“Cyrus West Field (1819-92): Laying the Atlantic Cable, 1866; A Dialogue.”

“Cyrus West Field (1819-92): Laying the Atlantic Cable, 1866; A Dialogue.”

By Franklin Parker and Betty J. Parker, bfparker@frontiernet.net

(First published by the authors as “Laying the Atlantic Cable, 1866: A Social Studies Dialogue, “Review Journal Philosophy and Social Science, Vol. 29 Special Issue (2004), pp. 103-124.

Introduction

In its time the laying of the Atlantic Cable in 1866 was a far reaching technical achievement. It was an important historical event, first, as an early example of international technical cooperation, specifically among Canada, the U.S.A., and Britain. Secondly, it was important in science, technology, international relations, and international business. In many ways the Atlantic cable helped make the modern world possible.

Dialogue

Betty: Why is the history of the 1866 Atlantic cable worth knowing? Why share this topic in dialogue form for high school and college students as well with other general readers?

Frank: We have forgotten how important the Atlantic Cable was and what U.S. life was like in the 1850s and 60s. The story of the Atlantic Cable reminds us that Europe then dominated the world. Britain was its political and financial center. The U.S.A. was a far away backwater country separated from Europe by a wide and stormy North Atlantic.

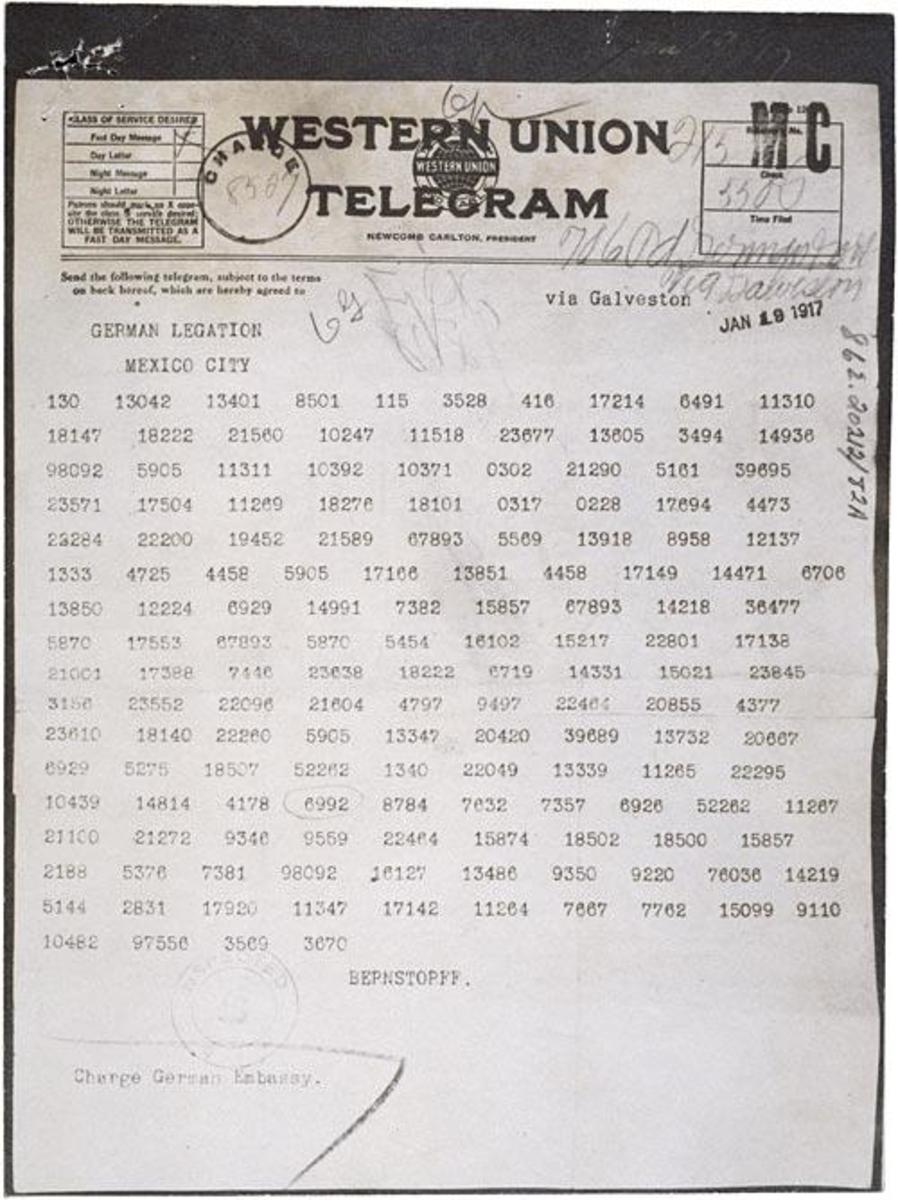

Betty: It took weeks for letters, goods, and people to cross the Atlantic on a ship considered fast for the time. Then, on July 27, 1866, to the world's amazement and on the fifth attempt over a 12-year period, the Atlantic cable, spearheaded by U.S. businessman Cyrus West Field, instantly connected New York with London.

Frank: John Steele Gordon's Thread Across the Ocean: The Heroic Story of the Transatlantic Cable (see Sources at end) concluded that the Atlantic cable electrified people in 1866, changed history forever, helped make the U.S. a major player on the world scene, and created the beginning of the world as a global village.

Betty: This great 19th century engineering feat was an epic struggle costing millions, involving British, U.S., and European politicians, financiers, ships, sailors, technicians, and scientists.

Frank: The Atlantic cable was an early instance of international cooperation. It followed decades of U.S.-British angers over the American Revolution, the War of 1812, and frictional Civil War incidents. There were failures and disappointments in attempts at laying the Atlantic cable but it finally ended in a history-changing victory.

Betty: Historians have compared the successful completion of the transatlantic cable, July 27, 1866, to the U.S. landing on the moon, July 1969, 103 years later. Frank, tell us: What U.S. and British national factors hastened the laying of the cable? What technical developments, inventions, and economic factors made the Atlantic cable possible?

Frank: Americans in the early 1800s were little better off than the ancient Greeks or Romans in travel time and in speed of communications. Christopher Columbus took a month to reach the New World in 1492. The Mayflower took 23 days to cross the Atlantic in 1619. When the Atlantic cable was completed, the average ship using sail or steam still took several weeks to cross the Atlantic.

Betty: The Industrial Revolution of the 1700s and 1800s changed life by making goods and services faster and cheaper and more available than ever before. It is worth recalling exactly how this occurred.

Frank: Weaving cloth, the basis of the British economy, was advanced by British inventor John Kay's (1704-64) flying shuttle and by the inventors of the spinning jenny and the water-driven power loom. Scotsman James Watt's (1736-1819) steam engine increased textile factory output; and, when applied to cars on rails, increased and speeded the movement of people, goods, and services. The economy and life conditions improved, especially in Britain, Western Europe, and the U.S.A.

Betty: George Stephenson's (1781-1848) first successful steam locomotive the Rocket on the Manchester to Liverpool railway helped spread railroad lines around the world.

Frank: The middle class grew. New wealthy factory owners, open to ideas, replaced landed gentry in influence. After Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo, peace enabled Europe to turn its energies from war to commerce and industry.

Betty: In the U.S., Eli Whitney's (1765-1825) cotton gin, a rotating drum with spikes, efficiently pulled cotton fiber from its seed. It made cotton king in the South. New York City, which became the U.S. financial center partly by financing cotton sales abroad, grew in wealth and power.

Frank: Understanding electricity, essential in developing the telegraph, was hastened by Benjamin Franklin's (1706-90) key hanging from a kite in a thunder storm.

Betty: Lightning from clouds to earth was recognized as the release of built-up differences in potential. Chemical batteries were developed that gave carbon a positive charge and zinc a negative charge.

Frank: A connecting copper wire between differences in potential allowed an instant flow of electric current. England's Sir William Watson (1715-87) in 1747 proved that an electric current could travel a long distance along a copper wire.

Betty: On May 24, 1844, Samuel F.B. Morse (1791-1872) used a sending key to make and break an electric circuit. This start and stop of electric flow at the receiving end, which had a highly coiled wire, made it an electromagnet which attracted and repelled a piece of metal, producing a click-clack sound.

Frank: The Morse code: dot-dash (or dit-dahhh) for A; dahh, dit dit dit for B, dit dit dit dahh for V, and so on, made telegraph messages possible. Morse's first message on the telegraph wire between Baltimore and Washington, D.C., was: "What Hath God Wrought?"

Betty: Another change: Canals replaced slow and costly hauling of mid-west farm products over the Allegheny Mountains to eastern markets. The Erie Canal, connecting Lake Erie with the Hudson River at Albany allowed cheaper, faster access along the Hudson River to New York City.

Frank: Between 1800 and 1860 the amount of U.S. commerce passing through New York City rose from only 9% to 62%. New York City became the biggest boom city in the world. In 1835, on the upswing of that boom, 16-year-old Cyrus West Field left his native Stockbridge, Mass., to seek his fortune in New York City.

Betty: Unlike his seven older brothers who attended Williams College, Cyrus Field persuaded his Congregational minister father to let him seek work in New York City. There a brother arranged his apprenticeship in A. T. Stewart's (1803-76) dry goods department store, the biggest in New York City, which later became John Wanamaker's (1838-1922).

Frank: After his apprenticeship at A.T. Stewart's department store, Cyrus W. Field joined his brother Matthew Field, a partner in a Massachusetts paper mill. From bookkeeper, Cyrus became a leading salesman of paper supplies in New York state and throughout New England.

Betty: Field then became a junior partner in E. Root & Co., a New York City paper wholesaler. That firm failed after the Panic of 1837. Field acquired its paper stock. Although not himself liable, he settled the firm's debts at 30 cents on the dollar. His own firm, Cyrus W. Field and Co., became the leading U.S. wholesaler of paper and printing supplies.

Frank: Wealthy, living in New York City's fashionable Gramercy Park, Field soon paid all of E. Root & Co.'s debts, although not obligated to do so. The golden reputation he earned enabled him later to raise millions from investors for the Atlantic cable.

Betty: Still in his 30s, Field gave the management of his own firm to others and looked for new worlds to conquer. In November 1853, his brother Matthew introduced him to a Canadian engineer Frederick Gisborne (1814-80). That meeting changed Field's life.

Frank: Canadian Frederick Gisborne, a self-taught engineer, headed the Nova Scotia Telegraph Co. Nova Scotia, with its main city of Halifax, is a Canadian peninsula in the Atlantic, northeast of Portland, Maine. To Nova Scotia's northeast is Newfoundland, fourth largest island in the world. Its main city, St. John's, is North America's nearest point to Ireland, England, and Europe.

Betty: Gisborne was trying to build a telegraph line from St. John's, southwest to Cape Ray, Newfoundland, there to connect through a submerged cable under Cabot Strait in the Atlantic to Cape Breton Island; and continuing into Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia was already connected by telegraph lines to Portland, Maine, Boston, and New York. Gisborne, out of money, his cable incomplete, was bankrupt.

Frank: Field asked: Why are you trying to build your telegraph line from St. John's to Nova Scotia? Gisborne replied: So that ships carrying news from Europe landing at St. John's can telegraph that news to New York City, saving a day or two.

Betty: Cyrus Field was not impressed. For European news to reach New York one or two days earlier was not worth his time or trouble. Later, at home, looking at his world globe, Field realized that to send an almost instant telegraph message by a cable submerged in the Atlantic Ocean between Ireland and Newfoundland and then to New York, would be worthwhile and could be profitable.

Frank: November 9, 1853, the day after talking to Gisborne, Field wrote Samuel F. B. Morse to ask if an Atlantic cable was a practical possibility. Yes, answered Morse. He had experimented with an underwater telegraph line in New York harbor in 1843 and was confident it could be done. Morse offered to help.

Betty: Field also wrote to Lt. Matthew F. Maury (1806-73), head of the U.S. Navy Charts and Instruments and an expert on ocean winds and currents. Lt. Maury replied that the U.S. Navy had just completed a survey of winds and currents and made depth soundings in the most traveled U.S. to Europe shipping lanes. Maury ended: "…between Newfoundland…and Ireland the practicality of a submarine telegraph across the Atlantic is proved."

Frank: Needing capital Cyrus Field turned to his Gramercy Park neighbor Peter Cooper (1791-1883). Cooper had made a fortune in a glue factory and then built the first locomotive for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Cooper was then organizing Cooper Union, a tuition-free night technical school for working adults. Field's cable plan stirred Cooper's yearning to serve mankind.

Betty: To Cooper, Field's Atlantic cable idea fulfilled the Biblical prophecy that "knowledge shall cover the earth, as the waters cover the deep." Cooper told Field: you find other investors and I will support you.

Frank: Field persuaded three wealthy men to become investors: 1-Moses Taylor (1806-82), controller of New York City's gas lighting industry; 2-Chandler White, who made a fortune in the paper business; and 3-Marshall O. Roberts (1814-80), a major ship owner.

Betty: The investors, with Frederick Gisborne, Samuel F.B. Morse, and Cyrus Field's attorney brother, pored over maps and charts. They absorbed Gisborne's telegraph company into their newly formed New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Co.

Frank: The Newfoundland government hoped for economic benefit. It granted the new company a 50 year charter and some financial aid. On May 8, 1854, Peter Cooper became president, Cyrus Field was chief operating officer, and other officers were named. They committed themselves to raise $1.5 million, a huge sum then, but as problems mounted, not nearly enough. Cyrus Field wrote 14 years later: "God knows that none of us were aware of what we had undertaken to accomplish."

Betty: In early 1855 brother Matthew Field supervised 600 workers completing the telegraph line across southern Newfoundland. Cyrus Field went to England for advice about the cable. He spoke to John Watkins Brett (1805-63), expert in submarine telegraphy who, with his brother Jacob Brett, had in 1851 successfully laid a 22 mile telegraph cable under the English Channel between Dover and Calais, France.

Frank: John W. Brett suggested a cable of three twisted copper wires, each covered with a new insulator, called gutta-percha. Bundled together, the wires were wrapped in tarred hemp, covered with another layer of gutta-percha, and the whole sheathed in galvanized iron wire.

Betty: Gutta-percha came from trees grown in Malaysia. Unlike rubber, gutta-percha did not break down in cold salt ocean water but hardened, yet was supple, a perfect insulator.

Frank: The cable, made in England, was placed on the steamship Sarah L. Bryant, which headed across the Atlantic to lay the cable under the Cabot Strait, south of Newfoundland.

Betty: In Canada Field chartered the James Adgar to tow the Sarah L. Bryant across the Cabot Strait as it laid the cable. Field entertained aboard the Sarah L. Bryant the Peter Coopers, the Samuel Morses, Field's two daughters, and two nationally known clergymen. Buffeted by storms and distracted by the partying guests, the towing ship's Captain Turner rammed the Bryant.

Frank: The cable kinked and, to prevent its weight already in the water from dragging the Bryant under, the cable was cut and lost.

Betty: It was a painful lesson. The delicate maneuver to be learned was how to coordinate cable laying speed and braking mechanism with cable weight, ship's speed, wind gusts, weather changes, and shifts in currents. It had to be learned by trial and error.

Frank: The cost of failure to lay a cable under the Cabot Strait in August 1855 was $351,000. The cable was finally laid under the Cabot Strait in late 1856 and the telegraph line completed from Newfoundland to New York City, about 1,000 miles. Total cost, $500,000, a third of the firm's capital. Field returned to London in 1856 to raise more money.

Betty: The British government, wanting rapid communication with its far-flung empire, backed Field with cable laying ships and a £14,000 annual subsidy (that was $70,000 a year).

Frank: This subsidy gave British government messages priority over private messages. The exception was--U.S. government priority over British government, if U.S. support matched Britain's support.

Betty: Encouraged, Field, in London, formed the Atlantic Telegraph Co. (October 1856) and sold shares worth £350,000 (U.S. currency equivalent of $l.75 million).Frank: The U.S. Congress hesitated to match Britain's offer. Some in Congress doubted that the cable would work. Others said that the rich cable backers should pay their own way. Others were traditionally anti-British. The Senate passed the needed legislation by one vote, the House by a few more. Pres. Franklin Pierce signed the aid bill on March 3, 1857.

Betty: Atlantic Ocean soundings between Newfoundland and Ireland made by a U.S. ship and a British ship determined the best cable route.

Frank: Added to the team were British chief engineer Charles T. Bright (1832-88), who chose Valentia Bay, Ireland, as the best cable connection port.Betty: Also added as advisor was Glasgow University Professor William Thomson (1824-1907, later Lord Kelvin). William Thomson, described by later historians as half Albert Einstein-half Thomas Edison, invented the galvanometer, which precisely measured electric current variations in the cable.

Frank: No single ship at the time was big enough to carry the new, thicker, heavier 2,500 mile long cable. In July 1857 the cable was divided between the USS Niagara and the HMS Agamemnon. Samuel F.B. Morse's plan was followed: both ships to start from Ireland, one laying its cable, a splice made in mid-Atlantic, with the other ship laying its part of the cable to Newfoundland.

Betty: Both ships set out from Ireland, each loaded with the 1,250 mile long carefully coiled cable. August 6, 1857: the cable was caught in the braking machinery. It broke. It was spliced. And the brake speed was adjusted.

Frank: By August 8, 1857, 85 miles of cable had been laid. Two days later, August 10, the electric signal in the cable faded, was revived, and the cable, after being laid 400 miles, broke and sank. The first Atlantic cable attempt of 1857 had failed.

Betty: Cyrus Field returned to a New York City hard hit by the financial Panic of 1857. His own paper firm was in debt. Always optimistic, Field went to Washington, D.C., and got the U.S. Navy to lend him the USS Niagara and the USS Susquehanna.

Frank: The Navy also assigned him the Niagara's engineer William E. Everett (1826-81) as the Atlantic Cable Co.'s chief engineer. Engineer Everett built more efficient cable laying and braking systems. Glasgow University's Professor Thomson built a more efficient marine galvanometer to measure cable electric currents more precisely.

Betty: During spring and summer 1858 a second cable laying was attempted. Engineer Charles Bright's plan was followed: one ship laid cable from Ireland, the other from Newfoundland. They were to meet and splice their ends of cable together. On June 13, 1858, as the two ships approached each other, the worst North Atlantic storm in memory buffeted them mercilessly.

Frank: Coal bins on deck broke loose. Coal dust, mist, fog, and mountainous waves caused a cable break; 45 seamen were in sick bay, some with broken bones. The second cable laying attempt of 1858 had failed.

Betty: In London, gloomy and defeated, the Atlantic Cable Co. chairman and vice chairman resigned. They advised their fellow board members to sell all assets and liquidate the company. Staggered, Field used all of his persuasive powers to hold the remaining board members. True, he told them, 300 miles of cable had been lost. But there is still enough cable on the ships to complete the job. Let us try again.

Frank: Try again they did in 1858, with short-lived success. The cable worked for two weeks. Some 400 messages were exchanged. The signal then disappeared. Elation turned to despair. Press and public dismissed the cable as a waste of time and money. Here is what happened.

Betty: On July 17, 1858, the cable laying fleet left Ireland, this time without cheering crowds. In August 1858 the cable laying ships grappled the ocean floor for the broken cable ends. Cable ends were found, raised, spliced and the electric signal was faint but grew stronger.

Frank: On August 5, 1858, the USS Niagara approached Newfoundland. The signal from HMS Agamemnon nearing Ireland still worked. Elated, the USS Niagara crew docked at Trinity Bay, Newfoundland. At the nearest telegraph station Field telegraphed his wife, father, Peter Cooper, the Associated Press, and U.S. President James Buchanan (1791-1868): "The cable is laid. …By the blessing of Divine Providence it has succeeded."

Betty: The HMS Agamemnon docked in Valentia, Ireland, its signal with the USS Niagara in Newfoundland still working. Engineer Charles T. Bright telegraphed the London board of directors and the press: "The Agamemnon has arrived in Valentia [Ireland], and we are about to land the cable. The Niagara is in Trinity Bay, Newfoundland. There are good signals between the ships."

Frank: Not knowing that this connection would last only a few weeks, David Field wired enthusiastic praise to his brother Cyrus.

Betty: On August 16, 1858, Queen Victoria (1819-1901) cabled congratulations to Pres. James Buchanan. But the signal was weak. It continued weak for a time, stopped, and remained silent. Public jubilation turned to scorn. Newspapers that had lionized Field now lampooned him. Friends and partners avoided him. But staunch Peter Cooper told Field: "We will go on."Frank: The Civil War, however, drained U.S. resources. Field could not find U.S. investors. British leaders, still wanting quicker communication with their empire overseas, formed a commission of inquiry to find what errors had been made and how to set them right.

Betty: The commission found, five years later (July 1863): 1. That Cyrus Field's lack of expert advice led to the 1857 failure. 2. That a substitute cable voltage measuring device had permitted high voltage to burn out the cable during the first and second 1858 attempts. 3. That cable laying would be more manageable if done by a single large ship.

Frank: The ideal ship for laying the cable was the Great Eastern, the largest ship of its time. It had been launched November 3, 1857, as an Atlantic passenger ship.

Betty: The Great Eastern had two iron hulls and water tight compartments. Its powerful steam engines propelled both a screw-driven propeller and two enormous side paddle wheels. It had five smoke stacks and six sail masts to catch the wind.

Frank: Earlier, Field had met I.K. Brunel (1806-59), Great Eastern's designer, when traveling from Valentia, Ireland, to London. Brunel took Field to see the Great Eastern then being built and said prophetically to Field: "Here is the ship to lay your cable."

Betty: But it was the 1861 Trent Affair, an incident that provoked near war between the U.S. and Britain, that persuaded Cyrus Field to contact U.S. Secretary of State William Henry Seward (1801-71). That contact and Field's success in finding investors in London revived the Atlantic cable attempt and involved the Great Eastern.

Frank: The Trent Affair began on October 11, 1861, when Confederate agents James M. Mason (1798-1871) and John Slidell (1793-1871s) slipped through the Union blockade at Charleston, S.C. They went by ship to Cuba and there boarded the British ship Trent. The Confederate agents were heading for England and France to raise money and arms for the South.

Betty: November 8, 1861: USS San Jacinto's Capt. Charles Wilkes (1798-1877), on his own, stopped the Trent with canon shot, boarded her, forced Mason and Slidell's removal, and imprisoned them.

Frank: Britain, officially neutral, protested this illegal seizure of passengers from a British ship as an act of war. Britain demanded an apology and the prisoners' release. Angers flared. Anticipating war with the U.S., Britain ordered troops sent to Canada.

Betty: On November 24, 1861, in Washington, D.C., President Lincoln (1809-65) discussed the Trent Affair with his Cabinet. Lincoln told them: one war at a time, gentlemen. He disavowed the illegal seizure, stated that Capt. Wilkes had acted on his own, and ordered the Confederate agents released.

Frank: Cyrus Field immediately saw that had the Atlantic Cable been operating, rapid government exchanges would have explained Capt. Wilkes's rash act, resolved the incident, and Britain would have avoided large military expenditure. Field shared these thoughts with U.S. Secretary of State William Seward. Seward agreed with Field and instructed the U.S. Ambassador in London Charles Francis Adams (1807-86) to help Field raise more British funds for a new cable attempt.

Betty: A greater irritant to U.S.-British relations that happened during the U.S. Civil War was later called the Alabama Claims. The Confederacy, without a navy of its own, secretly bought British-built ships and armed them as raiders. One such ship renamed CSA [Confederate States of America] Alabama sank many Union ships, causing loss of lives and cargo.

Frank: After the Civil War an international court arbitrated the Alabama affair and required Britain to pay the U.S. $15.5 million indemnity for illegally selling ships to the Confederacy.

Betty: Despite these irritants, Field, in London, secured from the British government an increase in the annual subsidy to £20,000 (about $100,000 a year), provided the cable worked. Field still could not find investors in the U.S. which was mired in Civil War.

Frank: January 1864: Investors Field found in England included railroad contractor Thomas Brassey (1805-70) and House of Commons member John Pender (1816-96). Field negotiated with a new gutta-percha company to manufacture an improved cable. That company's officials also agreed to invest £315,000 (just over $1.5 million) in Atlantic Telegraph Co. shares. Best of all, Field contacted the Great Western Railway's head, Daniel Gooch (1816-89), who formed a syndicate to buy and use the Great Eastern as the cable laying ship.

Betty: On July 23, 1865, the Great Eastern under Capt. James Anderson (1824-93), with attendant ships, left Valentia, Ireland, to lay cable to Heart's Content, Newfoundland. The Great Eastern carried 21,000 tons. This included the heavy new coiled cable to be laid using an elaborate new braking system. It also included a 500-man crew, scientists, and experienced cable technicians, all British subjects except Cyrus Field. It carried live animals aboard for food (no refrigerated ships then).

Frank: An electric signal sent on the cable from Valentia was monitored by the galvanometer aboard the Great Eastern as it laid cable. When that signal weakened or stopped, cable laying stopped, the cable was reeled back aboard ship until the bad spot was located, repaired, spliced, and cable laying was then continued.

Betty: On August 2, 1865, after 1200 miles of cable laying, a mechanical mishap caused the cable to break less than 600 miles from Newfoundland. Using grapples, the cable end was found but could not be brought up from the ocean depth. With grappling rope gone and supplies short, Capt. Anderson marked the exact position of the lost cable end by sextant readings and buoy markers and headed back to Ireland.

Frank: Instead of derision, Field found himself acclaimed as a hero in England. Press and public applauded the fact that the cable had been laid two-thirds the way across the Atlantic. Encouraged, the Atlantic Telegraph Co. directors raised new capital. The plan for the new try in 1866 was to lay a whole new cable from Ireland to Newfoundland; then, on the way, retrieve the lost 1865 cable, splice it to new cable and have the incomplete first one serve as a second cable line.

Betty: A legal difficulty prohibited the Atlantic Telegraph Co. from selling stock for a year. This delay led its directors to create a new Anglo-American Telegraph Co. Shares were sold. Money was raised. A better cable was manufactured. Better cable laying machinery was constructed. The Great Eastern was made sturdier for cable laying.

Frank: On June 30, 1866, the Great Eastern left the Thames Estuary, England. It flew U.S. flags on July 4, 1866, off the Irish coast. On July 13, 1866, fixing one cable end to its Irish port location, the Great Eastern laid cable toward Heart's Content, Newfoundland.

Betty: The Great Eastern crew, more professional, efficient, disciplined, and motivated than on previous attempts, made good time laying cable. The ship's 1866 route paralleled but avoided tangling with the 1865 cable whose end the captain intended later to find, splice, and use as a second cable line.

Frank: On July 24, 1866, the Great Eastern passed the point where the 1865 cable end lay. Three days later, July 27, 1866, was the magic day.

Betty: The rain had stopped. The fog had lifted. The Great Eastern reached the fishing village of 60 homes and a church with the quaint name of Heart's Content, Newfoundland. The cable end, taken ashore, was connected to a land telegraph line.

Frank: The electric signal from Valentia, Ireland, to Heart's Content, Newfoundland, was loud and clear. When this fact was confirmed, bells rang. People shouted. Cyrus Field telegraphed the Associated Press: "…We [have] arrived…. Thank God, the cable is laid, and is in perfect working order."

Betty: A New York Times article, July 31, 1866, p. 1, stated: Queen Victoria cabled congratulations to U.S. Pres. Andrew Johnson (1808-75). Within the hour the U. S. President replied to Her Majesty. On the same day the mayors of New York City and London exchanged cable greetings. A New York Times, August 4, 1866, p. 1, c. 7, was headlined: "The Atlantic Telegraph. Immense Success of the Great Enterprise."

Frank: Queen Victoria showered knighthoods on British cable participants: Sir Charles T. Bright, engineer; Sir Samuel Canning (1823-1908), engineer; Sir William Glass, cable manufacturer.

Betty: Sir James Anderson, Great Eastern's captain, Sir Daniel Gooch, who secured the Great Eastern as the cable ship; and Sir Curtis Lampson (1806-85), Atlantic Cable Co.'s deputy chairman.

Frank: Glasgow University Professor William Thomson, who invented the galvanometer, was named Lord Kelvin. At his death he was honored by burial in Westminster Abbey.

Betty: Queen Victoria would have also handsomely honored Cyrus W. Field had he been a British subject. The British press soon dubbed him "Lord Cable." The U.S. Congress awarded him a gold medal in March 1867.

Frank: Field, rich again, paid his debts, built New York City's Third and Ninth Avenue Elevated Trains, and owned two New York City newspapers. But he was not a good investor. He lost about $6 million.

Betty: Field died in 1892. His tombstone in Stockbridge, Mass., reads: "Cyrus West Field To whose courage, energy and perseverance the world owes the Atlantic telegraph." Frank, could anyone else but Cyrus W. Field have successfully laid the Atlantic cable?

Frank: Someone might have. But no one did. He alone came forward. He persisted to the successful end. He alone pursued the Atlantic cable idea for 12 years, through five attempts. He alone convinced investors, raised funds, and coordinated U.S. and British scientists, engineers, ships captains and crews. He made the Atlantic cable an international affair. He got the U.S.A. and Britain, two nations historically at odds with each other, to work together. He brought together the old and the new world.

Betty: Although always seasick he made 50 Atlantic crossings. He used his skill, drive, personality, and determination to make the Atlantic cable succeed. Not until the 1960s did satellite communication supplement but not replace the cable. Frank, what did the Atlantic Cable accomplish?

Frank: The Atlantic Cable revolutionized communication in business, government exchanges, and international news. It also made the haves aware of the have nots, and visa versa, another kind of ongoing revolution. Betty, what do we owe this man?

Betty: Author John Steele Gordon's very last sentence in his book says it all: "[Field] laid down the technical foundation of what would become, in little over a century, a global village." What we have long needed do is to work for peace in this global village we call earth.

Afterword

Questions students and other readers may answer and discuss:

Name and describe the most influential leaders who helped lay the 1866 Atlantic Cable.Which leaders were most crucial in this endeavor and why?

Describe economic, social, technical, and other developments necessary for the successful laying of the cable.How was the laying of the cable financed?

What were the important consequences of the successful laying of the cable?

What part was played in the laying of the Atlantic Cable by the telegraph, the galvanometer, gutta-percha, oceanic studies, and other inventions?

How did the U.S. Civil War affect the laying of the Atlantic Cable?Compare Britain's interest and greater political need for the Atlantic Cable as against the U.S.A's interest and need.

Book Sources

1. Buchwald, Jed Z. "Thomson, Sir William (Baron Kelvin of Largs)," Dictionary of Scientific Biography, ed. by Charles C. Gillispie (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1976), Vol. XIII, pp. 374-388.

2. Dunsheath, Percy, ed. A Century of Technology (New York: Roy Publishers, 1951), pp. 272-273.

3. Gordon, John Steele. Thread Across the Ocean: The Heroic Story of the Transatlantic Cable (New York: Perennial, 2002), 240 pp. This book, the primary source used in this article, is reviewed in: a-Internet URL: http://www.walkerbooks.com/books/catalog.php?key=226 and b-Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute, Vol. 128, Issue 9 (Sept. 2002), p. 90.

4. John, Richard R. "Field, Cyrus West," American National Biography, ed. By John A. Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), Vol. 7, pp. 876-878.

5. McNeil, Ian, ed. An Encyclopedia of the History of Technology (London: Routledge, 1990), p. 715.

6. Singer, Charles, et al., eds. A History of Technology (Oxford: Clarendon Press), Vol. 4, pp. 225-226, 660-661.

Internet Sources

1-"Atlantic Cable," http://www.sil.si.edu/digitalcollections/hst/atlantic-cable/sil4-0045.htm

2-Canso and Hazel Hill, "Transatlantic Cable Communications; 'the Original Information Highway.'"

http://collections.ic.gc.ca/canso/earlycab/tech.htm#transatlantic3-"1866, Cyrus Field, The Laying of the Atlantic Cable," http://207.61.100.164/candiscover/cantext/science/1866fiel.html

4-"Field, Cyrus West (1819-1892)," http://74.1911encyclopedia.org/F/FI/FIELD_CYRUS_WEST.htm

5- _________________________. Short sketch and 1858 photo of C. W. Field taken by Civil War photographer Mathew Brady, original in National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. http://www.npg.si.edu/exh/brady/gallery/78gal.html

6-[Great Eastern]. http://www.greatoceanliners.net/greateastern.html

_____________. http://www.scripophily.net/eassteamnavc.html7-Harding, Robert S., and Mumia Shimaka-Mbasu, "Anglo-American Telegraph Company, Ltd. Records, 1866-1947." http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives/d8073.htm

8-"History of the Atlantic Cable & Submarine Telegraphy From ...1850, to the present day ....", http://www.atlantic-cable.com/, is a near exhaustive Atlantic Cable database. It includes a Cable bibliography; a Cable timeline from 1850; early British, Canadian, and U.S. Cable experimenters; and articles on the 1858, 1865 and 1866 transatlantic Cable laying attempts. It has photos of and articles about Cyrus W. Field and others connected with the 1854-66 cable laying attempts, including the Great Eastern and other involved ships.

9-"History of Telecommunications from 1840 to 1870," http://www.2.fht-esslingen.de/telehistory/1840-.html#1866

10-"John Steele Gordon," Rotary Club of New York. http://ussterilizer.com/bulletin_08-26-2003.pdf

11-"Laying the First Transatlantic Cable," http://www.infoplease.com/askeds/4-14-01askeds.html

12-"Manufacture of the Atlantic Telegraph Cable, from Illustrated London News, 1857," http://www.victorianlondon.org/communications/telegraphcable.htm

13-"Samuel F.B. Morse," http://www.invent.org/halloffame/106.html

14-"Sir James Anderson [Capt., Great Eastern], 1824-1893," http://www.newman-family-tree.net/Sir-James-Anderson.html

15-"The Transatlantic Cable." http://www.history-magazine.com/cable.html

New York Times (chronological order)

1. "Telegraph, Atlantic." New York Times Index: A Book of Records. Sept. 1851-Dec. 1862. Page 294 (entries for Sept. to Dec. 1858), page 325 (1859). See also same topic in 1860 and 1862.

2. "Atlantic Cable," July 29, 1866, p. 4, c. 7. July 30, 1866, p. 1, c. 1-4.

3. "Ocean Telegraph," July 31, 1866, p. 1, c. 6-7.

4. "Atlantic Telegraph," Aug. 2, 1866, p. 5, c. 4. Aug. 4, 1866, p. 1, c. 7.

END of Manuscript. bfparker@frontiernet.net