Ancient Gnosticism and Modern Evangelicalism (a comparative piece)

Introduction

(For ease of reading I have opted to use the present tense in referring to both traditions, although Gnosticism is ancient. Changing tenses multiple times within sentences proved quite burdensome)

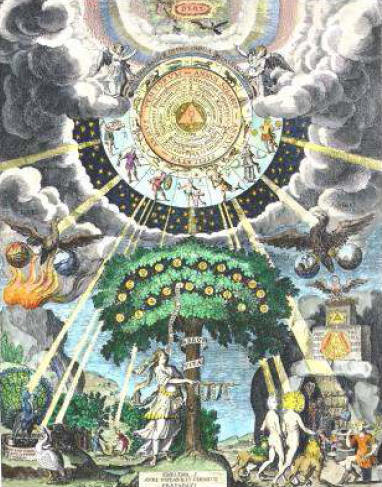

Lots of material has been published on the subjects of ancient Gnosticism and contemporary Evangelicalism separately, but few authors have attempted a comparison of these two strands of Christian (and to a certain extent, pseudo-Christian) belief and practice. Harold Bloom, in his book The American Religion, compares these historically displaced Christian movements, however, he is prone to over-exaggeration and harbors an incorrect definition of “gnosticism”. In order to delve deeper into the similarities between the Evangelical and Gnostic ideologies, the broad categories of worldview and practice will be considered in turn. Despite their initial differences, upon careful scrutiny one can notice many analogous characteristics in both group’s view of the world. For example, both systems are rather exclusive, and define themselves as a kind of elite, set apart from other so-called “Christians”. This mentality, consequently, gives rise to dualistic views of anthropology, society, and cosmology, and leads to negative conceptions of “the world”. Logically, the fallen, corrupt, and degenerate character of “this world” would conversely elevate and emphasize the soteriological function of the savior figure, which is present in both Gnosticism and Evangelicalism. Additionally, both Gnosticism and Evangelicalism were highly influenced by the intellectual currents of their time, the former containing many Platonic characteristics, and the latter appropriating lots of psychological jargon and appealing to common American aspirations. Finally, both belief systems have a certain mythologizing tendency, which allows them to derive unique material from scripture and extra-biblical sources.

On the level of practice, the most obvious and central similarity is the centrality of a mystical kind of conversion experience. This overwhelming importance placed on religious experience tends to displace and remove the importance of creeds and historical teachings. Consequently, in both religious systems, spiritual practice becomes highly individualized. Additionally, the role and importance of traditional sacraments are reduced, and in some instances replaced by others, in order to better accommodate their own, new, religious proclivities. Finally, both Evangelicalism and Gnosticism place heavy importance on morality and personal conduct, leading both groups to conclude that perfection must be sought for, and is indeed attainable in, this life.

The Phenomenon of the “In-Group”

Dualisms

Both Gnosticism and Evangelicalism tend to view the world and humanity in dualistic terms. As clear in the above example, for certain Evangelicals, anthropogony itself breeds two kinds of individuals, those who would be saved, and those who would be damned. Similarly, Gnosticism, most characteristically the Sethian variety, posits a very similar anthropological structure. Seth, having inherited the seed of the pneuma from his father Adam, was the only individual who had the ability to transmit the germ of salvation to his offspring; all others, who were descended from Cain, Abel, or anyone else, were doomed to an unenlightened existence due to the fact that no part of the fractured Pleroma lay within them (Layton 47). Obviously, the Sethian Gnostics identified themselves as the descendents of Seth, and, like the above-described Evangelicals, would be the only ones to receive salvation. Dualism does not cease at the anthropological level, however, for it extends to society and the world itself. One of the most basic tenets of Gnosticism is the difference between the heavenly abode of the Unknown Father and material existence, which is often described as the bastard child or abortion of Sophia and the Demiurge. Indeed, the very tripartite division of humanity reflects the gnostic distaste for matter, for they, the Gnostics, are “pneumatics” belonging, ultimately, to the heavenly realm, where the lowest of peoples are the “fleshy”, who revel in, and are solely composed of, crude matter (in Greek, hyle). Interestingly, the plight of the gnostic, as one who is a prisoner in an alien realm, is nicely summed up by a favorite saying of Evangelicals: “in the world, but not of the world.” This simple statement belies the Evangelical movement’s own distaste for, and indeed distance from, the world. Pastors can be heard saying such things as: “‘in living for Christ today you have to go against the world’” (Balmer 16). Furthermore, Balmer demonstrates that “the 1925 Scopes Trial convinced fundamentalists that the broader American culture had turned hostile to their interests…” (95). Thus, “fundamentalists have busied themselves devising various institutions to insulate themselves and their children from the depredations of the world. (In fact the terms worldly and worldliness…are often spoken sneeringly, in a tone at the same time condescending and cautionary)” (95). According to the Evangelical worldview the Bible and Jesus Himself stand in opposition to liberalism, immorality, homosexuality, “modernism,” and everything in “the world” for it is corrupt and without hope of salvation. Thus, both Gnostics and Evangelicals tend to eschew material existence and society, the former because of ontologically different existential values and the negativity inherent in materiality, and the former because of the world’s degradation and hostility to what they perceive to be Christian. This sentiment is quintessentially contained in the doctrine of pre-millennialism. As “evangelist Dwight L. Moody, a pre-millennialist, said in 1877…‘I don’t find any place where God says the world is to grow better and better…I find that the earth is to grow worse and worse, and that at length there is going to be a separation’” (35). This rejection of the world and negation of the belief that humans can better society is very similar to the denunciation of matter and the emphasis on personal salvation of the ancient Gnostics. Both religious sects probably inherited this dualism from a common source, that of Jewish apocalypticism, as posited by Rudolph (if you are interested in apocalypticism, please read some of my other Hubs). Although Gnostic salvation is primarily vertical (in that it requires the ascent and return of the pneumatic spark to the Pleroma) and Evangelical salvation is mostly horizontal (in waiting for the Second Coming), both groups have a “dualistic-pessimistic world view [in which] the present age is bound to perish and will be followed by the future age of redemption” (278). Likewise, similar to apocalyptic Judaism, heavy influence is placed on the figure of the savior or messiah in both systems.

The Savior

The corrupt state of the world in which the faithful reside makes even more profound and central the salvific role of the savior. As Rudolph states, “only the act of knowledge and the help of the redeemer can deliver [the gnostic]…[T]his is the great theme of gnostic soteriology…” (111). Indeed, “Gnosis is a religion of redemption”, wherein “salvation is no longer primarily sought in this world, as was the case with most of the ancient cultic religions…but in another, eternal, spiritualized world in which the change and anxiety of this world are forgotten” (113 + 287). Likewise, the role of Jesus as the harbinger of God’s grace is central to Evangelicalism. As Balmer points out, both “Martin Luther and John Calvin…insisted that we all inherit Adam’s sin and that only the grace of God, mediated through Jesus Christ, delivers us from the condemnation we so richly deserve. We can do nothing, they insisted, to earn our salvation; God, in His inscrutable wisdom and mercy, has chosen to rescue us from the squalor of our sinfulness regardless of our merit” (239). Indeed, the role of Jesus has become even more central to Evangelical thought in recent years, almost supplanting the role of God the Father, and bringing about the criticism that Evangelicals eschew the concept of the Trinity, and are thus not Christians in the historical sense. Some Evangelical groups engage in apologetics in defense of their beliefs, while others simply lump the concept of the Trinity in with other “heresies” the historical Christian Church invented. As Bloom indicates, “though Assemblies of God theology is officially Trinitarian, in praxis the Pentecostal knows only Oneness, and calls the Holy Spirit by the name of Jesus, not the Jesus of the Gospels or even the Christ of Paul…” (177). Regardless of whether or not this statement is true or hyperbole there definitely exists a strong emphasis on the role of Jesus in most American Evangelical circles. For “this Jesus [comes] to one, of his own will, and not the sinner’s…Preachers [can] prepare the sinner’s heart, but only Jesus [is] truly [able to] begin the process of salvation” (65). The actual act of conversion/salvation, which the Savior imparts, will be dealt with later, however, it should be clear that both the savior and the act of salvation play central roles in Gnosticism and Evangelicalism.

Intellectual Influences of the Times

While some religious systems preserve worldviews in opposition to the contemporary, sometimes secular, mindset, both Gnosticism and Evangelicalism tend to appropriate rhetoric and concepts from outside the confines of their traditions, despite their official opposition to the outside world and other groups. In the context of Gnosticism, the most obvious influence was Greek philosophy. As Rudolph recognizes, “the vocabulary of most of the gnostic systems, even the apparently most ancient, [is] derived from the conceptual language of Greek philosophy” (284). Many early gnostic leaders, probably the most prominent of whom was Valentinus, were admittedly Platonic scholars, and great ones at that. The connection between Platonism and Gnosticism is more firmly established when one considers Albinus’s Timaeus and the writings of Plotinus. The first is a cosmogonic myth, whose creative structure of successive emanations greatly resembles the gnostic myth of origins; the second attempts to refute the tenets of Gnosticism on the philosophical level. Indeed, Plotinus does not consider Gnostics to be Christians, but instead bad philosophers who “do well to borrow…ideas from Plato if they understand them clearly…But…should not seek to establish their own doctrines in the minds of their followers by affronting and insulting the Greeks” (78-9). Plotinus also criticizes them for “compos[ing] magical incantations and address[ing] them to the beings above…” (92). However, Rudolph states that “the gnostics are not an unusual phenomenon in this respect, but are firmly rooted in the contemporary scene in which the practice of sorcery, astrology and numerical speculation – in addition to philosophical eclecticism – was not a rarity…” (209). Evangelicals, too, despite their outward hatred for “the world,” paradoxically affirm its fruits. As Bloom only mentions briefly, psychology plays a crucial role in Evangelicalism, especially in the guise of “positive thinking” (65). “Recovery theology,” too, assimilates psychological jargon, and emphasizes the overcoming of addictions and personal problems. Jesus, here, appears more as a psychoanalyst or twelve-step leader, than a sacrificial lamb. Perhaps most baffling is the existence of “prosperity theology,” which states that God wants people to be rich and that He rewards the faithful with money. This obvious allusion to, and promise to fulfill, the capitalist American dream seems very out of place in a system that claims to “despise the world.” This tendency towards religious innovation is something unique to both Gnosticism and Evangelicalism, allowing both to utilize various myths and material absent from scripture and tradition.

Myth-Making and Extra-Biblical Material

Both Gnostics and Evangelicals are, to a certain extent, religious innovators who seek to legitimize their experiences through creative interpretations and extrapolations of scripture and contemporary ideas. To delve into the sea of material regarding this topic as pertaining to Gnosticism would be nigh impossible, but certain aspects must be identified and highlighted. Rudolph claims that gnostic interpretations of scripture would take “a statement of the text [and give it] a deeper meaning, or even several, in order to claim it for one’s own doctrine or to display its inner richness. This method of exegesis is in Gnosis a chief means of producing one’s own ideas under the cloak of the older literature – above all the sacred and canonical” (54). Likewise, Gnosticism tended to “draw its material from the most varied existing traditions, attach itself to it, and at the same time set it in a new frame by which this material took on a new character and a completely new significance” (54). This technique allowed them to appropriate Platonic concepts and frame them in a new way, as is clear in the Apocryphon of John. Likewise, Gnostics interpreted the Hebrew Bible in a radically novel fashion. To the Gnostic, the serpent in the Garden was a messenger from the highest God, trying to help Adam and Eve escape the clutches of the Demiurge; the Biblical Flood was an attempt on behalf of the Demiurge and the archons to kill those who had the spark within them, as was the case again with the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah (136 + 138). Indeed, all of Gnostic theology can be regarded as an imaginative re-interpretation of the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, Christian theology, and Greek philosophy. Like the Gnostics, Evangelicals have arrived at some very interesting insights as well. Despite the fundamentalist insistence that the Bible can only be interpreted in one way (and, surprisingly, that single way is their way), many unique doctrines have been produced from both fundamentalist and charismatic camps. Firstly, most importantly, and most universally, all Evangelicals agree on the inerrancy of Scripture. The concept of “sola scriptura, reliance on the Scriptures only, became a bulwark of the Protestant Reformation”, and probably catalyzed these doctrinal innovations (Balmer 194). Interestingly, however, nowhere in the Bible does it state that the words contained within are inerrant, flawless, unchangeable, and immune to the variety of interpretations resulting from the process of translation. This is, indeed, the most central and cherished of Evangelical “myths,” if it can indeed be called such. The inerrant Bible’s importance is so central “that detractors have accused evangelicals of bibliolatry: elevating the Bible to the status of an idol that is itself worshipped” (195). As strange as this claim sounds, the Bible is employed in strange ways, oftentimes utilized as a kind of magical talisman by preachers as they pound on it or wave it in the air during some of their more lively sermons. Harold Bloom reveals the Southern Baptist fascination with the Bible when he cites this statement of a practitioner: “you get the idea that the Bible is yours, personally, and not external to you as with Luther’s sacraments. The Bible is internal to you with the Holy Spirit” (203-4). This mystical conception of “the interior bible” is not to be found anywhere in scripture, instead it is an extra-biblical belief, central to Southern Baptist spirituality. Perhaps more akin to the Gnostic tendency to “mythologize,” and indeed closely related to Jewish apocalypticism, is the Evangelical doctrine of dispensationalism “that insists that all of human history could be divided into ages or dispensations” (130). Here, “the notion of successive covenants, a distinctive characteristic of dispensational theology, asserts that God has adopted different strategies for dealing with humanity through the successive dispensations” (40). This belief, purely spawned by interpretations attempting to make sense of the Bible, most resembles an Evangelical “myth of origins” or “mythic history.” Likewise, pre-millennialism (the belief that the world will get more and more corrupt until the coming of Jesus, who will then gather the faithful and judge the world) and post-millennialism (the belief that emphasized the Social Gospel in claiming that humans are to better society and the world to the point of perfection, at which time Jesus will reign as King) can also be correctly considered Evangelical myths. Less mainstream, but certainly visible, are the charismatic leaders, who believe they receive revelations directly from God. Curtis Frisby of The Capstone Cathedral in Phoenix, Arizona, goes even as far as to add his own literature and divinely inspired information to the corpus of sacred writings (80). Interestingly then, despite Evangelicalism’s outward insistence on the inerrancy of the Bible and the plainest, most obvious interpretation thereof, it, like ancient Gnosticism, develops its own set of myths and beliefs either from scripture, personal inspiration, or extra-biblical material.

The Experiential Dimension

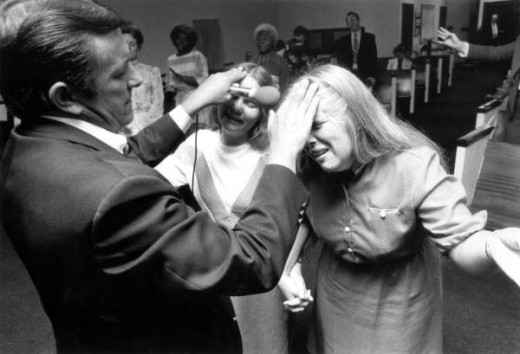

This is the most obvious and central similarity between Evangelicalism and Gnosticism. Both religious systems are primarily concerned with what Bentley Layton terms “gnosis or acquaintance” with God (9). For the Gnostic, the wayward soul is finally “united in the bridal chamber…and so attains her rebirth, a process which is interpreted as ‘resurrection’…” (Rudolph 110). During this process, “the redeeming knowledge which the redeemer imparts is an esoteric possession for the elect, and cannot be known by the evil powers of the world, since it belongs to another and ‘alien’ world” (148). Again, the reader is reminded of the Evangelical saying “in the world, but not of the world.” The salvific process for the Evangelical is almost identical with that found in Gnosis. For the Evangelical, the moment of “acquaintance” with God (or being “born again”) results in the knowledge that he/she has been saved, and grants him/her membership in the exclusive group of the elect (the Evangelical community). This palpable experience of forgiveness and salvation is what is most centrally sought in Evangelicalism. Here, the “acceptance of salvation through gnosis (acquaintance) of the savior” is datable, and constitutes a turning point in the Evangelical’s life (Layton 220). As Bloom states it, “conversion, or ‘getting saved’ or ‘being born again,’ is the frantic center of [their] spiritual life and is wholly inward” (204). Here, as in Gnosticism, the distance between God and man is drastically collapsed, and, in a way, eradicated, for the saved “achieves the image of God in himself through God’s grace” (217). This “internal resurrection” is often considered a “‘second blessing’” or baptism, in which “‘inbred sin’” is “eradicated” (Balmer 227). The centrality of this experience, however, has consequences for both the Gnostic and Evangelical systems, for, as so often is the case, when religious experience is of central importance, doctrine and tradition often fall by the wayside.

Lack of Cohesive Tradition and Historical Consistency

Religious systems that focus on personal experience tend to change more rapidly than those focused on creed and tradition. Because each individual’s experience is considered wholly sacred and legitimate, new innovations, interpretations, and personal preferences take precedence over historical teachings. As Rudolph indicates, “there was no gnostic ‘church’ or normative theology, no gnostic rule of faith nor any dogma of exclusive importance. No limits were set to free representation and theological speculation so far as they lay within the framework of the gnostic view of the world” (53). For the Church Fathers, the primary opponents of Gnosticism, this was clear evidence that the Gnostics were a group foreign to Christianity. Likewise, their refusal to ascribe to “official” doctrine and creed, or acceptance and allegorical interpretation thereof, upset the Church Fathers. Hence, they often complained about the lack of a cohesive and congruent Gnostic belief system, for divergences in matters of faith existed not only between different Gnostic schools, but between teachers and disciples as well, which, obviously, was due to the more free attitude of Gnosticism in regards to official teachings and personal experience. Instead of fretting about these issues, however, Gnostics enjoyed the diversity of their religious convictions, believing that because pieces of their worldview could be found in all religions they were practicing something akin to a “primordial tradition,” or we might call “perennial philosophy.” Evangelicals, like the Gnostics, tend not to emphasize the teachings of their founders. For example, “Calvin, along with Martin Luther…insisted that sinners could do nothing to earn forgiveness; salvation was the gift of God, available by grace, through faith” (Balmer 304-5). This predestinarianism, however, does not agree well with American sensibilities of personal agency and individual achievement. Thus, such concepts are almost never discussed in Evangelical circles, and instead a very rigid morality and strict belief system is adhered to in order to provide the individual some comfort regarding his/her ultimate salvation or damnation. Likewise, even historical figures and founders closer to the present are not recognized or appreciated. Harold Bloom correctly notices that “the Assemblies of God…does not honor [William] Seymour, but without him they would not exist” (174). Likewise, “the Baptist tradition in America, for all its fiery intensity, has as little to do with Roger Williams as with the German Anabaptists of the sixteenth century…” (193). Thus, “what is spiritually alive in the mainline groupings is rarely a restored intensity of historical and doctrinal Protestantism” (46). Instead, it is something wholly new and experiential, which, like Gnosticism, disguises its existence under the guise of something old. Like the Gnostics, Evangelicals look back to the mythic past, believing they are recreating the religious environment of the early church. “The Baptists, true to the American grain…trace their origin in a great American myth, [to] the primitive Christian Church of ancient Israel” (46). The lack of historical consistency and the appeal to a mythic past is no doubt a product of the various sects’ emphasis on individual and personal revelation.

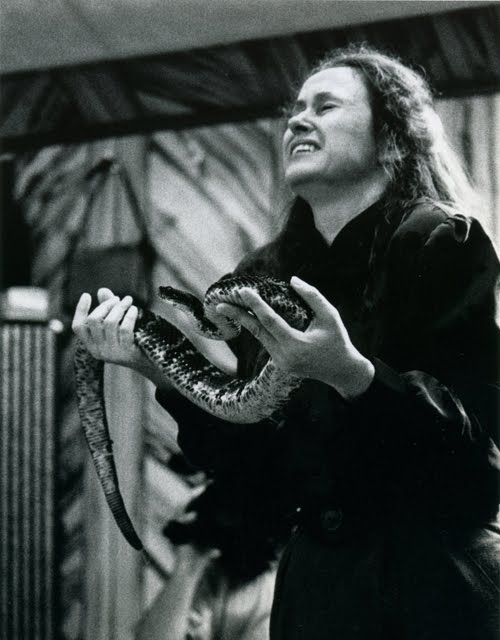

Sacraments New and Revised

The above-mentioned emphasis on religious experience and personal revelation brings about a change in the employment of sacraments. Those sacraments traditionally held as central, such as Baptism and the Eucharist, are reduced in importance and phenomenologically replaced with others. As Rudolph states, for the Gnostic “sacraments like baptism and the last supper (eucharist) cannot effect salvation and therefore do not possess those qualities that are ‘necessary for salvation’; at most they can confirm and strengthen that state of grace that the gnostics (pneumatics) enjoy already…” (218). Gnostics devised their own practices and sacraments, for example “the anointing…[which] could be made to serve as a special ‘redemption’ ceremony for the ‘perfect’, even displacing baptism” (229). Likewise, “‘redemption’ also [became]…a ritual act” and was made “a regular sacrament” (243). Specific sacraments were also performed for the dying, which involved anointing with oil (244). Most central, however, was the “ceremony of the ‘bridal chamber’…evidently…a form of the ritually shaped ‘redemption’ as the statements of the Gospel of Philip suggest to us…” (245). Rudolph posits that “the object in view was evidently to anticipate the final union with the Pleroma (represented as a bridal chamber) at the end of time and realizing it in the sacrament…” (245). Evangelicals, too, have re-imagined the role of sacraments in their services. Balmer points out that “the Lord’s Supper” is observed “once a month at most and sometimes as infrequently as once a year” (112). Additionally, the sacrament of the Eucharist is greatly reduced in importance, for the grape juice and saltine cracker, understood in a symbolic sense, are vehemently not the Body and Blood of Christ (Covington 115-6). To replace this void in worship, other practices become sacramental in a phenomenological sense. For instance, the Baptists engage in a ritualistic foot-washing ceremony, which holds as much weight as the Eucharist in many “high church” establishments. For the Pentecostal, speaking in tongues is a kind of “second blessing,” and upwellings of the Spirit, including dancing, speaking in tongues, shaking, convulsing, and being “slain in the Spirit,” are, on a phenomenological level, sacramental. Similarly, within the context of snake-handling churches, the acts of being “anointed,” taking up snakes, handling fire, and drinking strychnine without being harmed also operate as sacraments. Thus, the innovative tendency of Gnosticism and Evangelicalism, coupled with an emphasis on personal experience, gives rise to varied and new sacraments and ritual practices that express the group’s unique character.

Perfection and Morality

Although Rudolph claims that Gnosticism is “only half-heartedly interested, if at all, in ethical questions,” this is simply not the case. He states that “it has been established that the overwhelming majority of the sources give unequivocal support to…asceticism and abstinence,” but fails to see that these, in themselves, encompass strict moral guidelines about what behavior is proper, and what behavior is forbidden and will only entangle the practitioner in lust, desire, and materiality. Especially in the Thomas school “the practical consequences of the [central] myth are seen to be ascetic disengagement from the realm of darkness and from legalistic adherence to the religious laws of the authorities” (Layton 360). Although Gnostics rejected traditional morality, they formed very important ascetic values and practices of their own. Indeed, if these injunctions were properly followed “dominion over sin” would occur and one would realize the kingdom of God as already present. Thus, perfection was attainable in this embodied life! Similar sentiments are found in Evangelicalism. Although Evangelicals often denounce the Roman Catholic Church for requiring its priests to remain sexually abstinent, almost every other aspect of Gnostic morality is present in Evangelicalism. Indeed, even some Evangelical groups, such as the Shakers, required abstinence. Like Gnostic ascetics, Evangelicals are often teetotalist in nature, rejecting intoxicating drink, smoking, drugs, dancing, and sometimes things as seemingly benign as movies and secular music. This moral imperative is most obvious in the Holiness movement, “emanating from John Wesley’s conviction that the biblical injunction ‘Be ye perfect’ should be taken literally and that complete freedom from sin was possible in this life” (Balmer 227). Likewise, the famous revivalist Charles Finney “assured [whole masses of souls that they] could cleanse [themselves] forever of all human sin en route to the goal of ‘entire sanctification’” (Bloom 73). Clearly then, for both Evangelicals and Gnostics, proper behavior and morality derived from a powerful religious experience requires continued adherence that would eventually result in a kind of existential perfection or “heavenly state.”

Conclusion

While comparing Gnostic beliefs to modern religious sensibilities has become somewhat fashionable of late, a close consideration of both Evangelicalism and Gnosticism reveals interesting similarities, often not those so casually and incorrectly cited by the unobservant or uneducated. Clearly, both groups are minorities within larger religious communities, and thus adopt “in-group” rhetoric in order to identify themselves as separate from, and above, the ordinary mass of believers. This, in turn, gives rise to dualistic conceptions of anthropogony, society, and ontology. In this sense, both groups are probably influenced by Jewish apocalypticism, in which it was believed that the current, corrupt, and degenerate age would perish, and the faithful would enjoy the splendor of heaven while the damned burned in hellfire. Obviously, these dualisms breed a negative view of the world, where the traps of vice and sin reside, attempting to foil the religiously observant individual’s spiritual aspirations. The existence of such a fallen world, and the relative weakness of the faithful, creates a strong emphasis on the soteriological role of the savior. Similarly, both traditions draw heavily from the intellectual material of their time, and synthesize it with myths or beliefs they either creatively derive from scripture or claim to be self-evident. The most central aspect of both Gnosticism and Evangelicalism is their emphasis on personal, religious experience, in which one gains “acquaintance” with God and knows he/she is saved. This ideological imperative tends to displace the importance of creed and historical teachings, granting both religious movements freedom to create new and innovative doctrines and theologies. Being highly individualized, both religious structures tend to redefine the importance of “official” sacraments, and indeed create some of their own in order to better facilitate their new revelations. Both Evangelicalism and Gnosticism place high importance on how one behaves, what one does with one’s body, and how one acts in the world. For both, abstinence from certain behavior and substances is important, for certain activities result in sin, attachment, and the loss of one’s salvation. Finally, both believe that if one behaves properly, is open to the savior, and is graced with His acquaintance, perfection is possible to attain in this life and body, granting the individual a view of the glory to come after death.