Rabbits: The Real Watership Down

Emerging From The Burrow

The Book That Inspired A Hub

Life In The Warren

The popular misconception about rabbits is that they devote all of their time to feeding and procreation. In reality, rabbit life is far more varied and complex than that. Take their social structure, for instance. Each population is sub-divided into distinct breeding groups comprising up to four males and up to eight females, who defend a territory around their warren. By day, the activities of each group are largely restricted to the area within the clearly marked and defended territory boundaries. But after dusk, feeding is concentrated over a larger home range.

Within each group is a strict hierarchy among the adult members of each sex. The females (does) tend to be closely related- mothers, daughters and aunts- while the males (bucks) who defend them are unrelated. This is because young females remain with their mothers and sisters but their brothers disperse. The females tend to live longer lives than the males, with even great-great grandmothers still reproducing. Rabbit social groups have demonstrated both remarkable loyalty to a particular warren and consistency of membership, allowing the dominant males to potentially remain in control for many years.

When the number of adult females in a breeding group increases to more than six, group ‘budding’ occurs. One or two does (not necessarily the youngest) start restricting their activities to peripheral burrows within the defended territory. It becomes increasingly difficult for the dominant males to maintain control over females in two warrens, and so an immigrant buck will challenge for ownership of the tearaway does. A new social group thus emerges within the colony.

On the whole, Watership Down- style migrations of entire social groups are extremely rare. This phenomenon typically occurs after heavy fox predation, when the widowed does left behind are highly vulnerable to attack. But there have been recorded cases of regular seasonal migration between summer and winter homes more than 300 feet apart by adult females, alone or accompanied by their daughters.

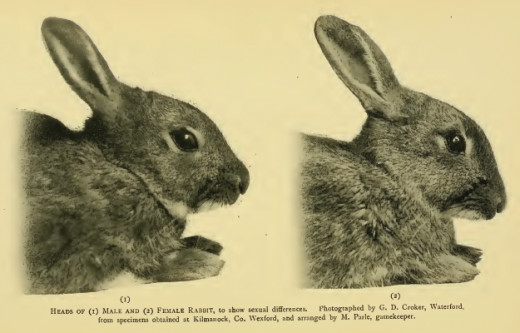

Male And Female

Rabbit Combat

Tough At The Top

It’s exceptionally tough at the top for the males. They have to guard their does against outsiders, keep subordinate bucks in their place and intervene when the females chase one another or attack each other’s young. The overwhelming benefit of dominance is successful gene propagation- i.e. fathering more offspring- but the disadvantages include a far higher risk of predation. Policing one’s harem and defending it from rivals means there is less time to look out for approaching foxes and other such predators.

On emerging after an underground siesta, the top males have to patrol their territory boundaries, scent-making them with urine and secretions from their chin and anal glands to ensure that their neighbours respect these borders. Alpha males usually adopt a gloves-on approach to encounters with rivals. First, they pawscrape and scent mark furiously at each other, then, tails held aloft, they ‘parallel-run’ along the boundary- you can see something similar among rival deer during the autumn rut. Occasionally, if an aspiring young buck persistently tries to usurp the dominant male, the gloves come off and a jump fight ensues. The combatants leap at or past each other, often inflicting serious damage with kicks from their hind legs.

Dominant males can be identified by their significantly larger testes and higher levels of scent marking behaviour alone. If a dominant buck is lost, the testes of a fortunate subordinate will dramatically increase in size within just a few days- and he will take over.

Another Literary Classic Featuring Rabbits

A Wild Baby Rabbit

Fighting Females

It’s not just the males who fight. Dominant females can be very aggressive towards their subordinates and the young born to other does, occasionally killing new-born kittens while they’re still in the nest. There’s no meerkat style babysitting here. Even tiny babies bicker, biting each other’s’ bottoms and spin-chasing in a circle until one lets go.

While the males are competing for does, the females are vying for safe nesting sites within the main warren. Heavily pregnant subordinates ready to give birth, their mouths full of nesting material, are repeatedly chased away from the burrow by higher ranking females. This is probably because predators are attracted to warrens where there is a glut of young emerging, since baby rabbits are easy prey. Despite the close relationships between females, the selfish gene soon kicks into action.

Breeding- and the rapidity with which they can do it- is one of the things that rabbits are famous for. Even the most hardened cynic would be impressed by how well these mammals are adapted to reproduce. Induced ovulation, post-partum oestrous, a gestation period of just 30 days, naked, blind nestlings developing into independent young after just three weeks- all these characteristics have evolved to promote opportunistic breeding when climatic conditions provide enough food resources, or when previous nestlings fall victim to predators. A mother doe is often lactating and pregnant at the same time, chasing her current litter away when she is about to give birth to the next batch.

But despite this legendary potential, the mortality rate amongst youngsters is extremely high. During years of high fox and weasel predation, it’s common for only one or two young to actually emerge from the nesting burrow.

The breeding season is generally brief- March or April to June, with first litters occasionally appearing in February if the winter is mild. The young are born into a fur lined nest and the doe only visits once a day, suckling her offspring in a veritable feeding frenzy. Nursing lasts just 5-10 minutes, with the highly nutritious milk jet propelled into the babies’ mouths. Subordinate females that have been denied access to warrens, and dominant does at times of high fox predation may give birth in purpose excavated breeding stops. Invisible to human eyes, the entrances to these simple, temporary burrows are meticulously opened then refilled with soil after each daily visit.

Spending so little time with nestlings is unusual in mammals (female rats, for instance, spend 90 per cent of their day with their new-borns), but absentee parentism does have its benefits- by seemingly neglecting their babies, the mothers are effectively keeping their whereabouts concealed from potential predators.

The European Rabbit's Ancestral Home

Myxomatosis: The Facts

- Myxoma viruses originate from the Americas, where certain species of cottontail rabbit are the natural host.

- The disease is spread by arthropods, with fleas and mosquitoes being the most common vectors in Europe.

- The first signs of myxomatosis are slight swellings of the eyelids and nose followed by more extensive lesions at the base of the ears. Survival varies according to weather, predation pressures, age and genetic resistance.

- Myxomatosis first appeared in Kent in the early 1950s and, despite Government attempts to contain the outbreak, was deliberately spread by farmers wanting to reduce rabbit populations on their farms.

- The disease is believed to have killed more than 99 per cent of the UK's rabbits in the following years, with dramatic effects on rabbit-dependent ecosystems and species.

Afflicted Bunny

Lost In Spain

To understand why the European rabbit evolved this strategy, we have to look at the predation pressures in its ancestral home on the Iberian Peninsula. Even today, the rabbit is a key prey item for more than 45 predators, including the Iberian lynx and imperial eagle.

However, rabbit populations have declined so dramatically in Spain and Portugal over the past 20 years that the species is now threatened with extinction in these countries. The factors responsible for this decline have been a combination of introduced viruses (myxoma and rabbit haemorrhagic disease), overhunting and habitat loss and fragmentation. As a consequence, the entire rabbit dependent ecosystem could collapse.

Even in the UK, the image of the rabbit is transforming from farmers’ enemy to conservation ally. The rabbit’s grazing and burrowing activities have been recognised as key management tools in a range of threatened habitats that are high in biodiversity. These include the botanically rich chalk grasslands essential for rare butterflies to breed, and the heathland environment sought after by stone curlews. The rabbit creates the micro-habitat conditions previously provided by declining agricultural practices or the native animal populations now lost from these ecosystems.

Similarly rabbits have been vital to the recovery of several rare species of raptor and mammal here in the UK, such as the polecat. One of the primary aims of our research is to use what we’ve learnt to reintroduce the rabbit to key ancestral areas where it is close to extinction.

It’s time to forget the image of the rabbit as a procreating chomper of all things green. We need to appreciate its important role in threatened European ecosystems and its fascinating behaviour and biology.

© 2013 James Kenny