Georgia O'Keeffe: The Secrets of Her Success Part 5

IV. Georgia vs. The Critics

On the day that Alfred Stieglitz first exhibited the art of Georgia O’Keeffe an informal battle began between she and the critics. From 1916 on the two main topics of discussion among them were: 1) that she was a woman artist and the biases associated with this role, and 2) the meaning and interpretations of her paintings (Hoffman 57). They “found extraordinary interpretations . . . that were, she felt, far removed from her actual feeling” (Pollitzer 184). At the same time, Stieglitz “welcomed interpretation . . . he was glad of the talk about sex and the Freudian interpretations . . . [because it] made the curious come to view her work” (Pollitzer 184). Also in 1916 it was Stieglitz who began describing her work in Freudian terms as a promotional method (Lynes 2). He “loved controversy, sensation, and all that went with them. As far as he was concerned . . . the ends justified the means” (Lynes 60). In fact, he would go out of his way to create a stir. Before each show he would reprint the previous year’s reviews in order to start people talking (Rathborne 85). He would then invite the critics to the gallery before the exhibit opened, and then walk around and talk with them. One critic by the name of Edmund Wilson later discussed “how difficult it had been to separate his own ideas from Stieglitz’s” (Lynes 21). Stieglitz was known for the occasional publicity stunt. For example, in 1923 he sold six of the paintings in O’Keeffe’s “Calla Lilies” series for a total of $25,000 (Lynes 141). He then intentionally misled the critics to make them believe that a single painting had sold for that price. It the rumors had been true, at the time, it would have been the “highest sum ever paid to a living American artist” (Krull 71).

Prior to the twentieth century, men and women had lived in different spheres (Gadt 175). The men were the ones that were permitted to go out into the world and pursue careers while the women were expected to stay home and keep house. During the early twentieth century these trends were slowly changing. Women were now able to pursue educations, however, in the art field the women were expected to use their knowledge to teach, but not to earn their living from their art alone (Gherman 17). As a result of these prevailing trends, O’Keeffe was often confronted with the biases against women artists. For example, while she was at the Chicago Art Institute she met Eugene Speicher, a fellow student. He once told her that “she would never be much of a painter anyway . . . that she would, at best, only teach art in some girls school while he would become a painter” (Pollitzer 93). She was quoted as saying, “I would hear men saying, ‘she is pretty good for a woman,’ [or] ‘she paints like a man.’ That upset me” (Sawelson-Gorse 189). As a result, O’Keefe rebelled against being labeled a “woman artist” and would correct the people that called her this (Education).

The critic’s favorite target was Georgia O’Keeffe’s flower paintings, which she began in 1924. O’Keeffe claimed that “most people in the city rush around so they have no time to look and see a flower . . .” (Callaway 104) and that “she wanted people to be ‘surprised’ into taking the time to look . . . to see what I see of flowers” (Education). She even went so far as to say that “I want them to see it whether they want to or not” (Schwenger 62). The critics however saw “erotic interpretations in the large flower paintings . . .” (Bry 104), as well as themes of “decay and rebirth in nature” (“Georgia”). These descriptions were offensive to Georgia (Bry 104). However, the critics continued to describe them as anything from “unabashedly sensual” to “overtly erotic” to “spiritually chaste” (Callaway 105). Thomas Larson later wrote that perhaps the truth was a compromise between what the critics thought and what Georgia had to say. He stated that perhaps “she is naive about the interpretations of her work” (Larson 11). After all, many of her paintings that are the most criticized for being sexual in nature were created during the early and passionate years of her relationship with Stieglitz. It is possible that she demonstrated her sexual feelings unconsciously through her paintings (Hoffman 69).

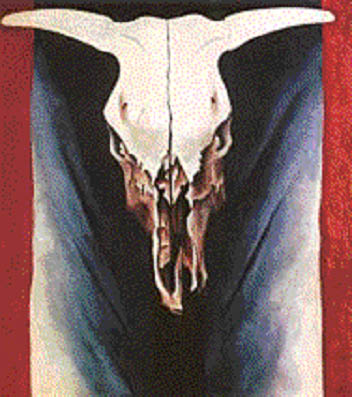

The critics’ second favorite target was Georgia O’Keefe’s skull and bone paintings. They claimed they “represent Life and/or Death . . . or Death and Resurrection” (Bry 102). Once again, “O’Keeffe steadfastly denied all religious and metaphysical interpretations of these paintings and insisted that she only painted what she saw” (102). In a conversation with Anita in 1931, O’Keeffe stated, “I painted my cow’s head because . . . in a way it was a symbol of the best part of America . . . cattle were important . . . I thought to myself, ‘Just for fun I will make it red, white and blue . . .” (Pollitzer 212). As Elizabeth Turner pointed out, O’Keeffe painted the bones in the same landscape in which they died “ . . . the cows and sheep whose introduction to the land reshaped it” (Turner 63)

(Coming soon: Georgia O'Keeffe: The Secrets of Her Success-- Part 6: A Role Model)

A complete list of research sources will be included in the final chapter of this series.