a person’s identity that are hard to shake off and to separate from the person to which they are attached. Names make the universe more comprehensible and provide the building blocks for language. Yet, names, like everything else it seems, carry a price. Neveryóna, a novel by Samuel R. Delany, and “She Unnames Them,” a short story by Ursula K. Le Guin, both explore the power of names in different ways. Neveryóna deals with the idea of giving names, or at least setting names apart from mere things, while “She Unnames Them” takes names away. The presence of names and their conspicuous lack demonstrate both the gains of names and the sacrifices that they demand.

Neveryóna begins with the character of pryn who, the story tells us, knows “something of writing but not of capital letters” (471). When she meets a tale-teller named Norema she learns the convention of capitalizing the first letter of a name to convey that it’s the name of a person. The newly christened Pryn’s opinion on that convention is undisguised. “I like that!” she says (476). But why does she like it? Well, capitalizing names certainly lends some importance to the named. Plain old "heather" is just a plant, but "Heather" is an entity unto herself. Suddenly Pryn has found herself transformed from a noun into a proper noun. How very fancy. And after Pryn receives this capital she feels “very differently about herself” which points to how names help to shape identity (477). There are perceptions and associations that get attached to names—some are individual associations, some fall across a larger scale of stereotypes—and any person carrying a name has to deal with those associations, either by assimilating them into their personality or lashing out against them. So close is a person’s name to their identity that the common response to “Who are you?” is to simply say one’s name.

Yet, is a name equal to a person’s identity? Surely fifteen year’s worth of opinions and feelings and tastes and dreams cannot be collapsed down into something as short as Pryn. But that’s what names attempt to do. They squash down identity into something short—something that can be easily articulated—and inevitably leave the bulk of the person’s story out. The real danger is that this abridgement becomes a reality not just to those people who use the name, but to the individual who bears the name. They may realize that they are more than their name, but that "more" is an abstraction that they struggle to make clear—even in their own minds.

But clarity of expression is valuable. That’s why Norema from Neveryóna devises her system of capitalization for names. She very practically adopts this standard because, “that way,” she says, “if I’m reading it aloud, I can always glance ahead and see a name coming. You speak names differently from the way you speak other words. You mean them differently too” (476). Giving things names allows for distinctions to be made. In a wide and complicated world, the language of naming divides the world, classifies it, and re-imagines it. In short, it makes the incomprehensible comprehensible. Even the protagonist from “She Unnames Them” owns that her name has “been really useful” as she gives hers back (526). Communication without negotiating the world of names becomes very complicated and ambiguous and certainly leads to awkward questions. Take just the title of “She Unnames Them”; the obvious question that pops up from that is: “She unnames who?” And the only response that can be given is an echo of the protagonists own struggles to say who she’s leaving with: “them, you know,” is all she can manage (526). The next question is “Who’s she?” And in this nameless world one can only answer with “Oh… you know… her.” “Just her?” the inquisitor would continue. “Well, she’s Eve, I suppose,” a person could try to answer. “Only she gave that back, so she’s not really that anymore.” Getting anywhere in a conversation in a nameless world is a mess. In fact, the woman in the story confesses that she “had only just then realized how hard it would have been to explain [herself]. [She] could not chatter away as [she] used to do, taking it all for granted” (526).

But it is that very clarity that becomes a problem in naming. Separating things into easy-to-understand sections keeps groups closed off from each other. When the main character of “She Unnames Them” has taken back the names of all the animals of the world she reflects that afterword, “they seemed far closer than when their names had stood between myself and them like a clear barrier: so close that my fear of them and their fear of me became one same fear” (526). In naming any given group, that group is instantly cast as other, as alien from the rest. Naming defines identity by saying what one is by what one is not, yet it destroys identity by taking the place of the thing it names.

And surely, it is no surprise that the animals would want to shed their names. After all, they were given to them by someone else. That’s always the problem with names—with Pryn’s name and the animal names and with almost any name. They’re not usually something that a person gets to choose for his or herself, so a piece of someone else’s will is always imbedded in their personality. The namer casts a web of projected assumptions and associations onto the thing he or she names, choking it from making movements on its own. Frankly, it’s easy to see the titmouse and the blue-footed booby getting sick of all the snickering from those no-good humans and deciding to shed the ridiculous names they’d never asked for. And what about poor Apis cerana nuluensis? That’s a real bind to fit onto one name tag. And as for Eden, the serpent has never quite shaken of its reputation for being a wicked, tempting, forbidden-fruit-enthusiast. But whatever their reasons, the animals in “She Unnames Them” are very willing to let go of “all the Linnaean qualifiers that had trailed behind them for two hundred years like tin cans tied to a tail” (525). Names are a burden on the named, forever driving the named into unchangeable groups and boxing the individual into a construct of perceptions.

Not only that, but names are not very durable. At the end of the first chapter of Neveryóna, Pryn scratches her new, capitalized name on the ground before leaving her home for an adventure with her newfound identity marker. However, shortly after she leaves “a dead branch, blown out on the road by a mountain gust obscured it beyond reading” (484). Names only last as long as someone is around to read them or to say them. And names can be forgotten as well. The villagers forget that Pryn’s aunt was the one to invent the spindle and a method of weaving, thus obscuring her own achievements and fame. For something so fragile as a name to become the sole marker of identity is dangerous, because when the name fades away, so does the individual. Perhaps breaking the attachment names have early on as in “She Unnames Them” is better than allowing them to entangle around someone, choke out their identity, and leave nothing left when they fade away.

But what about renaming? Surely that’s a less drastic step than cutting out names altogether. And people do steal themselves away from the identity and the life that whoever named them set up for them in advance—with greater or lesser degrees of success. Despite the fragility of names, they have a certain tenacity. Many a young person in a desperate, misunderstood search for their true nature has found that the cruel world will give them the name of “That Katie girl who goes around calling herself Desdemona Moonlust.” Names are never something decided solely by the person who bears them. Often times they’re picked out by the person who wears them—stage names or pen names—but it’s only a name if someone besides the person calls themselves that. And the change in name always marks a change in identity and attitude. That’s how personas emerge. “Norma what?” they say. “Oh no. That will never do.” And suddenly a new person is born out of the old. “Choose a username,” the dialogue box instructs and suddenly Jeff Madison carries the handle of ThornWolf355. But which is real? Is either? “She Unnames Them” doesn’t create more symbols to add to the “hundreds of thousands of different names since Babel,” but does away with the messy layering business altogether and avoids causing internal schisms, opting for a more communal sense of being instead (525).

Despite the limitations of names, they are likely to stay around instead of going the route of “She Unnames Them.” As that story itself admits, they are useful. And as Norema in Neveryóna explains they “[distinguish] people from things in and of the land” which “makes tale-telling make a lot more sense” (476). Names are convenience items—the nuts and bolts of communication. But like all convenience items, their luxury carries a price. Names do not tell the whole story, and that is what both Neveryóna and “She Unnames Them” are a reminder of. It is hard to use names as mere tools of communication and not let them become something more. When the symbol eclipses the thing it symbolizes it as good as destroys it and even worse assumes its form. Names are powerful, violent and not to be taken lightly.

References

Delany, Samuel R. Neveryóna. Postmodern American Fiction: A Norton Anthology. Paula Geyh, Fred G. Leebron, and Andrew Levy. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc, 1998. 471-484. Print.

Le Guin, Ursula K. “She Unnames Them.” Postmodern American Fiction: A Norton Anthology. Paula Geyh, Fred G. Leebron, and Andrew Levy. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc, 1998. 525-526. Print.