Was Jesus a Postmodernist?

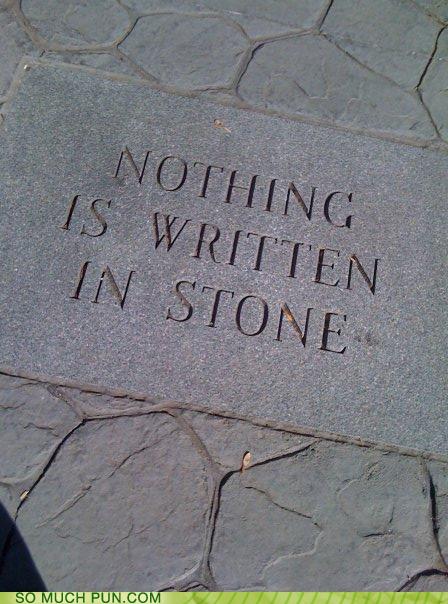

The word "postmodern" gets thrown around a lot. Whether in relation to art, literature, history or philosophy, there is a certain allure to the idea of something being postmodern. It is beyond modern, more enlightened than many millennia of thought, and the very word is imbued with a sense of intellectualism and sophistication. Aside from its allure however, postmodernism as a philosophy is rarely properly understood, and yet its effect on Western culture is undeniable. In the U.S. today, the idea of moral absolutes is often met with derision and accompanied by words such as “intolerance” and “bigotry,” while the mere mention of objective truth produces visible discomfort and an abrupt end to conversation (or the beginning of a heated one). Why is this so? At what point did Western society decide that individual opinion was the determiner of truth? Why did we allow the moral blurring of day-time talk shows to trump the timeless authority of Scripture? There is no one answer to these questions, but understanding the principles of postmodernism as well as the reasons behind its inception may help towards shifting today’s social milieu towards a less relativistic, less skeptical outlook.

To properly understand postmodernism, we need first to examine it in relation to its predecessor, modernism. Traditionally, the modernistic worldview is considered to have begun after the fall of the French Bastille in 1789 and to have been the dominant school of thought up until the latter half of the 20th century. With close attachments to the Enlightenment, modernism can be defined as the attempt to create an explanation for everything. As Millard Erickson puts it:

"Darwinism accounted for everything in terms of biological evolution. Freudian psychology explained all human behavior in light of sexual energy, repression and unconscious forces. Marxism interpreted all events of history in economic categories, with the forces of dialectical materialism moving history toward the inevitable classless society. These ideologies offered universal diagnoses as well as universal cures."[1]

The move towards an even more “modern” process of thought began with an overall disillusionment with modernism. The overarching goals that modernism hoped to achieve have ultimately been unfulfilled. The promise of moral and ethical enlightenment arising from rationality has proven to be but a mere repetition of mankind’s depravity and selfishness. Technological and intellectual progress, while improving the quality of life in numerous ways, have not only failed to solve a majority of the world’s complications, but have resulted in new and complex problems never before dreamed of.

[1] Millard Erickson, Christian Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2007), 164.

Rising from the ashes of this optimistic and modernistic worldview was “postmodernism.” Though parallels between these two worldviews exist, the points of departure are stark. While modernism hoped that through empirical rationalism an objective reality could be ascertained, postmodernism rejects any idea of absolute truth. “Faith and Reason,” a PBS documentary on the relationship between religion and science, defines postmodernism as such:

…[a] reaction to the assumed certainty of scientific, or objective, efforts to explain reality. In essence, it stems from a recognition that reality is not simply mirrored in human understanding of it, but rather, is constructed as the mind tries to understand its own particular and personal reality. For this reason, postmodernism is highly skeptical of explanations which claim to be valid for all groups, cultures, traditions, or races, and instead focuses on the relative truths of each person. In the postmodern understanding, interpretation is everything; reality only comes into being through our interpretations of what the world means to us individually. Postmodernism relies on concrete experience over abstract principles, knowing always that the outcome of one's own experience will necessarily be fallible and relative, rather than certain and universal. [1]

Given this definition, it is easy to detect the departure points between this philosophy and Christianity. While Christians can fully appreciate the postmodern distrust in modernist claims to discovering an explanation for everything, we should also recognize that the sentiment goes too far in its assertion that truth is simply relative. The literalistic approach to history espoused by the Bible plus the obvious claims to both truth and the perspicuity of scripture by Jesus Christ and the apostles absolutely preclude the concept of postmodern relativism. So although postmodernism refuses to assert that any one worldview holds more weight than any other, it seems that those worldviews holding to an objective stance on issues of morality are even more weightless than the others.

[1]OPB, “Faith and Reason.” http://www.pbs.org/faithandreason/ (accessed December 14, 2010).

The most grievous offense for the postmodern mind, it seems, is to label a belief or action as “wrong” or “immoral,” or a truth as objective and absolute. This then, is the area of greatest divergence from the postmodern concept of reality versus the biblically-based one. The traditional Christian understanding of the exclusivity of Christ for receiving salvation for instance, flies in the face of much postmodern thought. What appears to the Christian to be a historically grounded and accurately transmitted text is to many of the postmodern mindset a mere inspiration at best, a sexist, homophobic, and racist treatise on humanity at worst. Speaking of history, this raises complications as well.

The postmodern view of history, while no longer as prevalent as in the past, is every bit as cynical and non-committal as its view of truth. The traditional historical method (gathering all relevant evidence, making thoughtful deductions while aiming for the highest level of objectivity possible) is no longer tenable within postmodern thought. History has been recorded by the winners and, since it tells the story of their victory, cannot be trusted. Though this is a generalization of a complex issue, the fact remains that this attempt at redefining history into something more resembling literary fiction than objective reality is of great consequence for the story of the Gospel.

The notion of the fallibility of history is really nothing new. Historians have for years recognized the inherent problems existing within historiography, namely, the “fallibility and deficiency of the record upon which it is based; the fallibility and selectivity inherent in the writing of history; and the fallibility and subjectivity of the historian.”[1] The issues facing the traditional approach to history however, pale in comparison to the complications created from the postmodern approach. Scholar Gertrude Himmelfarb compares these two mindsets:

"What the traditional historian sees as an event that actually occurred in

the past, the postmodernist sees as only a ‘text’ that exists in the present –

a text to be parsed, glossed, construed, interpreted by the historian, much as

a novel or poem is by the critic. And, like any literary text, the historical

text is indeterminate and contradictory, paradoxical and ironic, so that it can

be “textualized,” “contextualized,” “recontextualized” and intertextualized” at

will – the “text” being little more that a “pretext” for the creative historian."

[2]

[1] Gertrude Himmelfarb, “Telling it as you Like it,” in The Postmodern History Reader, ed. Keith Jenkins (New York: Routledge, 1997), 159

[2] Ibid., 162

There are serious problems with this approach, the least of being the danger of rewriting or forgetting altogether events of great implication and importance (i.e. the Holocaust). But beyond this, can it really be said that no occurrences in history can be maintained to be “truthful?” Subjectivity aside, things did happen, and people did write them down. For instance, say that at this very moment I look up from my laptop and witness my cat stroll into the room where I am sitting. I then take note of the exact time and date, and write upon a piece of paper, “At exactly 4:43 pm on December 16, 2010, a brown cat walked into the room where I was sitting.” Say then that I took great care to ensure the preservation of this paper, locking it into a disaster-proof safe and burying it in my backyard, whereas 500 years later an archeologist happened upon this safe and was able to extract the paper and read it. Granted, subjectivity can be ascertained even from such a factual statement concerning a cat walking into a room. I may have failed to mention a dog also walking into the room, thus betraying a preference for cats. I may have had a different concept of brown (russet) than the historian (sepia), and the fact that I preserved this bit of information over any other speaks volumes regarding my priorities. But the point is this: no matter what questions the historian may ask, the fact remains that at a certain point during December 16, 2010, a cat did indeed walk into a room. This did occur, and no amount of suspicion, skepticism or reinterpretation on the part of the historian can change that fact.

To the Christian, a factual belief in historical events is crucially important. Had the New Testament’s record of the resurrection of Christ been a mere metaphor (or worse, a flat-out lie) our faith and our preaching is, as Paul himself so urgently stated, utterly futile. Reality in history and the ability of mankind to assess that reality accurately is at the very foundation of Christian belief, and the ability, reliability, and accuracy of the biblical authors is something we not only need to rely upon, but defend. Granted, relying upon the authority of scripture to argue the authority of scripture to the postmodernist may seem a fruitless endeavor. While the Bible may have said “…we did not follow cleverly devised tales when we made known to you the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ, but we were eyewitnesses of His majesty,”[1] to one who denies or questions the historical validity of the document such words are of little consequence.[2] But even so, by what means then does the Christian use to defend the Bible? Does one garner authority for the words of God by appealing to disciplines invented by mankind such as archeology, textual criticism or history? Richard Pratt offers good insight on the subject:

"If, however, trust in Christ is founded on logical consistency, historical evidence, scientific arguments, etc., then Christ is yet to be received as the ultimate authority. The various foundations are more authoritative than Christ himself. To use yet another analogy, if belief in Christian truth comes only after the claims of Christ are run through the verification machine of human judgment, then human judgment is still thought to be the ultimate authority." [3]

The Christian must stand firmly upon the authority of God as revealed through His word. By beginning at a point of neutrality, the very standard being used to validate the Bible then becomes a standard possessing a greater degree of authority. The Bible, as odd as may sound, can prove the Bible. But is this circular reasoning? Perhaps, but what discipline is immune to it? Or better, what standard can stand up under scrutiny when the one opposed to the authority of the Bible is unwilling to give one inch of ground? If one appeals to archaeology, another can point out those archaeologists who find the Bible to be unreliable. If one appeals to history, there is no limit to the historians who view the Bible as yet one more archaic book of myths from the ancient world, and so and on and so forth. As Michael Kruger states, “If Christians insist on a neutral starting point and fail to challenge their opponents intellectual loyalties, the results will hardly be a surprise: non-Christian presuppositions will lead to non-Christian interpretations and ultimately to non-Christian conclusions.”[4]

[1] 2 Peter 1:16 (NASB).

[2] This is, of course, not considering the potential for the supernatural in regards to scripture’s ability to change hearts and minds, but that is for another essay.

[3]Richard L. Pratt, Every Thought Captive (Phillipsburg, N.J.: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1979) 79-80.

[4] Michael J. Kruger, “The Sufficiency of Scripture in Apologetics.” TMSJ 12/1 (Spring 2001) 75.

The Christian presupposition then, is key. The Bible and the Christian worldview are truthful simply because all other views of reality fall under the weight of that very reality. The failure of the postmodern mindset to produce yet one viable explanation for life, reality, existence, etc. (or to even desire to do so) should be enough to at least open the door to a consideration that the Bible may in fact be the word of God. Of course, given the tenets he holds to, once the postmodernist takes an objective stance on any issue he is instantly acting in opposition to his own tenets. The indeterminate nature of reality coupled with the idea of our own ineptitude in approximating this reality leaves the postmodernist at a loss when trying to pin down any absolute, and this is the greatest challenge when defending the authority of scripture against the postmodern worldview. No amount of factual, scientific, or historical evidence can break through a mind fortified by the conviction that all biblical evidence is relative and open to wide interpretation.

Despite the strength of the Christian’s presupposition, the nature of Scripture is such that while it needs no outside support, all support given will only prove to increase its validity. The historical reliability of the Bible is such as to impress the most ardent critic, as it boasts a manuscript tradition that is second to none. No other ancient document comes close to the amount of manuscripts (over 5000 for the New Testament) nor do any other manuscript copies come so close in time to the actual events depicted. The uniqueness of the Bible narrative is such that critics have long been scratching their heads trying to come up with reasons for why such outlandish events have been written in such precise, detailed, and seemingly “historical” ways. These are no simple myths, nor have they been presented as such, which forces the skeptic to formulate naturalistic theories almost as improbable as the events themselves. For instance, in his article, “A Skeptics Guide to Passover,” Michael Lucas rehashes the old theories on the parting of the red sea (a natural phenomena known as a “wind setdown”), the ten plagues of Egypt (a domino effect due to the volcanic eruption of the island of Santorini) and the burning bush (self-combustion coupled with a drug-induced hallucination).[1] Of course Lucas, like all those before him, fails to mention the drowning of the Egyptian army, the strange selectiveness of the ten plagues, and the fact that hallucinations don’t repeatedly order one to do a specific task (a task that resulted in ten plagues and the parting of the Red Sea no doubt!). Prophecies within the Bible pose a problem for the skeptic as well. It has proven difficult for the critic to discount Daniel’s prediction of not only Alexander the Great’s accomplishments, but the division of his empire into four and the rise of Rome (they are simply forced to date it after the events depicted). Add to this the numerous detailed prophecies concerning Christ throughout the Old Testament, and the task of dispelling becomes yet more laborious. And speaking of Christ, the record of his life alone is one the most, if not the most compelling case for the miraculous ever presented.[1] Lucas, Michael. “A Skeptic’s Guide to Passover.” Slate, available from http://www.slate.com/id/2215127/ (accessed December 17, 2010).

Multiple accounts attest to the burial of Jesus, the discovery of an empty tomb, the reappearance of Jesus, and the fervor with which his early disciples spread the Gospel. Skeptic’s explanations for these events invariably fall short, as nothing matches the evidence better than the written account. Despite all attempts at rewriting history, the Gospel’s record has remained has such: A corpse was placed into a tomb and sealed with a massive stone moved into place by several Roman soldiers. In hopes of thwarting a possible theft, a group of soldiers was assigned to guard the tomb, and yet, the tomb was found empty by female followers of Jesus the third day after he was executed. Jesus then appeared to not only his disciples, but a group of hundreds of people before his ascension, sparking the greatest religious movement in the history of mankind.

The most compelling of all these descriptions, I believe, is the fervency of Christ’s disciples in spreading the message of the Gospel. It is simply unthinkable that the apostles, after viewing the death of their leader-the one who had promised to bring about a new kingdom-would have done anything but simply dissolved and reintegrated themselves into society. The fact that the majority of these men were unflinchingly willing to face execution rather than deny the message of Christ speaks volumes to the truthfulness of this account. It alone can speak for the authority of the Bible, and yet it is but one of a multitude of proofs of the revelatory nature of the Scriptures.

The postmodern mind lies at a quandary. The self-refuting, contradictory nature of relativism is all too evident to the believer, and yet remains veiled to the skeptic:

“He verbally and outwardly rejects the Christian God and claims that He does not exist, but then turns around and lives as though there really were such a God. He says the universe is just all chance and matter in motion, and yet he kisses his wife good-bye as though there were really something abstract called “love” in the world. He proclaims a universe where tooth and claw reign, but then takes moral offense at murders and rapes announced on the evening news.”[1]

Postmodernism, like all “isms” before it, will eventually run its course. But after this worldview fully fades into the ether, a new and improved way of regarding the world will appear, and like its predecessors, will wax and wane with the whims of society. And right alongside it all, like the proverbial woman of wisdom crying out, will be the truth of God’s revelation, offering one of the greatest gifts a human can receive: The comfort in knowing that absolute truth exists, that we can grasp hold of it, and that it is good.

[1] Michael J. Kruger, “The Sufficiency of Scripture in Apologetics.” TMSJ 12/1 (Spring 2001)