We Owe Thanks for Our World's Recorded History to one Tiny Insect, the Iron Gall Wasp.

The world of the gall wasp

Click thumbnail to view full-size

How a Wasp helped tell Man's History

When we hear the word "Gall," it has negative connotations to us: a bitter secretion in our "Gall Bladders" that all too commonly results in the disease of "Gall-stones," resulting in us having to have the offending organ removed; or we say some experience is "Galling," it leaves us feeling bitter and resentful.

What few of us might not also realize is that the title is also applied to a family of tiny insects - wasps - which can inject their eggs into the flower buds of trees - principally, the Oaks, resulting in the bulbous deformation we call "Oak Galls," the construction of which depends on the species of wasp using the tree for its young to survive. * see footnote

"OK, what's the big deal," you might comment as you read this. "I've never noticed the bloomin' phenomena anyway." High up in the leafy branches of our glorious and disappearing oak trees, the little swellings are difficult to see by ground level observers.

It's only when you are told if it were not for this tree disease, and the substance mankind has extracted from certain types of oak galls, we might not have any surviving historical chronicles penned from the approaching end of Roman times in Britain - about 400 AD - until well into the beginning of the 20th Century.

For most of the important documents were written in "IRON GALL INK," made from the "Gallotannic" acid extracted and pulverized from the galls, mixed with sulphate leached from scrap iron and fixed or "bound" with a binder like "Gum Arabic" etc. Other inks in use, such as the India Ink, have nowhere near the long life achieved with that from galls.

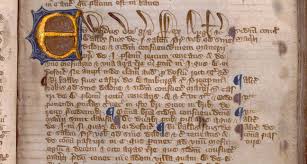

Iron gall ink, that dark brown, to purple, copper-plate compositions on parchment we are so familiar with from museums; our great libraries or even BBC documentaries. They were all fashioned using gall ink on the various qualities of parchment leaving a record hardly dimmed over the Millennia and available to our scholars and teachers perhaps for Millennia to come.

All because evolution programmed a tiny wasp to seek the protection of mighty oaks - the trees that also underpinned the construction of great war galleons and soaring cathedrals, as well as furniture by our emblematic artisans, among so much more.

Natural history museums often contain a collection of the galls themselves, interesting in their own right. Like the diversity of form found among sea shells - and, indeed, their formation similar to the defense of an oyster covering a irritant with layers of mother of pearl; the end result a lustrous pearl - the galls are actually the defense of the oak tree reacting to the alien in its branches and producing the wondrous little nurseries, fortress-like, in their protection of the growing young wasp.

And when you realize that there are actually close to 1500 species of the gall wasps world wide, you think, "Hey, this ain't no little thing!" North America has located 800 species; Europe, about 350; the rest spread around the planet, busy creating nurseries in many varieties of trees, but really loving the staunch oaks!

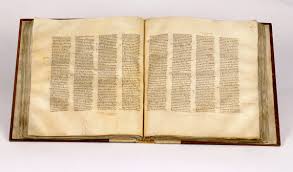

The actions of this tiny creature resulted in compositions like the Magna Carta, the "Codex "Sinaiticus," (world's oldest bible penned in the 4th. century AD), the US Constitution and literally millions of important legal, (The Magna Carta), scientific (Darwin's Letters), literary (Shakespeare's plays and sonnets), et al, in fact any record mankind was attempting to make permanent for his society and posterity for the hundreds of generations to come.

In fact, artists still use this fabulous product of nature and so would the world's chroniclers still if it were not for one milestone game-changing invention: resulting of one and all using modern paper, replacing parchment over the last couple of hundred years. Iron gall ink that marries so well to parchment doesn't do well with paper, destroying the fiber from which it is made. It actually resembled paint when used with parchment, but when applied to paper, burrows into the material causing damage and loss.

Gall ink was so stubborn when used on parchment, it could not be rubbed-out; we have many instances in the composers of our weighty parchment tomes showing scrapings and overwriting, when writers rectified mistakes with the knife blade rather than a rubber. You cannot feasibly do that with much thinner paper today. Of course, we have the benefit of being able to compose and edit electronically, allowing our luminaries like Hub Pages' contributors to produce, ahem, perfect compositions, and perhaps signalling the imminent end of paper itself!

Parchment is, of course, made from processed animal skins (leather), commonly from goat, sheep, and the finest (called Vellum) from the fetus of calves. It wears incredibly well, but must be kept in very dry conditions. As it is difficult for museums and libraries, etc., to actually distinguish which animal their parchment books and documents were made from, they use the general term "animal membrane;" and we can assume the most important records are written on vellum from the unlucky calves.

Artists and specialty writers can still obtain iron gall ink and, indeed, parchment, today, yet there is no large industry as once there was making the ink.

*footnote Wasps.

The huge family of the Hymenoptera, or wasps, including today's protagonists, the Cynipoidea, the Gall Wasps, are some of man's best friends on the planet. In particular, many species predate on creatures that are pests to man by laying their eggs in or on them resulting in the pest host's death. And now we find we owe much of our recorded history to this humble little 'buzzer with the painful venom. (Although the gall wasp species don't actually have the ability to sting you)

This writer actually loves wasps and doesn't swipe at them! They have never stung me and merely seem curious over me and my world. After a tour of my premises, they calmly leave out of the window again...with just perhaps a touch of marmalade on their toes from my breakfast!