How State Ambivalence Towards Religion Profited Chan in Song China and Soto Zen in Tokugawa Japan

Religion throughout history has often had an ambivalent relationship with the state. I will argue that the relationships between the state and the Buddhist monastic institution in both Song China and Tokugawa Japan reflect this ambivalence, with government policies that revealed a wariness of religion while simultaneously co-opting the religious establishment in order to further government interests. Furthermore, the Chan sect in Song China and the Soto Zen sect in Tokugawa Japan similarly profited from this state of state ambivalence, each rising to dominate their respective religious landscapes due to government policies.

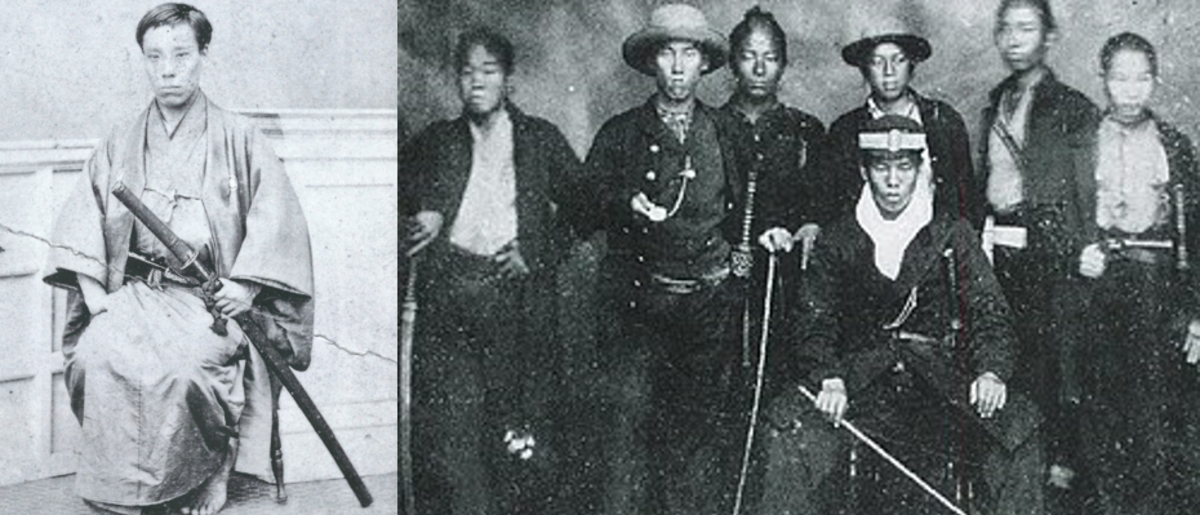

In Tokugawa Japan, state ambivalence towards religion was evident in the way it persecuted certain religious traditions, yet simultaneously worked closely with the monastic institution of Buddhism. The Tokugawa government saw the spread of Christianity, with its notions of loyalty to God over state1, as a subversive “threat to its hegemony”2 In 1614, Christianity was banned in Japan3, initiating a lengthy period of persecution which sometimes even involved the torture and killing of Christians and members of other “heretical” religious sects4 While the Tokugawa government thus acted out of fear to eradicate certain forms of religion, they utilized another form of religion (Buddhism) to establish a universal system of state control, whereby the government could closely monitor the entire populace through its mandatory temple registration system5.

As every person in Japan was required to be registered at a Buddhist temple, their was a tremendous influx of parishioners, who tended to gravitate to the temple closest to them, regardless of the temple's sect affiliation6. Soto Zen capitalized on this fact by establishing over seventeen thousand temples throughout Japan, building myriad small temples for placement in even the smallest villages7. In this way, governmental policy led to unprecedented institutional growth for Soto Buddhism8, such that Soto Zen became the largest sect of Buddhism in Japan9. This system solidified Soto Zen's hold over the religious landscape in an enduring way, as it was not individuals, but entire families and their future posterity who became tied to a particular parish temple10. Moreover, the governmental backing of the parish system gave parish temples the power needed to enforce a set of both ritual and financial obligations on all their parishioners, as anyone who refused to financially support the temple as the temple saw fit could be taken off the temple registry11. Such people were automatically included in a “Registry of Nonhumans”, and thus faced myriad forms of discrimination or even persecution12. So the enduring ties between households and the now enormous Soto Zen sect were no merely nominal connections, but provided the financial basis upon which Soto Zen could grow and prosper. So a symbiotic relationship developed between Soto Zen and the state, whereby the the state used the Zen to enforce its political agenda of control, and Zen profited from this by being enabled to expand its presence in Japan like never before13.

Similarly, state ambivalence toward religion in Song China led to the dominance of Chan over the rest of monastic Buddhism via the state's promotion of public monasteries (as opposed to hereditary monasteries)14, which the government could most effectively control15. This promotion of public monasteries propelled Chan to dominance due to a little understood special association of Chan with public monasteries—these may have “began as an institutionalization of the Chan school”16—, predating the government's measures to actively promote such monasteries.17 In China, however, the government's fear of religion was directed at Buddhism itself, rather than on a “foreign” religion18. I put “foreign” in quotes to highlight the fact that Buddhism itself, although quite entrenched in Chinese society by the time of the Song dynasty, was not native to China. Also, the Song government's courtship of religion seemed to center more on a desire to obtain for the emperor and the state the safety and prosperity conferred by Buddhist intercession19, rather than on a desire to use the monastic institution as a means for closely monitoring its populace.

While government measures to control religion in Tokugawa Japan seemed to focus on controlling οἱ πολλοί (hoi polloi) through the monastic institution, in Song China efforts at control—these included measures such as the occasional purging of unregistered monasteries20—were directed more at the monastic institution itself. Thus, there was no coercion of the populace to become Buddhist parishioners, and therefore no base from which the monastic establishment could exert nearly the degree of power over the laity as was seen in Tokugawa Japan.

While Schlutter does not explicitly state that the Chan school proactively “capitalized” on government policies, as Willliams says of Soto Zen in Tokugawa Japan21, further research to support such a conclusion may be justified. After all, dharma transmission “had a special association with Chan”22, and was of monumental importance, both for the fledgling careers of Chan students23, and for the ability of established Chan abbots to procreate their dharma lineage24. Since “only someone who held . . . a position as the abbot of a public monastery could perform valid dharma transmissions”25, there would seem to have been every reason for Chan clergy to have worked hand in hand with the government's agenda to promote public monasteries, rather than merely sit by as passive recipients of the benefits which such an agenda bestowed on the Chan sect.

In conclusion, the ruling regimes in both Tokugawa Japan and Song China showed a marked ambivalence towards religion. Although there were differences in how this ambivalence manifested, and in the specific government policies which resulted from this ambivalence, the resultant policies nonetheless propelled both Soto Zen and Chinese Chan to a position of dominance within their respective religious and cultural milieus.

1Williams, Duncan. The Other Side of Zen, p. 16

2Williams, p. 15

3Williams, p. 16

4Williams, p. 22

5Williams, p. 19 - 20

6Williams, p. 20

7Ibid.

8Williams, p. 7

9Williams, p. 1

10Williams, p. 23

11Williams, p. 24

12Williams, p. 25

13Williams, p. 122

14Schlutter, Morten. How Zen Became Zen, p. 41, 53

15Schlutter, p. 41

16Schlutter, p. 45

17Schlutter, p. 45 - 48

18Schlutter, p. 31

19Schlutter, p. 31 - 32

20Schlutter, p. 34

21Williams, p. 20

22Schlutter, p. 59

23Schlutter, p. 60 – 64, 68

24Schlutter, p. 68

25Schlutter, p. 67