Kryptos

The most celebrated inscription at the Central Intelligence Agency’s headquarters in Langley, Virginia used to be “And ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free.” This biblical phrase is chiseled into marble and is displayed in the main lobby. Since 1990 another text has garnered most of the attention of CIA workers and visitors, 865 characters of apparent gibberish that are punched out of half-inch-thick copper and are part of a sculpture called Kryptos.

Sculpture Commission

During the 1980s the CIA planned an expansion known as the New Headquarters Building. They wanted some type of artwork that would sit between the two buildings, the new and the old, so a solicitation was sent out asking artists to submit proposals for a piece of art for the courtyard. This would be a piece of public art that the general public would never get to see. The winning artist would be provided with a $250,000 commission and the piece should somehow engender the feelings of well-being and hope.

The competition was won in 1988 by Jim Sanborn, a Georgetown artist. He named his sculpture Kryptos, which is the Greek word for hidden. The work is a meditation on the nature of secrecy and the elusiveness of truth, its message written entirely in code. Sanborn was introduced to Edward Scheidt, a retiring cryptographer, who gave him a crash course in the art of concealing text and helped devise the codes used in the sculpture. Sanborn and Scheidt spent four months devising the codes that would ultimately be used

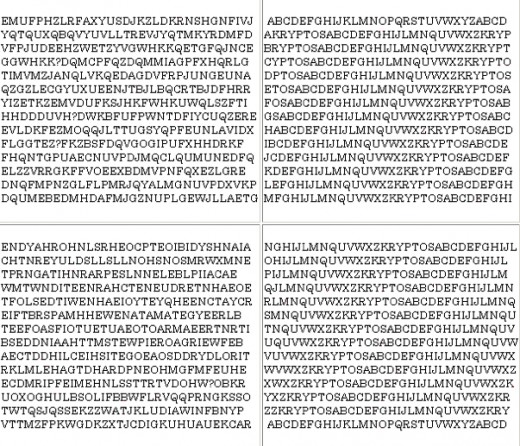

Kryptos is a 12-foot high, copper, granite and wood sculpture inscribed with four encrypted messages. The sculpture’s theme is intelligence gathering. It features a large block of petrified wood standing upright, with a tall copper plate scrolling out of the wood like a piece of paper. At the base is a round pool with a pump that sends water in a circular motion around the pool. There are approximately 1,800 letters carved out of the copper plate. Some of those letters form a table based on an encryption method developed in the 16th century; the rest form the encryption itself.

Letter to All CIA Employees from Jim Sanborn

When his work was about two-thirds complete, Sanborn sent a letter to all of the employees at Langley. The purpose of the letter was to let everyone know exactly what he was doing and to explain how the various segments of the sculpture related to each other and to the Central Intelligence Agency.

He explained that the large slabs of stone he was using would create a natural framework for the project as well as serve as a connection to the past when the site had natural stone outcroppings before the Agency. The stones would also serve to hold copper sheets through which letters and symbols would be cut to form ciphers. He explained that the first cipher would be International Morse Code and as you moved through the piece toward the courtyard the cipher would increase in its complexity.

He further explained there would be a petrified tree that would support a curved, copper plate through which approximately 2000 letters of the alphabet would be cut. The left side of the plate would be for deciphering code and the right side would be text to be deciphered by using the table and partly by using a challenging encoding system.

He then explained how his choice of materials was symbolic; the use of lodestone which refers to ancient navigational compasses, the petrified tree as the source of paper on which written language has been recorded, and the copper which represents perforated text. Water is used in two pools, one of which is tranquil and the other which is pumped in such a fashion as to circulate in a constant state of agitation around the base. Other grasses, trees and rocks are used to make the space more visually appealing and thought provoking.

He finished the letter by inviting anyone with interest to stop by and ask him anything they cared to about the project.

The Encryptions

Sanborn assumed the puzzles would be cracked within a short period of time. His expert, Scheidt, with a little more of an idea of what it would take to crack the code, figured it would take about seven years. It’s been almost 23 years since the dedication of the piece and, to date, the last puzzle remains unbroken.

The first code breaker was a CIA employee who spent 400 hours of his own time working out the code with pencil and paper. He revealed his partial solution to a packed auditorium at Langley in February 1998. However, nothing was said outside of the CIA until sixteen months later when a Los Angeles based cryptanalyst announced he had broken the code using a Pentium computer and some custom software.

The first deciphered sequence was a poetic phrase composed by Sanborn: “Between subtle shading and the absence of light lies the nuance of iqlusion.” The misspelling was intentional and added as a method of introducing a degree of difficulty.

The second refers to an object that could be buried in the grounds at Langley and to a W.W. who knows the exact location. It is believed that W.W. refers to William Webster who was head of the CIA at the time of the commissioning of the piece and with whom Sanborn reportedly shared the secret of all four sequences.

The third sequence was a passage from Howard Carter’s account of the opening of the tomb of Tutankhamen in 1922. This passage also contains an intentional misspelling.

The fourth sequence remains unsolved. Sanborn and Scheidt intentionally made this sequence the most difficult to solve. They have hinted that it is not standard English and would require a second level of cryptanalysis. Misspellings and other anomalies in previous sections may help, but that is conjecture. Some suspect clues are in other parts of the installation: the Morse code, the compass rose or perhaps even the fountain. One thing is for certain, the final section only contains 97 characters which does not leave very much information to study for patterns. In any code, the longer the text, the easier it is to discern patterns and break the code.

In 1996 Sanborn discovered a typo in his sculpture. He had deleted an ‘x’ from the end of a line in section two (K-2) – a section that was already solved. The ‘x’ was supposed to signify a period or section-break at the end of a phrase. Sanborn had left it off for aesthetic purposes, he didn’t believe it would affect the way the puzzle was deciphered. It in fact did; however, the correction hasn’t seemed to help anyone with deciphering the final section.

In 2000 Sanborn revealed to the New York Times that the part of the sculpture that reads “nypvtt” becomes “Berlin” once it is decoded. With the release of this information the cipher world went to work. Clues abounded. When the work was being created the Berlin Wall was coming down and it is believed that Sanborn was aware that three sections of that wall were being given to the CIA as a gift from the German government. However, there is still no solution.

Sanborn states that other than what he has revealed only two of the 97 characters have been deciphered. He has created a website to assist those who are serious in their pursuit of a solution. One gains access to the website by revealing the first ten letters of the 97-letter puzzle.

To encryption enthusiasts Kryptos is the Everest of codes. However, the solving of the last cipher doesn’t necessarily end the hunt for the ultimate truth about Kryptos. Scheidt hints there may be more to the puzzle than what you see.

For a while Sanborn was impatient the cipher wasn't being solved. It was affecting his life in ways he hadn’t imagined with people trying to contact him regarding solutions. Although he insists there is definitely a solution, he would be just as happy if no one ever solved it. “In some ways, I’d rather die knowing it wasn’t cracked,” he says. “Once an artwork loses its mystery, it’s lost a lot.”