Does God Exist? Ask a Cognitive Scientist

There are numerous faiths scattered across each continent of the Earth, and a veritable necropolis of religions that have perished in the course of human history. Each has its own rituals and doctrines, and each makes an intransigent claim to be the paladin of truth. United under the common genus, religion, we find that each requires belief in supernatural beings. From Zeus to Allah there are thousands of deities littering the human timeline, bubbling into prominence before descending into obscurity. Such avid acceptance of contradictory faiths elucidates a remarkable facet of the human condition: we have a propensity for inventing gods.

To explore our fervor for the divine, we must understand how the mind works, and this can only be achieved with novel experiments exploring human psychology. In this article I will review the work of cognitive scientists who have investigated our proclivity for piety, yielding results that will shock theists and atheists alike. In doing so, some have made the greatest sacrifice; for in explaining the falsity of these myriad impostor religions, they inadvertently tarnish the credibility of the one they hold dear.

Intuition and Recollection

All humans perceive the world in an intuitive way. We possess a folk biology, which identifies beings that live, die and require sustenance as agents that may be dangerous or useful to us. We have folk mechanics, which tells us that solid objects cannot occupy the same space and dropped objects fall to the ground. We possess folk psychology, or the knowledge that other beings have desires, beliefs and intentions that are separate from our own. We are born with these intuitions, and they play a fundamental part in the way we perceive the world.

Any event that violates intuitive expectations is likely to garner our attention. When we read a story about a talking tree, it is more likely to be remembered than a tree that doesn't talk. Similarly, a narrative about an ethereal, eternal, omnipresent and omnipotent God is going to violate our folk biology, mechanics and psychology. We’re attracted to the narrative because the God is perceived to be an incredibly dangerous or useful being. It may possess strategic information about what’s in our mind or the minds of others. To protect or gain this knowledge and to avoid personal jeopardy, it is paramount that we learn about the God, even if its existence appears implausible. Pascal Boyer identified this attraction to the divine in his book Religion Explained.

Humans are pre-wired to absorb anything that is counter-intuitive, including gods, but this doesn’t include every wild creation of the imagination. Gods still think and act like humans; they create things they cannot reverse, they have beliefs about what is good and evil, they have plans for the future, and they communicate with people. The attribution of counter-intuitive abilities such as telepathy is what makes them memorable. Cognitive scientists have shown that counter-intuitive information must be embedded in intuitive factual information for it to be memorable. For example, in John 21:6, when Jesus auspiciously instructed his disciples to cast their nets on the other side of their boat, it was within the context of a fishing trip involving the usual travails of acquiring a catch. If Jesus created fish out of thin air and beamed them into the boat then it wouldn’t be such a memorable story. Scott Atran’s work, In God’s We Trust, illustrates this finding in greater detail.

The attractiveness of particular stories and how they spread through a culture is called the epidemiology of representations. Unlike Richard Dawkin’s memetic theory, stories are transformed based on information already held in an individual’s mind. The most successful stories are those which appeal to our evolved biases for absorbing particular information. The seminal work on this topic is Explaining Culture by Dan Sperber. The ability to absorb information about gods is called a memory cognitive bias. However, this bias does not explain why we create stories about gods in the first place.

Creating Gods

Conjuring up a being in the abyss seems like the domain of science fiction, but it is something we do every day. We give our cars and boats names, we talk of gremlins in our machines, and we chide lady luck for our misfortunes. Like our cognitive bias for remembering counter-intuitive information, we have a bias for attributing agency to events that show signs of being controlled by some force. It would be foolish not to be biased in this way, because if an event looks like it is being controlled by another being, then it is far better to err on the side of caution than to end up being eaten! The costs of not attributing agency are so severe that natural selection has given humans a hyper-active agency detector that blames many events on non-existent beings.

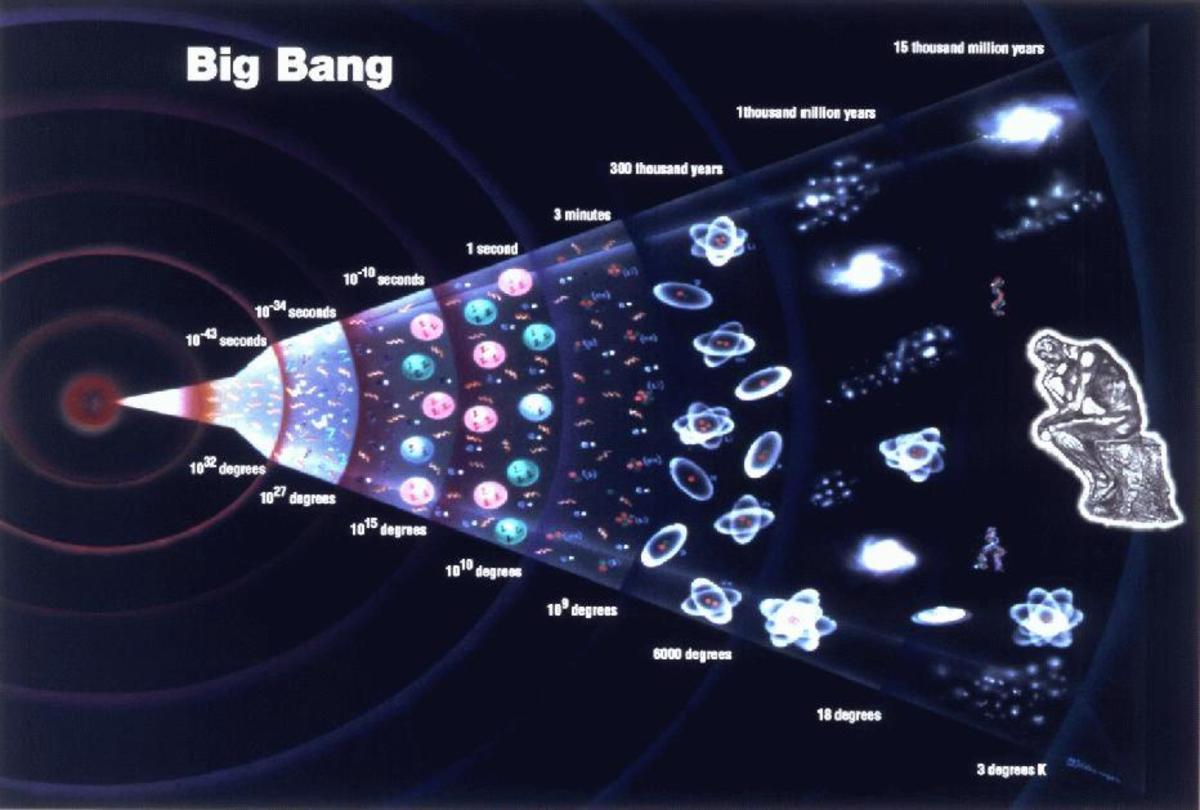

A number of events meet the criteria for agency. Extreme bad luck may be seen as unlikely to occur without some intentioned malevolent being. Events such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, floods, and hurricanes are all rare occurrences of terrible bad luck. The sun’s movement across the sky or the tides rising on the beach are examples of events that show signs of a goal-oriented controlling force. These events require beings powerful enough to perform them. Thus, stories are created about powerful gods, and our bias for absorbing these stories guarantees they will be popular.

Why Believe?

Many of us don’t believe religious stories when we hear them, but we still remember them. Perhaps some of us believe the stories because we encounter them when we are very young. Richard Dawkins has described childhood religion as a suspension of disbelief, which basically means children don’t have enough knowledge to properly evaluate the story, so they put it in a box marked “maybe” and let it fester. The testimony of authority figures such as parents and priests will constitute evidence for the story being true, improving the chances of the child forming a belief.

Nevertheless, different children will respond differently to testimony, suggesting the presence of another factor that affects belief formation. Furthermore, why do some adults turn to religion? It is apparent that many people become religious during times of stress and anxiety. This anxiety emerges from threatening events such as near-death experiences, illness, catastrophe, grief, pain, drug withdrawal, prison, or financial difficulty.

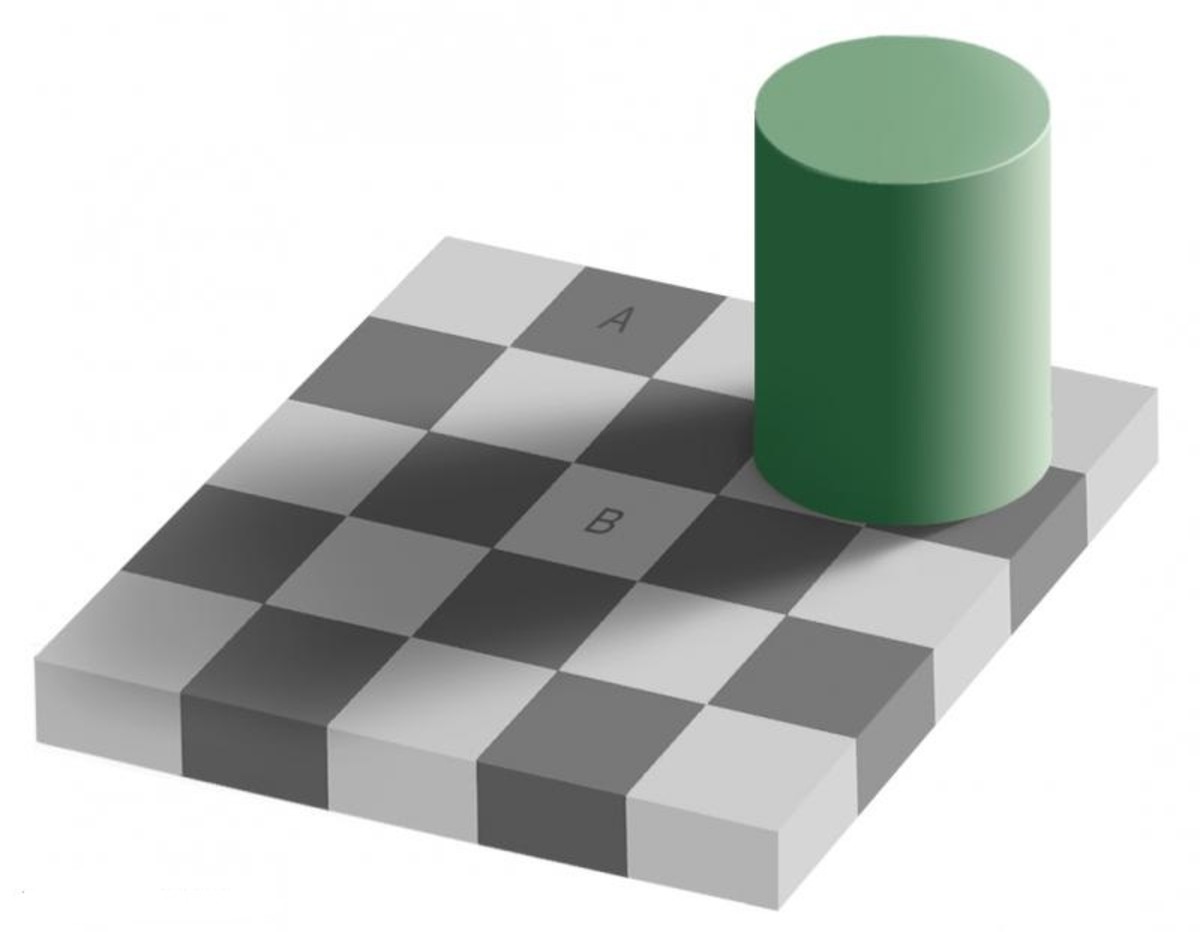

It is likely that anxiety reduces the scrutiny we apply to comforting propositions, such as the existence of an afterlife or God. Recent evidence partially confirms this theory by indicating the presence of another cognitive bias called the optimism bias. When presented with information that is better than our expectations, we are far more likely to adjust our beliefs than when we are presented with information that is worse than expectations. We appear to filter out bad information as a means of reducing stress and anxiety. Indeed, depressed individuals lack an optimism bias, suggesting a clear link between anxiety reduction and the acceptance of comforting beliefs.

Forming a belief in this way guarantees it will be staunchly defended against arguments that threaten it. This is known as confirmation bias.

Summary

The question of God’s existence is as unanswerable as the existence of an invisible elephant hiding behind Pluto; but the question of why people believe in God is open to the scrutiny of science. More research is needed, but it is clear that the cognitive science of religion may soon explain why we believe in God by illustrating the emotional condition of those most susceptible to becoming faithful. With a depiction of the processes that lead to our theistic beliefs it is possible that many people will abandon their faith. Regardless of atheistic motivations, what is most important is that we have what is needed to make an informed decision about what to believe.