The Condemnation of Magic

From the earliest biblical texts, magic and sorcery were believed to have been prevalent in society through the times of the Roman Empire, the Middle Ages, and the early modern period of European history. As the practice of magic became increasingly attached to heresy and, eventually, “maleficium”, leaders of the Church grew quite alarmed by what was taking place in Europe by the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries – so alarmed, in fact, that the condemnation of sorcery and witchcraft became a widespread phenomenon of paranoia, judicial corruption, and unjust persecutions. The Church felt particularly threatened by the practice of magic at this time because it went against the teachings of the Bible, it could tempt people to worship the Devil or lose faith in God, and nearly all forms of magic, by this point, were considered evil.

Early Justifiable Magic

In the first centuries of the Common Era, the practice of magic existed in the world through priests and magicians, and although sorcery in Roman law was punishable by death, magic could at least be justified for these types of individuals. There was an instance in the second century CE when a Latin writer and philosopher named Lucius Apuleius was accused of sorcery by his wife’s relatives because they were suspicious of his marriage to her; Apuleius was able to successfully defend himself from these accusations the way any magician might defend the practice of their craft. During his defense speech, he asks, “…What is a sorcerer? I have read in many books that magus is the same thing in Persian as priest in our language. What crime is there in being a priest and in having accurate knowledge, a science, a technique of traditional ritual, sacred rites and traditional law…” (Luck, 110-113). One could conclude that magic was not considered a great threat to the Church at this point in time; otherwise, Apuleius would not have attempted to justify the practice of magic by bringing up priests. He even uses religion itself as a strong defense when boldly stating, “[Magic] is an art acceptable to the immortal gods, an art which includes the knowledge of how to worship them and pay homage. It is a religious tradition…” (110-113). By using priests and religion itself as a defense, Apuleius makes it clear to us that the practicing of magic could still be viewed in a positive way by society, the law, and the Church in certain circumstances; it had not yet begun to evolve into the essence of fear.

The Witch Evolution Begins

A huge contributing factor to the Church’s fear of sorcery was how society viewed witches as being so evil and powerful during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. In the earliest centuries, witches were commonly viewed as mediums that could communicate with the deceased and did not tend to be portrayed as the vile, unholy creatures they came to be treated as. In an utmost ironic way, Lucius Apuleius wrote a work of fiction called The Golden Ass; this work consisted of two narratives, both illustrating the power of witches. The irony stems from Apuleius’s skepticism toward the more maleficent powers of witches, and so while his work may not have been intended to be interpreted seriously, his stories contributed greatly to the way witches were portrayed in later centuries. One of the narratives in The Golden Ass introduces the possibility of witches being able to take the form of other creatures through metamorphosis and gnaw their victim’s faces. Apuleius writes, “’While that learned young student was keeping careful watch over my corpse, the ghoulish witches who were hovering near, waiting for a chance to rob it, did their best to deceive him by changing shape…””…they had slipped in through a knot-hole disguised as weasels and mice. But they threw a fog of sleep over him, so that he fell insensible…’” (Apuleius, 42-50). These malicious and metamorphic powers opened up a new realm of possibilities when it came to witchcraft and laid an unintended foundation for the image of the classic witch.

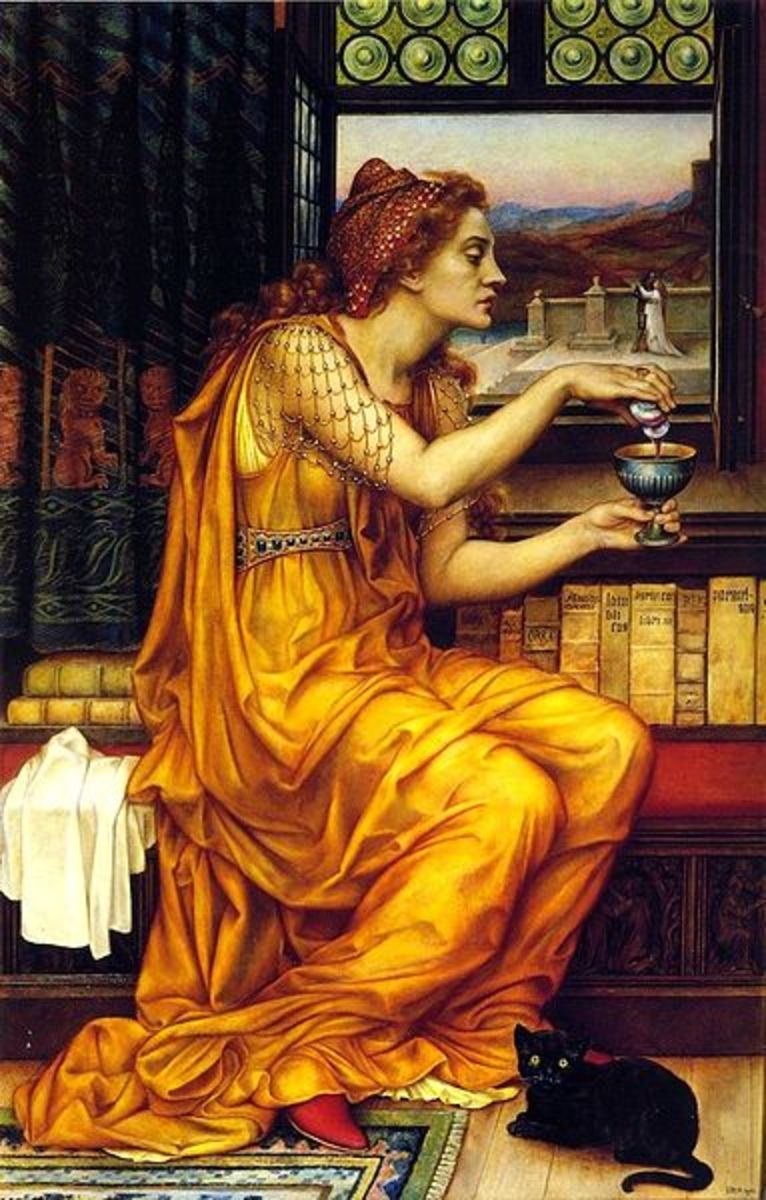

The Canidia Influence

In an even more ironic and tragic case of fiction being taken too seriously by the mass majority of readers, Quintus Horatius Flaccus, a Latin poet, wrote a satirical piece about a witch named Canidia in his Fifth Epode. Canidia is the leader of a group of witches whom she utilizes to kidnap a Roman boy, take his liver, and use it to create a love potion. Canidia is portrayed as the most sinister and powerful witch depicted up to that time, as Horace describes that “her locks and disheveled head entwined with short vipers, orders wild fig-trees uprooted from the tombs, funereal cypresses, eggs and feathers of a night-roving screech-owl smeared with the blood of a hideous toad, herbs that Iolcos and Iberia, fertile in poisons, send, and bones snatched from the jaws of a starving bitch – all those to be burned into magic flames” (Horace, 375-381). Horace’s description of Canidia is a dramatic one, and that was done for a clear purpose; the writing was meant to be an exaggeration of how witches were already being depicted Before Common Era, and was meant to make a mockery of witchcraft. Unfortunately, this piece of writing did the opposite of that and greatly contributed to the way witches were later viewed.

The Sorcery Trial of Alice Kyteler

Witches and sorcery started to become a real threat to leaders of the Church in correlation with the increase of witch trials and the severity of the crimes committed. It seemed that by the 1300s, superstition and imagination were beginning to evolve people’s perceptions of witches (as well as the literary influences previously mentioned); this evolution reached a milestone in the case of Dame Alice Kyteler, who was tried for sorcery in Ireland, 1324. Alice was accused, along with her associates, of sacrificing animals to a demon and using enchanted items to persuade young men to give her their possessions, as well as committing murder. What made Alice’s trial unique for that time was her relationship with an incubus demon, her rejection of God, and the way she carried out evil deeds through influence. In The Sorcery Trial of Alice Kyteler, L.S. Davidson and J.O. Ward write, “Seventh, that the said lady had a certain demon as incubus by whom she permitted herself to be known carnally…” and, “After being six times whipped on the order of the bishop for her sorceries, and finally found out to be a heretic, [an accomplice of Alice] admitted in front of all the clergy and people that under the influence of the said Dame Alice, she had totally rejected faith in Christ and the church, and three times on Alice’s behalf she had sacrificed to demons” (26-30, 62-63, 70). The Church had every reason to be alarmed by sorcery at this point, because witchcraft was evolving into something that both went against the teachings of the Church and was capable of influencing others to reject faith in God. Things the Church claimed that God would never permit were now being done by demons and the Devil as illustrated in the confessions of these crimes; with so much power and so many possibilities, one could hypothesize that the Church feared that these trials would convince people that God is not almighty, and that many would lose faith and possibly turn to the Devil.

The Condemnation

Cases of magic and mysterious evil began to set off a paranoia effect in Europe; with unknown diseases being created and spread, a lack of understanding of science and the human mind, and a human tendency to create delusions in a desperate attempt to make sense of one’s life, magic was to blame for almost anything. Magic was something not understood by the majority of people, and because of the influence of writings and the confessions of those accused of sorcery, people let their imaginations run wild. There were so many unexplained, bad things that would happen in these people’s lives and magic was an easy means of blame – so easy, in fact, that it was condemned by the University of Paris in 1398. Magic was associated with maleficium - harmful and sinister acts - to the point where the theology faculty approved twenty-eight articles condemning the practice of ritual magic. There is significant evidence in their arguments that show how threatened the Church was by magic and how it was now considered blasphemous in nearly every way. The pronouncement included, “…that it is allowed to use magical arts or other kinds of superstition prohibited by God and the Church for any good moral purpose. This is an error because according to the Apostle, evil cannot be done that good may result from it”, which basically clarifies that all magic is evil, no matter what purpose it is used for, and “…that by such arts the holy prophets and other saints had the power of their prophecies and performed miracles or expelled demons. This is an error and blasphemy” (Paris, 1580). The university basically said, “Forget all that magic you learned about in the Bible; that is completely different from how it is being used today and it is not okay for anyone to attempt any magic anymore”. This condemnation of magic was a spark that set off the widespread condemning and prosecuting of sorcerers (primarily witches) during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

The Church’s actions against the practice of magic are testaments to the power of influence. Stories, rumors, and the wild imagination people had in such a mysterious time of human history were responsible for the creation of magic, and just as they were responsible for its creation, they were the leading factors of its condemnation. The Church and its teaches acted as the majority of people’s understandings of life, death, morality, and what it means to be human, just as it does today; but when those sacred teachings are challenged by an evolving society and by limitless human imagination, the institution that dictates these teachings is bound to face that challenge. Unfortunately, the Church had to face its greatest challenge during a time when so many factors of life were not yet understood, therefore, rationality was absent in the minds of many. Paranoia got the best of the Church, the kingdoms, its citizens, and all of Europe in these dark chapters of human history and it was possibly the harshest mistake we would ever learn from as human beings.

Sources

Luck, Georg. Arcana Mundi: Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Collection of Ancient Texts (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985), 110-113.

Apuleius. The Golden Ass, trans. R. Graves (New York, 1951), 42-50.

Horace. Epode V, Canidia’s Incantation, trans. C.E. Bennett.

Horace. Horace, the Odes and Epodes (Cambridge, MA, 1914), 375-381.

L.S. Davidson, J.O. Ward, eds., The Sorcery Trial of Alice Kyteler (Binghamton: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 1993), 26-70.

Démonomanie des sorciers (Paris, 1580).