- HubPages»

- Arts and Design»

- Crafts & Handiwork»

- Textiles

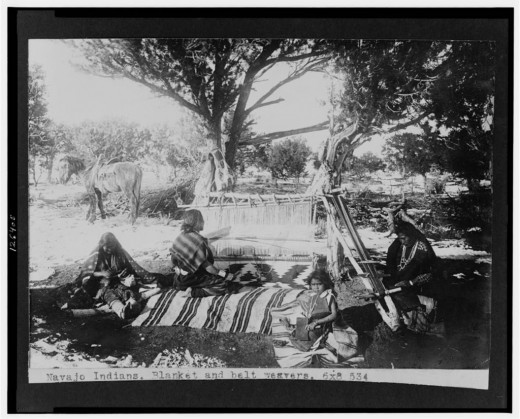

About Art Textiles and the Navajo Weavers Who Make Them in the Twenty First Century

Navajo Weavers and Art Dealers

- Learn more about the history of Navajo textiles at the Crownpoint Navajo Rug Auction. This auction site operates out of the town of Crownpoint, in New Mexico, and is run by the Native American weavers without a middleman. The auction takes place at the elementary school monthly.

- Nelson Tsosie - A Navajo artist who works in a wide range of mediums, but really excels in his stylized bronzes.

- Santa Fe Indian Market is an art show and sale in Santa Fe that showcases the work of hundred of native American artists each year. Click the link to go to the offiicial site and view more information about this sale.

- The Navajo Nation Fair runs for a week in Window Rock Arizona and hosts a fine arts exhibition that showcases all kinds of Navajo handcrafts and fine art, including jewelry, weaving, and other types of items.

This Story Isn't a Yarn

I met her at the Arizona home of a wealthy Navajo "rug" dealer. He had invited us to his house in a remote part of southern Arizona that is an escape for an elite and wealthy subset of the population. My husband is a museum professional, and at the small institution where he was working, he was both the exhibit designer and preparator, as well as the collections manager. We had travelled there with our small family while they planned the details of the exhibit showcasing some exquisitely crafted weaving by Navajo artists in the private collection of the dealer. This particular exhibition was to showcase Navajo weavings that this collector had personally commissioned.

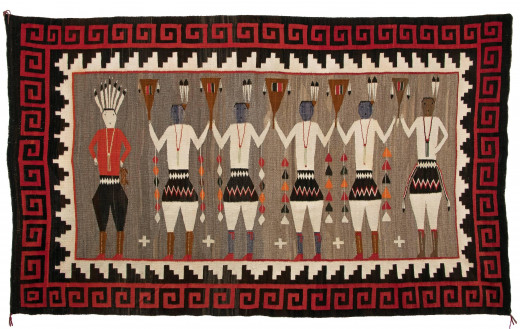

The dealer and his wife invited us to stay in their guest house overnight, because the nearest hotel was over 30 miles away in nearby Tucson. The main home was a sprawling, older ranch house. On the outside, despite its large size, it was not ostentatious, and in fact, despite a lovely patio garden, looked like a large southern Arizona farmhouse. Inside their home, the hallmark of tastefully appointed high-style southwest was everywhere. And weavings, known colloquially as Navajo rugs, were hanging on just about every wall of the house. And these weren't just any Navajo rugs. These were of the highest possible quality, using hand-dyed wools and outrageously high per-inch thread count. Our collector and dealer was showcasing his fine collection of weavings he had commissioned for the exhibit. Several of the weavings in his collection were large, ornate, and oversized, with intricate patterns. He mentioned to my husband and me that he worked closely with the artists and even suggested designs that he wanted to see in the rugs.

Navajo art is an important folk art that tells one part of the story of the American West and of the Navajo people and culture. Some of these weavings, pre-dating 1930, according to one Navajo art web site, can sell at auction for over $100,000 a piece.

When our hosts invited us inside their home, they introduced us to Mary (not her real name), who was staying with them. She was about my age (30-something), maybe a little bit younger, and they didn't exactly explain who she was. Our hosts told us that Mary normally stayed at the guest house (a two-bedroom affair with comfortable amenities and privacy), but we would stay there overnight and she would just stay with them at the big house.

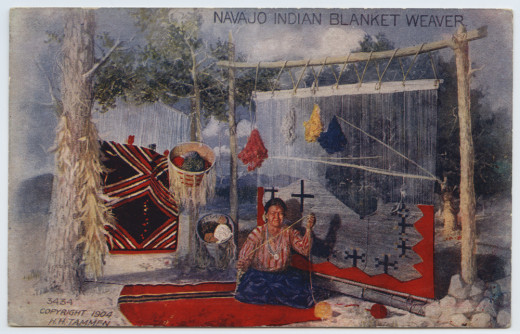

Mary is a Navajo weaver. She was living with our hosts, and in exchange for an hourly wage, which she intimated was similar to what she would make working at a grocery store, would spend literally months completing these astounding works of art, in the Navajo tradition. Our hosts provided the materials to her, purchasing the finest wool from dealers, and she would prepare it and then weave it into intricate, and I might add, perfect, geometric designs. Then, when her artwork was complete, if I understand the system correctly, she would hand it over to the art dealer, who added it to his collection and sold it to high end clients that he kept on a roladex in his kitchen. This hire-an-artist system wasn't quite patronage, since the patronage system doesn't usually involve flipping art like a banked-owned home. Patronage also usually offers the artist some flexibility in their creative process. Mary comes from one of the most sought-after weaving families in the world of Navajo textile art, and her multi-generational family all had representative works at the art exhibit my husband was painstakingly planning with his persnickety and difficult to please art collector.

Because I didn't have a role in planning the exhibition, and Mary's workspace was in the guest house, I sat and talked with her for a while one day. First, I asked her about her loom. Was it heavy? How was she able to move such a large loom to create wall-sized tapestries from her home to this remote place? Wasn't the loom heavy and difficult to move around?

She laughed at my assumptions. Not at all, she said. My brother made me a special loom from PVC pipe, so it's actually quite simple to move the loom pieces around, and they weigh very little. She invited me to come in and watch her work. She showed me the way the vertical threads on the loom created a frame work for the weaving, and I was surprised to see that she didn't complete her pattern one line at a time, but actually worked with different thread colors to create a free-hand design which she then back filled with other colors.

I was mesmerized. I have always had a keen sense that my husband's work has put me in some unique and unusual situations. And this was one of those times. I asked her some more questions about how she spent her time. She said she worked long days. Sometimes for hours and hours a day, beginning at 6:00 a.m. and ending in the evening.

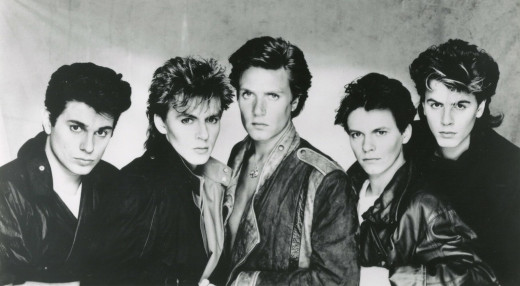

I asked her if she ever got bored, and she admitted that the work could be tedious. She said she listened to music to help pass the time. My experience of the Navajo mystique was fueled by an a.m. radio station we would hear as we drove the long and lonely stretch of highway that connects Gallup New Mexico to Southern Colorado. This stretch of highway is route 666 and it goes right through the Navajo reservation. During my many road trips I'd turn on the radio and listen to chants by Navajo elders in a transfixing language I didn't understand. I always looked forward to being nearly hypnotized by this music when I drove through this stretch of our travels, but my husband would just roll his eyes at me and take the opportunity to have a long nap if it was my turn to drive. Fueled by these memories, I asked Mary if she listened to Navajo music to help inspire her work, and she fixed me with a steady and patient stare that I couldn't quite read. Then she told me she really liked Duran Duran and that mostly she listened to old 80s technopop.

She worked quickly and accurately weaving hand-dyed wool threads through the weft and warp of the loom. Finally, when the art dealer and his wife were no longer in ear shot, I asked Mary, in the most awkward way possible, if she felt taken advantage of by these people. The look she gave me said I had crossed a line. I felt sheepish! First, she told me that the question I asked her would never even be considered by a Navajo. They just don't think that way. And second, they were really nice people that were giving her an opportunity to practice a dying art. "What would I be doing if I weren't here?" she asked, then answered her own question: "I'd be making the same amount of money or even less working at a grocery store or a convenience store."

Still, I wasn't quite convinced. I have been to some amazing Native American owned and operated art galleries in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and I know that anyone who ever travelled a remote highway in Arizona or New Mexico to discover an Indian hawking his or her wares by the side of the road was doing so in a bygone era. Native American art, since it has come to be appreciated for its signficant cultural and aesthetic quality, has shot through the roof in value.

I had to ask her the obvious question. Why don't you buy the materials yourself and sell them directly to buyers instead of doing the work for an art dealer who is making (I guessed) about 80% profit from your work?

From my perspective, paying someone an hourly wage to practice artwork is tantamount to extortion.

Her response was dour. The wools and the dyes are very very expensive. I can't afford the kinds of quality materials he brings to us. Besides, these rugs take hours and hours to make. If I did this on my own, I'd probably have to give it up so I could take on a 'real' job to support my family.

And, so, quickly I was made to face my own cultural biases and blindnesses to the challenges Navajo and other native artists face. I had met Mary and become interested in her uniqueness and her differences. She comes from a fascinating culture and I wanted to understand that. But the result of our conversation was that I saw her as a modern person too, not just as a living relic of the old west.

I came away from our conversation questioning the ethics of a system that seems to favor art dealers over artists, though I was also left with many questions. I also realized that she was a Navajo first, a weaver second, and an artist last. Her work is beautiful.

More Navajo Art Links

- The Navajo Weaving Tradition

This in-depth article provides some additional insight into the history, influences, deeper cultural meaning, and artistry of the Navajo Weaving Tradition

© 2009 Carolyn Augustine