Georgia O'Keeffe: The Secrets of Her Success Part 4

III. The Secrets of Her Success

There were many things that contributed to the success of Georgia O’Keeffe. Several of these were related to her unique personality and character strengths, for example her persistence, courage, and lack of the fear of scandal. One of the few external keys to her initial success was Alfred Stieglitz. However, later in her career he also affected her adversely.

From a very young age Georgia O’Keeffe knew what she wanted to do with her life. When she was in the eight grade she claimed, “I am going to be an artist” (“Young”) and from that time on she persistently pursued her goal. She practiced art her entire life. She lived to be ninety-eight years old and continued to practice and try new things as long as her health permitted her to do so (Lynch 47). She worked in oil painting up until the mid 1970’s when her failing eyesight made it too difficult to continue. However, she continued to draw in pencil and paint in watercolors until 1982. After her eye sight began to fail she learned how to work with clay and continued to do so until her health failed in 1984 (“About”). In an article written by M.T. Southgate, she compared O’Keeffe to the flowers that she painted. She wrote, “like the amaryllis, Georgia O’Keeffe only gave the impression of being fragile. Like the amaryllis, she could weather the negative criticism and changing styles by remaining close to the beliefs that nourished her” (Southgate 1900). She had the strength and persistence to weather the storm.

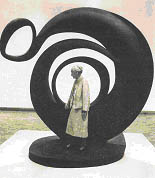

Even with her accumulating health issues, Georgia O’Keeffe demonstrated her persistence by continuing to practice art late into her life. In fact, it was during this time that she created some of her largest and most pretentious pieces. For example, in 1965 she painted “Sky Above the Clouds, IV” which was twenty-four feet long and eight feet tall (Gherman 108). She was inspired by the views from the airplane windows during a three and a half month long trip around the world that she took in 1959 (Hoffman 48). Another example, in 1982, when she was ninety-four years old, she was credited for the creation of “Abstraction,” a sculpture made from eleven feet of painted black aluminum. It was created for the San Francisco international sculpture show. It was based upon a smaller sculpture that she had created many years before. Interestingly, “it’s ‘head’ is turned as if to listen to the comments of the public -- something its creator never did” (Gherman 113).

Georgia O’Keeffe was an extremely courageous woman. In October of 1915 she wrote to Anita that “it always seems to me that so few people live -- they just seem to exist -- and I don’t see any reason why we shouldn’t live always . . . why do we do it all in our teens and twenties” (Pollitzer 31). To outsiders she seemed fearless, for example, on February 4, 1923, Henry McBride, the critic for the New York Sun, wrote that “. . . [t]he outstanding fact is that she is unafraid . . .” (184). However, she stated in an interview “I’m frightened all the time. But I’ve never let it stop me” (Krull 69). It isn’t courageous if you are unafraid. In another letter the same month to Anita she discussed her inconsistent fear of showing her work to other people. She stated that “. . . I am afraid that they won’t understand -- and I hope that they wont -- and am afraid they will” (Pollitzer 28). This demonstrates the internal battle that waged between her need for privacy and her need for expression (Bry 104). It was by overcoming her fears and courageously showing her work to the public that Georgia O’Keeffe became a successful artist. By 1922, “she had reconciled herself to exhibitions because she believed they were necessary to her success as an artist” (Lynes 96).

Alfred Stieglitz can be credited with much of the success during the early years of O’Keeffe’s artistic career. He was a photographer (“O’Keeffe and Stieglitz”). He opened ‘291 Fifth Avenue’ in 1905 and used “determination and discrimination . . . to support the artists in whom he believed” (Pollitzer 113). He was known as the “central figure in introducing modern artists in the United States” (Krull 69). In the first few years that he owned the gallery he displayed the works of Rodin, Matisse, John Marin, Toulouse-Lautrec, Henri Rousseau, Picasso, and Cézanne among others (Pollitzer 113). It was due to his support and promotion of their work that they achieved success within the United States.

On January 1, 1916, Anita Pollitzer had shown several of O’Keefe’s experimental charcoal drawings to Alfred Stieglitz (“About”). After receiving a letter from Anita informing her of her actions, O’Keeffe spontaneously decided to write Stieglitz herself. She wrote the following, “if you remember for a week why you liked my charcoals . . . and what they said to you -- I would like to know . . .” (Pollitzer 123). He replied, “. . . it is impossible to put into words what I saw and felt in your drawings . . . they were a genuine expression of yourself” (124). In May, Stieglitz exhibited ten of the charcoal drawings without O’Keeffe’s permission. He also made the mistake of labeling the work as created by “Virginia O’Keeffe” (Rathborne 81). She was angry and confronted him. During their argument he stated, “you have no more right to withhold those pictures . . . than to withdraw a child from the world” (Crunden 274). In the end, he won the argument and the drawings remained on display.

In the fall of 1916, Georgia O’Keeffe returned to Texas. She continued to teach as well as experiment with her art. She was now using watercolor as well as charcoal and paper. She also continued to write Anita and now Alfred Stieglitz as well. The following spring she sent several of her new works to Stieglitz and he organized her first solo show (Luke 71). The following month her first drawing sold for $400, which was considered a respectable amount for a new artist (Gherman 77). It was a drawing of a train departing from its station (Hoffman 6).

During the spring of 1918, Stieglitz offered to support O’Keeffe so that she could give up teaching, move to New York City, and create art full time for an entire year (Bry 99). Although he recognized her talent, it is unlikely that he ever considered that her “work could surpass his own or that of other men” (Lynes 16). From 1918 until his death in 1946, he managed her career, promoted her work, and organized annual exhibitions of her art (“About”). He also arranged the sales of her paintings and drawings. However, “he insisted that the pictures were for sale only to those who were worthy of them” (Pollitzer 117). He was already beginning to demonstrate an adverse effect on her career.

Another key to Georgia O’Keeffe’s success was her lack of the fear of scandal. When she first met Stieglitz, he was still married. Yet, they openly lived together from 1918 on, even though his divorce wasn’t final until 1924 (“O’Keeffe and Stieglitz”). O’Keeffe “. . . in her unconventional way, had no qualms about living with another woman’s husband” (Hoffman 25). In fact, after he was legally single again Stieglitz had to convince O’Keeffe to marry him. Since they had already survived the scandal of living together, she didn’t see why it was necessary to get married. He finally succeeded in convincing her and they were married late that year (“Young”). However, Georgia omitted the words “love, honor and obey” from her vows (Lisle 117).

During the early years of their relationship, Stieglitz was “obsessed with photographing Georgia” (“O’Keeffe and Stieglitz”). He took over three hundred photographs of her that “created a scandal in some circles” but, rather than feel ashamed “she took pleasure in them” (Krull 69). She saw them as “documents of Stieglitz’s love for her . . .” (Lynes 44). In fact, she even made jokes about the experience, for example, that “in three minutes you could have more itchy spots on you than you can imagine” (Gherman 78). She even laughed when other men commented to Stieglitz that they would enjoy similar photographs of their girlfriends and wives because of the intimate relationship involved. She stated “if they had known . . . I don’t think they would’ve been interested” (Lynes 55). He was particularly interested in O’Keeffe’s hands and it was said that these photographs “suggested both his intimacy with her touch, and the sensuality at the source of her painting” (Rathborne 54).

In 1921, he held an exhibition titled “A Woman.” It consisted of forty-five photographs, some clothed and some nude. Interestingly, all of the nude photographs were headless (Rathborne 15). During the exhibition he asked $5000 for a nude photograph (Lynes 43), which caused an even bigger scandal. Stieglitz continued to work on the series for many years and later revised the title to “Portrait of a Woman.” Many of the nude photographs were extreme close ups of specific parts of the body. For example, in 1923 he created the “Thigh and Buttocks” series which was described as “ a little known segment of the Portrait photographs” that were an “ambitious mix of naughtiness and abstractions” (Rathborne 17). Of the Portrait series, the critic, McBride wrote “. . . Mona Lisa got one portrait of herself worth talking about. O’Keeffe got a hundred” (Lynes 43).

During the late 1920’s there was a lot of conflict in the marriage. Stieglitz was possessive and controlling (Hoffman 39). It was observed by many that it was strange that someone as independent as O’Keeffe would tolerate marriage to someone as controlling as Stieglitz (Rathborne 16). O’Keeffe wanted to have children, but Stieglitz thought that he was too old and that they “would divert her from her painting” (Lisle 114). O’Keefe also wanted to build a house at Lake George where she could work but Stieglitz wouldn’t let her. She “now felt deprived of both solitude and independence. It was the first time in her life that she found herself repeatedly giving in against her will” (Pollitzer 198).

Stieglitz was often wrong about O’Keeffe and her work. For example, he was initially against both her flower and New York paintings. In 1924, O’Keeffe completed her first flower painting. When Stieglitz saw it he stated, “I don’t know how you’re going to get away with anything like that -- you aren’t planning to show it, are you?” (Lisle 137). This series of paintings later became both her best selling and her “signature work” (Callaway 107). However, she was so sensitive about the topic that she once told critic Emily Genauer, “I hate flowers -- I paint them because they’re cheaper than models and they don’t move!” (Lisle 144). The following year, O’Keeffe began painting the skyscrapers in New York City. Again, Stieglitz was not supportive. He stated that “even the men hadn’t done too well with it” (Chave 97). At her first showing of this series, the first painting sold for $1200. O’Keeffe commented that “from then on they let me paint New York” (Lisle 150).

As a result of Stieglitz’s attitude and the critics continued criticism Georgia O’Keeffe became physically ill. Dr. Dudley Roberts told her that it was also due to the stressful summers spent at Lake George with Stieglitz’s family, where she was responsible for everything (Pollitzer 198). She “realized . . . that neither she nor her work could continue to remain solely within the boundaries of the world she shared with Stieglitz” (Lynes 1). In the summer of 1929 she chose to instead visit New Mexico. She stated, “the Amarillo books were the hardest fight of my life… but going West was the hardest decision I ever had to make” (Pollitzer 199). From 1929 on Georgia began spending her summers alone in New Mexico and her winters in New York with Stieglitz (Bry 100). She purchased two houses, Ghost Ranch and Abiquiu (“About”). She no longer allowed Stieglitz to “influence her art” (Rathborne 85).

Although their relationship was often troubled, O’Keefe and Stieglitz remained close. On June 5, 1946 she left to spend the summer in New Mexico. They always wrote to each other while they were apart. “He would start to write her before she left for Abiquiu-- letters timed for her arrival there” (Pollitzer 249). On July 7, he wrote that he had a mild heart attack, “but it was alright and there was nothing to worry about” (250). On July 9, he had another heart attack (or some sources claim it was a stroke) and went into a coma (251). He died on July 13, 1946 (“Faraway”). In the obituaries, he was referred to as “ the husband of Georgia O’Keeffe . . . thus, at her mentor’s death, O’Keeffe… was as well known as her famous husband” (Lisle 267). It took O’Keefe three years to sort and distribute his estate (Pollitzer 252). During this time, she painted “Black Bird With Snow Covered Red Hills.” The painting depicts a “. . . bird winging straight ahead and alone over a huge expanse of whiteness . . . [it was] a picture of great beauty, with poignant meaning” (256). In 1949, O’Keefe moved to New Mexico permanently (“About”).

O’Keeffe was confronted with scandal later in life when the critics began to speculate about her relationship with a young potter named Juan Hamilton. In the fall of 1972 Hamilton came to her door looking for work (Hoffman 51). They became friends and she later hired him and he became her companion and business partner until her death (“Faraway”). Rather than become upset, the gossip about she and Juan merely “amused” her (Krull 71). After all, by the time they met she was in her eighties and he was only in his late twenties. He remained her companion and close friend until her death on March 6, 1986 at the age of ninety-eight (Krull 69). As she had requested, he had her cremated and then released her ashes on Mount Pedernal in her “faraway.” She had given her desert backyard the nickname several years before. It meant a “place of stark beauty and infinite space” (“Faraway”).