Credential Inflation in the United States of America: A Discussion

Hi Grace Marguerite Williams! How's it going?

Thank you for the question: "What is your opinion of a highly educated person who has a clerical or Mcjob? Do you believe that this highly educated person isn't so intelligent because h/she has a clerical or Mcjob?"

This question happens to be directly related to another one you pose. That one goes like this: "Do you judge how educated &/or how intelligent a person IS by what type of job h/she has?

You go on to say: "Peoples jobs oftentimes are a strong determinant as to their particular level of intelligence &/or education & people are judged accordingly. Doctors, lawyers, executives, & professionals are more highly esteemed than secretaries, waitstaff, & clerks. The former are viewed as more intelligent while the latter aren't."

Credential Inflation

The first stipulation to make is that I am confining my discussion to the United States of America. Although I'm sure that what I am about to say generalizes quite nicely, around the world --- the U.S.A. is what I know best; and the trends I'm going to talk about stand out in the sharpest relief in America.

As the late Godfather of Soul and "Hardest Working Man in Show Business," James Brown used to sing, "There Was A Time."

- There was a time when one did not have to even see the inside of a university or college, to become a school teacher. If you graduated high school, that was enough.

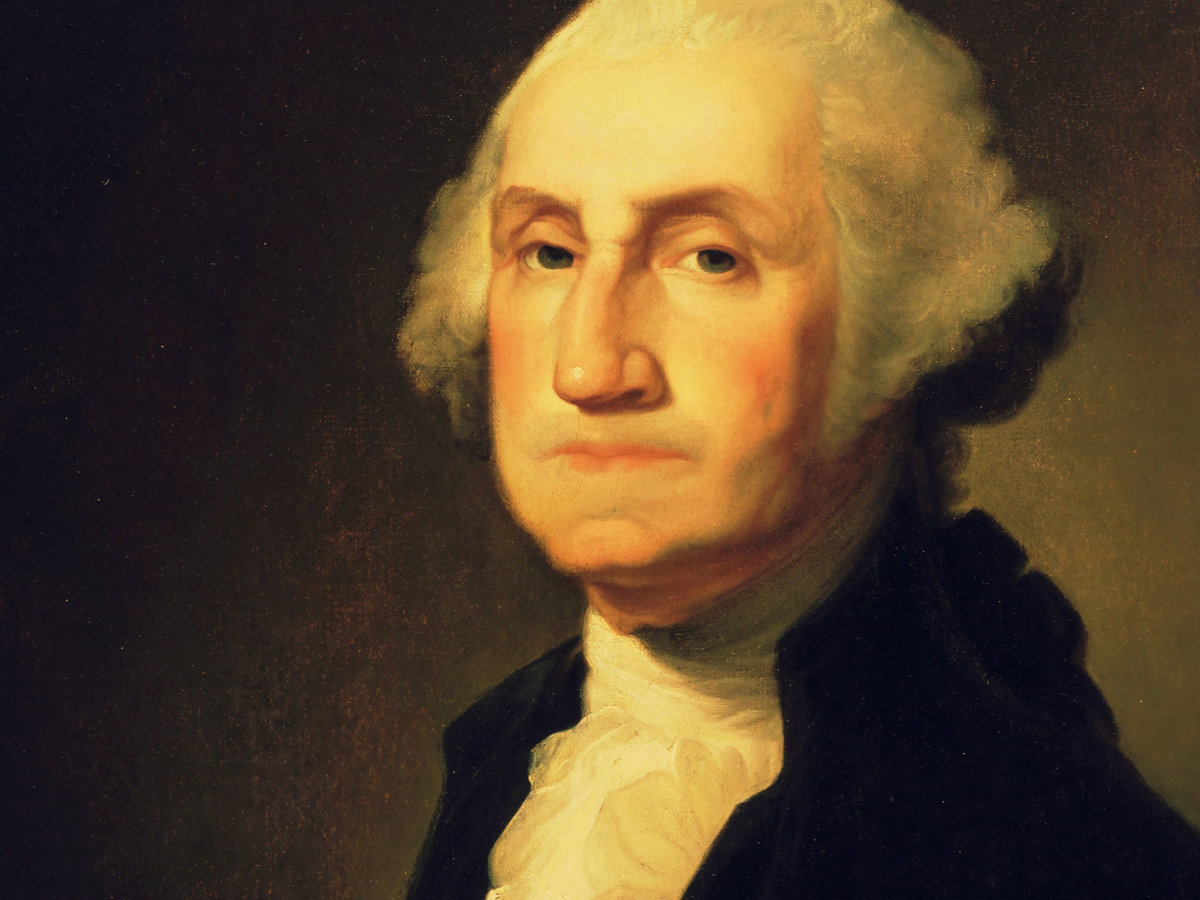

- The sixteenth President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, is an extreme example, you might say. He had, perhaps, a years worth of total schooling for his entire life, yet in addition to careers as a lawyer and Congressional Representative, before becoming President --- he was also a school teacher.

- But these days, parents feel cheated, if every single one of their children's teachers, in grade school, don't at least have a master's degree.

- There was a time when one did not have to even see the inside of a college or university, to be a reporter or "journalist."

- These days we have graduate schools of journalism; and it is hard to get a journalism job without that post-undergraduate "credential."

- There was a time when one did not have to even see the inside of a college or university in order to become a lawyer or "attorney." You didn't have to even see the inside of a high school, for that matter, to lean on the extreme example of Abraham Lincoln again. What you did was apprentice yourself to a practicing lawyer, learning from him; and then, when you were ready, you too the bar exam; and if you passed it, you were a lawyer.

More "There Was A Time"

Because of this process of "credential inflation," I'm talking about, certain jobs became, shall we say, for simplicity's sake, more fancy.

But it is also the case that certain other kinds of jobs, over this same period, became, shall we say, less fancy.

The "fanciness" I'm talking about pertains to perceived "intelligence" and "education" supposedly needed to do certain jobs.

Believe it or not, there was a time, in the United States of America, when manufacturing work was "intellectual," when it was "brain work," and, indeed, when it was "professional." But I don't want you to take my word for it. Let us turn to a more interesting source.

In an article titled, Education and the Structural Crisis of Capital: The US Case, professor of sociology, Dr. John Bellamy Foster tells us:

"In nineteenth-century capitalism, workers were in a position to retain within their own ranks the knowledge of how the work was done, and therefore exercised a considerable degree of control over the labor process. Hence, control of the labor process by owners and managers was often more formal than real. As corporations and their workforces and factories got bigger with the rise of monopoly capitalism, however, it became possible to extend the division of labor, and therefore to exercise greater top-down managerial control. This took the form of the new system of scientific management, or 'Taylorism,' within concentrated industry. Control of the conception of the labor process was systematically removed from the workers and monopolized by management. Henceforth, according to this managerial logic, workers were merely to execute commands from above, with their every movement governed down to the smallest detail" (1).

Here's where we are so far...

The twin forces of credential inflation and Taylorism, then, are what have made certain kinds of jobs "more fancy," fancier than they need to be; and that have made other kinds of jobs "less fancy." And, again, I have defined "fancy" as the perceived "intelligence" and "education" needed to do certain kinds of work.

Let's back up a little bit.

Here's what I'm saying: During the course of a nation's life, there is inflation of its currency, which makes goods and services more expensive in absolute terms, as the decades and generations roll by.

The other part of that is: As time goes by, as the decades and generations roll by, there is "credential inflation," which means more number of years of formal schooling, more advanced degrees and other kinds of formal certificates of expertise are needed to get hired to do certain kinds of work --- thereby putting this kind of work out of the reach of increasing numbers of people --- and, by the way, this is especially true for working people looking to advance their children up the socioeconomic ladder through education; one reason for this is the fact that the real wage, pay as related to the prices you have to pay for life's essentials, has remained either flat, or a little depressed since the late 1970s/early 1980s.

Why do we have "credential inflation"?

I credit a Trinidadian-Canadian professor of sociology, Dr. Anton Allahar, with having given a name to something that was right under our noses all along.

There is a talk he gave at a university, which you can watch on YouTube. It is not the one titled, "Why is the whole world not developed?," which is a taping of one of his classroom lectures; it is the other Anton Allahar YouTube video.

Professor Allahar's talk is about today's youth culture, specifically and primarily how it engages with higher education. Basically, the verdict of his cultural analysis is not very favorable, for various reasons. His resulting conception is that there are many, many youth entering college who should not be doing so; this is because their interests, talents, abilities, and inclinations to not point in the direction of a college or university liberal arts education.

One of the reasons he identifies for the stampede through the university doors is what he called "credential inflation." He gives a playful example: He talks about how one might come across an ad in the newspaper for someone to work for Block Buster Video; the applicant must have a BA degree.

Dr. Allahar correctly, facetiously, and rhetorically asks the question that goes something like: "Why do you need a BA degree to find the porno movies?"

The answer is quite simple. Dr. Allahar talks about the dearth of jobs, which causes kids to be "warehoused" in college longer, putting in more and more years, racking up paper credentials. When they come out---because the economy has finally managed to produce some jobs----they are not told that they are "overqualified" to work at Block Buster; instead "Block Buster" raises the "caliber" of employees its looking for (according to accumulated paper credentials).

Look, in 1950 parents would tell their children that the most important thing they could do for their future is get the high school diploma.

By 1980 four years of college was desirable; but one at least wanted to have an associate's degree --- you know, to ensure their future.

Today, the way many people talk --- today's bachelor's degree is yesterday's high school diploma. A bachelor's degree is considered practically the mandatory minimum in some quarters.

But a master's degree is really desirable. Who knows, perhaps in another ten years tomorrow's master's degree will be like today's baccalaureate.

And on and on it goes.

You know, many parents probably say to their children something like this: "Get your education because nobody can take your degree away from you."

Not to be a pessimist or anything, but the sad truth in the United States of America is: "They," or rather the system, does, in effect "take your degree away from you," by the attrition of credential inflation. Because....

- We do not have free college and university education as they do in other advanced industrialized countries like our. In England, for example, one goes to school, from preschool to the PhD., without their families ever having to pay a dime "out-of-pocket."

- This means that not every family, in the United States of America, can endure the inflation the same way, and finance their kids evermore accumulation of paper credentials.

There is a second way in which "it' can be "taken away from you."

What is that way?

You know what? I'll let economist Dean Baker explain it. I would refer you to his excellent book, free online, called: "The Conservative Nanny State: How the Wealthy Use the Government to Stay Rich and Get Richer."

You want to read Chapter One: Doctors and Dishwashers -- How the Nanny State Creates Good Jobs for Those at the Top. The very title tells you a lot, doesn't it?

Let's start at the first paragraph of the chapter, for some important background. We read:

"From 1980 to 2005 the economy grew by more than 120 percent. Productivity, the amount of goods and services produced in an average hour of work, rose by almost 70 percent. Yet the wage for a typical worker changed little over this period, after adjusting for inflation. Furthermore, workers had far less security at the end of this period than at the beginning, as access to health insurance and pension coverage dwindled, and layoffs and downsizing became standard practices. In short, most workers saw few gains from a quarter century of economic growth" (2).

How come?

Before we get to the "how come?," let's ask Dr. Baker to describe the other half of the picture.

Dr. Dean Baker, would you describe the other half of the picture for us, please?

Why certainly! Chapter One continues:

"But the last 25 years have not been bad news for everyone. Workers with college degrees, and especially workers with advanced degrees like doctors, lawyers, and accountants, have fared quite well over this period. These workers have experienced large gains in wages and living standards since 1980. The wage for a worker at the cutoff for the top 5 percent of wage-earners rose by more than 40 percent between 1980 and 2001. Those at the cutoff for the top 1.0 percent saw their wages increase by almost 75 percent over this period. The average doctor in the country now earns more than $180,000 a year. A minimum wage earner has to put in 2 days of work to pay for an hour of his doctor's time. (After adding in the overhead fees for operating the doctor's office, the minimum wage earner would have to work even longer)" (3).

One more thing before we get to the "how come." We need to look at political justification.

Still quoting from Chapter One, Dean Baker writes:

"While doctors, lawyers, and accountants don't pull down the same money as corporate CEOs, or Bill Gates types, their success is hugely important in sustaining the conservative nanny state. If the only people doing well in the current economy were a tiny strata of super-rich corporate heads and high-tech entrepreneurs, there would be little political support for sustaining the system. Since the list of winners also includes the most educated members of society, it creates a much more sustainable system. In addition to being a much broader segment of the population (5-10 percent as opposed to 0.5 percent), this group of highly educated workers includes the people who write news stories and editorial columns, teach college classes, and shape much of what passes for political debate in the country" (4).

Let's do "how come?" now.

Dr. Dean Baker: "It doesn't take sophisticated economics to understand how some professionals have fared well in recent decades, even as most workers have done poorly; its a simple story of supply and demand. The rules of the nanny state are structured to increase the supply of less skilled labor, while restricting the supply of some types of highly skilled professionals. With more supply, wages fall --- the situation of less-skilled workers. With less supply, wages rise --- the situation of highly skilled professionals" (5).

That is the basic story. For an example of how the US federal government implements this policy, check this out:

In 1997, the doctors section of the US professional class got something of a scare. It seems that, according to the "American Medical Association and other doctors' organizations," there was an "inflow of foreign doctors" that "was driving down their salaries" (6).

Small footnote: Dr. Dean Baker tells us that if we, in the United States, paid doctors what they make in Western Europe---never mind some place like Trinidad or Nicaragua---"the savings would come close to $100,000 per doctor, approximately $80 billion a year. This is ten times as large as standard estimates of the gains from NAFTA" (7).

Now then, in response to the emergency faced by US doctors in 1997, "Congress tightened the licensing rules for foreign doctors entering the country[.]" The result of this was that "the number of foreign medical residents allowed to enter the country each year was cut in half" (8).

Dr. Baker elaborates on the point:

"The most important set of barriers is state specific licensing, which involves distinct and idiosyncratic rules for working in professions like medicine, dentistry, and law. If the United States were committed to free trade in high-paying professions, it would negotiate trade agreements that established international standards in these professions. These standards would be based on recognized health and quality standards, as is the case for consumer safety regulations on manufactured goods under the WTO" (9).

There is one last quote and this one is powerful:

"Just as no one will build a factory in China to export steel to the United States until they know they will not be obstructed by tariff or quota barriers, no one will design a university curriculum around training students to work as professionals in the United States unless they know that their graduates will have this opportunity" (10).

I would encourage you to check out these sources, and others, for yourselves. But please know this: The next time you take a cab; and the gentleman behind the wheel, from Trinidad, tells you that he had been a physician in his home country, believe him. You see, the reason that Caribbean gentleman has been driving a cab for the past ten years, or so, is precisely because of the process I have all too briefly outlined above.

Let's back up and slow down a little

What I'm saying about "state specific" licensing may throw you because of the phraseology. Take the law. You know that to take the bar, pass it in Connecticut, and get licensed in Connecticut, is not the same as being licensed to practice law in Rhode Island, New York, or Arkansas. You know that, right?

It is the same for medicine. To have a license to "practice medicine" in Arizona is not the same as being licensed to do so in California, Maryland, or Alaska.

That's for a native-born American citizen. Imagine how confusing it would be for someone from another country intending to make his home in the United States, and not knowing exactly what state of the Union he intends to settle himself and his family.

You know what I mean, right? In theory, "the law is the law." But as you know, state legislatures do their own thing in certain areas; and you come to a place where what is acceptable and legal in one state, may not be acceptable and legal in another state.

It is the same thing with medicine in the United States. "Science is science" right? But you know its not so simple as that. Certain medical procedures that are allowable in one state, may not be legally permitted in another state.

As you know, Mrs. Williams, the United States of America is extremely influenced by a powerful fundamentalist religion sector, concentrated in the southeastern region of the country; and this has effects upon public policy. For all we know, it may even be the case that what is legally acceptable as medical science in one state, may not be, and so on and so forth.

Anyway, that is the second way "they" can, somewhat "take it"---the college degree---"away from you"----if you are an immigrant to the United States.

There's more I could say about this, but let's move on to something else. After all, there are other reasons why "intelligent," "highly educated" people end up doing clerical and "Mcjobs" in the United States.

Grade Inflation at America's Institutions of Higher Learning

An ongoing, open-sore scandal going on in the United States of America is rampant grade inflation (11). I have just referred you to a newspaper article on the subject, but, of course, you can simply Google the words "America. Grade inflation. Colleges," or something like that and get reams of results.

Incidentally, my understanding is that this practice has roots going back to the 1960s, as the Vietnam War was going on; and colleges and universities sought to keep their kids from failing, thus losing their student deferment status, and thus being drafted into participation in the war (12).

I would also refer you to a very interesting article by a very interesting conservative political philosopher called Ross Douthat. The article he published for The Atlantic magazine is titled "The Truth About Harvard" (13).

By the way, you may recall there was one year, a while back, when ninety percent of Harvard's graduating class were awarded "honors."

Anyway, Mr. Douthat's article is about his personal experience at Harvard. What he's saying is basically this: It is hard to get into Harvard; but once you are in, it is way easier than it should be to get through---on the undergraduate level.

Let's look at a couple of the most powerful and meaningful passages from his very powerful and meaningful article --- where he talks about what he sees as the roots of grade inflation, reflective of what he calls the "the overall ease and lack of seriousness in Harvard's undergraduate academic culture."

We read toward the end:

"Mostly I logged the necessary hours in the library and exam rooms, earned my solid (if inflated) GPA and my diploma, and used the rest of the time to keep up with my classmates in our ongoing race to the top of America (and the world). It was only afterward, when the perpetual motion of undergraduate life was behind me, that I looked back and felt cheated.

"Afterward, too, I began chuckling inwardly when some older person, upon discovering my Harvard affiliation, would nod gravely and ask, But wasn't it such hard work?

"It was---but not in the way the questioner meant. It was hard work to get into Harvard, and then it was hard work competing for offices and honors and extracurriculars with thousands of brilliant and driven young people; hard work keeping our heads in the swirling social world; hard work fighting for law-school slots and investment banking jobs as college wound to a close... yes, all of that was heavy sledding. But the academics---the academics were another story" (14).

I recommend a careful reading of Mr. Douthat's article.

Here's the point: There is rampant grade inflation at America's institutions of higher learning; and, unfortunately, this tends to work to the disadvantage of minority graduates.

Why is that?

Because, as a 2002 USA Today editorial put it:

"When all students receive high marks, graduate schools and business recruiters simply start ignoring the grades. That leads the graduate schools to rely more on entrance tests. It prompts corporate recruiters to depend on a 'good old boy/girl' network in an effort to unearth the difference between who looks good on paper and who is actually good.

"Put to disadvantage in that system are students who traditionally don't test as well or lack connections. In many cases, those are poor and minority students who are the first in their families to graduate from college. No matter how hard, their As look ordinary.

"Viewed in that light, the fact that 50% of all Harvard students now get As is a troubling problem" (15).

It seems to me that what I've just talked about above goes a long way to explaining the following:

- That according to the Federal Glass Ceiling Commission, whites in America, hold over 90 percent of all management-level jobs in the country; receive 94 percent of all government contract dollars; and hold 90 percent of all tenured faulty positions on college campuses in the country (16).

- That according to data collected by the Department of Labor, white men with only a high school diploma are more likely to have a job than blacks and Latino men with college degrees (17).

- Which, in turn, helps to at least partially explain how it is that whites have an unemployment rate that is half that of blacks; and poverty rates one-third as high for blacks and Latinos (18).

- Which, in turn, along with housing discrimination (19), helps to at least partially explain why whites have an average of 11 times the wealth as blacks; and 8 times that of Hispanics (20).

- And speaking of average family wealth, this also has a profound effect on the kind of schools you can attend, before college, and the kind of education you can get from them---due to the way the public school system is funded in the US, which is through property taxes on land, homes, and businesses. The differences between affluent neighborhoods and poor communities are startlingly "savage," both across school districts and even within individual schools, quite consistent with race and class demographics (21).

Thank you for reading!

References

1. Foster, Bellamy, J. (2011, July-August). Education and the Structural Crisis of Capital: The US Case. Retrieved June 28, 2016

2. Baker, D. (2006). The Conservative Nanny State: How the Wealthy Use the Government to Stay Rich and Get Richer. Chapter One: Doctors and Dishwashers --- How the Nanny State Creates Good Jobs for Those at the Top. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

3. ibid

4. ibid

5. ibid, section: The Basic Conservative Nanny State Mythology.

6. ibid

7. ibid

8. ibid

9. ibid

10. ibid

11. Slavov, S. (2013, December 26). How to Fix College Grade Inflation: Inflated grades are a serious problem, but there are ways to fix them. Retrieved June 30, 2016. (U.S. News & World Report).

12. Newlon, C. (2013, November 21). College Grade Inflation: Does 'A' Stand For Average? Retrieved June 30, 2016. (USA Today)

13. Douthat, R. (2005, March). The Truth About Harvard. Retrieved June 30, 2016. (The Atlantic).

14. ibid

15. (2002, February 7). Ivy League Grade Inflation. (editorial/opinion. USA Today). Retrieved June 30, 2016.

16. Wise, Tim. Speaking Treason Fluently: Anti-Racist Reflections From An Angry White Male. Soft Skull Press, 2008. (paperback). 186

17. ibid

18. ibid, 193-194

19. ibid, 239-240

20. ibid, 193

21. see Kozol, Jonathan. Savage Inequalities: Children In America's Schools. Broadway Books, 1991. (paperback).