The Passenger Pigeon

World War I began in 1914, so in 2014 we began marking the centennial of a lot of sad events in Europe. September 1, 2014 marked an equally sad moment in North America. The last known passenger pigeon, once the most numerous bird on the continent and possibly the world, died in the Cincinnati Zoo. Today one can only wonder how could this animal, which once numbered in the billions, be gone forever?

Early Hunters

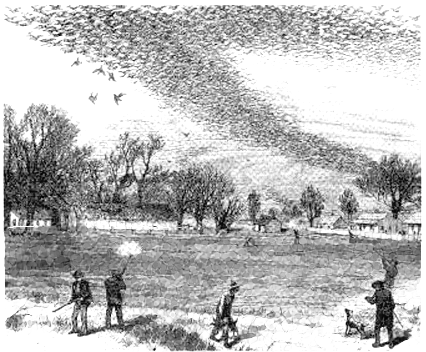

Fossil specimens of passenger pigeons have been found in North America which date back 100,000 years. No one knows how numerous they were in Pre-European times. They were a food source for Indians and settlers alike during the colonization of America. Passenger pigeons flocks numbered in the millions of birds, and tree branches in their nesting areas would often break due to their weight. They inhabited most of North America east of the Rocky Mountains.

Native Americans harvested young birds from nesting areas with long poles at night. These were considered the tastiest, and they did not wish to drive away the adults. They also used nets to capture adults away from nesting grounds. The only game bird more important to Indians was the turkey. Naturally, American settlers used guns to hunt them, just like they did for other game. They were a vital food source on the frontier. They were so numerous one did not have to be a good shot to shoot enough for dinner. Trapping and other methods were also used to capture or kill passenger pigeons.

Commercial Exploitation

The passenger pigeon's habit of nesting in huge flocks always attracted predators, even before humans arrived in the New World. Their flocks were so large, local predators like mink, wolves, foxes or hawks hardly dented the colonies. Even Indians and frontier settlers didn't have much effect. What started their decline was when railroads made it profitable to kill and ship the pigeons to the large eastern cities. Some of the numbers are staggering. After the railroad came to Plattsburg, New York, 1.8 million birds were shipped out in 1851 at a price of about four cents apiece.

By 1876, shipping costs and low prices made it unprofitable to kill birds and ship them east. The only practical method of refrigeration at this time was ice, which was harvested in the winter and stored. Companies began to employ trappers who captured the birds alive. This eliminated the need for ice to keep the meat from spoiling. In addition to the railroad, the telegraph was another major factor in the passenger pigeon's decline. It spread the word of a large flock far and wide which allowed hunters and trappers to quickly converge on it.

Conservation - Too Little, Too Late

Many thought the passenger pigeons would always be numerous, but there were a few who saw the problem to come. In 1857, a bill was introduced in the Ohio legislature to protect the species. The committee that studied the issue reported "The passenger pigeon needs no protection." It wasn't until forty years later that Michigan became the first state to fully protect them. The last known one in the wild was shot in Laurel, Indiana in 1902.

The Cincinnati Zoo opened in 1875 and is the second oldest in the nation, after the Philadelphia Zoo. Charles Whitman from the University of Chicago had some success breeding passenger pigeons, and sent some birds to the Cincinnati Zoo. Despite four live hatchings in 1880, they were ultimately unsuccessful to sustain a breeding flock in captivity. The last male died in 1910, and $1,000 was offered for another male, which was never claimed The last survivor was Martha, who died on September 1, 1914. In 1866, less than fifty years earlier, a flock one mile wide and 300 miles long was reported in southern Ontario. It was estimated to contain 3.5 billion passenger pigeons.

The Cincinnati Zoo was very forward thinking, and pioneered captive breeding to prevent extinction of bird species. Despite their best efforts, they couldn't save the passenger pigeon. In a cruel irony, the last Carolina parakeet perished in the same aviary where Martha died less than four years later. Their attempts no doubt laid the groundwork for later successful captive breeding programs. By 1987, the California condor population had dropped to only 22, all of which had been captured for captive breeding. This program, led by the San Diego Zoo, has been successful. By 2016, there were over 400 birds alive, with nearly 300 living wild.

Martha's Legacy

After she passed away, Martha was packed in ice and shipped to the Smithsonian Museum, where she was analyzed and preserved. Periodically she appears in exhibits there, most recently in the 2014-2015 exhibit "Once there were billions." In 1974 she returned to the Cincinnati Zoo for the Passenger Pigeon Memorial dedication ceremony. One of their original 1875 buildings, a pagoda style structure that served as an aviary, now tells the story of the passenger pigeon. There is also a statue of Martha at the zoo.