Analysis of "The Flea" by John Donne: The Raciest 17th Century Poem You'll Ever Read

From "The Flea"

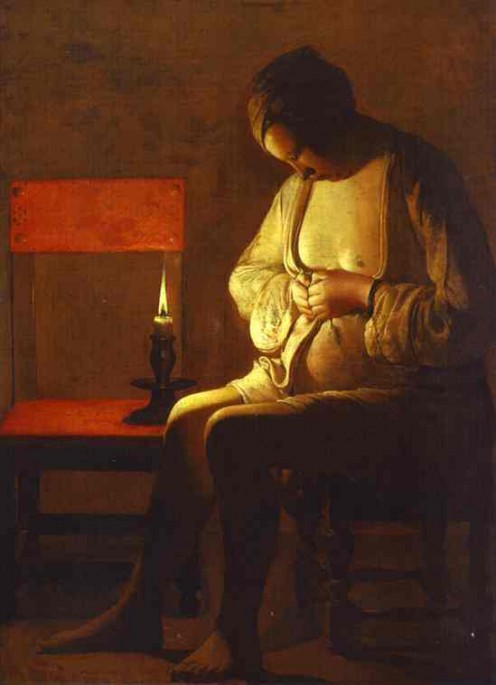

John Donne’s poem “The Flea” is probably sexiest 17th century poem you will ever read. It could be considered the first poetic instance of a young man using a ridiculous argument to try to convince a woman to go to bed with him. The poem focuses on a flea that has bitten two lovers, so that their blood combines it. The narrator claims that this mixture of blood, “one blood made of two” (9), is the same as sexual intercourse. He argues that since the lovers have metaphorically consummated, (and even produced a child!) within the flea with no ill effect, then there should be no consequences to performing the same act without the intermediary of the flea, i.e. in real life.

The Argument

Donne uses the device of conceit, or an elaborately sustained metaphor between two unlike things to advance the argument. The conceit is introduced when Donne compares the union of blood within the body of the flea to the sexual act. The conceit is sustained as the flea becomes a microcosm for the world outside the flea. Because the lovers are “cloistered in these living walls of jet” (15), they have formed a union that can be compared to marriage.

“Oh stay, three lives in one flea spare (11), writes Donne. The three lives mentioned here insinuate that a child has come out of the “marriage," which also gives further evidence that the couple has indeed consummated their love within the microcosmic world of the flea-- consummation being necessary for procreation. This microcosm is continued through the second stanza, at the end of which the young lady is warned not to kill the flea because she will be “killing” their family.

In the third stanza the young lady does kill the flea, getting blood on her nail. But even though she has killed the flea, the narrator claims that she “Find’st not they self nor me the weaker now” (24). The microcosm within the flea has been destroyed, but neither of the lovers are worse for the wear with their figurative selves destroyed.

Denial That There are Consequences to Sex

Even though the fact that the death of the lovers within the flea doesn't seem to have any effect in the real word could potentially contradict Donne’s argument, he actually uses this to further the conceit. Because he had feared that harm would arise from killing the flea, and yet there was none, the young woman should cease her worries. Without consequence to the union within the flea, or in the killing of the flea, there should not be any consequence for a sexual union in real life: “Just so much honor, when thou yield’st to me,/ Will waste, as this flea’s death took life from thee” ( 26-27).

What Donne hopes to achieve as narrator of the poem is sexual contact with the lady, who is portrayed as a virgin. “A sin, or shame, or loss of maidenhead” (6), the sexual interaction that the flea enjoys, is “alas, more than we would do" (9). Within the poem, the flea is allowed liberties that the man is not. What Donne hopes to achieve as a poet is somewhat different. The conceit of the flea equaling consummation serves to showcase the wit of the poet, the skill employed in not only creating the metaphor but in managing to sustain it throughout the entire poem.

Love as a Physical Act

"The Flea" compares quite differently to traditional metaphors of love. It likens it to an unusual metaphor, a parasite, rather than something of beauty, like springtime, flowers, or the outdoors, all common images of love poetry during the time.

The poem is very sensual, even sexual, contrary to how most 17th century writers described love and desire. Rather than making love out to be something that is pure and lofty, Donne alludes quite freely to the act of sex. “The Flea” speaks about the act of conception, virginity, and the “marriage bed” (13), in a surprising manner for the time, and indeed one could argue, even in the modern day.

Full Version

- The Flea- Full Text

Read the full poem at PoetryFoundation.org