World of Snakes: The Regius, or Ball, Python

Called Royal because Cleopatra fancied them?

Sadly, Captivity may be their Only Hope

Many readers in HP and outside have read my articles on snakes and other reptiles, as well as those on spiders and scorpions.

You will have seen I usually advise people not to own dangerous pets, both for their sake and that of the creature, especially one caught and removed from its natural habitat.

Why? Well, imagine if you were taken from you home and all the freedom and its pleasures you had enjoyed for some years denied you from then on as you were placed in some prison. You would adapt badly and would never be really happy again. But if you had been born in a harsh confined environment with many of your peers, and later moved to another enclosure where you were treated much better and even with love and affection, you might think the gods had smiled on you and you had won the lottery of life.

It is more or less the same for wild creatures, even those with the slow metabolism and lack of emotion as the reptiles.

The Python Regius, also known as the Ball or Royal Python does not adapt well or easily when caught in the wild and such creatures should NOT be acquired. This is mainly due to the diet as the snakes really miss their diets they had in the wild and do not take easily to freezer mice, or other similar domestic diet.

Because of its size, the Ball Python, has become one of the most popular snakes in the pet trade. It rarely grows much over 3 to 4 feet and rarely bites after reaching maturity in captivity. Its name comes from the fact the, after hissing at you, it rolls into a tight ball in defence, with the head and tail tucked inside.

The python is a native to many countries and states of Africa. In one, Nigeria, it is revered by the Igbo Tribe and treated with care if it intrudes into an Igbo village where it is carefully retuned to the wild.

It is indeed a beautifully marked constrictor, ranging from black to dark brown with light brown to gold sides and blotches. The belly is cream, sometimes with black touches. It is the smallest python in length, but is stocky and very powerful when mature. It is normally docile, both in the wild and in captivity, but it has a very nasty bite you won't want to experience twice. This means handle infrequently and with care. You may want to wear gloves when handling young snakes as, like teenagers, they can be wild and have a nip with impunity. Use great care when feeding, as the snake may grab for his prey and get your thumb by mistake. (Is that damn snake grinning!).

The snake's stocky body is emphasized by its slim neck and oval head, with four distinct heat -receptor pits. Its scales are smoother than many other snakes, interrupted by two spurs by the anus.

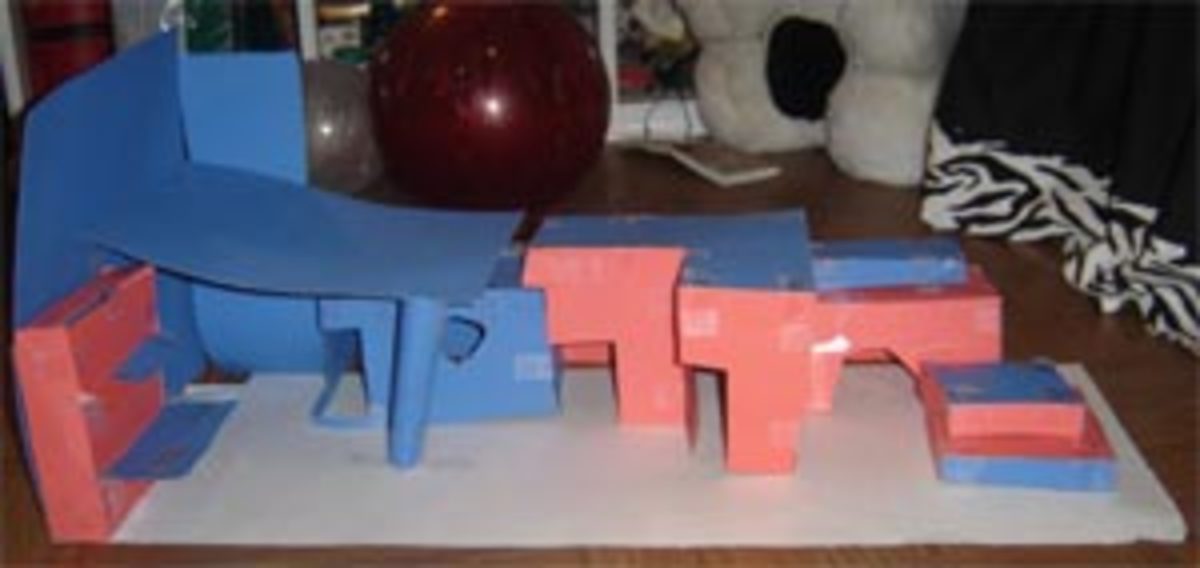

Landscape its aquarium home to imitate light wooded country with a couple of places it can hide in and an area for it to "sun itself" After feeding, it will want to rest for some days, even weeks and it doesn't enjoy being tied into a reef-knot by little Alfie while it's digesting its dinner.

Your python can live for 40 years or even more, so it is a good pet with which to grow old together. (Those owners over 40 might include the snake in their wills!).

Like all snakes, the Ball Python is cold-blooded and needs some ingenuity in the wild to control its temperature with the extremes between stifling heat and numbing cold of its tropical environment. It achieves this by living in old burrows, rock crevices, or hollow trees, etc., where it can move around as the temperature changes.

A reptile's forked tongue is one of the wonders of nature as it picks up "smells" - particles - in the air and "reads" them by pits in the roof of the mouth. This involves the very sensitive "Jacobsen's Organ," small chambers lined with membranes, and feed into the snake's brain, telling him what is around him, along with his eyes and their vertical pupils.

As they grow, the snake’s skin will be shed; a Ball Python may shed several times a year and less when fully mature. (make sure all the old skin comes away).

Snakes probably evolved from burrowing lizards way back in time, although we still lack the full fossil record on the intermediary species which would confirm this.

This snake doesn’t climb much in the wild and usually lives in a habitat which includes a handy water supply, such as a river, in which it sometimes bathes in very hot weather. You might consider this when building its artificial home; if large enough - and the tank should never be too small - you must include a water-feature which your snake will love. Along with this desire to create a similar environment to the woods in Africa, including a stout tree limb angled so the python can climb is de rigueur.

There’s lots of information online about available vivariums, or cages and this is not for this introductory hub.

Remember, like Steve McQueen, snakes are wonderful escape artists and will take great pleasure in strangling kitty, so make sure any enclosure is escape proof and the kids can’t get in, either, (A large Ball Python can easily constrict and choke a small child).

A Ball is a tropical creature and should be kept at about 75F to 85F degrees during the day and allowed to cool to F68 to F72 at night. As you will not want to suffer such daytime heat, a separate cage heater is required, (If you want easy, buy a mini-Schnauzer!).

Ball Pythons, along with many other reptiles and wild animals are becoming unobtainable from the wild. In part, this is due to increased vigilance by wild-life inspectors and customs personnel, but, ironically, perhaps the biggest reason is that their habitat is so decreased by man’s expansion and farming needs, there are far fewer creatures left to catch. Those that remain are in inaccessible areas or in wild-life parks where their capture is prevented or regulated.

This actually puts pressure on breeders, fanciers and zoos, etc., to realize the future on the planet of the threatened creatures in which they deal is in jeopardy; on their efforts alone might depend the preservation of these beautiful and shy creatures.

This why I have written this article, because the last thing I wanted to do in the past was to encourage the ownership of creatures like these. I used to say “Leave them alone in the wild to enjoy their lives away from man’s interference.” But soon, their - and hundreds of other creature’s - only chance may be in benign captivity. I find that heartbreaking, but a fact of life reporters have to deal with.